Kent State Shootings: Warning, flames greeted National Guard at campus

By Paula Schleis for the Akron Beacon Journal

May 2, 2020

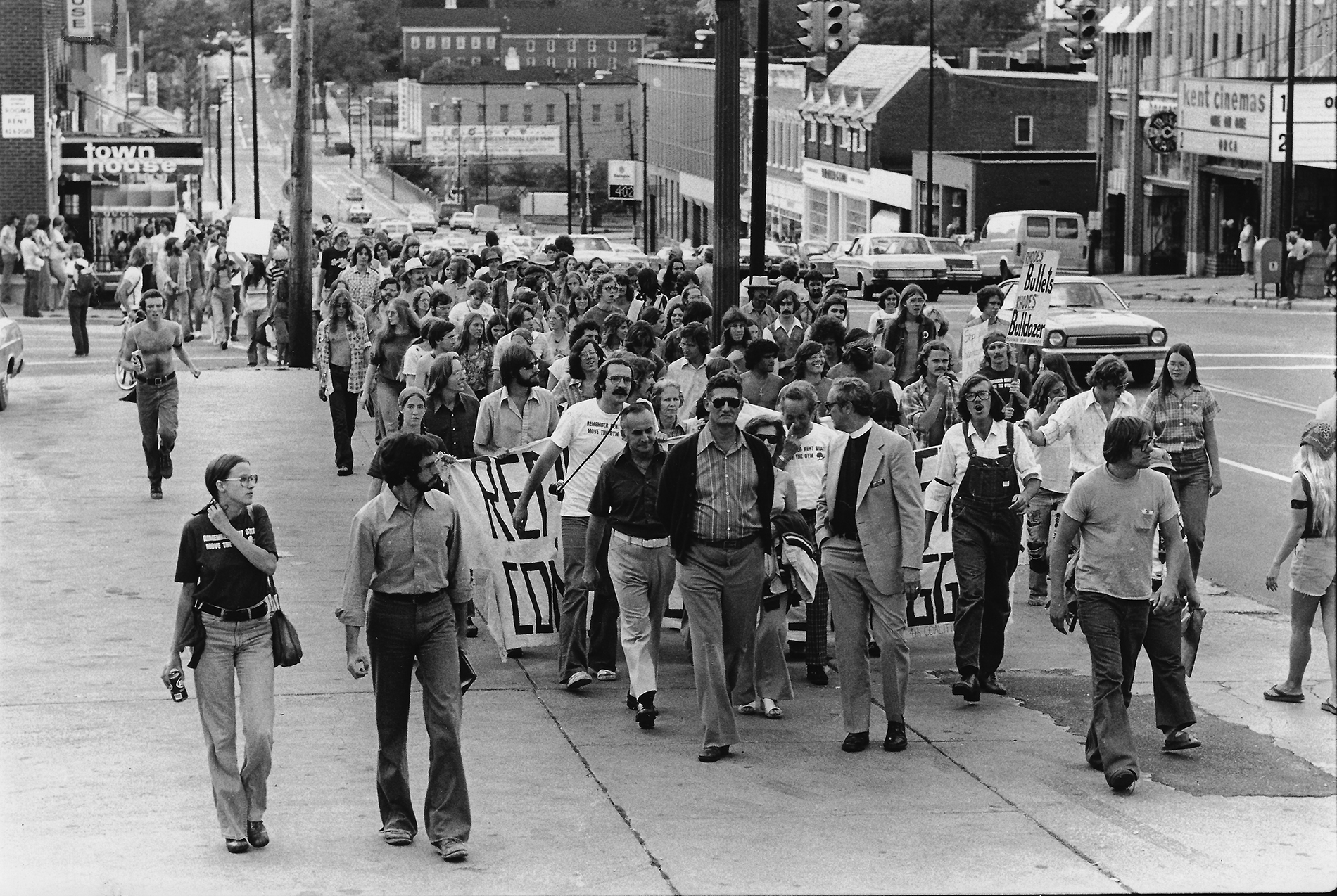

MAY 2, 1970: KSU ROTC TORCHED; GUARD ARRIVES

Editor’s note: This seven-part series relives the days leading up to the May 4, 1970, shootings at Kent State University, through the lives of some of those most affected. Today, the events of Saturday, May 2, 1970, and the life of Ohio Army National Guard commander J. Ronald Snyder.

The horizon was glowing red as a convoy of Ohio Army National Guard trucks and jeeps crowned a hill, headed for Kent State.

It was just after 10 p.m. that Saturday night, and Capt. J. Ronald Snyder knew he wasn’t looking at the afterglow of a setting sun.

The thing turning the overcast sky into a crimson canvas could only be fire.

