He told a Kent State classmate he was ‘scared’ of the unrest. Two days later, he was dead.

By Paula Schleis For the Akron Beacon Journal

April 29, 2020

APRIL 29, 1970: VIETNAM WAR WIDENS TO CAMBODIA

Editor’s note: This seven-part series relives the days leading up to the May 4, 1970, shootings at Kent State University, through the lives of some of those most affected. Today, the events of Wednesday, April 29, 1970, and the life of sophomore William “Bill” Schroeder.

Now this was how college life was supposed to be, Bill Schroeder told his sister, Nancy.

In a letter that traveled a week earlier from his room at Kent State University to hers at the University of Kansas, he wrote of how he’d been spending the spring quarter learning photography with a borrowed camera, attending evening lectures, going to concerts and joining general “bull sessions” around campus.

It was rare that the sophomore didn’t have a job consuming his spare time. From his days as a newspaper carrier through his time in food service, he’d always been a worker. The previous summer, he’d made enough on the assembly line at the Ford Motor plant in Lorain to buy himself the 1969 Fiat he had his eye on.

But he cleared his plate for the spring. A season that was already a gift for its unseasonably warm weather, it offered Schroeder a chance to immerse himself in university life for the first time since transferring to Kent State in the fall from the Colorado School of Mines.

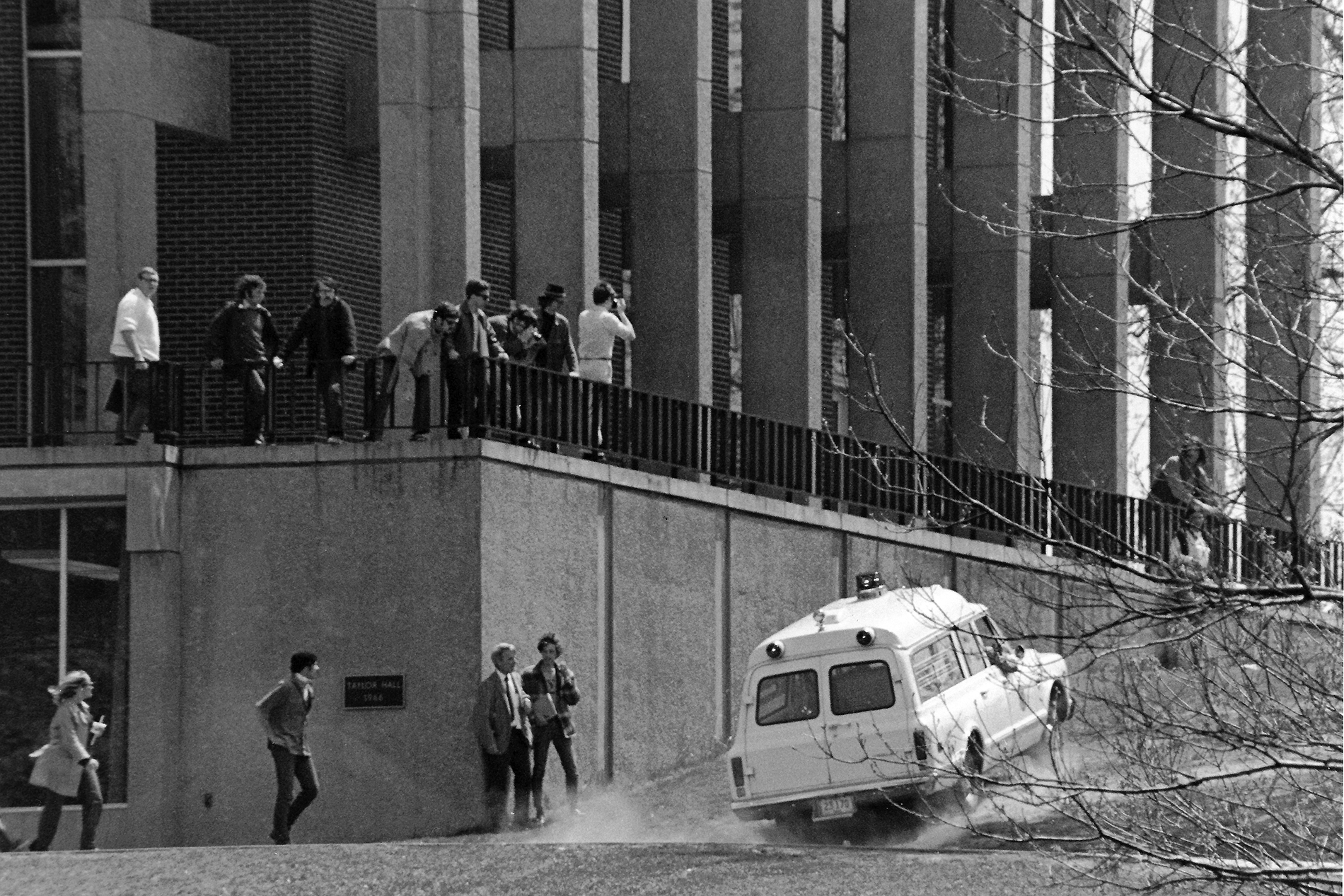

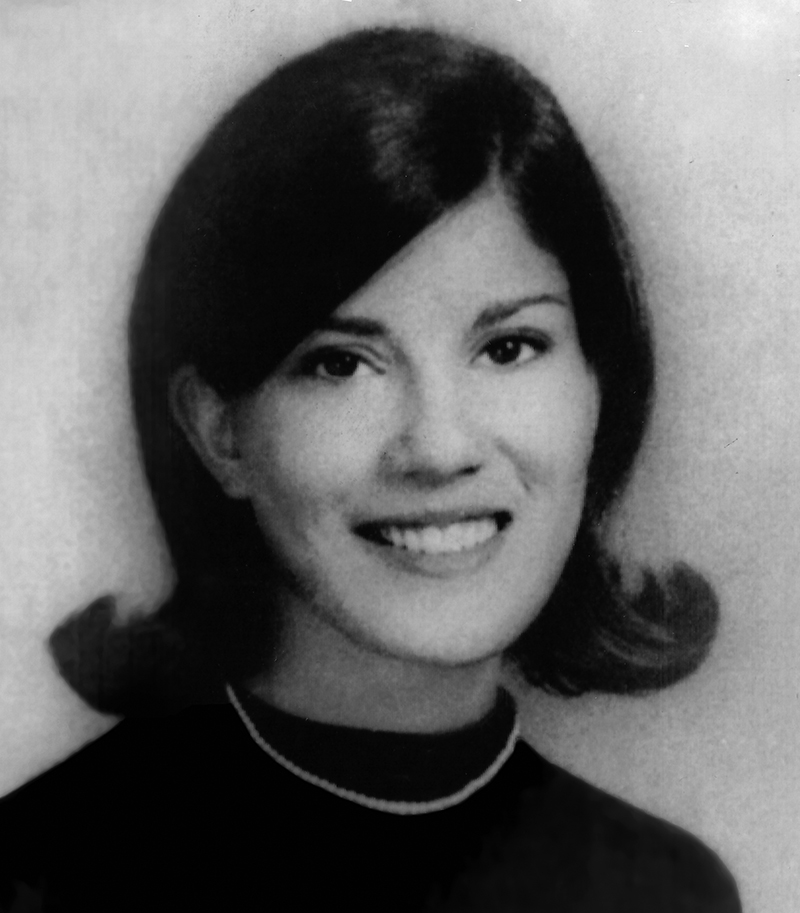

