Suspects run free while authorities drown in

open arrest warrants

illions of Americans are wanted on open arrest warrants, including hundreds of thousands of fugitives accused of murder, rape, robbery or assault, while victims wait for justice.

Many of the cases stay open for years, even decades, and often are forgotten as law enforcers and judges struggle to keep up with thousands of new warrants filed in courthouses across the nation each day.

An investigation by The Columbus Dispatch and GateHouse Media found more than 5.7 million cases in 27 states with open arrest warrants — enough to lock up every adult in West Virginia and Colorado combined. Add in the rest of the nation, and that number easily could double. Reporters sought records from all 50 states, but 23 did not provide usable data.

Among those warrants, reporters identified nearly 240,000 cases that involved violence, a weapon or sexual misconduct. That’s enough to fill every state prison cell in Texas, Michigan and Virginia.

There are at least 23,623 such criminal warrants just in Ohio's six largest counties.

When such warrants remain unserved, the violent suspects linger on the street, increasing the risk that someone else will be harmed, possibly killed. Law enforcement officials across the nation said it’s their biggest fear when they don’t have the resources to track everyone down.

The Dispatch also found that in Ohio, thousands of local warrants — including warrants for violent crimes — are not entered into statewide or national databases, meaning that even if an Ohio fugitive encounters police, officers might not know he or she is wanted.

“Most jurisdictions around the nation are doing nothing with warrants like this. Nothing,” said David Kennedy, professor of criminal justice at John Jay College of Criminal Justice in New York City and director of the college’s National Network for Safe Communities.

In central Ohio, police have never arrested a man they say bit off a woman’s nose. A man accused of orchestrating the gang rape of a woman while attacking her with a machete walks free. So does a drunken driver who police say slammed his car into another motorist at over 100 mph, killing the driver instantly.

Have a question about the series? Ask it in our Reddit AMA

Meanwhile, the warrants pile up. In Ohio’s six largest counties, about 92,000 warrants are more than 10 years old. If all of those people were arrested, those counties would fill their jails — ten times over.

“We shouldn’t be issuing all these warrants in the first place,”

Kennedy said. “We are over-enforcing and under-protecting. With the limited resources (law enforcers) have, the attention should be focused on violent crimes, and that’s not being done.”

Indeed, a Dispatch investigation found well over 1.2 million arrest warrants for offenses as minor as not paying a parking or traffic ticket or failing to obtain a dog license. Those warrants disproportionately affect people living in poor, minority communities and clog an already overwhelmed system.

Paths to a warrant

Many routes in the criminal justice system lead to an arrest warrant.

Authorities issue a warrant when they have evidence that someone committed a crime but haven’t yet located or arrested the suspect. Many people face warrants because they were charged with a crime, or even given a traffic ticket, but didn’t appear for a court date. Others were convicted but violated the terms of their probation.

Most people, especially those wanted for minor offenses, will remain free as long as they don’t cross paths with law enforcement in a jurisdiction that has access to their warrant. Often, it takes a routine traffic stop for the warrant to lead to an arrest.

“I could pull 17 officers out of schools right now to go out and try and serve all these warrants, but is that making our schools safer, our city safer?” said Columbus Police Chief Kim Jacobs. “If it’s a dangerous felon, OK, but the rest of them we have to consider our other priorities.”

Overall, the records collected by GateHouse Media showed one case with an open arrest warrant for every 32 people in the states that provided data. Among those with the most-complete records, Kentucky reported one warrant for every 16 people. In Michigan, where state police keep track of every warrant, there was one for every 10 people. Alabama reported one warrant for every six people.

Of the 27 states that provided records, several acknowledged that their records did not include thousands of warrants held at hundreds of local courthouses.

Five states didn’t provide information about charges reflected in the warrants, making it impossible to separate warrants for violent crimes from others in those states. Twenty-three either don’t consider warrants public records, don’t collect statewide information or wouldn’t provide data in a format that could be analyzed accurately.

Among the millions of dusty, forgotten warrants sitting in courthouses are individual tales of suspects on the run and victims who counted on authorities to bring people to justice — like the man in Oregon who police say killed a family friend over a few bucks, or the Minnesota man accused of drugging and raping a 13-year-old girl.

“We want to find these people and make sure we get justice for the victims,” said Sgt. Mike Norland of the Polk County sheriff’s office in Crookston, Minnesota. “But it gets a lot tougher to find new information when a warrant has been hanging out there for years.”