Snyder, the 34-year-old commander of Company C of the 145th Infantry, had not been told what to expect when he’d been directed to Kent State.

He knew things on the campus of Kent State University had been tense, but in 14 years with the National Guard, he’d never been called to a campus. When he thought of college kids, he pictured sit-ins, chanting and sign-holding. Not fire in the sky.

This ominous feeling as if he were headed to the front lines of a battle was even more strange because he wasn’t far from home. He lived next door, in Stow.

Snyder was actually born in Ravenswood, West Virginia, where he received a one-room-schoolhouse education through the sixth grade.

At the age of 12, his family moved to Akron, part of a migration of thousands of people who came to the area to take jobs in the city’s rubber factories and related businesses.

He finished his education at Akron’s South High School, then continued his family’s legacy of military service. An ancestor served at Valley Forge during the Revolutionary War. Relatives fought in the Civil War. His father served in World War II.

National Guardsmen stand in relief as flames from the Reserve Officer Training Corps building at Kent State University rise into the night sky May 2, 1970. The guard arrived on campus earlier that evening after the mayor of Kent, LeRoy Satrom, declared a state of emergency. Don Roese | Akron Beacon Journal

There was no war in 1956 when Snyder came of age, but the National Guard gave him the ability to serve his country part time while pursuing another career. His day job was an investigator for the Summit County Coroner’s office.

Before turning 30, Snyder had risen from the ranks of private to captain, and given command of Company C of the 145th Infantry, some 180 men.

Company C – they called it “Charlie Company” – was a quick-response team, whose members had to be ready to go in less than two hours of receiving an assignment.

Such a call had come just a few days earlier when Charlie Company had been ordered to deal with a Teamsters’ strike in nearby Richfield. Union members were attempting to stop freight deliveries. Snyder’s men provided security for non-union trucks traveling the turnpike.

Then, just like that, his men had been ordered to drop the strike assignment and go to Kent State.

The first call came in at 1 p.m., relayed to Snyder by radio.

“Be ye prepared,” the radio operator, who liked to use biblical language, told him dramatically. The mayor of Kent was anticipating trouble beyond what his small police force could handle. Charlie company should be ready to turn on a dime, if needed.

Snyder was glad for the warning. He’d sent half of his men home to spend the Saturday afternoon with their families. He’d need time to get them back.

Kent Mayor LeRoy Satrom had good reason to be concerned. Students had torn up downtown the previous night, breaking windows, starting bonfires. The city’s 22-man police force donned riot gear and spent three hours forcing the mob back to the campus.