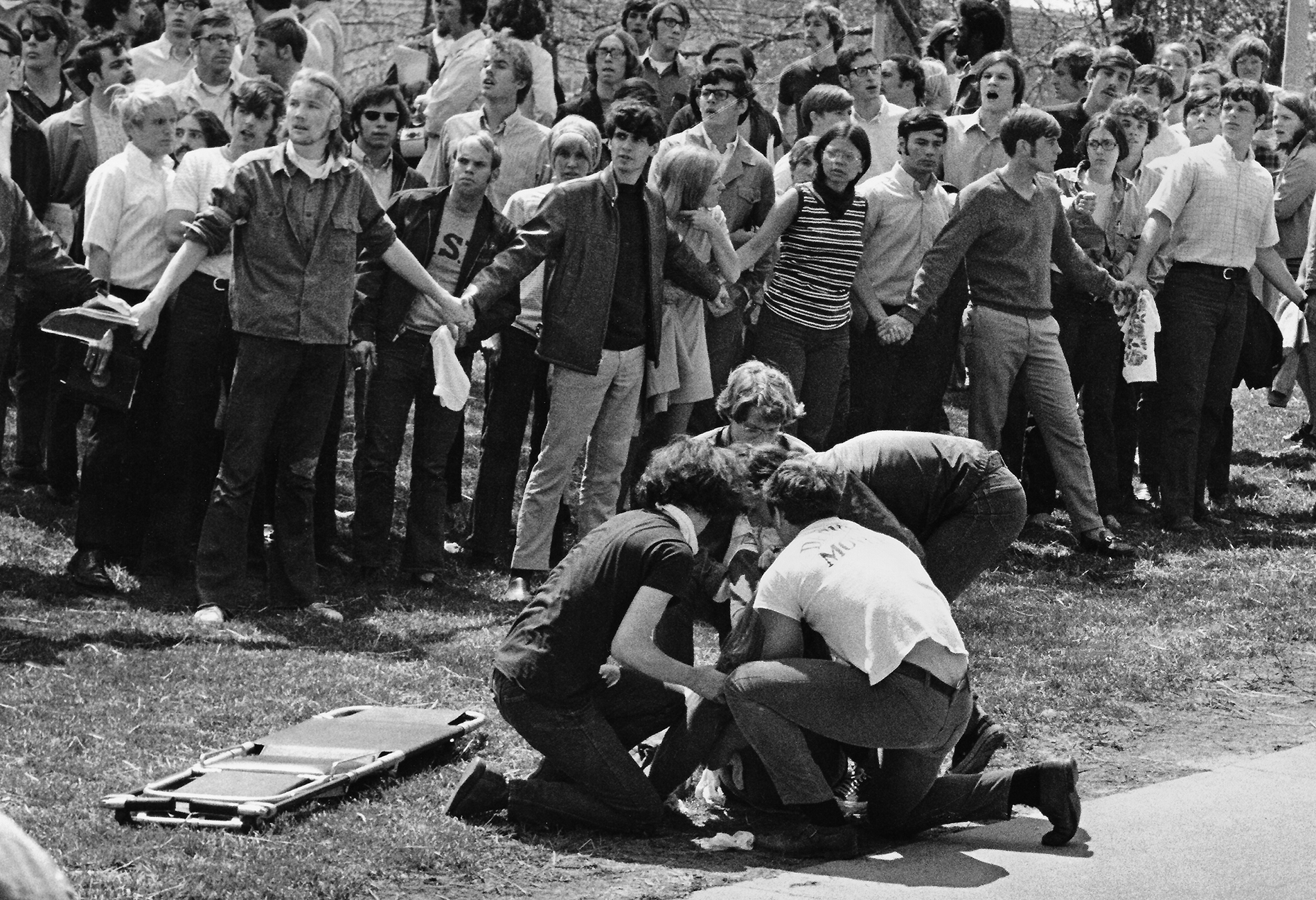

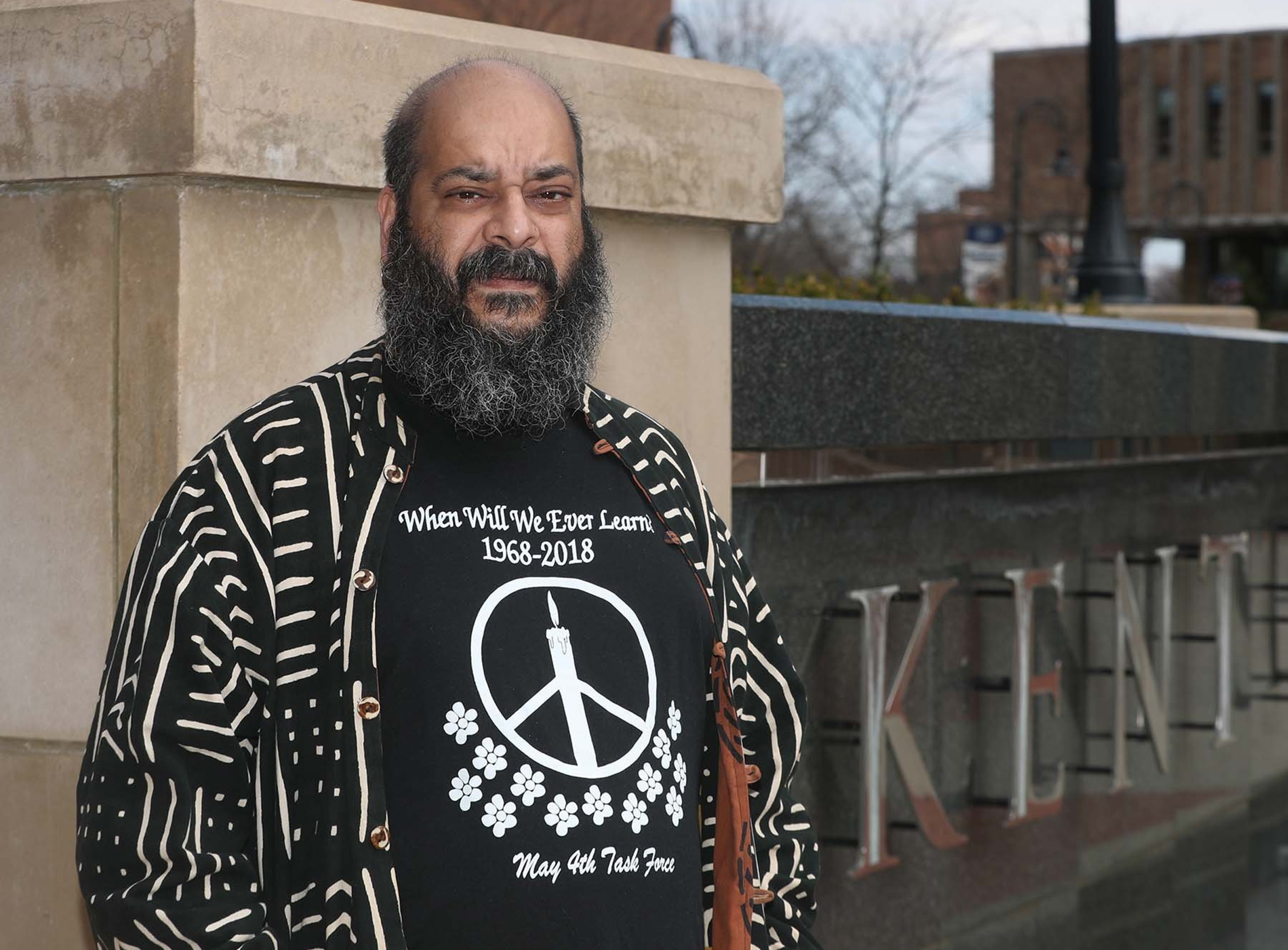

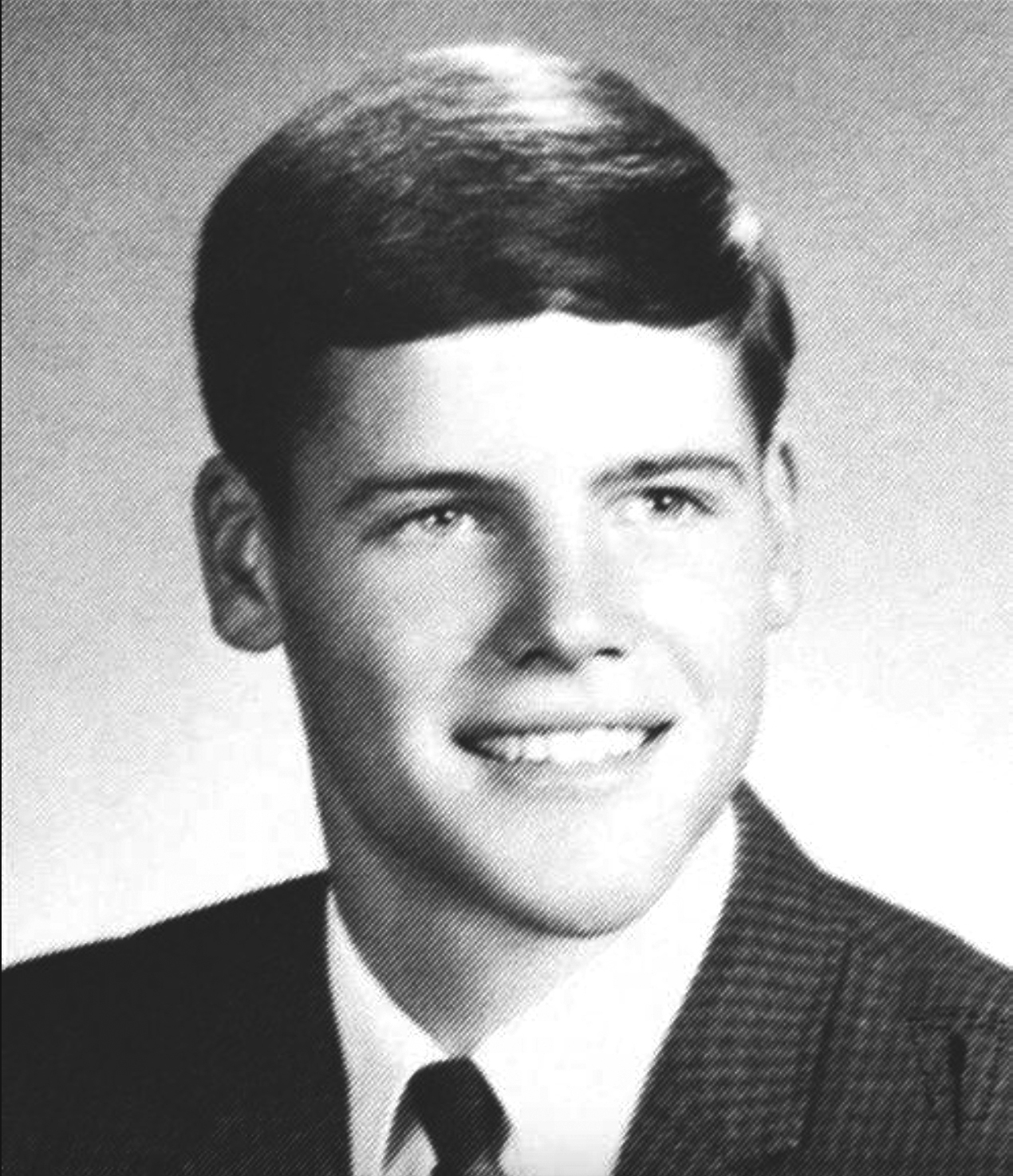

William “Bill” Schroeder was one of four students killed at Kent State University on May 4, 1970.

The newspaper headlines the morning of April 29, 1970, however, threatened to end his fun and leisurely exploration of the campus.

“GI, Arms Sent into Cambodia,” the Akron Beacon Journal front page announced in the afternoon edition.

The news was a punch to the gut to many who thought the United States was trying to find a way out of the Vietnam War. President Richard Nixon had campaigned on such a promise, and, indeed, some 200,000 U.S. troops had been brought home in the past year.

What did this unexpected escalation mean?

Bill had never been a protester during the long, contentious years of the conflict. Still, he wanted to understand it. He abhorred the loss of life and property that came with war, and like most 19-year-olds, he needed to know why his peers were being sent to the front lines.

