Investigators look for answers on nearly deserted campus; world takes notice

By Paula Schleis for the Akron Beacon Journal

May 5, 2020

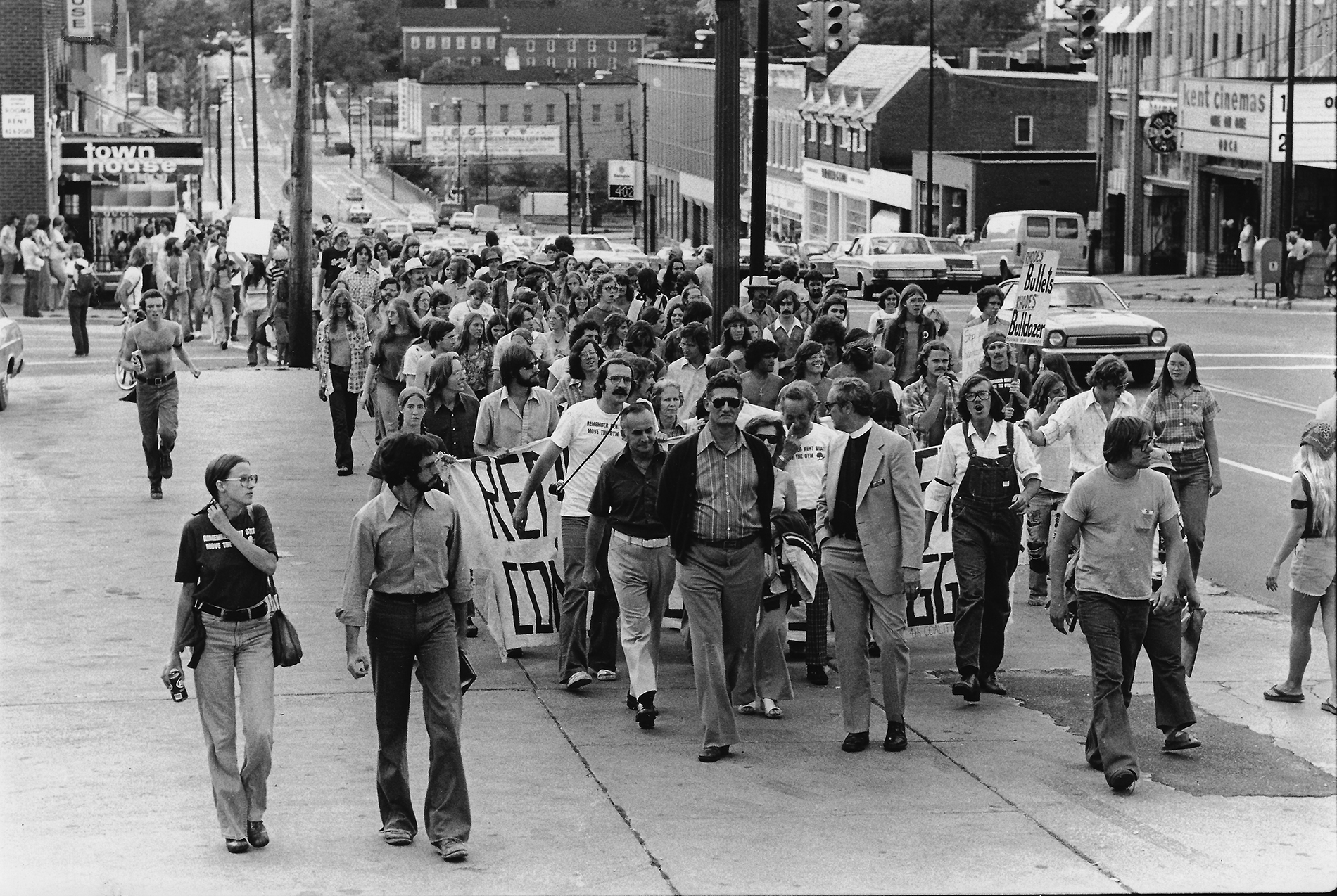

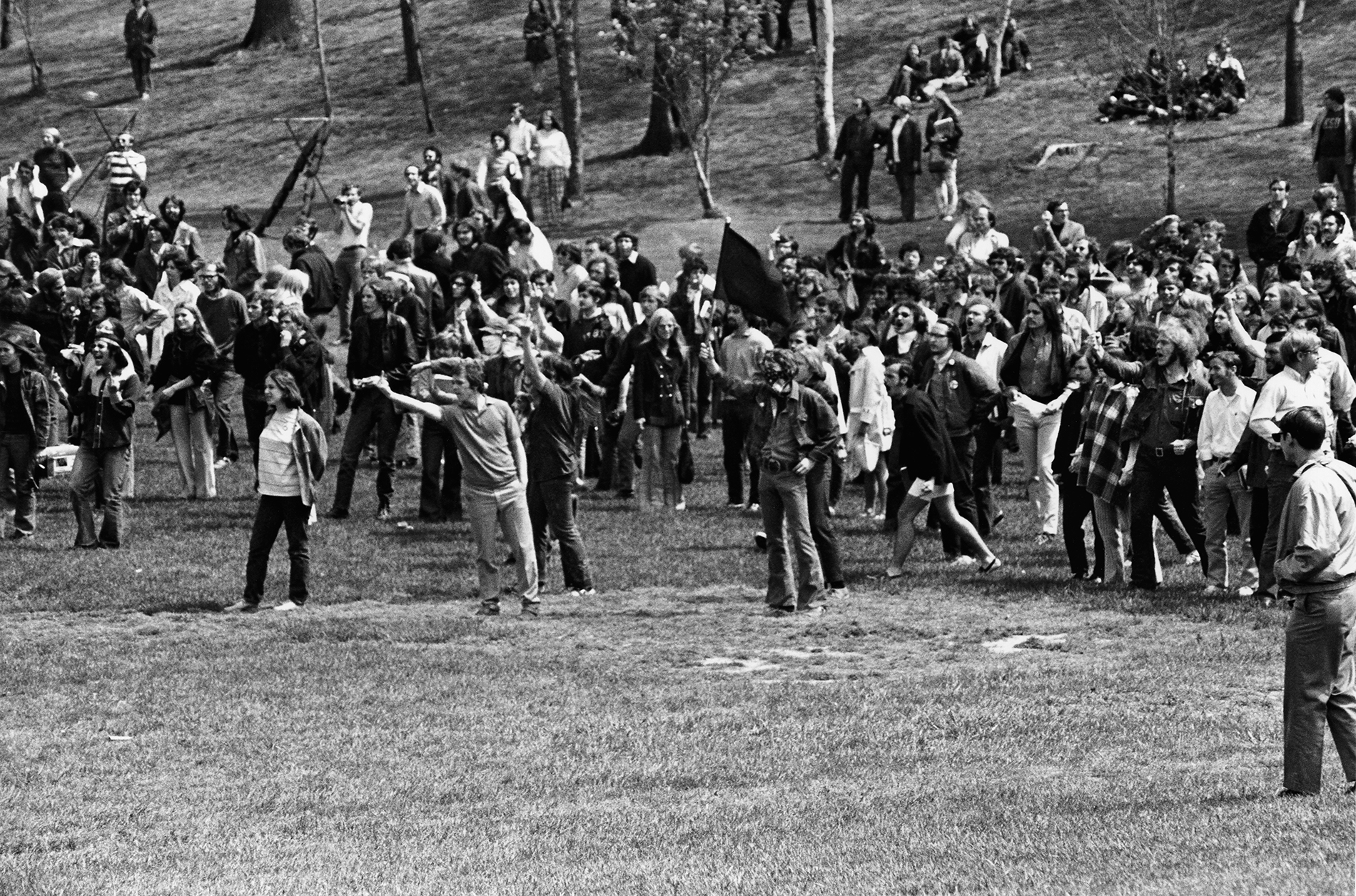

MAY 5, 1970: KENT STATE CLOSED; NATION REACTS

Editor’s note: This is the last of a seven-part series that relived the days leading up to the May 4, 1970, shootings at Kent State University through the lives of some of those most affected. Today, the aftermath.

Morning broke Tuesday over a nearly deserted Kent State University campus. A flag at half-staff rippled in the cool breeze over the administration building.

After a deadly clash the day before between the Ohio National Guard and students demonstrating against the Vietnam War, KSU President Robert White gave the order to evacuate the school. In four hours, every classroom, every dorm room and every office was emptied.

