Kent State shootings: What made Mayor Satrom request the National Guard

By Paula Schleis for the Beacon Journal

May 1, 2020

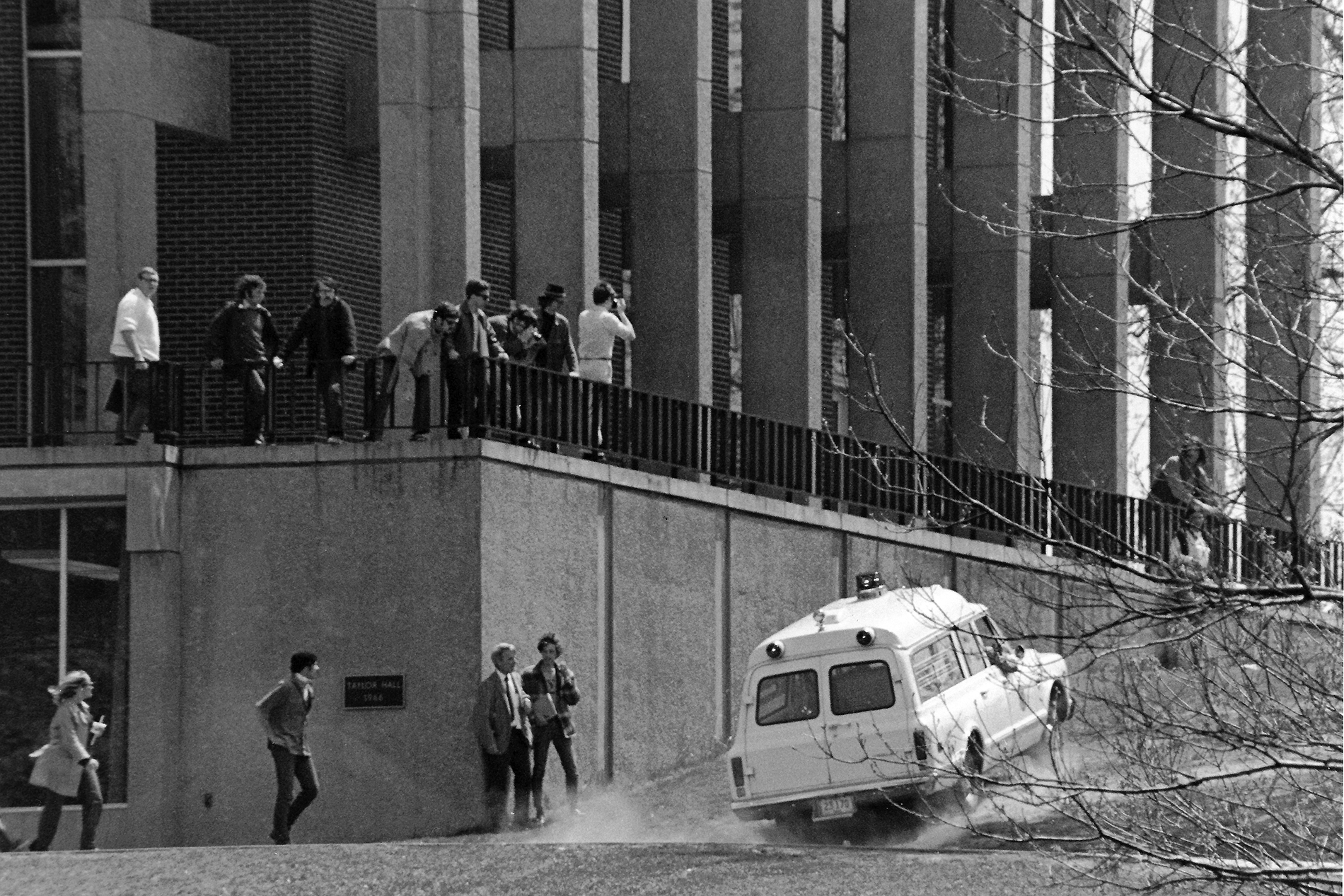

MAY 1, 1970: UPSET STUDENTS RIOT IN KENT

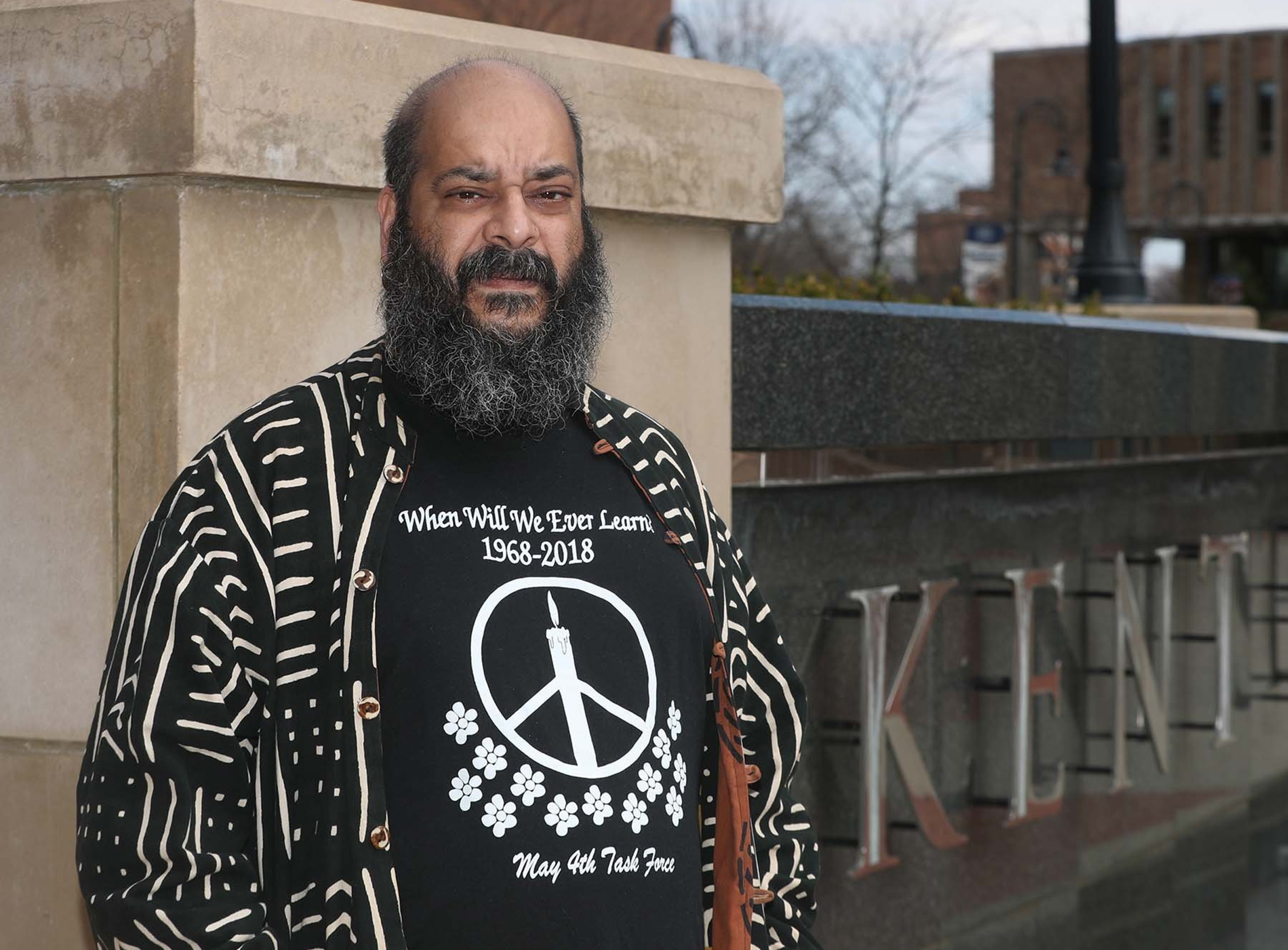

Editor’s note: This seven-part series relives the days leading up to the May 4, 1970, shootings at Kent State University, through the lives of some of those most affected. Today, the events of Friday, May 1, 1970, and the life of Kent Mayor LeRoy Satrom.

LeRoy Satrom thought his day was ending on such a promising note.

He’d gone to a friend’s house for some Friday night poker and was enjoying a streak of luck. Five winning hands in a row.

Then the phone rang. The mayor was needed back in Kent. He assured his pals he wasn’t trying to bolt with his winnings, but duty called.

Now it was midnight, and Mayor Satrom was staring at a war zone.

Circumstances had put him behind the steering wheel of a police cruiser on North Water Street, where the window of every business lay shattered on the sidewalk. There were random chunks of concrete and wood laying about. A bonfire blazed in the middle of the road.

