How the Kent State shootings divided a city and changed it forever

By Bob Gaetjens and Diane Smith, Record-Courier

May 1, 2020

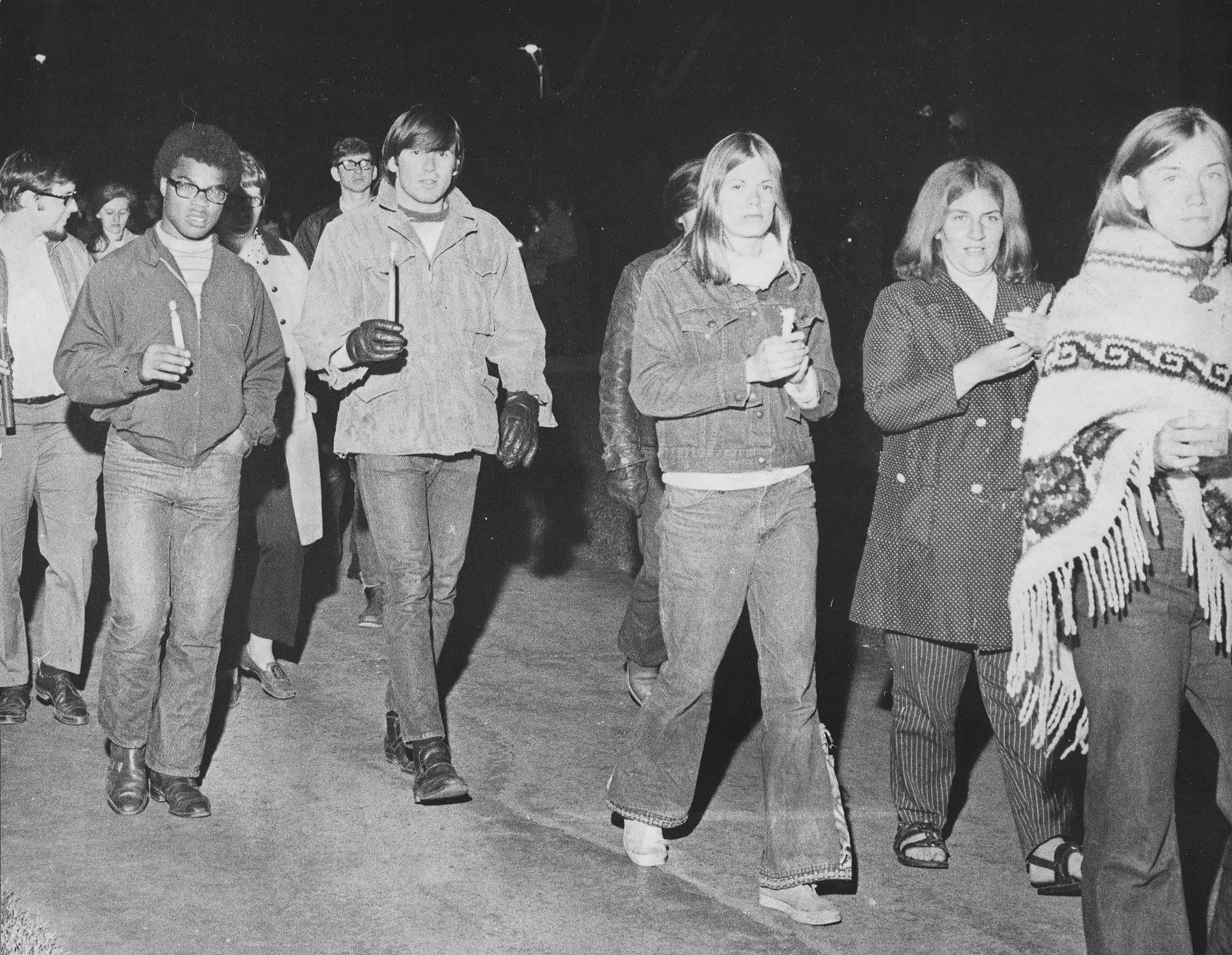

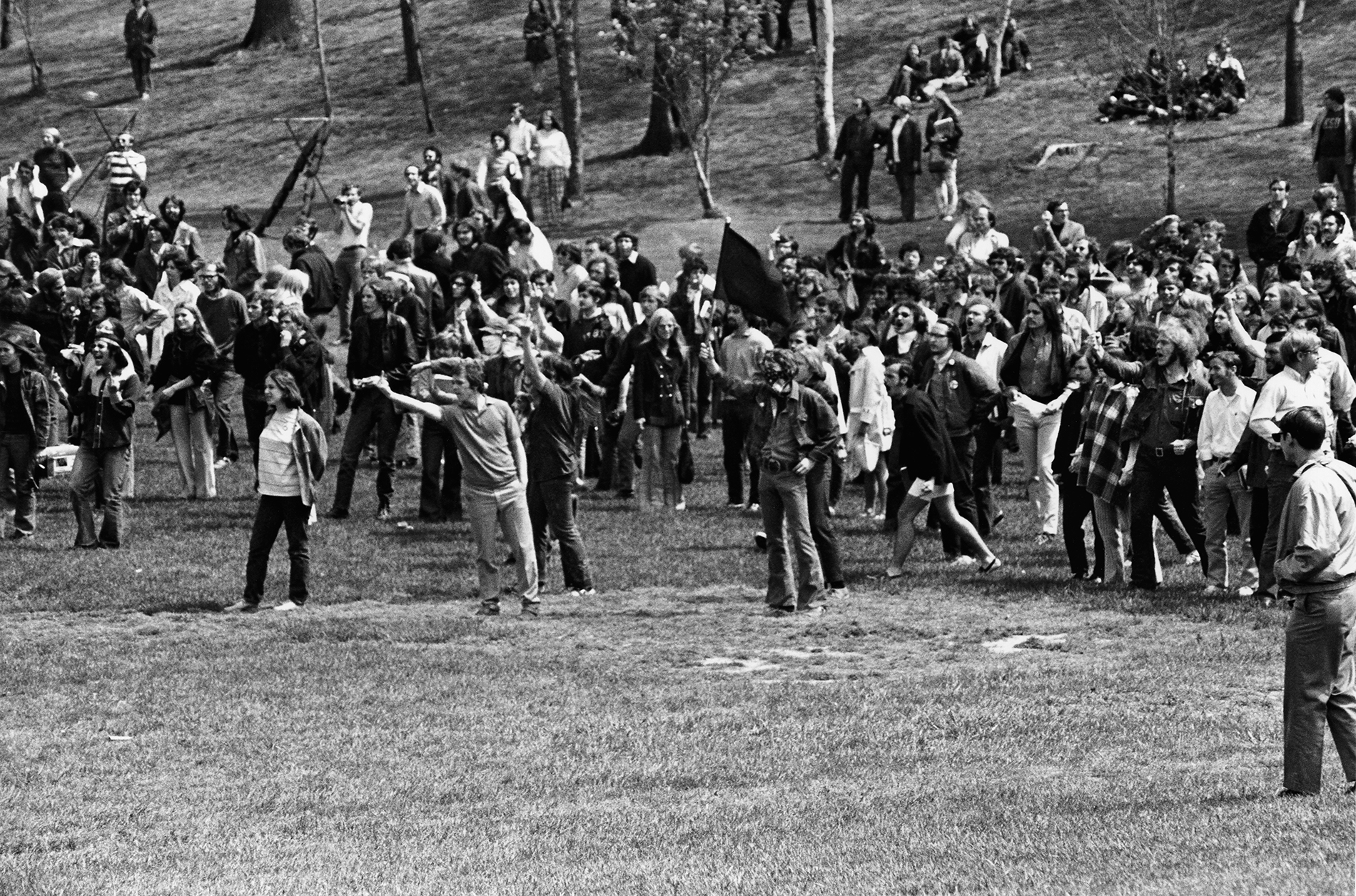

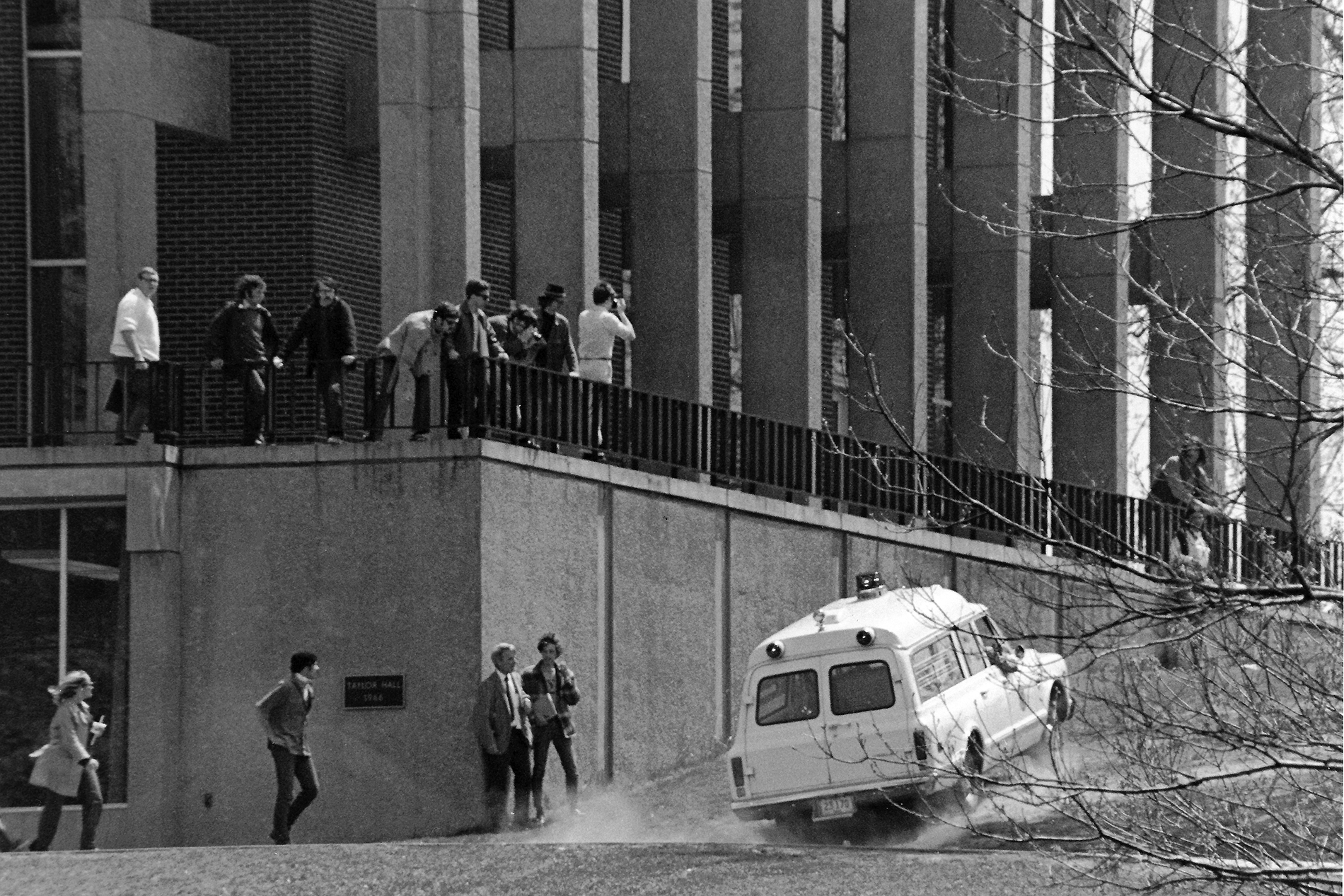