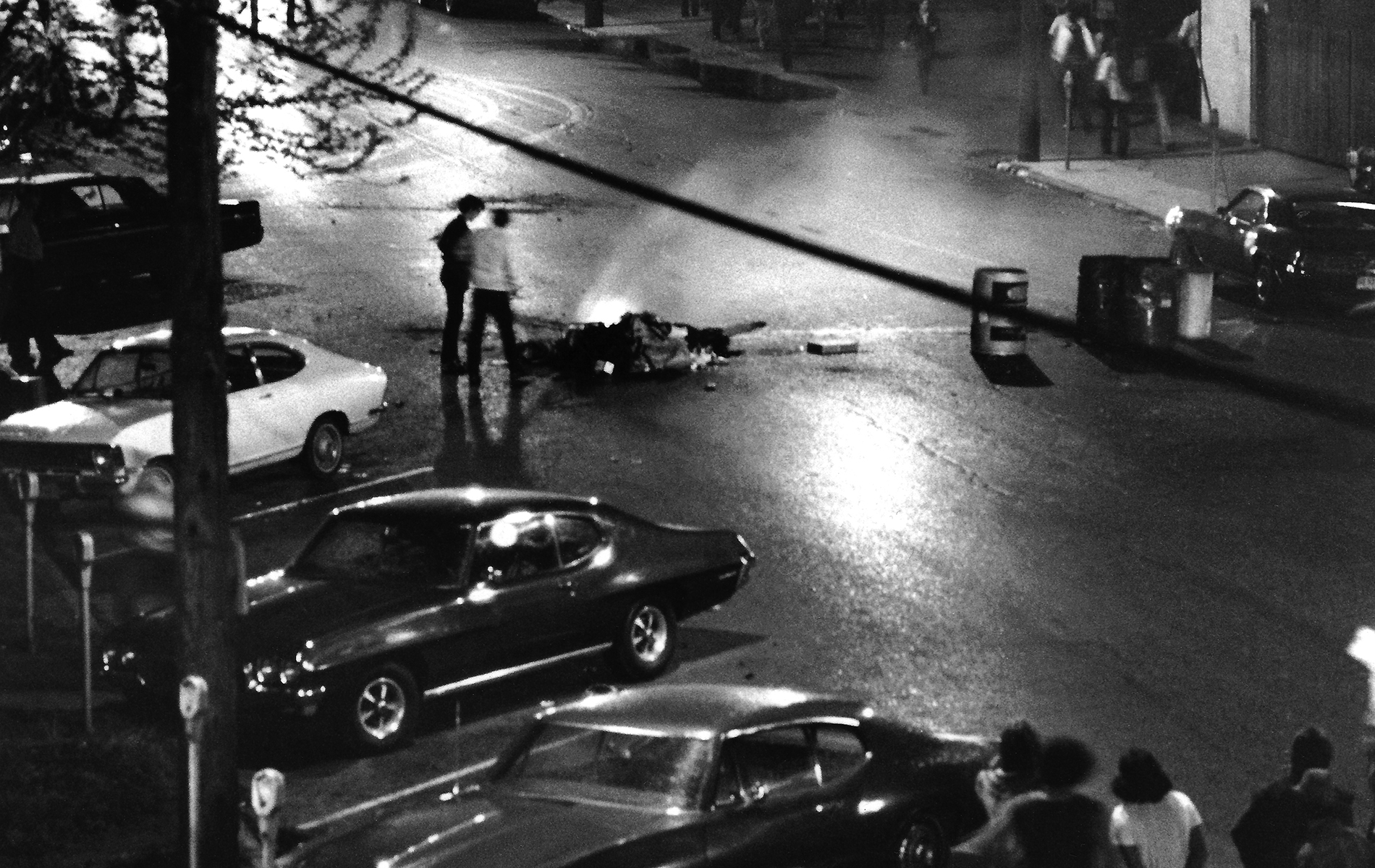

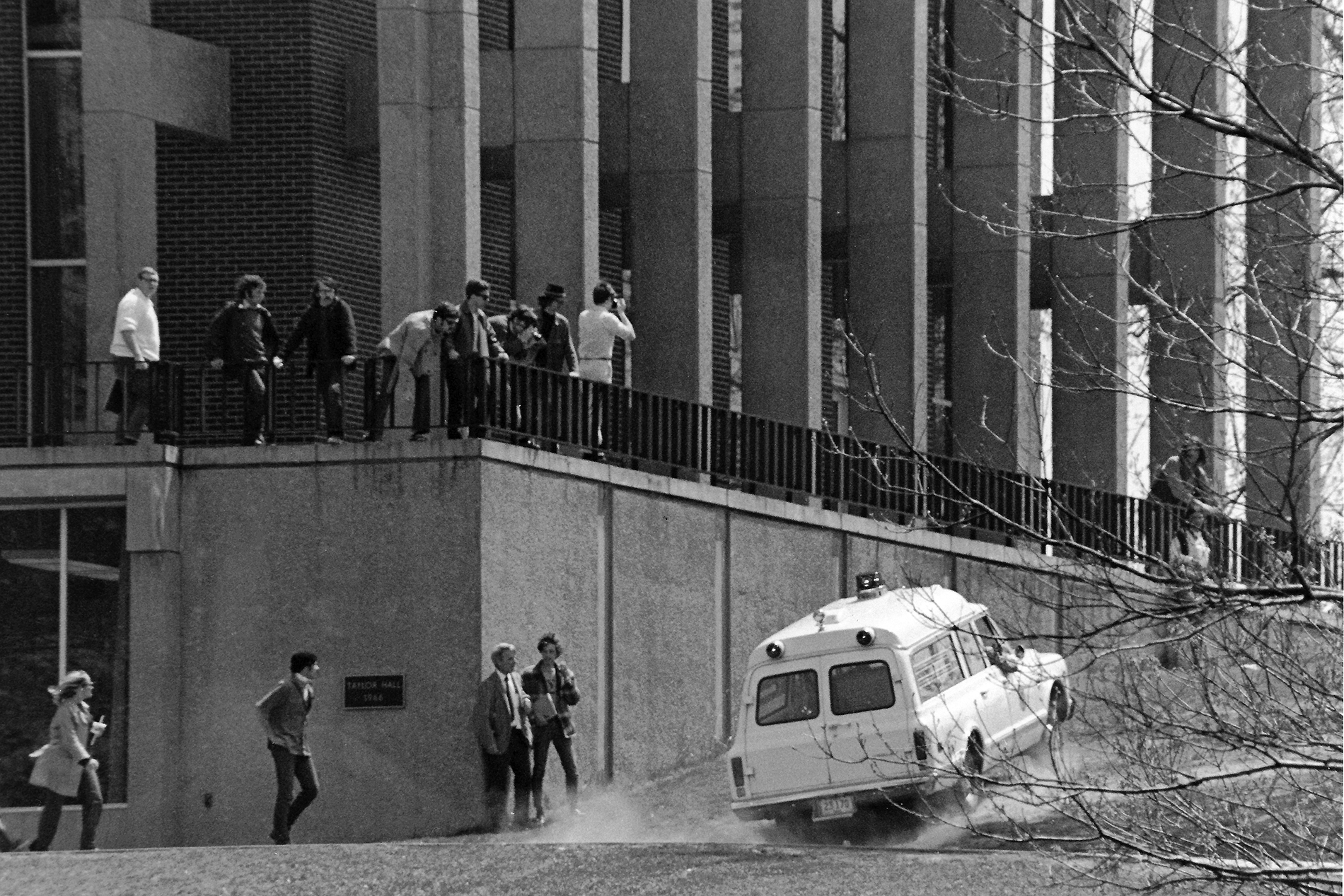

The only activity of significance now was outside Taylor Hall, where federal investigators toured a blood-stained scene, and on the Commons, where a hundred or so soldiers in olive drab waited to be interviewed.