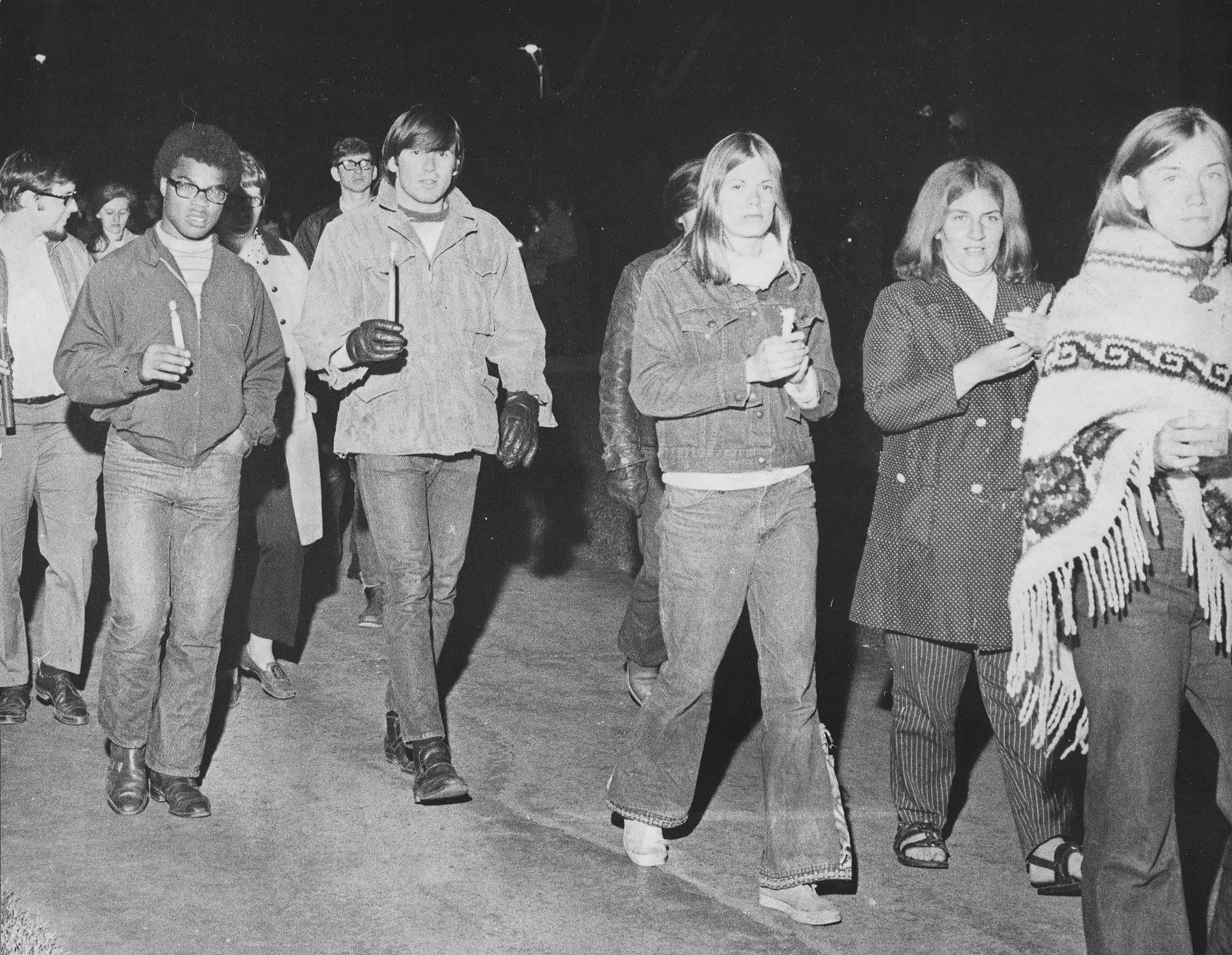

Hundreds of Kent State University students were being herded toward the campus by city police dressed in riot gear and lobbing tear gas.

A police officer leaned through the window of the cruiser and gave Satrom a quick lesson in how to work the lights and siren. He needed Satrom to take an arrested youth to the jail; the officer couldn’t be spared to do it himself.

Satrom punched the right buttons, lit up the car and played his role.

Satrom had moved into the mayor’s office four months ago.

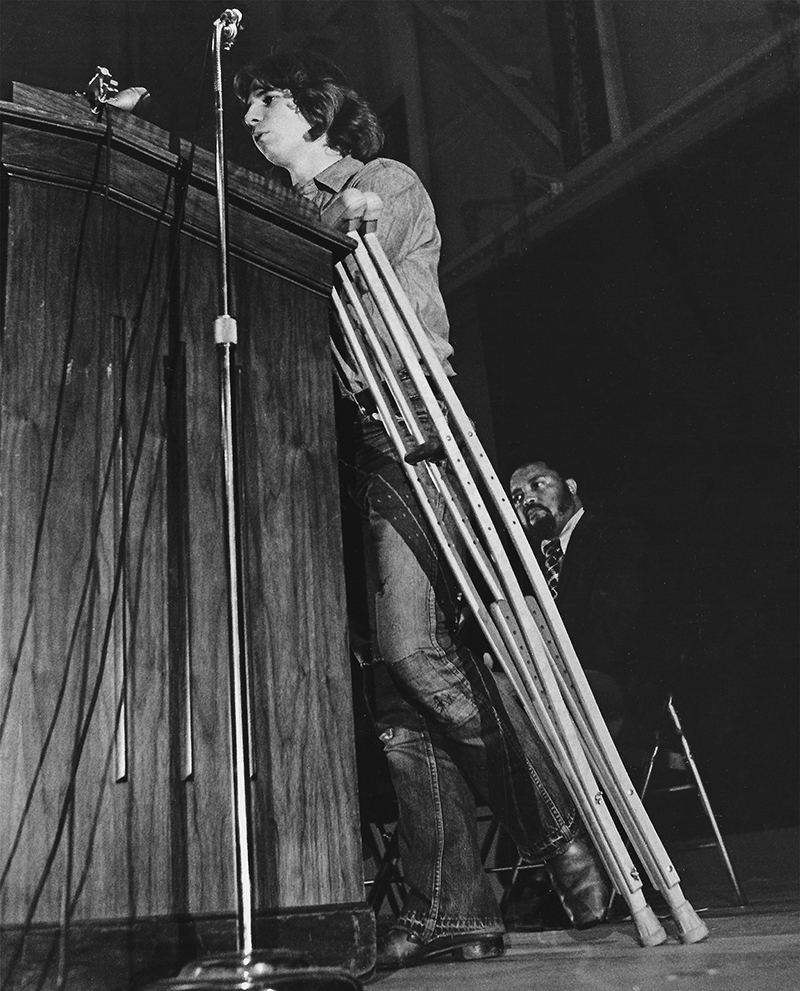

LeRoy Satrom, the mayor of Kent, testifies Aug. 20, 1970, before the President’s Commission on Campus Unrest at Kent State, also known as the Scranton Commission, a nine-member commission appointed by President Richard Nixon to examine campus violence and recommend ways of peacefully resolving student grievances and avoid future incidents such as the one at Kent. The panel was headed by former Pennsylvania Gov. William W. Scranton. Ted Walls | Akron Beacon Journal

He was North Dakota-born, but had spent most of his professional career in Northeast Ohio after earning his civil engineering degree from Case Institute of Technology.