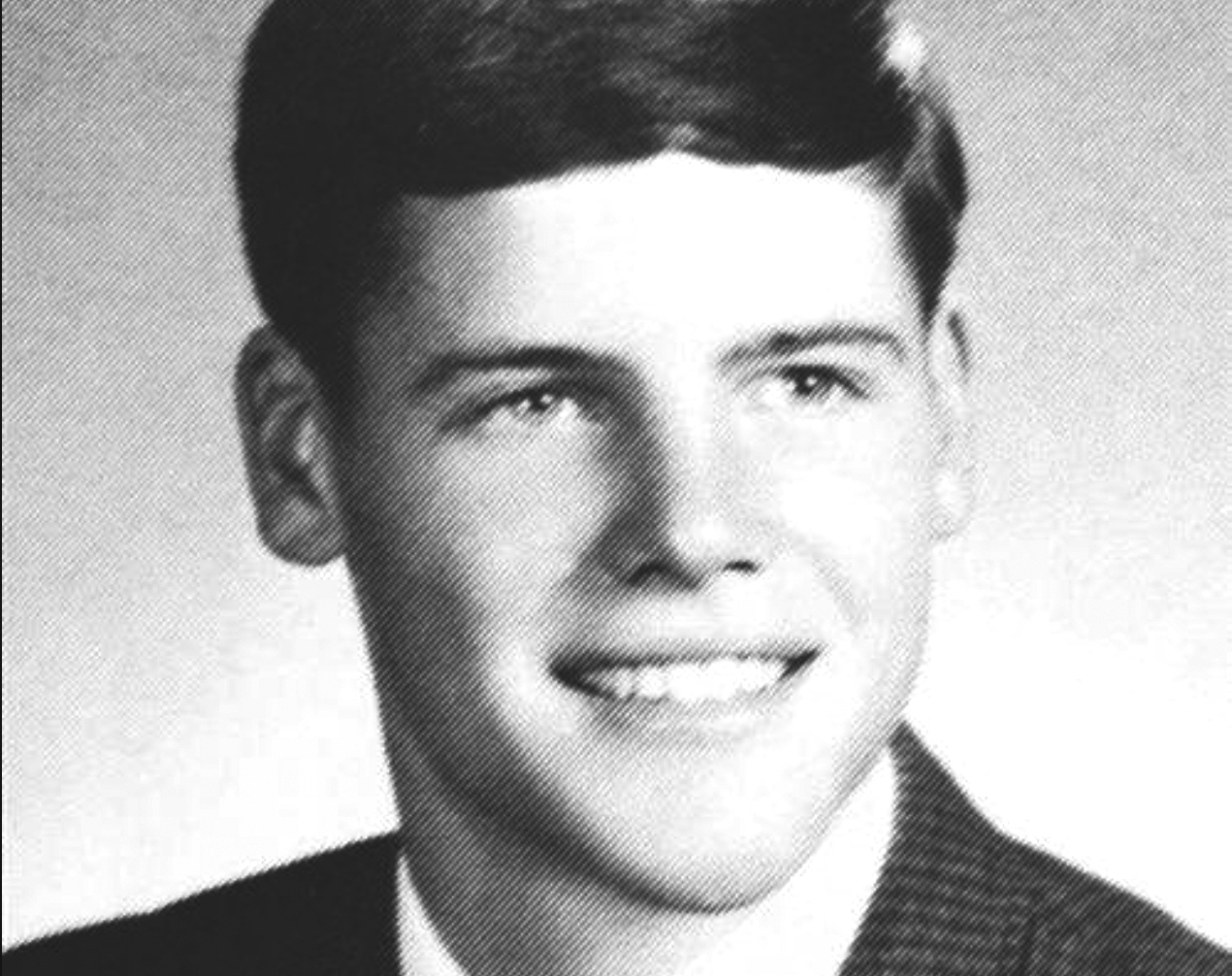

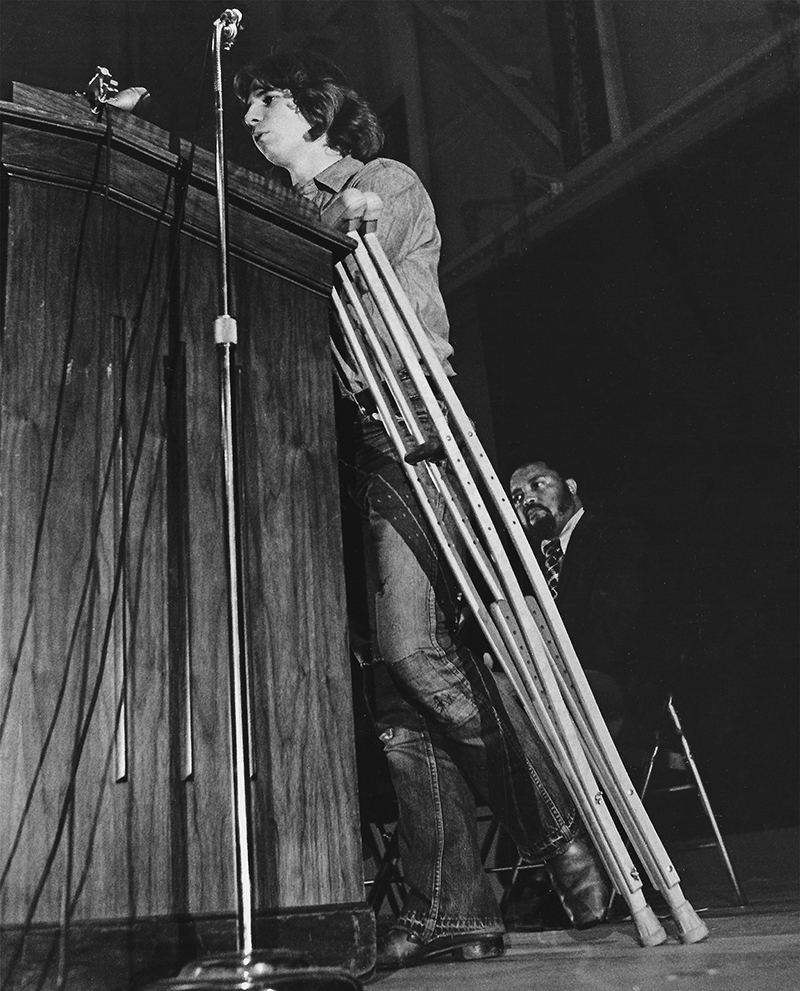

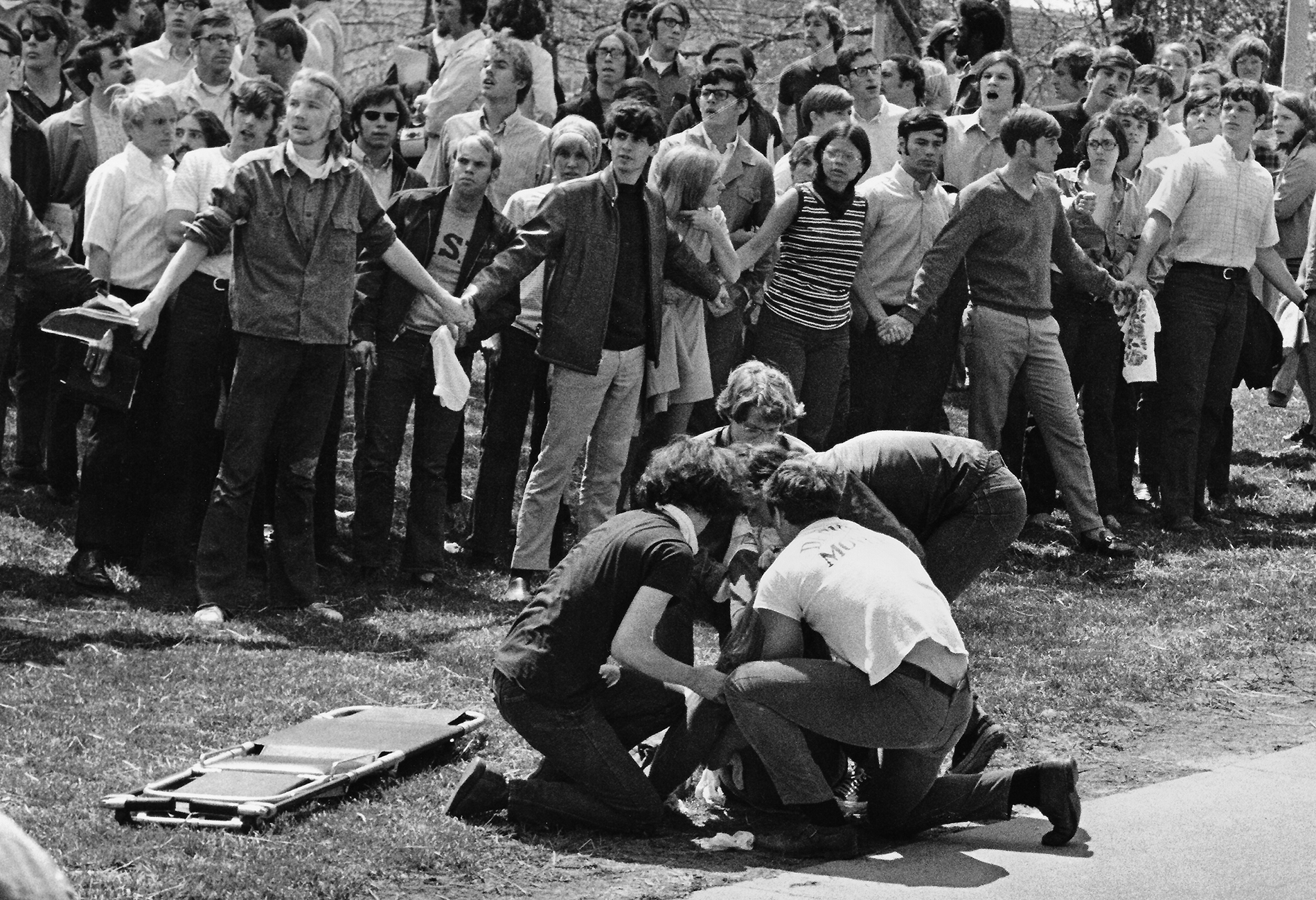

Captain J. Ronald Snyder, right, who later lied about finding a gun on the body of Jeffrey Miller on May 4, 1970 at Kent State. The story was intended to bolster a contention that guardsmen had fired at the students in self defense. Bill Hunter | Akron Beacon Journal

Business owners woke Saturday morning, surveyed the damage and debated over whether to replace the glass or just board the openings in anticipation of more trouble.

Gawkers drove in from all over the region, clogging the streets. Fatigued officers were called in for traffic duty.

There was no way city police could handle another event like that. And as the day progressed, Mayor Satrom was increasingly certain another bad night was coming.

He imposed a dusk-to-dawn curfew on the city, ordered bars to remain closed, and banned the sale of all alcohol. But the police chief said it wouldn’t be enough. Informants had told him radical revolutionaries had arrived on campus with more destructive plans in mind, including burning the old ROTC building on the campus Commons.

The National Guard told Satrom if he wanted them in town that night, he had to request it by 5:30 p.m. At 5:27 p.m., Satrom picked up the phone and called Columbus.

University officials, who had hoped to deal with any insurrections without the Guard, were not told the Guard was coming.