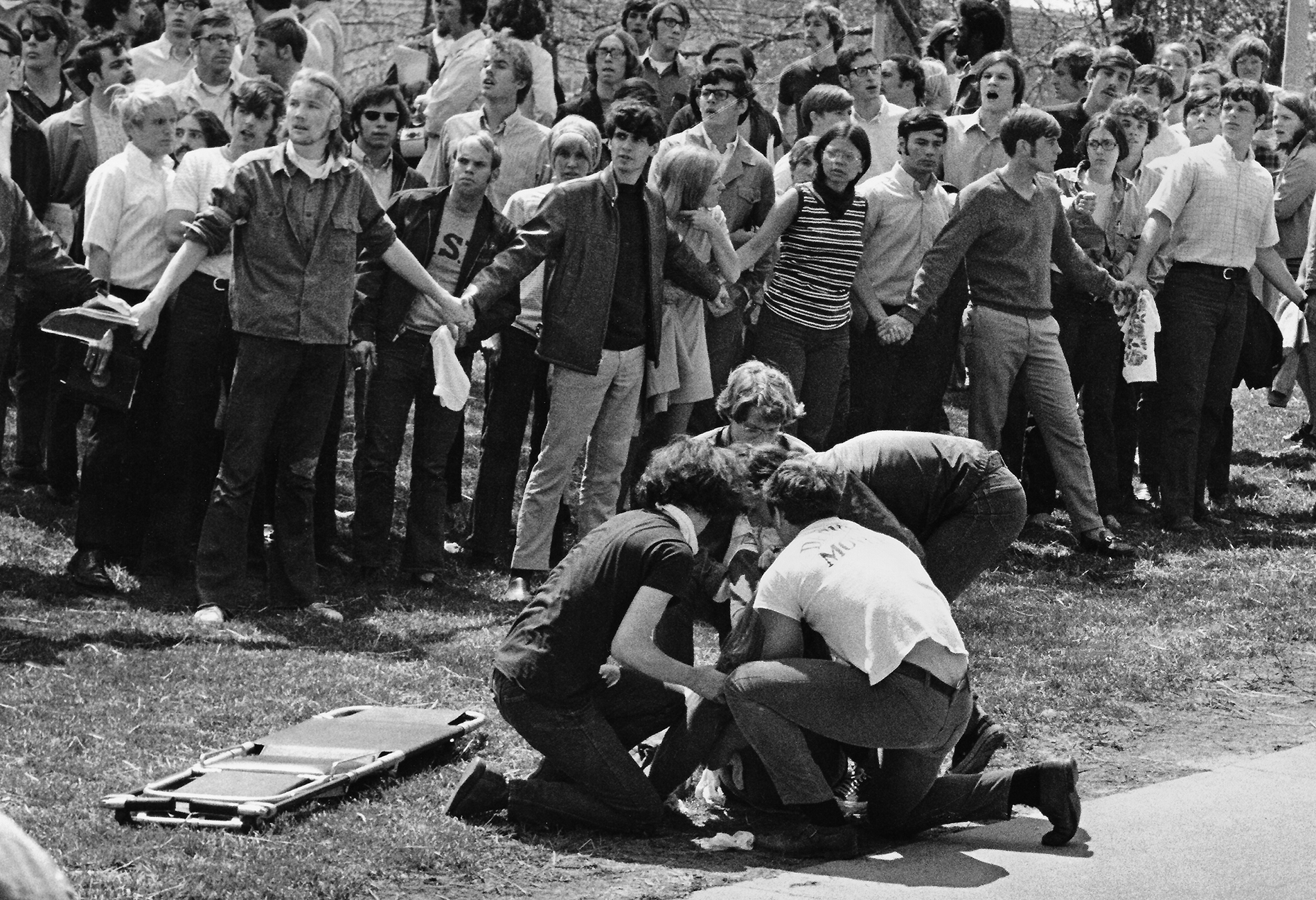

The May 4, 1970, Kent State shootings shaped the city of Kent for decades to come.

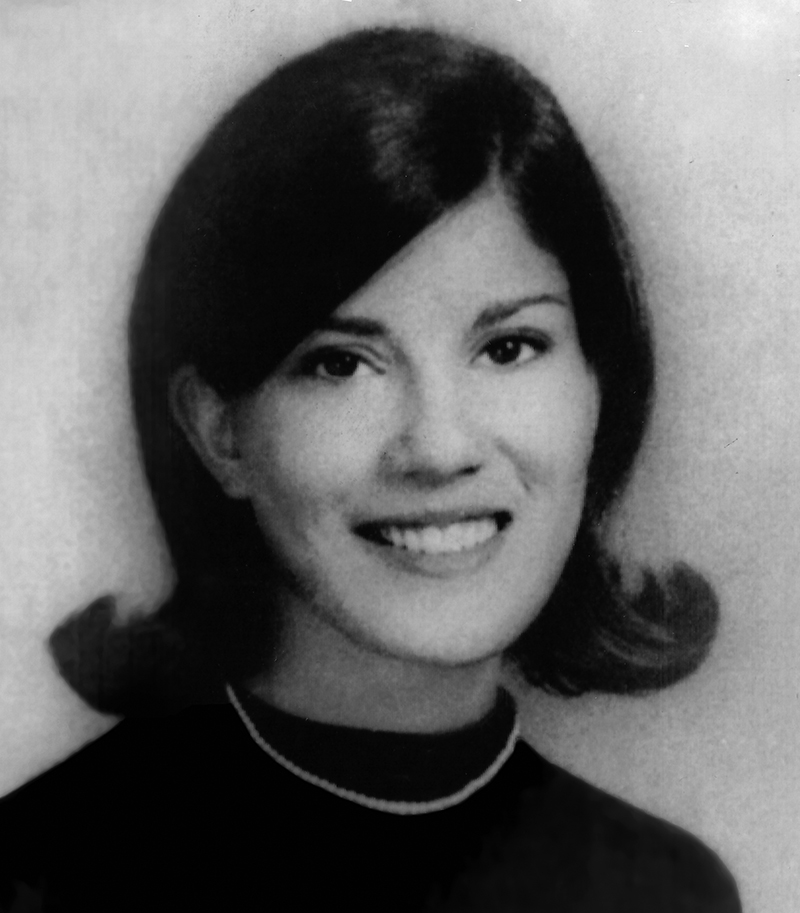

In the immediate aftermath of the shootings – which claimed the lives of Allison Krause, Jeffrey Miller, Sandra Scheuer and William Schroeder – most people in the city supported either the students or the National Guard. Those two perspectives shaped the city’s politics.

“Opinion sort of got galvanized right away and stayed there for a long time,” said Laura Davis, a freshman at Kent State at the time of the shootings who now serves as director of the May 4 Visitors Center. “That divide still exists to a certain extent.”