He’d spent time working on the Panama Canal locks before joining the Army in 1943 and serving in Europe during World War II, then settled in Portage County where he held a variety of city and county engineering positions.

Satrom and his wife, Grace, raised three sons at their home on Morris Road. Two sons, Jim and Bob, still lived with them. Son Tom was a medical student at Ohio State University.

A lifelong Democrat, politics had also become part of his life. He got himself elected to the Kent City Council in 1963, and when the good citizens of Kent elected him mayor the previous fall, they also made the job full time.

Still, Satrom expected the job would be handling the same kinds of duties as his part-time predecessors. His campaign talked about improving streets and making city services more efficient.

Former executives had spent their days planning budgets and negotiating with unions, not planning riot control and negotiating peace.

The most common trouble that spilled into the city side of this college town – where 18,000 residents were outnumbered by 21,000 students – were freshmen trying to buy beer before their 18th birthdays.

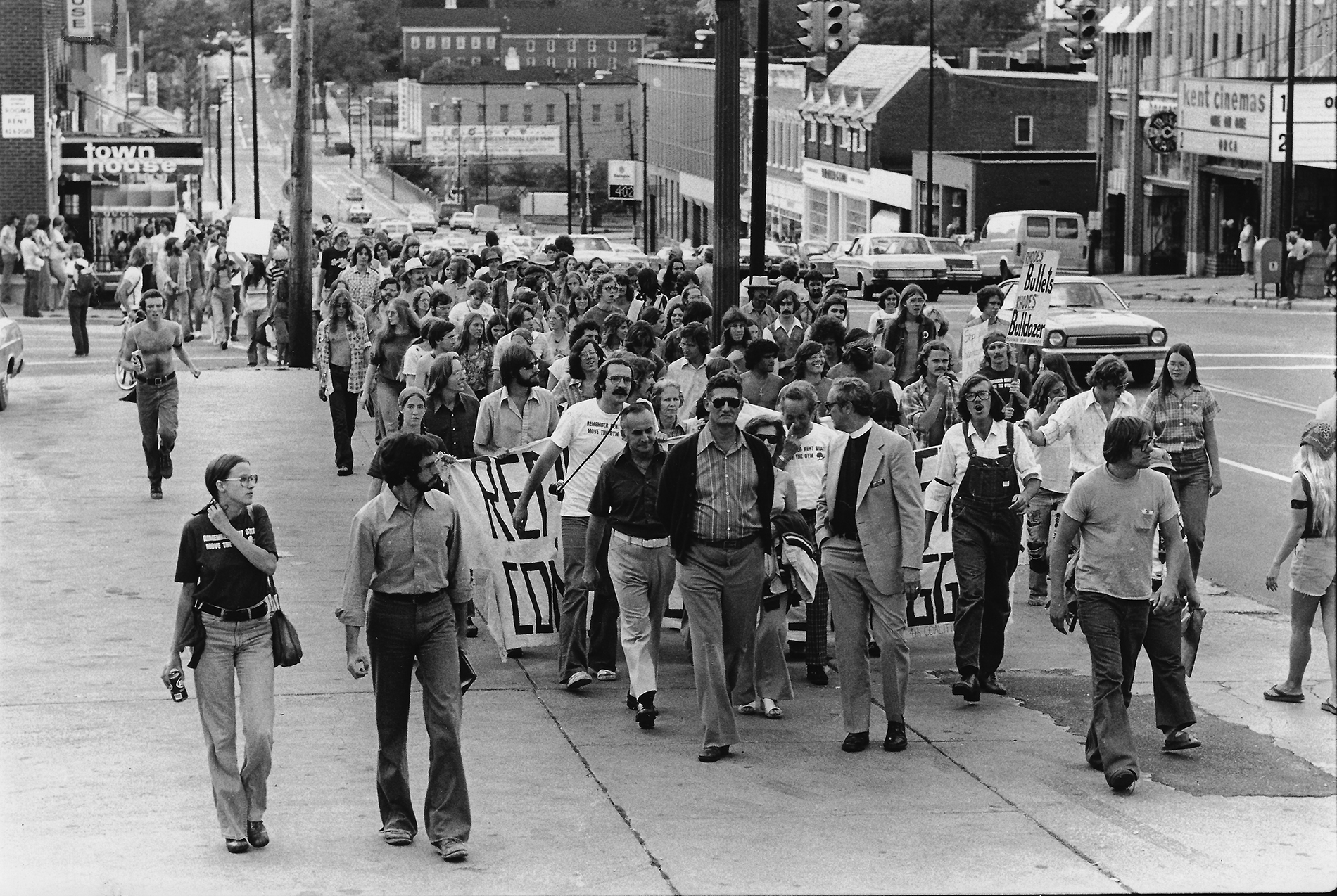

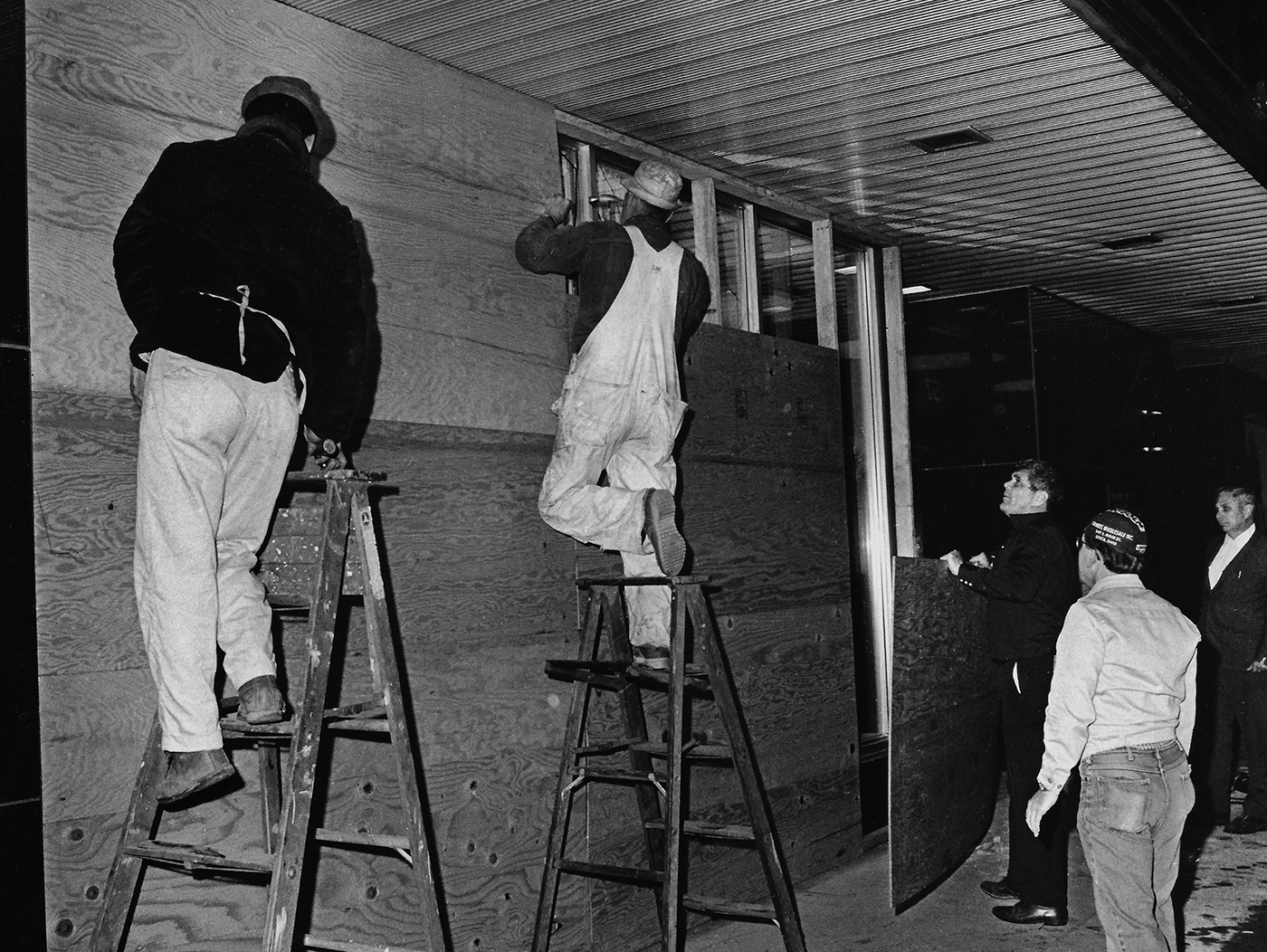

Workers board up broken windows on the First Federal Savings Bank building after vandals damaged a number of buildings in downtown Kent Friday night, May 1, 1970. Paul Tople | Akron Beacon Journal

Of course, current events had given authorities reason to be nervous. The night before, President Richard Nixon had announced the Vietnam War was expanding into Cambodia. A few students responded by showing up downtown to spray paint anti-war graffiti on businesses.