Waiting for justice

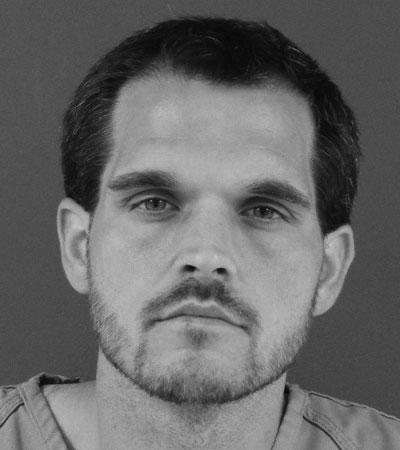

Diane and Steeg Hertz of Springfield, Ohio, have watched the video over and over. It shows a Dodge Charger accelerating to over 100 mph and then, inexplicably, its lights shut off. The Ohio Department of Transportation video footage from Interstate 70 goes dark, but the family knows what happened: Seconds later, that Charger rammed into the car driven by the Hertzes’ 37-year-old son, David, killing him.

Juan Ruiz, 21, fled on foot after the 2014 crash, but Columbus police soon arrested him at a relative’s home. He had no license, Social Security number or insurance and told detectives he was in the United States illegally. He scraped together $5,000 to pay a bail bondsman the 10 percent fee on his $50,000 bond and walked free. He jumped bail, and police believe he is now in Mexico. He’s wanted on a charge of aggravated vehicular homicide.

David Hertz graduated from Miami University and worked for 10 years as a computer technician for the Upper Arlington Public Library. He had just landed a similar job at the Delaware library shortly before he was killed. His parents say their shy son had transformed into a fun-loving free spirit the last eight months of his life.

The Hertzes compliment Columbus Police detectives for the attention they have given the case, but they want Ruiz found, convicted and put in prison.

“I would tell him he ripped a hole into our family,” said Steeg Hertz, 76. “We need to do everything we can to catch guys like this. I want Ruiz found more than anything before I die.”

It’s easy for open warrant cases to languish as new ones crop up, authorities say. Sometimes arrests follow a nudge — from a victim, an activist, a journalist — for a fugitive to be found.

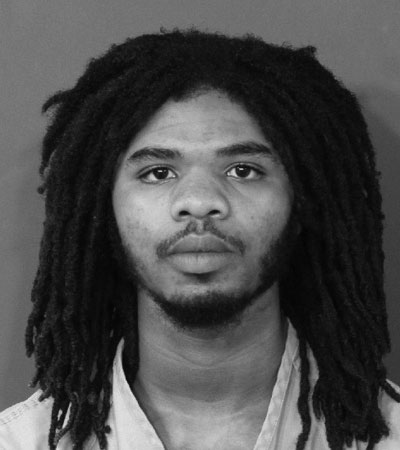

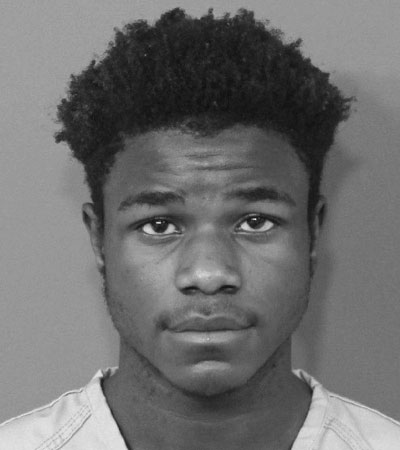

Leroy Lawrence was walking along a street in Anchorage, Alaska, on April 7, 2017, his 17th birthday. He was on his way to see a girl he liked when a stray bullet struck him in the face. Two men in a Chevrolet Monte Carlo had driven up close to where Lawrence was walking and started shooting at other men who had stepped out of an SUV.

The likable high school basketball player was revived in an ambulance and spent four days on life support before he died.

“My son was just an innocent bystander in a senseless drive-by shooting,” said an emotional Gene Lawrence, Leroy’s father. “Nothing is going to bring him back, but we wanted justice.”

Police immediately arrested one of the two accused of being the attackers, a 16-year-old. But 20-year-old Haitim Mahir Taha, the driver of the Monte Carlo, fled the scene, and ultimately the country. Authorities believed he was in Israel.

The murder warrant for Taha went unserved for more than 18 months before The Dispatch contacted Anchorage police in September to ask what was being done to find the suspect abroad. About two weeks later, Israeli authorities arrested Taha. He is expected to be extradited to Alaska to face charges in Lawrence’s death.