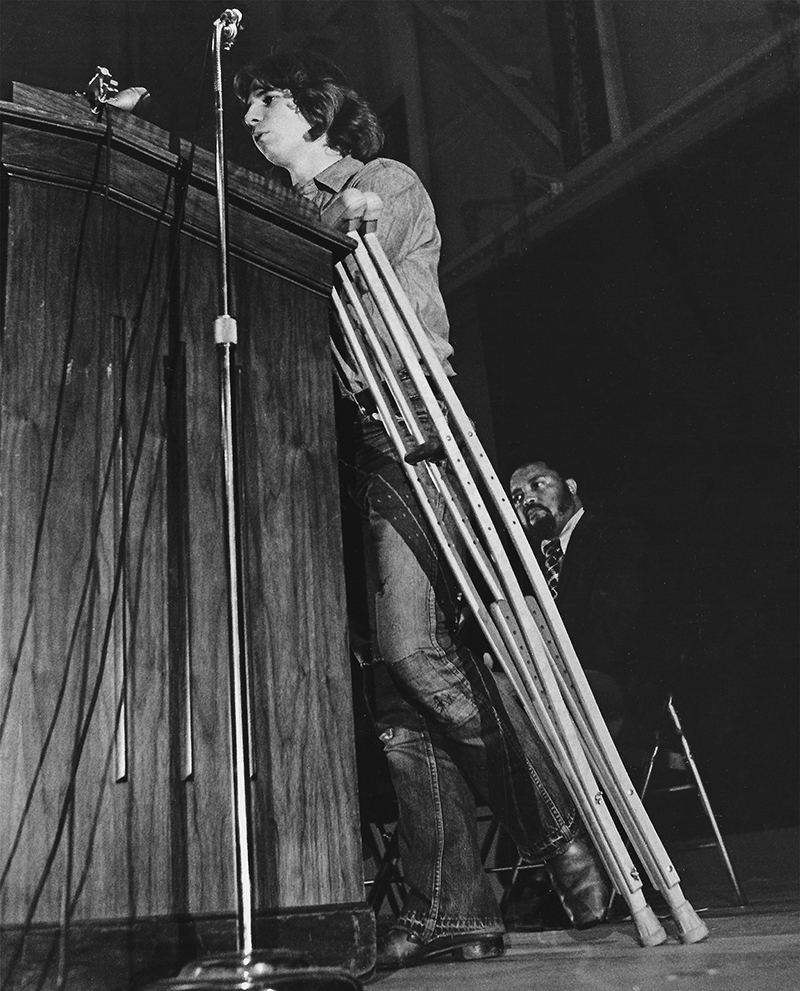

It can be seen in the polarizing reaction to KSU’s invitation to Jane Fonda to speak at this year’s 50th anniversary of the shootings. Fonda also spoke at the university during the 1974 memorial ceremony, along with ex-Marine Ron Kovic, whose story was shared in the movie “Born on the Fourth of July.”

The public commemoration, and Fonda’s speech, were canceled this year, but not because of controversy. Instead, the coronavirus outbreak canceled in-person classes, as well as public events such as the commemoration.

Sleepy town erupts

Kent was a railroad town for years. Before Haymaker Parkway was built, it was impossible to drive through town without being delayed by a train. The last passenger train went through town in 1970.

That sleepy railroad town erupted in 1970 — along with much of the country — on April 30, when President Richard Nixon widened the Vietnam War by invading Cambodia.

Roger DiPaolo, who served for several decades as the editor of the Record-Courier, was attending high school in Kent that spring and remembers that time.

“May 4 was the perfect storm,” said DiPaolo, Kent Historical Society’s historian in residence. “You had a city that was not equipped in any way to deal with any unrest. You had a volunteer fire department in the 1970s; you had a police chief who was well-intentioned but more equipped to handle a much smaller town.”

May 4 was the perfect storm. You had a city that was not equipped in any way to deal with any unrest. You had a volunteer fire department in the 1970s; you had a police chief who was well-intentioned but more equipped to handle a much smaller town.

During the 1970s, the campus was beset with anti-war protests. There also were protests over the location of the planned gym annex in 1977, an issue DiPaolo covered as a reporter for the Record-Courier. The annex eventually was built on part of the ground where the May 4 shootings happened.

Current Mayor Jerry Fiala said the city had a “dark cloud” hanging overhead the week of the shootings.

“It was a scary time for everybody,” he said. “It was a shame that it happened, but we learned from it.”

Doria Daniels, who has lived in Kent’s south end all her life, said she was aware of the restrictions Kent was under that May. But in the south end, life was pretty normal.

“Our businesses stayed open,” she said. “The dry cleaner was still open. My mother’s beauty shop was open. A lot of the businesses downtown closed and didn’t come back.”

During the time of martial law, she said, residents were urged to stay in their homes, just as they have been during the coronavirus pandemic. Daniels said she organized activities for the youth to keep them off the streets and out of trouble.