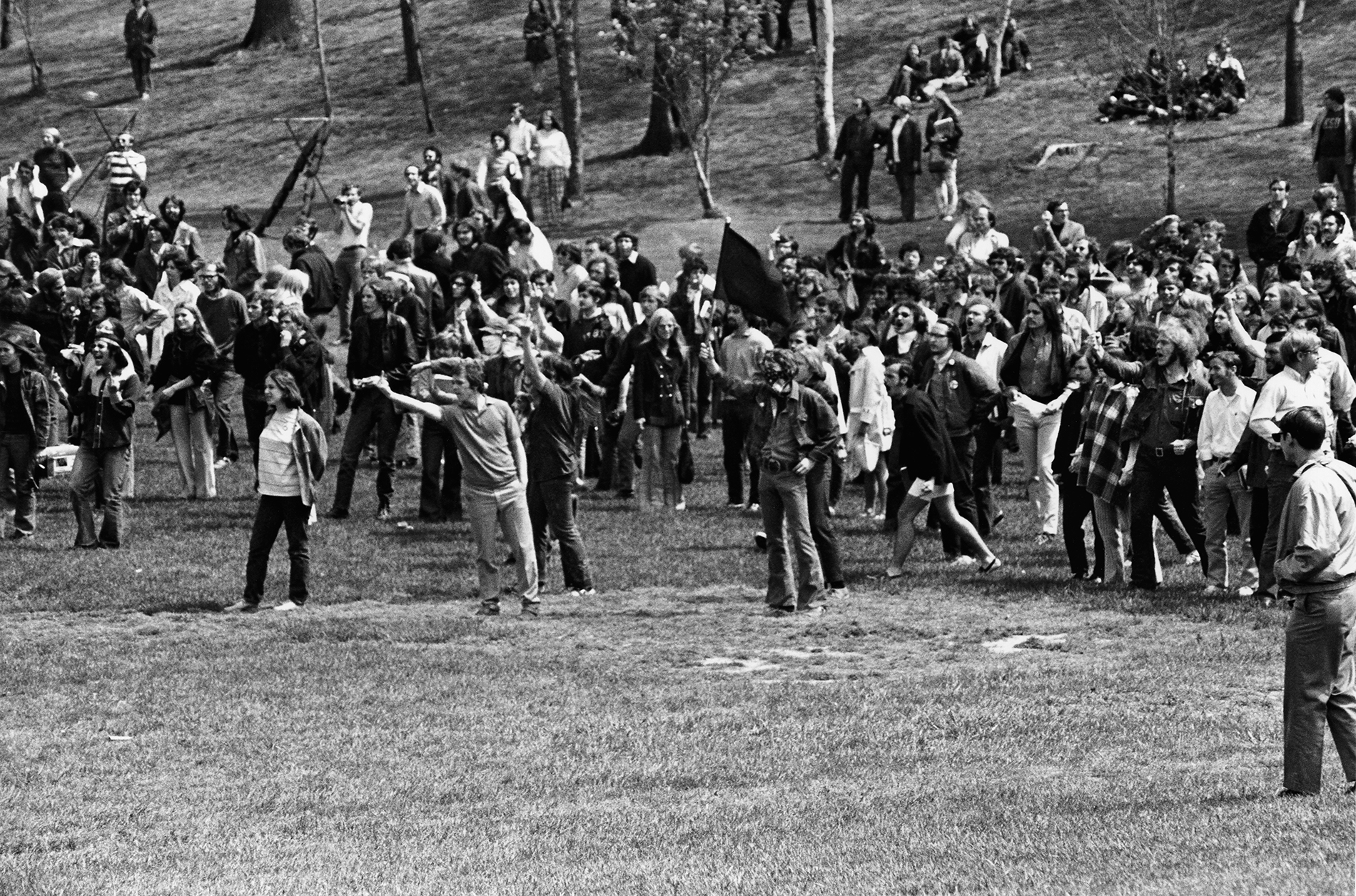

But the sun rose, and the day progressed peacefully. A few hundred students turned out for two rallies on the campus Commons. It was so non-threatening that KSU President Robert White kept his plans to fly out of town that afternoon.

Even that night’s riot began as a typical evening downtown, with students filling the bars along “the Strip” on North Water Street.

The weather was so warm, hundreds of people collected outside, effectively closing the streets as they spilled off the sidewalks and created a festival type atmosphere. Radios played. Students pitched pennies. Someone yelled out updates for the NBA playoffs.

When a police car tried cruising through, it was struck with a beer bottle. Police Chief Roy Thompson told officers to leave the area. Better to let the students continue their party than set off the crowd.

But shortly before midnight, the mood of the mob changed anyway. A motorist – an elderly man with his wife – insisted on trying to drive through the crowded street. When students refused to move, the car brushed one of them. Someone responded by smashing his car windows.

Suddenly, a handful of revelers took it to the next level, hurling rocks and bottles at all the windows along North Water and starting a bonfire in the middle of the street.

Mayor Satrom listened as Chief Thompson filled him in on what happened next.

Unable to ignore the crowd-turned-mob, the chief called in his full 22-man force and fitted them with helmets, face shields, batons and tear gas.