“I don’t know who you called or what you did to get this case moving, but thank you,” Gene Lawrence told The Dispatch. “I feel bad for everyone involved in this tragedy, but if you do something stupid like this, you should pay the consequences for it.”

Law enforcement officers across the nation said it’s especially difficult to make an arrest when a fugitive flees to another state or country, although authorities say they do their best to work with state and federal authorities to seek justice.

“The Leroy Lawrence case touched the hearts of our entire department,” said Anchorage Police Capt. Josh Nolder. “It’s not like we stopped looking, but it’s hard and very political when they leave the country. I just hope this brings some kind of closure for the family.”

Tough choices

Those responsible for serving warrants in central Ohio’s main law enforcement agencies often are drowning in other duties that take time away from tracking down offenders. And new cases, with fresher leads, come into police departments every day.

There are about 77 deputies, police officers or U.S. marshals who dedicate at least part of their day to serving warrants in central Ohio. That includes Columbus Police and Franklin County sheriff's office SWAT teams and the Southern District of Ohio U.S. Marshals Service.

3,000

open warrants in Franklin County involving violent crimes and weapons as of spring 2018

2,300

were for domestic violence or assault

139

were for rape and sexual assaults

16

were for murders

The marshals cover Franklin and 47 other counties.

“We visit some agencies and there will be cases and cases of files of open warrants, and there are literally cobwebs on them,” said Jim Cyphers, assistant chief for the U.S. Marshals Service, Southern Distirct of Ohio. “This is a huge problem everywhere. Law enforcement does its best to work together on these cases, but the reality is there are far more of the bad guys than there are of us.”

One case can consume days, weeks or longer.

Law enforcement agencies say they try to prioritize their cases, but it’s easy for some to fall through the cracks if the warrants aren’t served in the first few days or weeks. When judges issue bench warrants for probation violators or for those who failed to appear in court, police often don't know about it. Judges are buried under their own caseloads and rarely have time to pick up the phone to call detectives on individual cases.

Sean Mack, now a detective in the Columbus Police exploited-children unit, was part of the division’s now-defunct Enforcement Bureau, which until 2014 would sometimes conduct warrant sweeps. He started a practice that many officers now follow, requesting a daily email from the Franklin County Municipal Court listing open felony warrants in the ZIP codes he covered.

“I still get the list every morning at 6:30 a.m., like clockwork,” he said.

But, except for the SWAT team, which goes after only the most-dangerous armed suspects, there’s no dedicated warrant team. That’s what it would take to start cutting into the backlog, Mack said.

“You’d have to have a warrant squad dedicated, working those warrants every day,” he said. “Six to eight officers and maybe an analyst who could do research on the suspects you’re going after.”

Even warrants involving some attacks on police officers are not always priorities. The Dispatch found dozens of open felony warrants in Franklin County for people accused of assaulting officers.

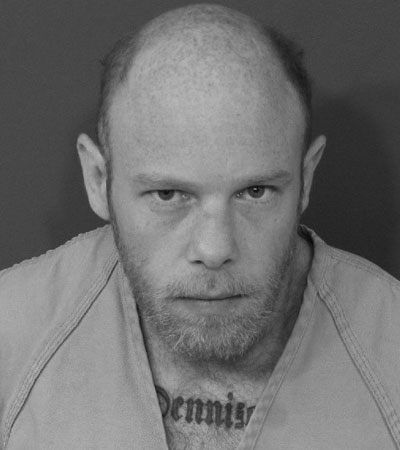

In 2002, then-Gahanna Police Chief Dennis Murphy stood on a woman’s porch, investigating a case of identity theft, when the woman spotted the suspect rifling through a neighbor's mailbox.

As Murphy ran for his police bicycle, the suspect got into his SUV and charged at the chief, who jumped out of the way. But the SUV smashed his bike.