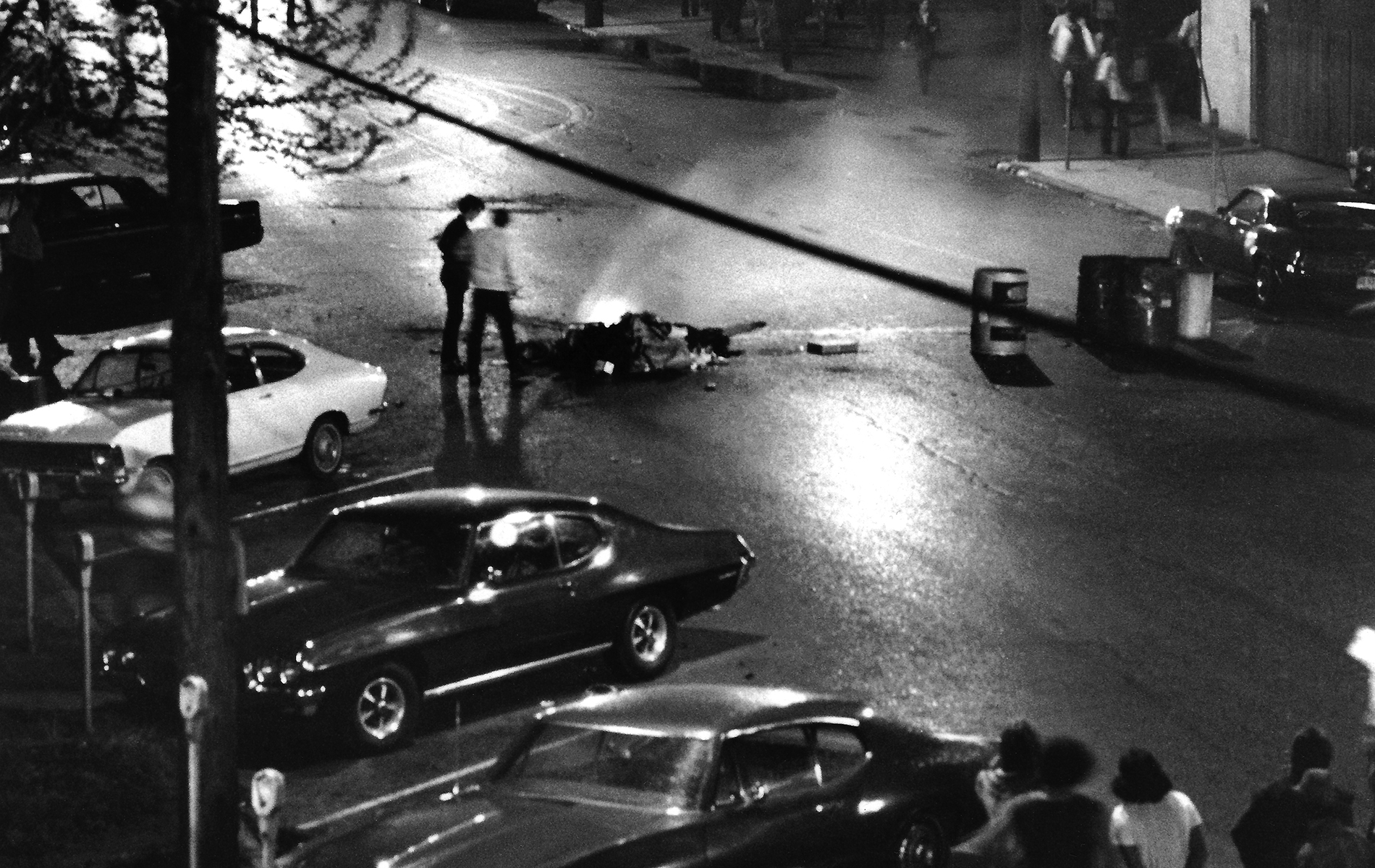

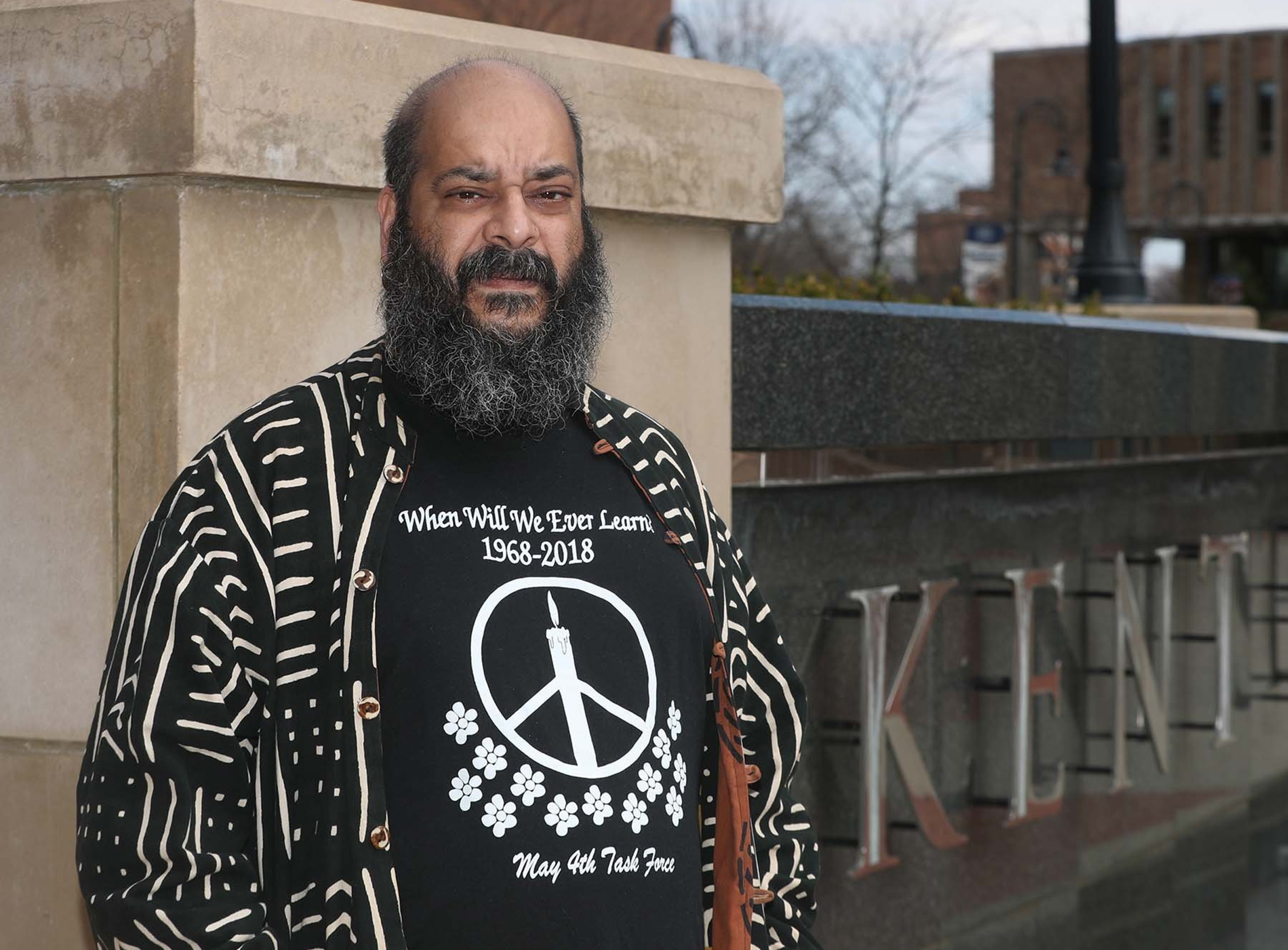

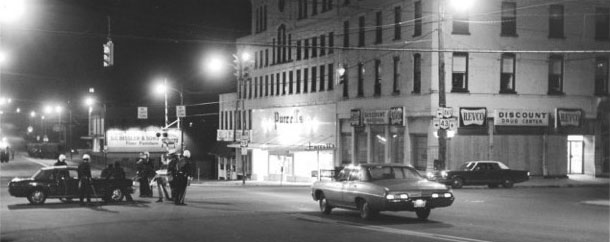

Police officers make a traffic stop May 2, 1970, on the night that protesters burned down the Kent State ROTC Building. File photo | Record-Courier

“Our neighborhood is very close knit,” she said. “We stayed tight.”

Jim Myers, an owner of Thompson’s Drugstore in downtown Kent, said a picture window in his store was broken by a protester. But Myers had faced that problem before and had a board handy to secure the window.

Myers, who was president of the Board of Education, was more concerned about a May 5 school bond issue. With the town being under martial law, he didn’t know if people would even be permitted to cast ballots. But voters approved a bond issue, which resulted in additions to Theodore Roosevelt High School still used to this day.

“It was probably our finest hour,” he said.

Exodus

After the events of May 1970, Kent saw an exodus of residents and businesses, sparked by people who no longer felt safe in the once sleepy, railroad town.

The population nearly doubled between the years of 1950 and 1970, with 12,500 residents in 1950 and 28,000 two decades later, said Sandra Halem, Historical Society president emeritus. But many larger companies left town after 1970, and single-family homes were converted to student housing, fast food restaurants and gas stations.