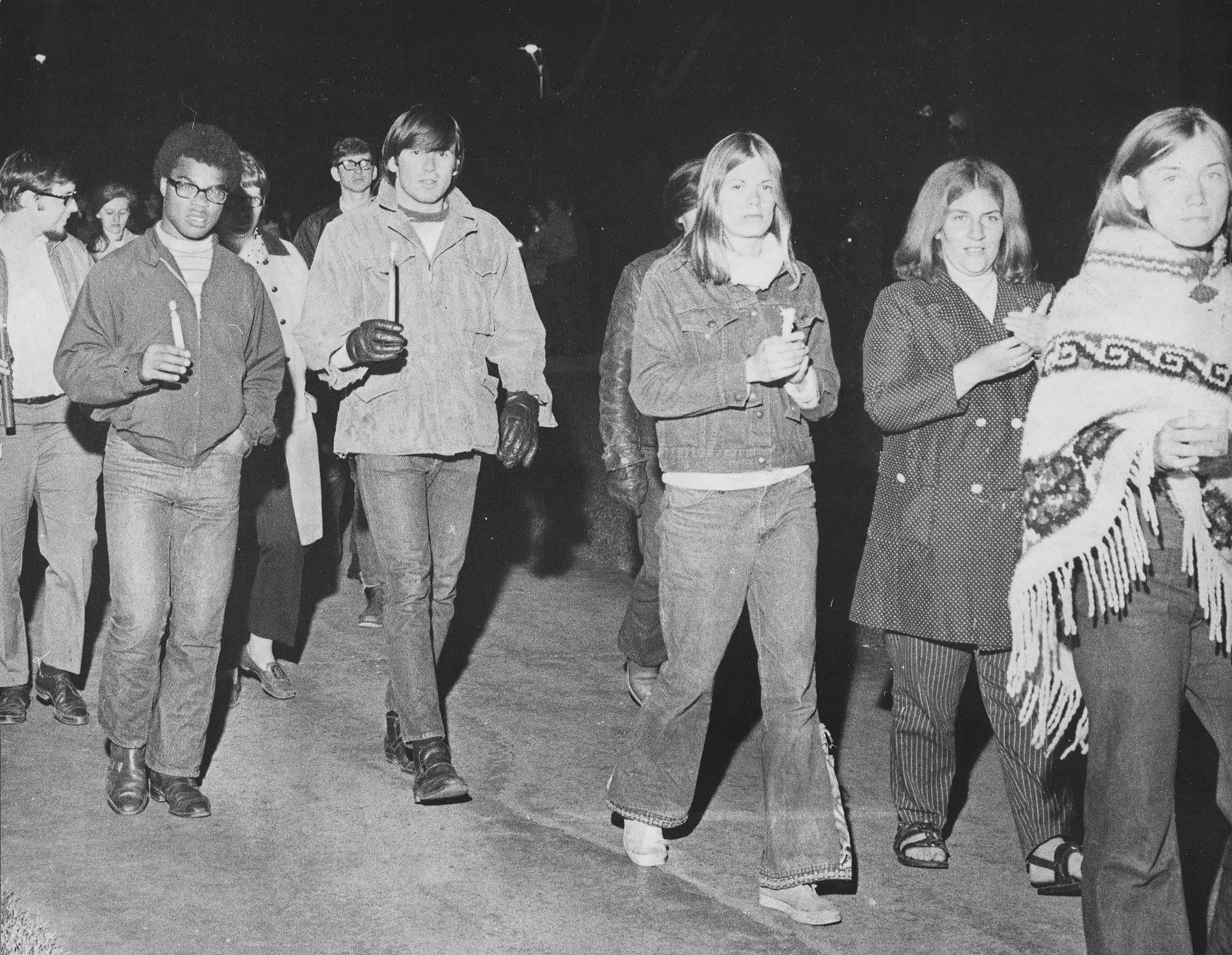

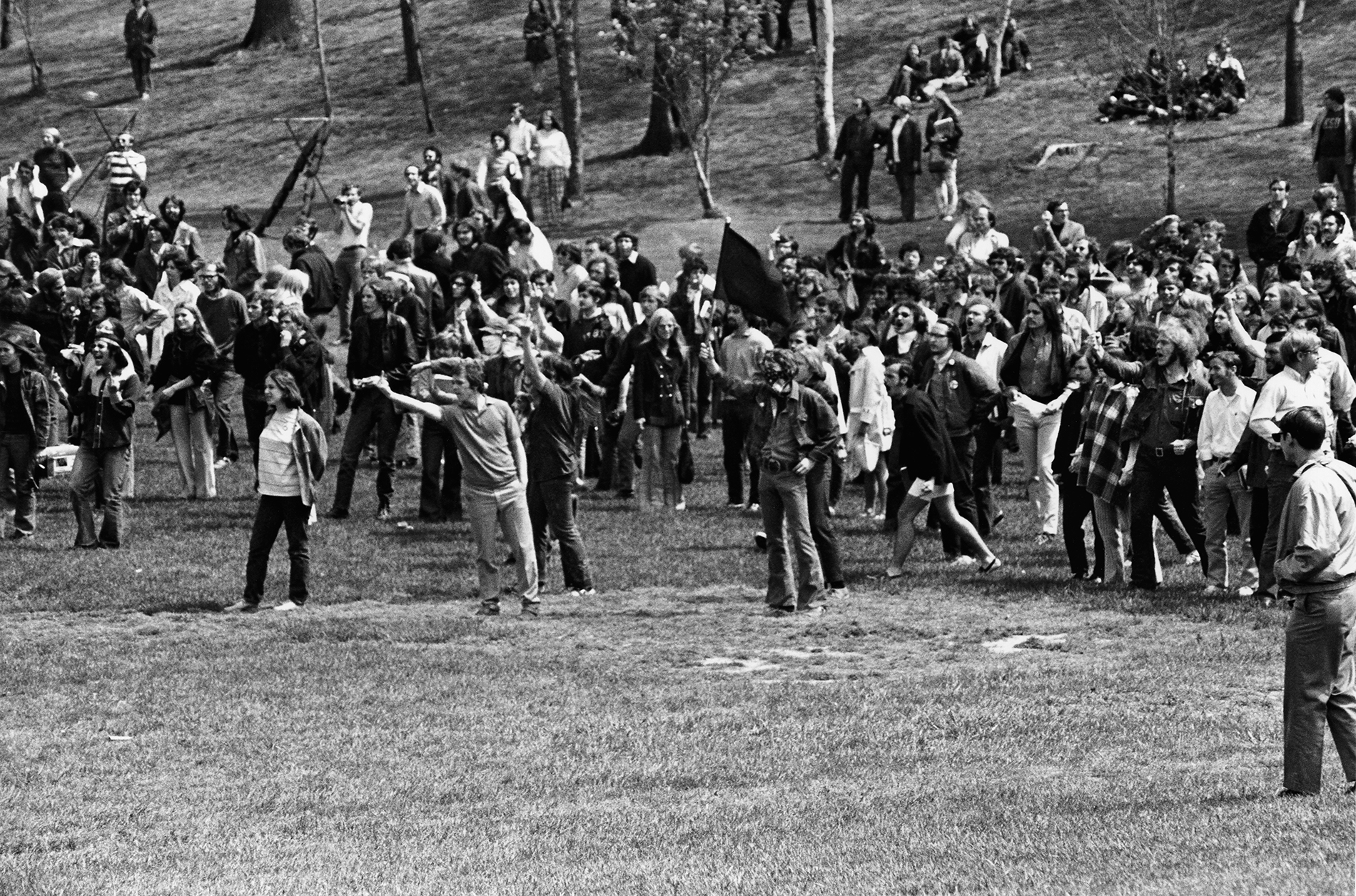

The trouble started simmering around 7 p.m. A few hundred students gathered at the Commons to hear speeches and chant anti-war slogans. The rally turned into a march, growing in size as it passed by the dormitories.

More than a thousand people had joined in by the time the demonstrators reached the ROTC building. It was an old rickety wooden World War II barracks used for some storage while awaiting a date with a wrecking ball.

But the building was a symbol. Around the country, anti-war protesters had been demanding an end to ROTC presence on university campuses.

At Kent State, after the demonstrators surrounded the building, several people made repeated attempts to set the structure on fire, each effort failing.

KSU President Robert White was out of town, so Vice President Robert Mason followed the playbook for campus emergencies. He put out the call for aid, with the Portage County Sheriff’s Office and Ohio State Patrol responding.

With riot batons at the ready, police wearing gas masks stand in front of the burning ROTC building at Kent State during a night of unrest on May 2, 1970. Paul Tople | Akron Beacon Journal

When the university called Kent police, the city shot back with the same answer that KSU police had given them the night before when they asked for help with the downtown riot: They were too busy protecting their own.