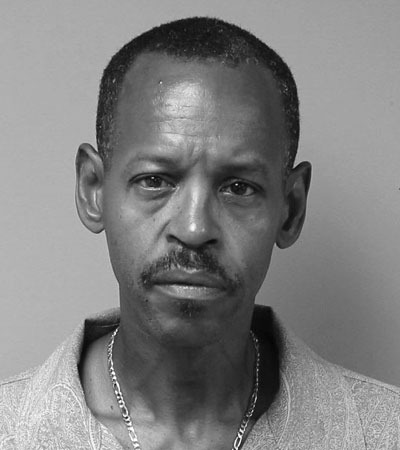

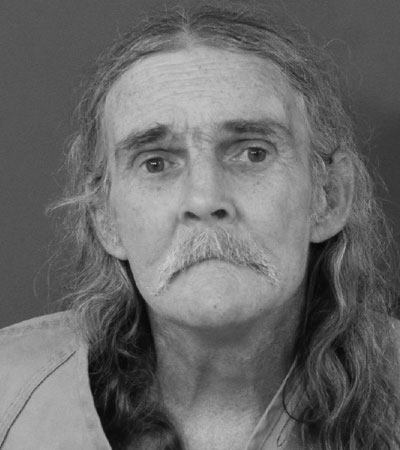

Other officers arrested Kamen Williams, now 54, who originally gave police a phony name. He was released on bond, and a grand jury indicted him on a charge of felonious assault. He failed to appear for an arraignment, and a judge issued a warrant.

Murphy said he didn’t want to divert resources away from other cases to go looking for Williams.

“If he had tried to hurt one of my guys, I would have hunted him down,” Murphy said. “You have to make these calls every day. I wish we could get them all."

Through the cracks

In some cases, victims have no idea that the suspects in their cases are running free.

Mariam El-Shamaa was attacked in 2002 by a man with a knife while she was serving on an academic-fraud committee at Ohio State University, where she was a graduate student.

Immediately after the panel found Weicheng “Mike” Yen guilty of cheating in a chemistry class, he pulled out a five-inch knife, walked up to the conference table and raised the knife above El-Shamaa. Two other committee members grabbed Yen before he could hurt her.

Ohio State police arrested Yen, then 20 years old. He was jailed but released while a grand jury considered felony charges. He was indicted on a felonious assault charge and an arrest warrant was issued, but it has remained unserved for the past 16 years.

Now a lawyer and mother of three living in Worthington, El-Shamaa, 40, doesn’t understand why Yen hasn’t faced justice. She admits she has been conflicted about the case over the years. After being contacted in 2010 by Yen’s attorney, she wrote a letter to prosecutors saying she wouldn’t oppose dropping the felony charge. But now she doesn’t believe the case should be dismissed.

Several attempts to reach Yen were unsuccessful. Authorities believe he has been living out of the country. When asked about Yen’s case, Lt. Mike Raven, head of SWAT for the Franklin County sheriff's office, speculated that the case fell through the cracks amid the thousands of warrants the office is tasked with serving.

"What if he'd been able to go through with the strike of that knife?” asked El-Shamaa. “I hope he eventually got the help he needed, but this isn’t something that should have been just let go."

Time is the enemy

It was supposed to be a fistfight to settle a dispute over money, but Arnulfo Beltran-Barboza brought a .38-caliber handgun and fatally shot a family friend, police say.

Beltran-Barboza threw the gun in some bushes and left Springfield, Oregon, just ahead of the police, who issued a statewide arrest warrant the same day: June 25, 2004.

Sgt. David Lewis, the lead detective, spent the next 48 hours on Beltran-Barboza’s trail. He missed catching the suspect by about an hour the first night. The next day, he figured out that someone drove the fugitive to Phoenix, and that he crossed into Mexico.

Beltran-Barboza remains wanted 14 years later.

“We were right on him for those first two days but were just a step behind the whole way,” Lewis said. “It’s very frustrating. We have made many more attempts to get him over the years, but the longer the case drags on, the tougher it gets.”

Law enforcement officers across the nation say they share Lewis’ frustration. They know the best window to catch a fugitive is within the first few days of the arrest warrant being filed.

“If we don’t get them within 72 hours,” said Lt. Paul Ohl, who leads the Columbus Police SWAT unit, “it gets tougher to get them.”

Judges, police, lawyers and reformers use words like "flood" and "fire hose" to describe the torrent of warrants from U.S. courts. At times, they say they feel helpless to keep up. Almost all agree that it’s vital to prioritize cases that represent the biggest threat to the public.

But that doesn’t always happen.

The Dispatch asked those in the local criminal justice system this question: Why not hold a meeting once or twice per year to review the same warrant data the newspaper compiled, pick the worst 50 to 100 cases and do everything in your power to find the bad guys?

Every person interviewed said that was a good idea and they would participate in such a meeting if someone organized it.

“We should be doing that right now,” said Chief Deputy Earl Smith of the Franklin County sheriff’s office. “What it boils down to is you can never throw enough resources at this. ... It is a waterfall that never shuts off.”

Do you like what you're reading?

Stories that inspire. Coverage that informs. Investigations that affect change. This is real news just when it's needed most. Subscribe today.