After all, there was a good chance he’d be joining them if the war continued.

Perhaps he could understand it better from the inside. His senior year in high school, he applied for, and received, a full four-year Army ROTC scholarship.

At the age of 17, he committed his life for the next 10 years. Four at college, with tuition paid and a $50 monthly stipend. Four more after that on active duty. Two more after that in the Army reserve.

Bill threw himself into ROTC the way he embraced every new interest.

This was the kid who joined the Cub Scouts, and went on to earn the rank of Eagle by the age of 13. Who picked up the cornet, and made it to the All City Band. Who dribbled a basketball, and worked his way to varsity captain at Lorain High School.

When he graduated in 1968, he ranked 22nd in a class of 453.

And so it was with ROTC. Most grading periods, he was ranked first in his military class. He earned the Academic Achievement Award, and was given the “award for excellence in history” from the Association of the United States Army.

How he loved studying history. His parents, Florence and Louis Schroeder, watched that interest grow over their son’s lifetime.

Arguably, it began with his fascination with Tonto, the Lone Ranger’s television sidekick, which led to a thirst for information about Indian history. His family quenched it with trips to museums, parks and historical sites.

During such a trip to Fort Ancient near Lebanon, Ohio, he found an actual arrowhead, which made him wonder what other treasures the ground might hold. He bought a geologist’s pick and started collecting fossils and rock samples.

That’s how he ended up at the Colorado School of Mines. But when the school dropped its geology program, Bill decided to move closer to home and turn his psychology minor into a major.

Trained psychologists were as important to the military as soldiers and chaplains, he told his family.

In his search to understand the causes and effects of war, Bill read extensively. First about the Indian wars, then working his way through the Civil War, the world wars, the Korean War and, of course, Vietnam.