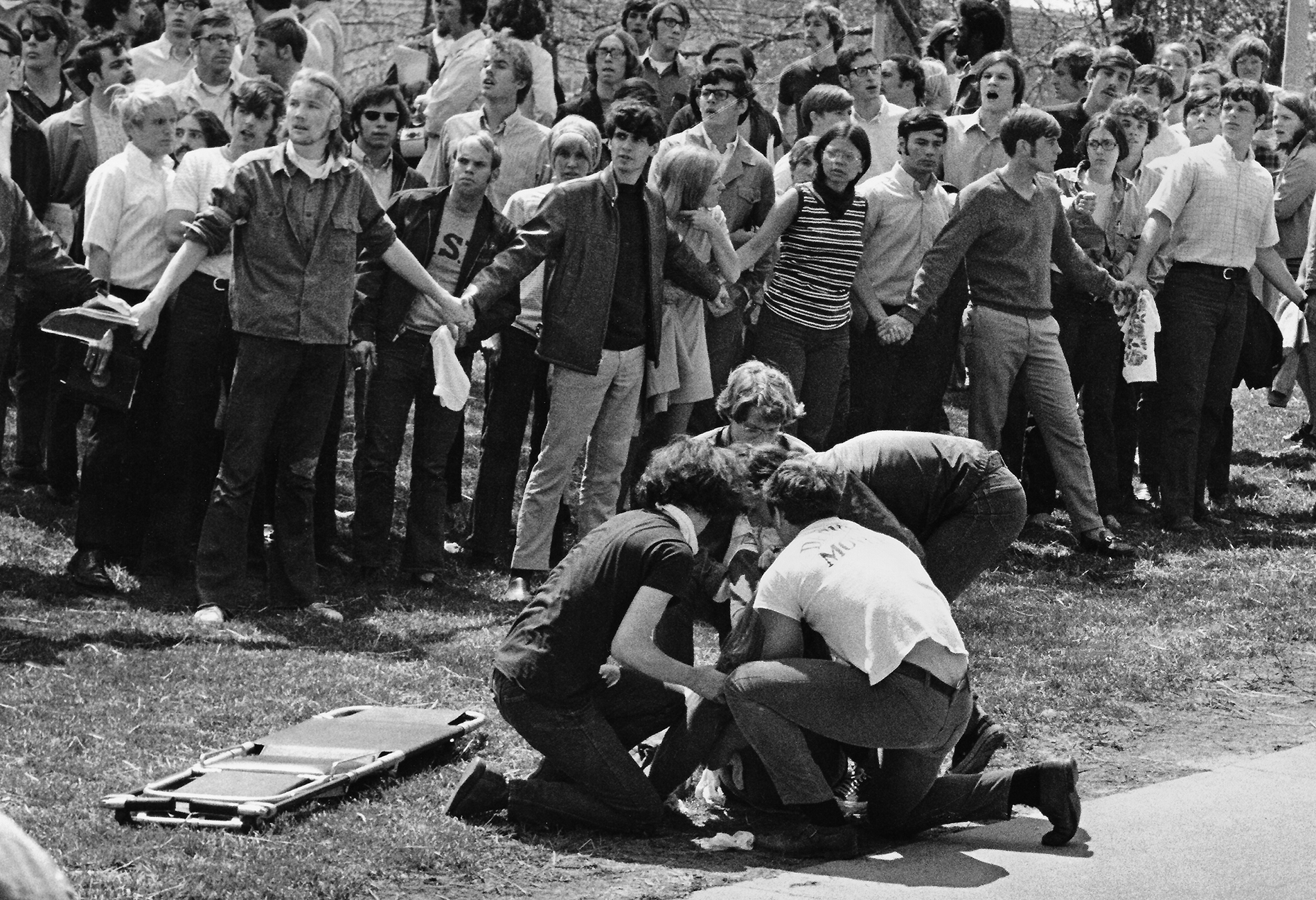

In a volley that had lasted 13 seconds, four unarmed students were killed, and nine were wounded. Now it was time to trace each of the 67 rounds that were fired. Who shot it? What did it strike? Why was it fired at all?

Students carry suitcases as they leave a dormitory after the Kent State campus was closed on May 4. Buses were brought in to transport students off campus, which was deserted by nightfall. Bill Hunter | Akron Beacon Journal

Brig. Gen Robert Canterbury, who commanded the Guard, met with reporters. He spoke slowly, choosing his words carefully.

No one had given an order to fire, he said, but soldiers are allowed to defend themselves. The Guard had run out of tear gas. Baseball-sized rocks were being lobbed their way.

“Conditions on the hill were extremely violent. I feel they were in danger,” Canterbury said.

But he backed off a statement he had given immediately after the shooting – that an unidentified protester had fired the first shot.

“I don’t know if there was any firing from the crowd,”Canterbury acknowledged after troopers with the Ohio State Patrol denied reports that they had seen a sniper.

National Guardsmen look at bullet marks in the turf of Blanket Hill on May 5, 1970. The men went through the area, marking everything that might have been a bullet mark for the ballistic experts. Kneeling at left is Lt. Col. Charles Fassinger, the troop commander. Bill Hunter | Akron Beacon Journal

Other guardsmen were shaken. Sure, there had been a lot of shouting, a lot of anger directed their way, but they had never felt their lives were in jeopardy, some told reporters who agreed to protect their identities. They were as confused as anyone as to what had inspired such a show of force.