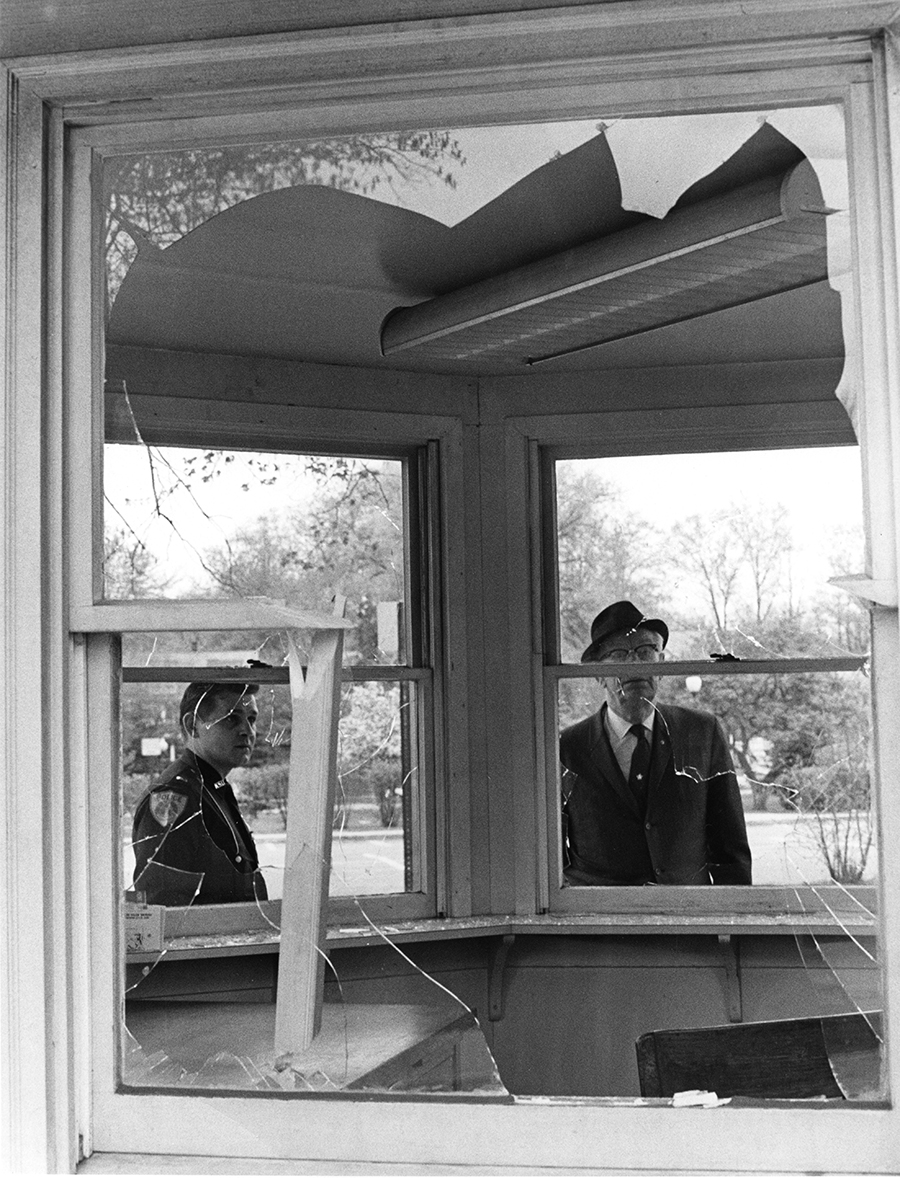

A Kent State policeman and Emil Berg, Kent State’s business manager, survey the smashed windows in the visitor information kiosk on campus near Rockwell Hall following a night of vandalism on May 1, 1970. Protesting students left many Kent businesses with broken windows and damaged buildings. Courtesy of Kent State University Libraries | Special Collections and Archives

He put out the call for help from the Portage County sheriff and any neighboring community that could spare an officer. Anyone who stopped into the police station to complain about the mob was deputized.

He also called KSU’s campus police, but they declined. They had their own buildings to watch and protect, they told him.

Fearing the bars would liquor up more potential dissidents, the chief made the arbitrary decision to order the bars closed. It was a decision that he instantly regretted as hundreds of more students poured from the businesses into the street, many of them angry at having their fun-loving night interrupted.

The officers yelled “Disperse!” at the crowd, but too many were reluctant to move. The officers formed a phalanx and shepherded the mob east on Main Street, toward the campus.

After Mayor Satrom dropped the arrested youth off at the city jail, he returned to downtown in the police cruiser, this time armed with a copy of the city’s emergency proclamation. He read “the riot act” over the loudspeaker as he drove toward the crowd. His car was pelted.

LeRoy Satrom, the mayor of Kent during the 1970 Kent State University shootungs, testifies August 20, 1970, before the President’s Commission on Campus Unrest at Kent State. Ted Walls | Akron Beacon Journal

And then, a surprise ending to the biggest riot the city of Kent had ever experienced.

Half a block from the arch that marked the entrance to the KSU campus at Main and Lincoln streets, two utility workers were fixing a traffic signal, the kind of work that was always better to do in the early morning hours.

They were 15 feet above their truck on a scaffold when a drunk driver veered into their vehicle.

One worker was knocked to the ground. The other threw a leg around the dangling light and cradled it while the scaffold collapsed beneath him.