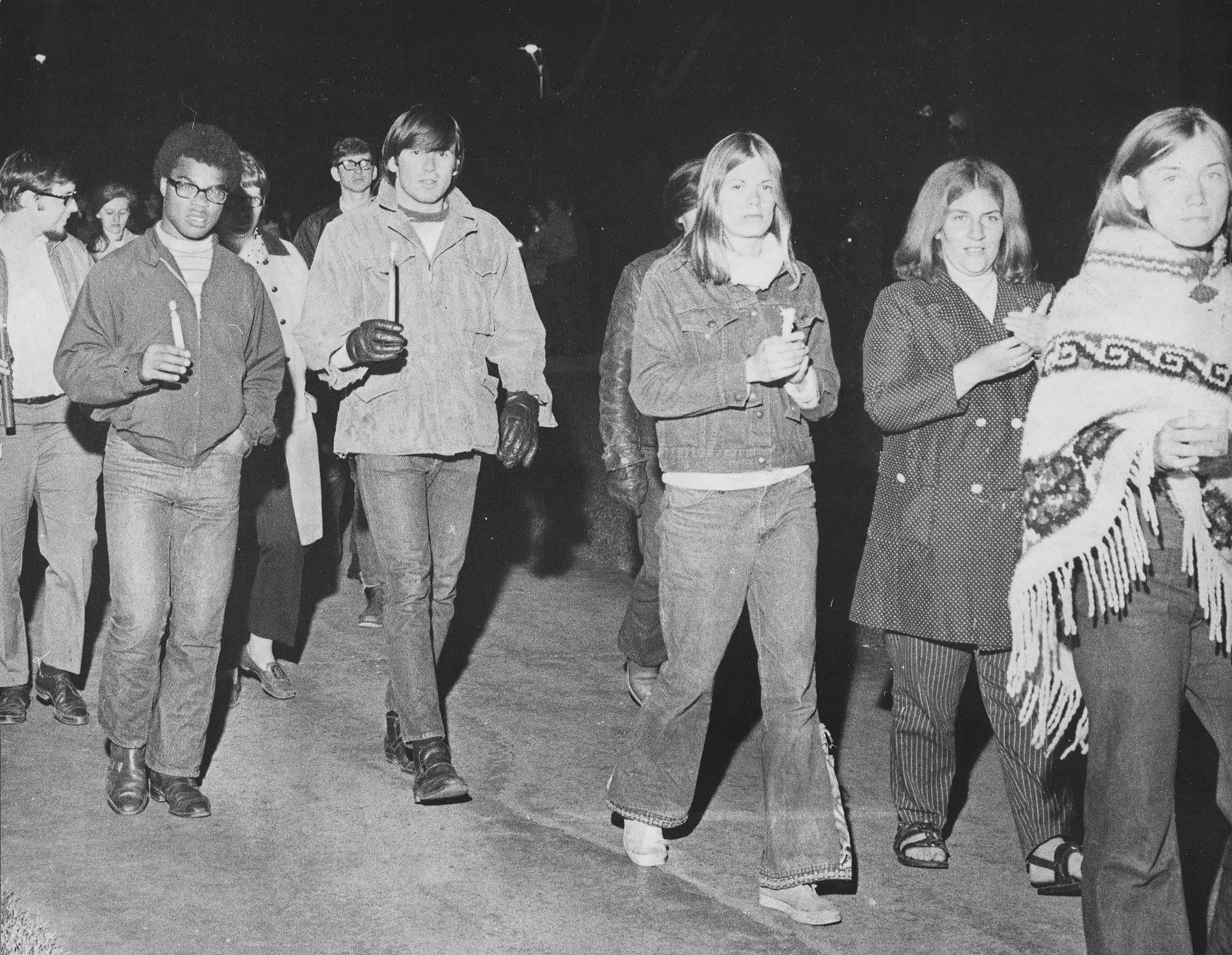

Sociology professor Jerry Lewis (left) points the way for Lou and Florence Schroeder, parents of slain Kent State student William Schroeder, during the annual candlelight vigil march on May 4, 1978. At right is Glenn Olds, the university president. Ted Walls | Akron Beacon Journal

He read other works, from Sigmund Freud to Ray Bradbury, and wondered if he might even write one day. He’d love to travel and share his experiences, the way Ernest Hemingway and James Michener did.

Oh, how he loved to travel. When he decided to leave Colorado, his swan song to the West was a trip to the Grand Canyon and other sites around Arizona and New Mexico.

He once went to Guaymas, Mexico, with three strangers he met through bulletin board ads – a Brazilian missionary and two conscientious objectors doing service in the medical ward of an Army hospital. He came back changed by experiencing life in the impoverished community.

His last trip in December was to Florida, where he offered to help clear rocks and shrubs in preparation for the Miami Rock Festival. But he was disturbed seeing the way the local “flower children” lived on the beach, and the way police treated them. After two days, he decided he’d rather spend the rest of his Christmas holiday with the people he loved, and returned home.

That’s where he was the past weekend. Home. Discussing how he had a new hero, theologian and philosopher Albert Schweitzer. It was a pleasant two days.

Now just one final push to end the school year.

William Schroeder’s parents, Florence and Louis, file past the plaque bearing their son’s name near the new May 4 Memorial at Kent State, May 4, 1990. Susan Kirkman Zake | Akron Beacon Journal

The past year had been a peaceful one at Kent State, not at all like the previous spring when dozens of students had been arrested in various demonstrations and marches.

As a matter of fact, this very day the last four of the students involved in those disturbances were released from jail. Chapter closed.

The April 29, 1970, front page of the Kent Stater wasn’t about war in Southeast Asia. It was about a mud fight outside the Tri-Towers dorm, and the hopes of students for more rain to make more mud.

In three days, as military helicopters hover over the campus and search lights shine into their window, Bill will tell his roommate, “I’m scared, Louie.”

In four days, he’ll call his parents to reassure them he wasn’t participating in any of the unrest, and that he was upset that demonstrators had burned the ROTC building.

In five days, he’ll be dead.

Sources: MAYDAY: Kent State (1981) by J. Gregory Payne; a biography written by Bill’s parents, Florence and Louis Schroeder, to aid lawyers in civil cases; Akron Beacon Journal; The Kent Stater; The Lorain Journal.