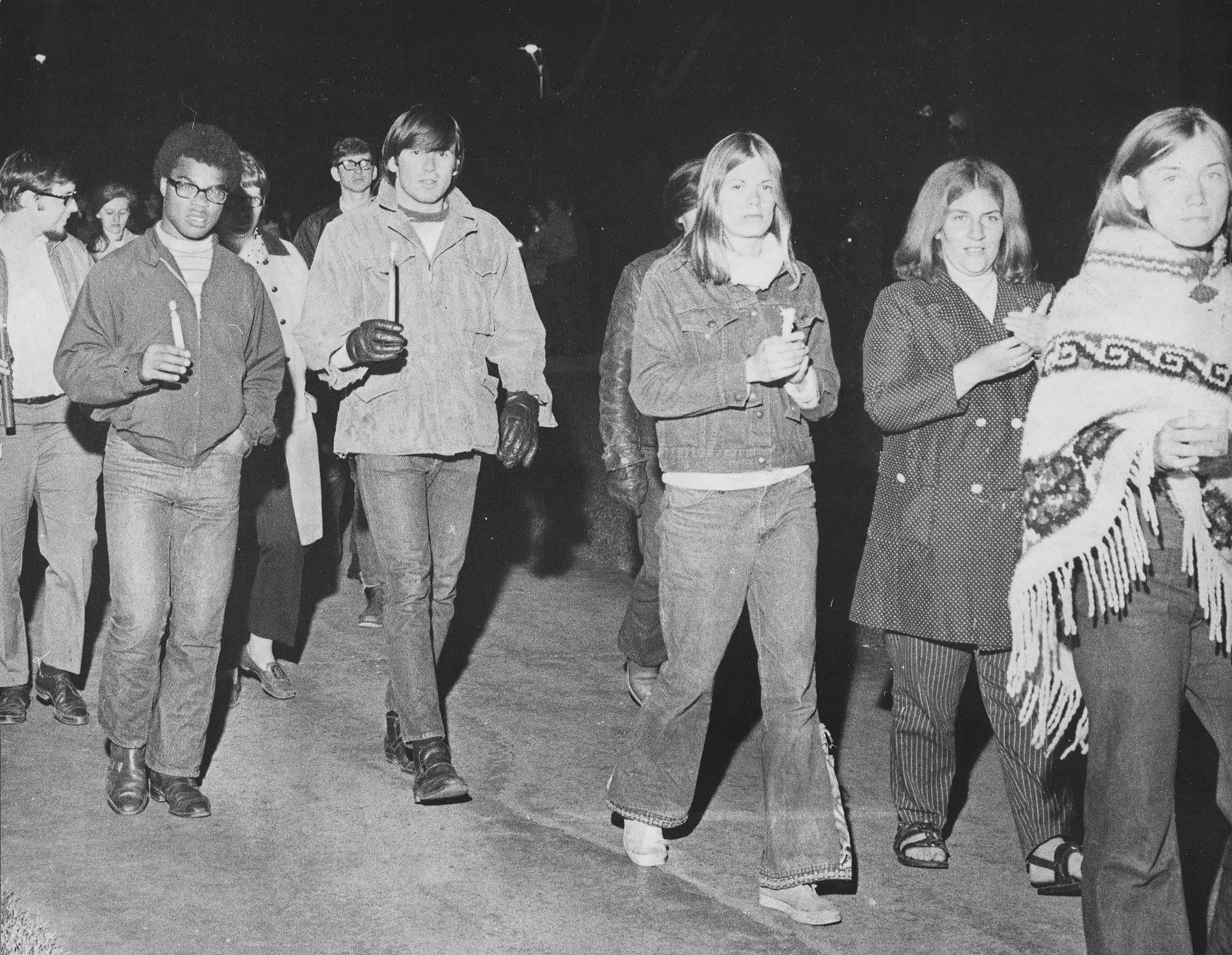

Outside Kent, the world weighed in on the tragedy. For years, anti-war demonstrations were a staple of college campuses. Some had even sparked gunfire. But this was the first time one had ended in death.

Within hours of the shooting, college students around the country responded with organized vigils and memorials. At Case Western Reserve University in Cleveland, 2,500 candle-carrying mourners marched behind four empty caskets.

Americans were divided on who were the villains and who were the heroes.

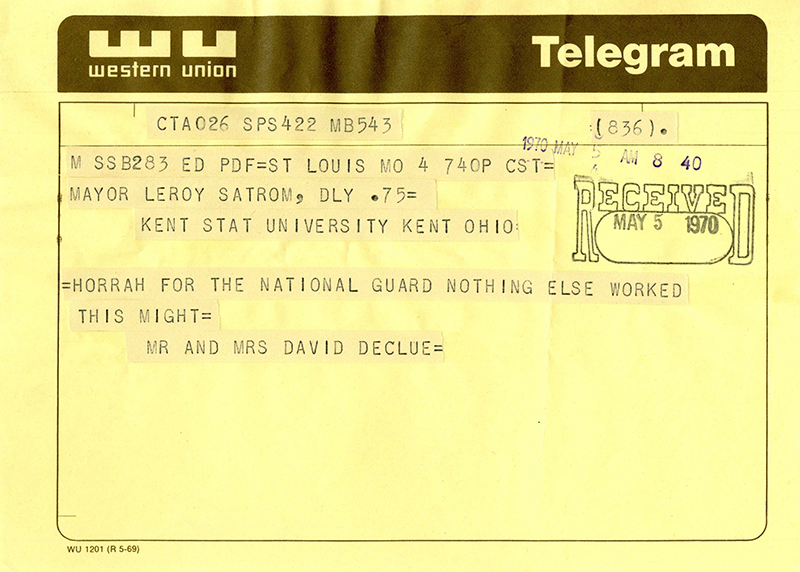

At Kent City Hall, Mayor LeRoy Satrom sifted through telegrams from people who had learned the details on their nightly news.