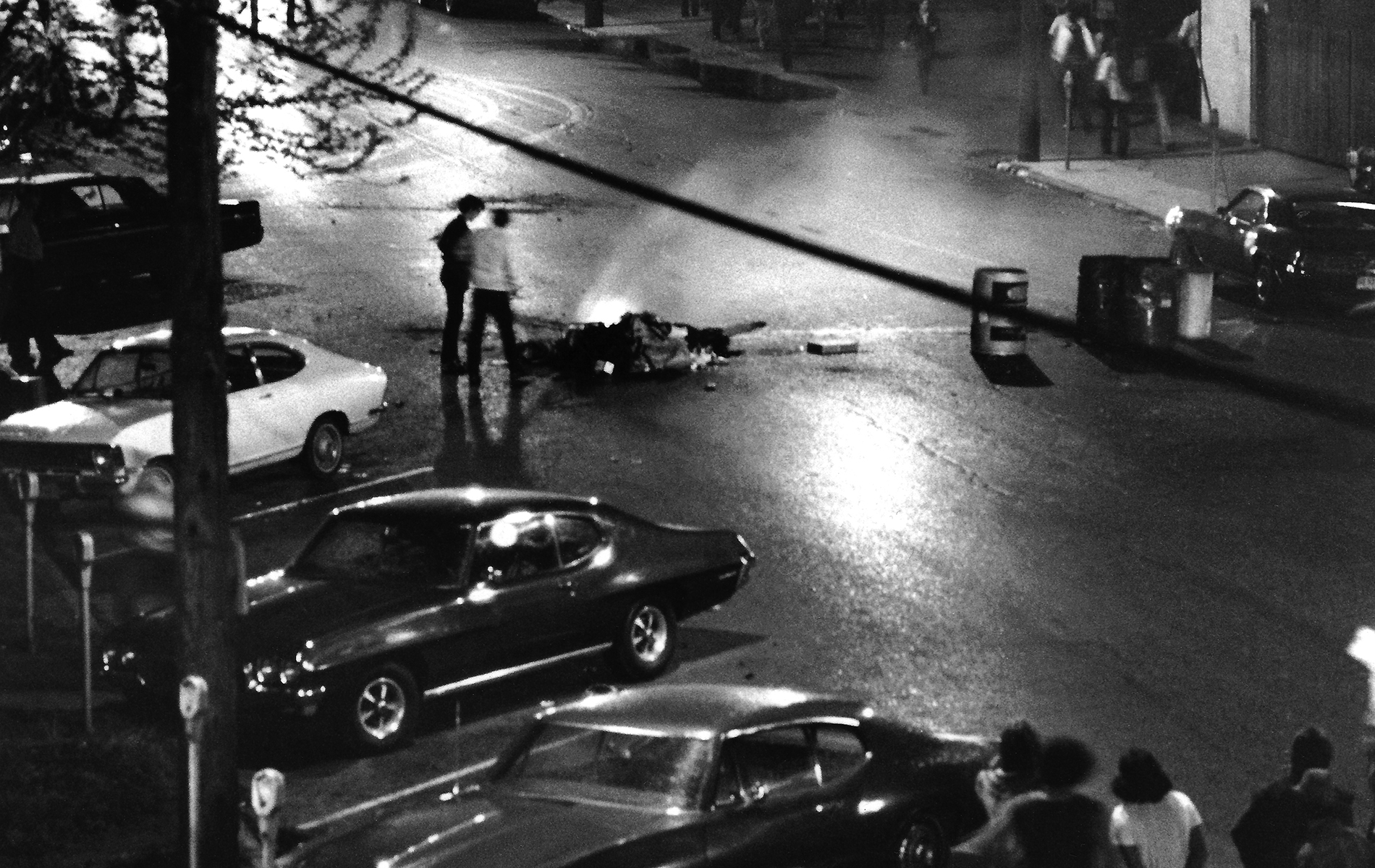

Finally, the persistent demonstrators were able to catch the ROTC building on fire. Kent firefighters arrived to put it out, without a police escort, but not unprepared. They had always seen the ROTC building as a likely target of arsonists.

What they didn’t count on was the reaction of the mob. They were pelted with rocks, and their hoses were cut with pocket knives or wrested away from them by angry protesters. The firefighters retreated.