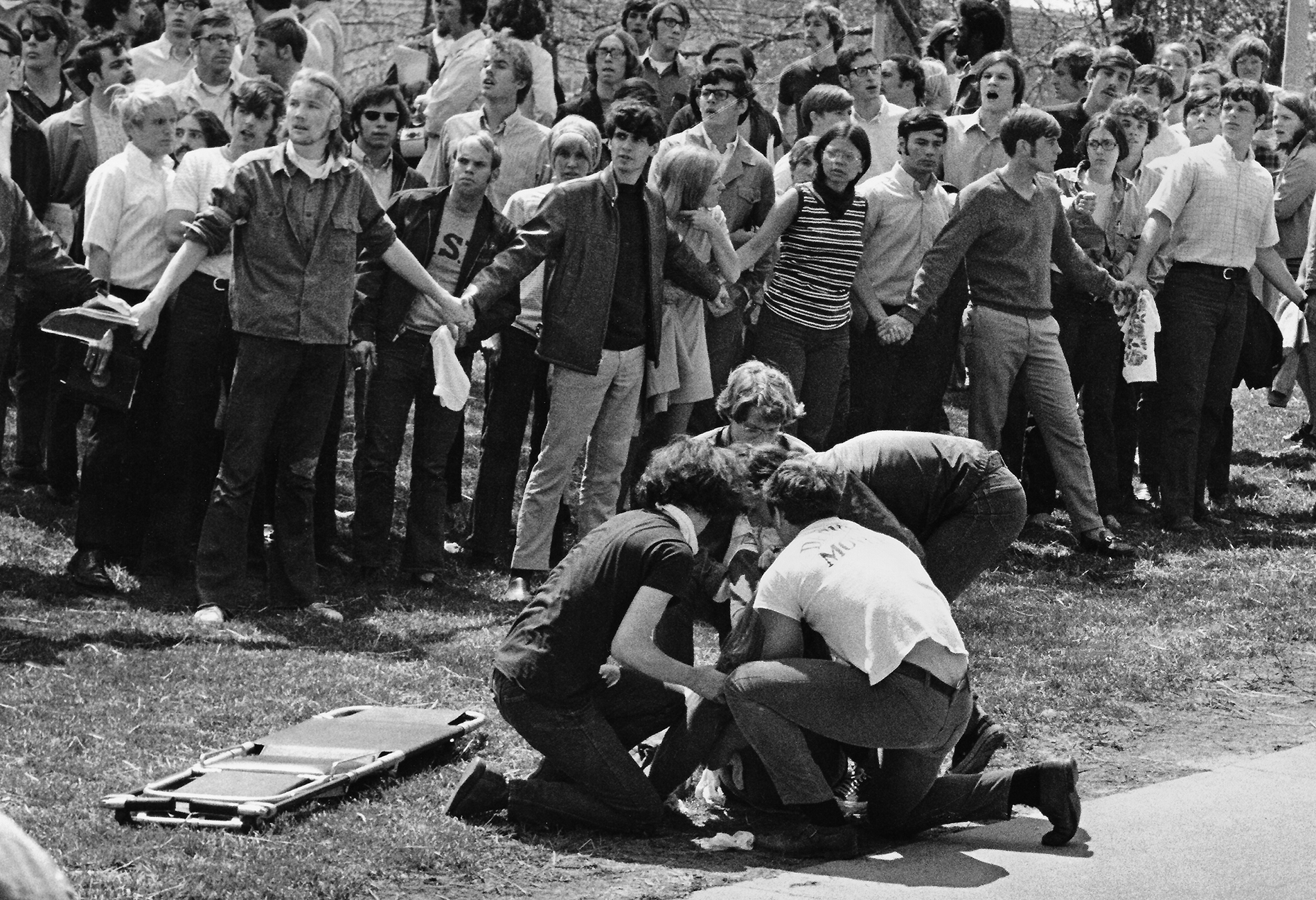

The fleeing students and pursuing police stopped at the scene, anger giving way to concern.

Students ran to the man on the ground and tucked jackets beneath his head while police called for an ambulance.

Other students positioned themselves below the worker dangling in the air, encouraging him to hold on and ready to catch him if he didn’t, while police called for a firetruck to rescue him.

And that was it. After the ambulance pulled away, the students walked to their dorms, and the police returned to the station.

Fourteen people had been arrested and seven policemen suffered minor injuries. Downtown, 43 windows had been broken.

Mayor Satrom knew Chief Thompson didn’t bargain for any of this. The gray-haired 59-year-old wanted to retire at the start of the year. A petition signed by 700 townspeople asking him to stay convinced him otherwise.

Ohio Gov. James Rhodes, at center with papers in his hands, holds a press conference at Kent State University on May 3, 1970, the morning after the ROTC building on campus was burned. To the left of Rhodes is LeRoy Satrom, the Kent mayor who requested the National Guard. To the right is Maj. Gen. Sylvester T. Del Corso, the adjutant general who headed the Ohio National Guard units on campus on May 4, 1970. File photo | Akron Beacon Journal

But the city’s police had never had to deal with something like this before. They weren’t even really prepared to deal with something like this.

Satrom listened as Chief Thompson encouraged him to put the National Guard on alert.

Before the sun rose, Satrom picked up the phone and called the adjutant general’s office in Columbus, using an emergency number available to city officials.

He relayed the events of the night and asked if the National Guard could be on standby, ready to assist in defending the town if there were another incident.

Yes, he was told. A liaison from the 145th infantry regiment would be there first thing Saturday morning for a meeting.

Sources: LeRoy Satrom papers at the Kent State University Department of Special Collections and Archives; Thirteen Seconds: Confrontation at Kent State (1970) by Joe Eszterhas and Michael D. Roberts; Kent State: What Happened and why (1971) by James A. Michener; Akron Beacon Journal.