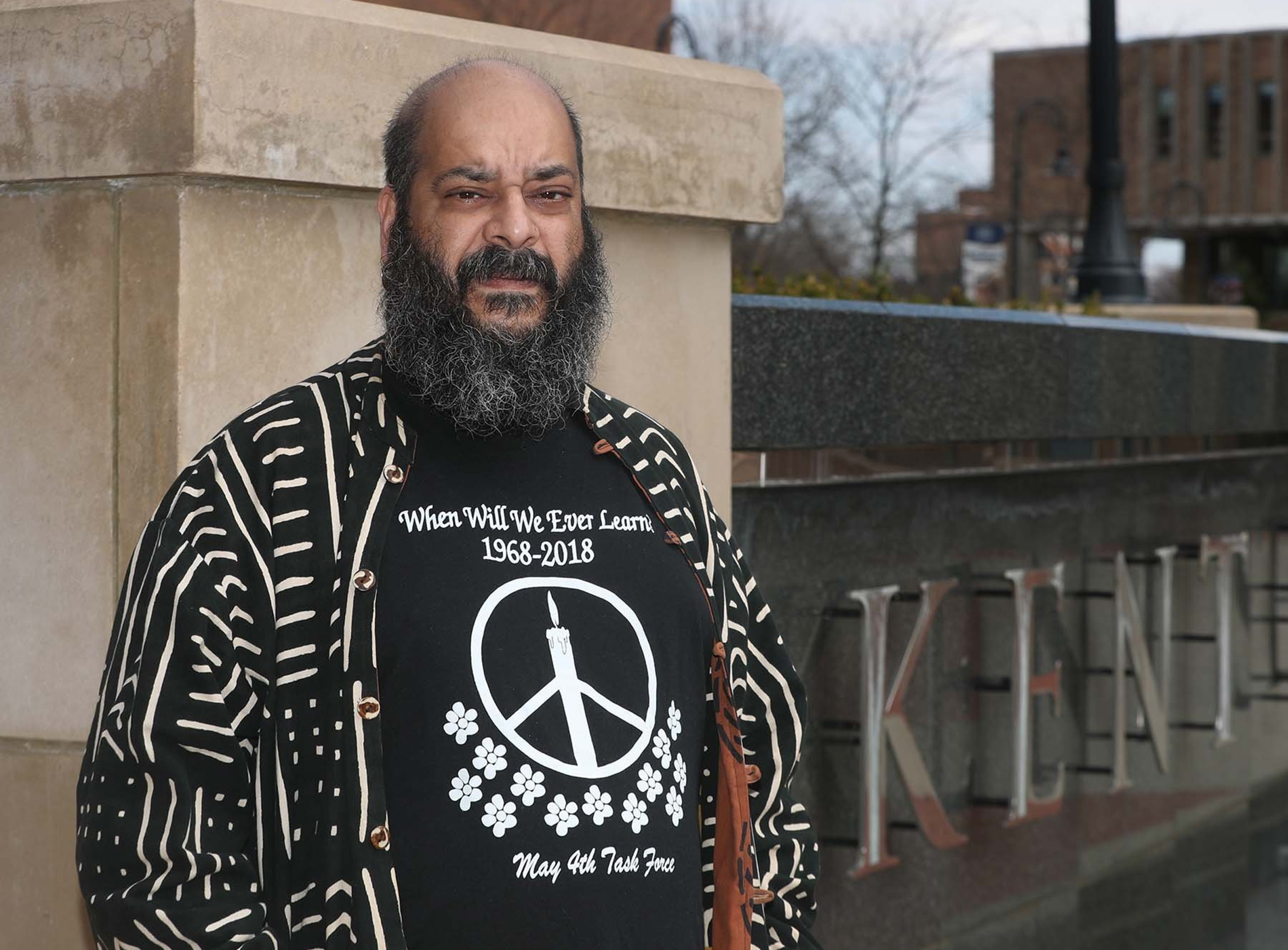

A telegram sent to Kent Mayor LeRoy Satrom on May 5, 1970, celebrating the Ohio National Guard’s shooting of four students at Kent State the previous day. Kent State University Libraries | Special Collections and Archives

“HORRAH (sic) FOR THE NATIONAL GUARD NOTHING ELSE WORKED THIS MIGHT” said a Western Union missive relayed from St. Louis, Missouri.

“THIS IS AN AFFRONT TO AMERICANS EVERYWHERE. THAT PROTESTORS CANNOT PROTEST WITHOUT BEING SHOT DOWN,” said another arriving from Los Angeles.

Satrom had ordered the city locked down. The local school district remained closed. Businesses stayed shuttered. All traffic was halted at the city’s border.

Police patrolled the streets in cruisers with windows taped to make them shatterproof. Other officers took up posts inside downtown buildings, their riot guns poking ominously out open windows.

“Don’t move around town tonight,” a patrolman cautioned someone, hinting at frayed nerves that were ruling the day. “They will probably shoot anything that moves.”

The dead were already gone. Four sets of parents traveled to Kent on Monday to identify their sons and daughters and make arrangements to take them home.

Three of the four were Jewish, a faith that encourages speedy burial in keeping with the teachings of the Torah.

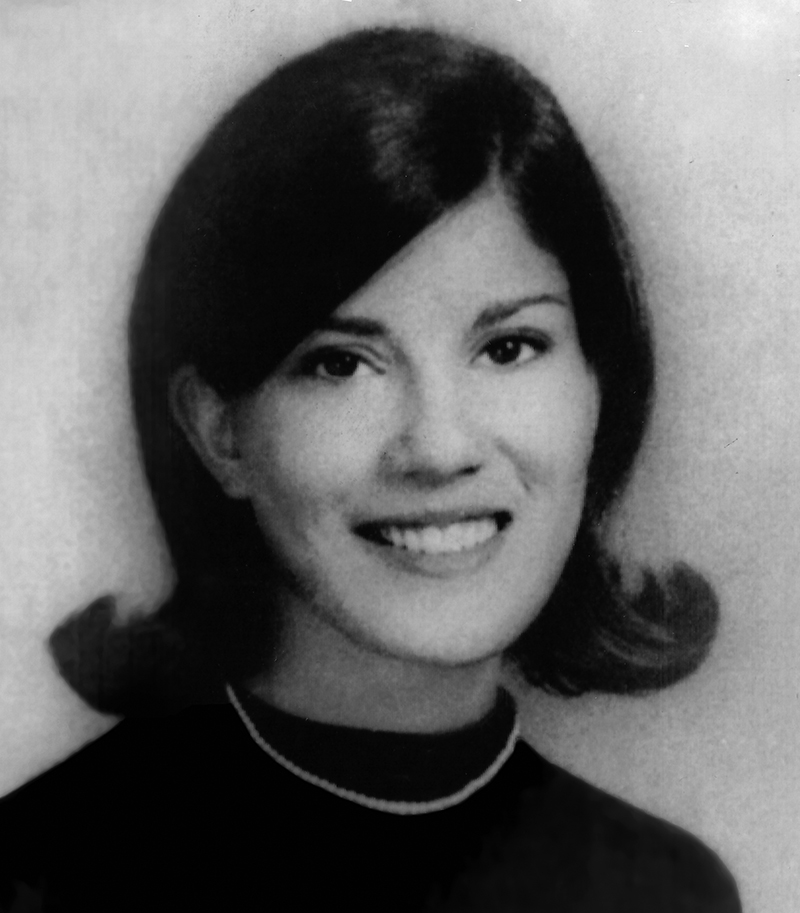

And so on Tuesday, while Justice Department investigators were still making their way to Kent, Sandra Scheuer was laid to rest at Ohev Tzedek Cemetery in Canfield, her family supported by friends who knew Scheuer as a sweet and non-confrontational woman. She was a junior studying speech therapy, killed while walking to class.

The parents of Allison Krause set their daughter’s service for Wednesday in Pittsburgh. The past weekend, Krause’s boyfriend snapped a picture of her chatting with a guardsman who had a lilac sprouting out of his gun barrel. On Monday, a rifle of the same type was aimed at her as she took refuge behind a parked car.