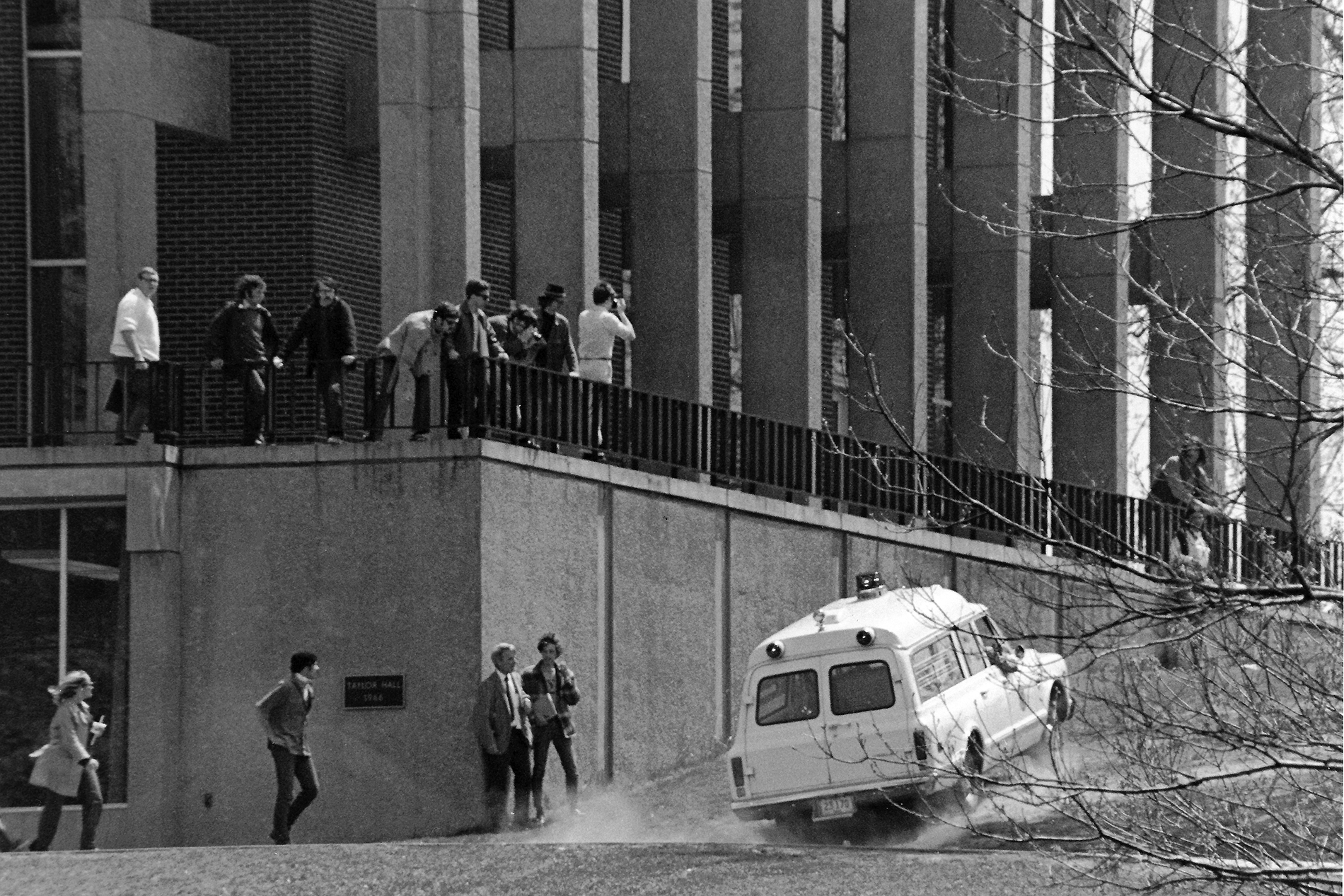

It wasn’t until 9:14 p.m. when Vice President Mason heard for the first time, on the radio, that the National Guard was on the road headed for Kent State.

The Guard pulled into town less than an hour later to find the ROTC building engulfed. The guardsmen tried to disperse the crowd, lobbing tear gas and pursuing the students with drawn bayonets.

National Guardsmen stand in relief against the burning ROTC building at Kent State University on May 2, 1970. The building was a total loss and was the worst damage from a night of student protests that swept the area. Don Roese | Akron Beacon Journal

The Kent State ROTC building lies in ruins May 3, 1970, after it was set fire the previous night. Paul Tople | Akron Beacon Journal

The battle was well underway by the time Snyder and his Charlie Company arrived.

Snyder’s orders were to seal off the university, stop people from outside the campus trying to join the movement inside; stop students from inside the campus from leaving to cause trouble downtown.

In less than two hours, the Guard had the situation under control. The students had been forced back into their dorms. The outsiders had been repelled from campus.

Helicopters flew overhead, lighting up dark corners and illuminating the lingering haze of discharged tear gas.

The ROTC building was allowed to burn to the ground.

Throughout the night, hot embers continued to set off ammunition that had been stored inside, the occasional popping sound of an exploding bullet echoing through the campus.

Sources: J. Ronald Snyder Oral History, Kent State University Libraries. Special Collections and Archives; The May 4 Shootings at Kent State University: The Search for Historical Accuracy (1998) by Jerry M. Lewis and Thomas R. Hensley; Thirteen Seconds: Confrontation at Kent State (1970) by Joe Eszterhas and Michael D. Roberts; Kent State: What Happened and Why (1971) by James A. Michener.