Many of the buildings on Main Street are still recognizable today, although some of the businesses — like Hickman’s Jewelry — have closed since the 1960s when this photo was taken. (Submitted photo)

DiPaolo said the university also experienced a falloff in enrollment in the years following the shooting, which hampered its growth.

“All those dorms built in the 1970s, they were basically vacant,” he said. “One was turned into an office building.”

Following the shootings, he said Kent State University made a “strategic decision” to focus away from downtown, creating “two separate entities” — the city of Kent and the university.

The downtown area also experienced a serious fire at the current site of Hometown Plaza a few years after the shooting.

“Nobody was able to do anything to recover from it,” he said. “The city didn’t have any will to do anything. There was a 40-year period of stagnation.”

Polarized

Citizen attitudes toward the shooting were sharply polarized during much of the 35 years from 1970 until the redevelopment of downtown, said Davis.

“The students were blamed; the victims were blamed,” she said. “You couldn’t talk with people about it without knowing it was OK to do so.”

Halem and her husband, Henry, moved to Kent in 1969 when he got a job at KSU teaching glassblowing at the school of art.

On May 4, Halem was teaching at Garfield High School in Akron when she heard about the shootings. She was the only member of the teaching staff who lived in Kent.

I didn’t even know if I could come home. I drove home and there was a helicopter flying overhead and no one was on the streets. I knew Henry was planning to go to a demonstration on campus, and I didn’t even know if he was alive until he got home. It was very terrifying.

“I didn’t even know if I could come home,” said Halem. “I drove home and there was a helicopter flying overhead and no one was on the streets. I knew Henry was planning to go to a demonstration on campus, and I didn’t even know if he was alive until he got home. It was very terrifying.”

After the shootings, the Halems found themselves at a town and gown meeting. There, she told Loris Troyer, then-editor of the Record-Courier, that they were giving serious thought to moving out of Kent.

“I remember so clearly him saying to me, ‘Absolutely not. You need to stay. This town needs good people to stay here and work,’ ” she said.

So, the Halems took action, joining the city’s bicentennial committee and Historical Society. She ended up taking a job at KSU as a speechwriter for former President Carol Cartwright.

Healing

Davis said that kind of community involvement and engagement, which she connected to the formation of Main Street Kent, was a helpful catalyst for redeveloping downtown and redefining the community from one that looked to its past to one that looked to the future.

“I saw a generational change in terms of the people who were participating in Main Street Kent,” she said.

Halem said she gained a new appreciation for how much KSU students needed the city, and how much the city needed the students.

They have needed each other to survive. The students come here, not just because of the academics, but because it’s a great place to be. I think it’s important that people see it as a success. People who now come to Kent, it’s a destination now. We have music, live entertainment, many food choices.

“They have needed each other to survive,” she said. “The students come here, not just because of the academics, but because it’s a great place to be. I think it’s important that people see it as a success. People who now come to Kent, it’s a destination now. We have music, live entertainment, many food choices.”

Time and healing had begun in earnest by the 2000s, Davis said. When Lester Lefton took over as president of Kent State, that healing began to take place in public as discussion around creating a link between downtown and the campus began.

“The community building, the bridge building metaphorically, went on for quite a few years and then became more visible when President Lefton got here,” said Davis.

By then, she said the people on the committees running the organizations like Main Street Kent had undergone a generational change.

Downtown Kent has changed considerably since students protested the Vietnam War five decades ago. A new block of commerical and residential space, hotel and public parking garage is near Main Street, shown here. Kevin Graff | Record-Courier

Kent State President Lester Lefton delivers opening remarks on Oct. 4, 2013, as the Lester Lefton Esplanade opened to connect downtown Kent with campus. Lisa Scalfaro | Record-Courier

“They were really thinking about who they were,” said Davis. “It did coincide with a generational change, but I think it’s very interesting that it wasn’t just that the generations turned over; it was the generation taking over taking on the task of saying, ‘This is who we are.’ ”

That planning manifested itself in a unique partnership among the university, the city and private interests that ultimately led to the Esplanade connecting the city and university and reconstruction of commercial blocks of downtown, ushering in new clientele to both businesses and the university.

The Kent State University Foundation built a hotel and conference center downtown at the end of the Esplanade, while the university constructed its new architecture building on adjacent land within view of downtown. The city has since built a new police station nearby along the Haymaker Parkway corridor.

Fiala points to the redevelopment in downtown Kent as evidence of the city’s healing.

“I don’t think it would have happened if we hadn’t healed,” Fiala said.

Reporter Bob Gaetjens can be reached at 330-541-9440, bgaetjens@recordpub.com or @bobgaetjens_rpc.

Reporter Diane Smith can be reached at 330-298-1139 or dsmith@recordpub.com.