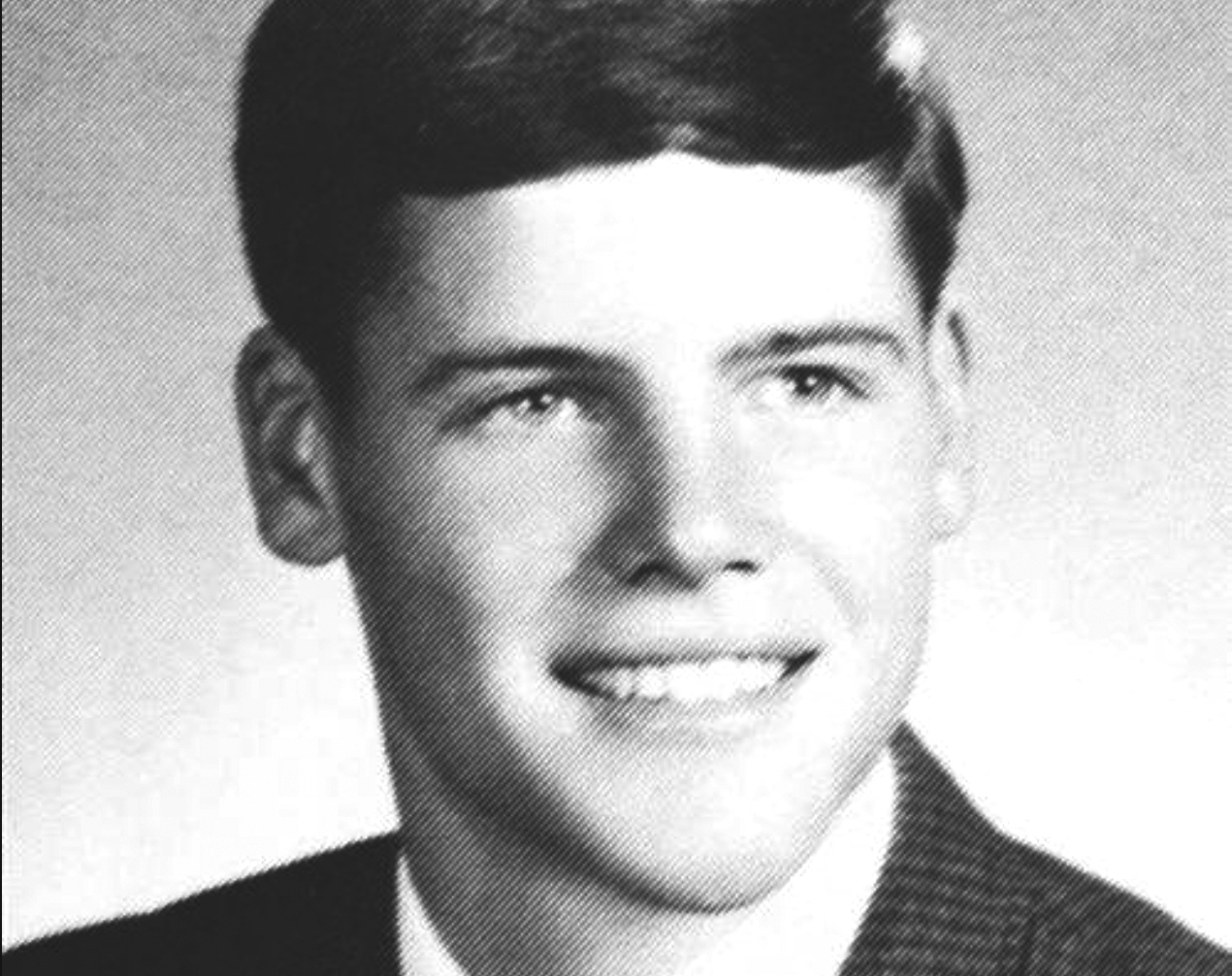

The last two funerals took place Thursday: William Schroeder’s in Lorain; Jeffrey Miller’s in Plainsview, New York. Both were psychology majors who opposed the war, though they took different paths to express it.

Schroeder joined the ROTC, hoping to understand war from the inside and use the skills he was learning to treat battle-scarred soldiers. Miller despised violence from any side, but believed in the power of raised voices and public dissent.

Bullets didn’t discriminate between their views.

As the week wore on, the grieving families received cards, flowers and kind words from supporters, sometimes from unexpected sources. In New York, Gov. Nelson Rockefeller arranged a secret meeting at the home of Jeffrey Miller’s parents to offer condolences.

But there was no protection from the hate-filled envelopes that arrived in their mailboxes from strangers who wanted more blood to be spilled.

“There’s nothing better than a dead destructive, riot-making communist,” began one letter received by the Schroeders in Lorain.

Six days after events took the life of their daughter, Martin and Sarah Scheuer sat in the living room of their home in Boardman, trying to make sense of it all. The mirror over the mantle was covered with black cloth. A customary red candle burned on the table.

Carolyn Johnson (left), 22, from Chesterland, Ohio, gets some help from Phyllis Gongol, 23, from Canisteo, New York, May 18, 1970. Students returned to campus to pick up their belongings in residence halls as a result of the campus closure following the shootings. Ted R. Schneider | Akron Beacon Journal

Sarah Scheuer was bitter. She was angry at student radicals. At National Guardsmen. At the war in Vietnam. At college authorities for allowing all three forces to converge like a bloody high noon.

But even though their daughter had never attended a rally or march – had died an unwitting bystander – Martin Scheuer offered a word of caution to those who would silence the free expression of her generation.

After all, he’d escaped Germany as the Nazis came into power. He’d made his way to America because of its promise of personal liberty, because of the protections afforded by its constitution.

“We did not have the chance to develop like the children have here,” he said, recalling his own inhibited youth. “Because they are so free — and they should be free to express their feelings and their thoughts.”

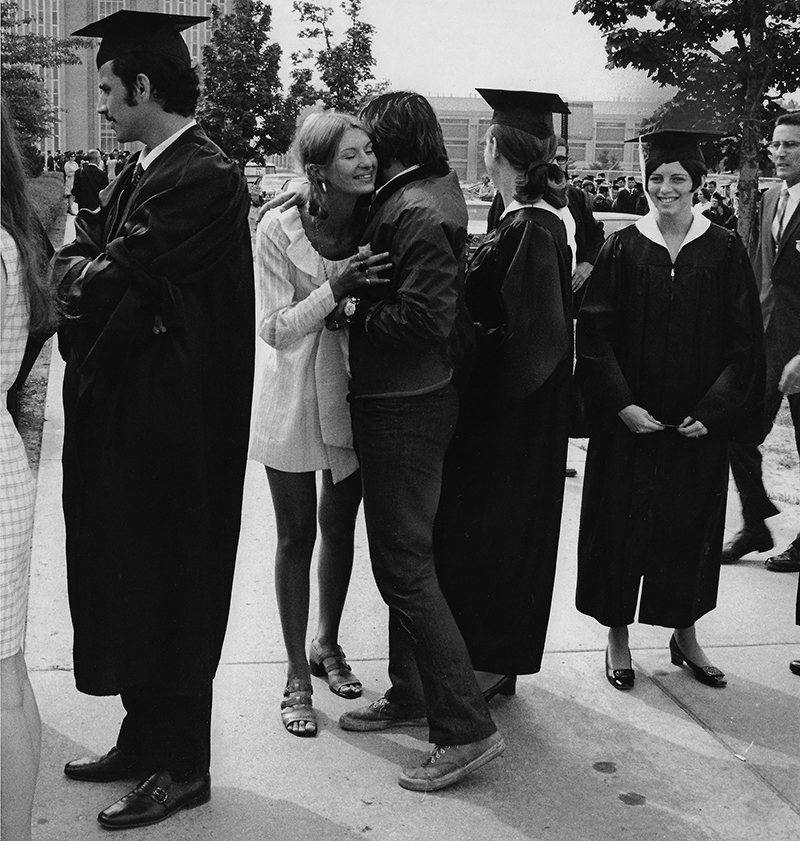

Tammy Rogers of Wooster gets a hug during the commencement parade on June 13, 1970, prior to graduation ceremonies at Kent State University. The ceremonies marked the first large gathering on campus since the campus closed following the shootings on May 4, 1970. Lew Henderson | Akron Beacon Journal

Before the month is out, a nationwide student-led strike will temporarily shutter hundreds of college campuses. Forty days after their forced exodus from campus, some 1,250 seniors and graduate students will return to receive their degrees. For everyone else, classes resume on June 15.

In July, a Justice Department report will conclude the shootings “were not necessary and not in order,” that there was no hail of rocks thrown before the shooting, and that no guardsmen were in danger of losing their lives.

In August, Ohio National Guard Capt. J. Ronald Snyder will tell author James Michener he took a gun off the body of Jeffrey Miller. Years later, he will testify in court that he lied.

In 1974, a federal grand jury will indict eight former guardsmen. They will be acquitted by U.S. District Court Judge Frank J. Battisti.

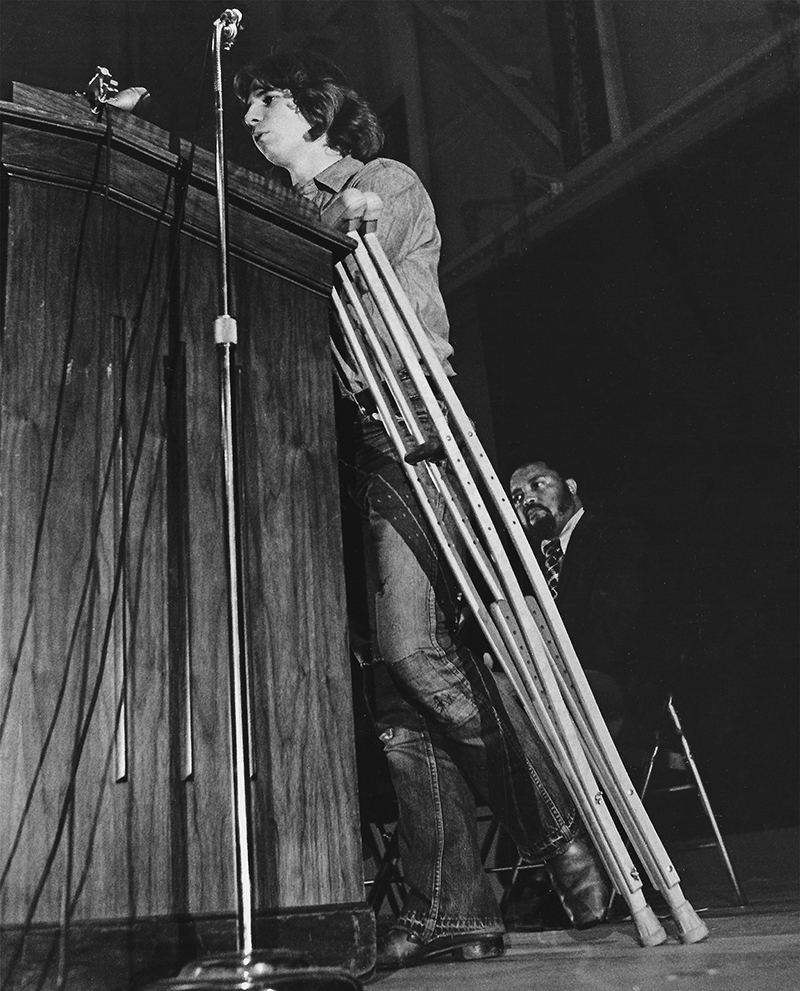

In 1979, a civil case brought by the parents of the slain and the students who were wounded will be settled out of court for $675,000 and a “letter of regret”; from the State of Ohio. More than half of the settlement will go to Dean Kahler, a survivor of the shooting who was left paralyzed.

Sources: MAYDAY: Kent State (1981) by J. Gregory Payne; Akron Beacon Journal; Kent State University Libraries Special Collections and Archives; Akron Beacon Journal; Youngstown Vindicator.