Is it time to overhaul the

cash-bond system?

ot long after making bail in his domestic violence case, a Licking County man fled Ohio and headed to Tennessee. There, he was accused of theft and disappeared again.

Columbus bail-bond agent Woody Fox got a tip that the man was in a small town in Nebraska.

“I load up two of my guys and we drive 17 hours to Nebraska,” recalled Fox, who was on the hook for the man’s $2,500 bail.

Fox and his men apprehended the absconder without incident and drove him back to the Licking County jail to face the misdemeanor charge of assaulting a girlfriend.

“Who else was going to bring him to justice?” Fox asked. “How else was he going to get punished for what he’d done to that young lady? The police weren’t going to go get him. They don’t have the manpower or the money.”

Efforts to overhaul Ohio’s bail system, which propose ending cash bail, could increase the number of defendants failing to appear in court, Fox said. Amid a movement that has taken hold in other states, bills have been introduced in both the Ohio House and Senate to reform cash bail but have yet to gain traction.

Failure to appear is the leading category under which warrants are issued.

For example, of the nearly 57,000 Franklin County Municipal Court arrest warrants that were active as of mid-February, more than 47,000 of them were issued because the person failed to show up for one or more court dates.

Bail is a system that exists primarily to ensure that those charged with crimes show up for future court dates. At the initial court appearance for defendants, a judge can release them on their own recognizance, with no bail required, or impose a bail amount that must be paid, often with the help of a bail-bond agent, to gain pretrial release.

Defendants who fail to appear for their court dates face the forfeiture of the bail amount. Similarly, bail-bond agents who cover a defendant’s bail are financially liable if the person jumps bail. The bail-bond agent has wide latitude, and a financial incentive, to pursue and apprehend the fugitive.

Private investigator Ted Owens puts on body armor while working with Woody Fox Bail Bonds.

Bail agent Woody Fox stands in the doorway of a home as agents search for Sheldon Curry, who skipped out on a $10,000 bond after being released on a drug charge.

Bail agent Woody Fox pounds on the door of a home he plans to search. Fox and other agents are looking for a suspect who failed to appear in court. Fox is responsible for the entire bail if a suspect doesn't show up.

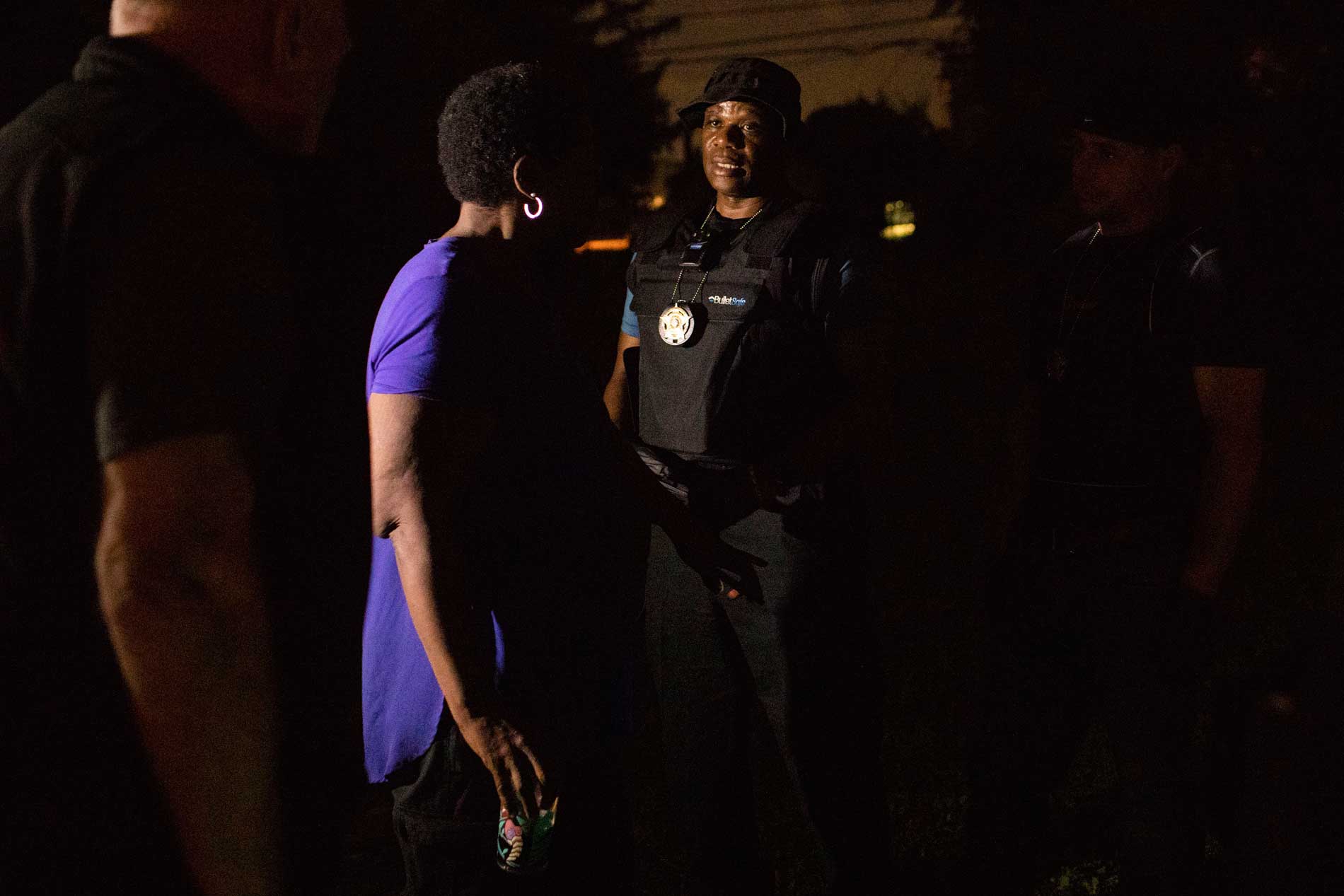

Bail agent Larry Garrett talks with a woman outside her residence as they search for Sheldon Curry, who skipped bond on a drug charge. Curry was recently seen at the woman's house, but wasn't there when agents came. Garrett has spent more than 100 hours tracking Curry.

In recent years, a growing chorus of criminal justice reformers have advocated for the elimination of cash bail. They argue that it discriminates against the poor, who may be confined in jail simply because they and their families can’t afford the bail. The practice also is criticized for needlessly contributing to jail overcrowding.

The bail-reform movement is so new that most court systems that have adopted it don’t have data about its effect on those who fail to appear.

In California, for example, the nation’s most sweeping reforms to eliminate cash bail just went into effect in October.

Even the state of New Jersey, which launched reforms that all but eliminated cash bail nearly two years ago, doesn’t have failure-to-appear statistics yet.

“By the end of the year, we should have solid numbers,” said Peter McAleer, spokesman for the New Jersey Courts.

When cash bail is eliminated, it is replaced by a risk-assessment tool that judges use to determine how likely a defendant is to re-offend or take off if released from jail. Based on that assessment — as well as a consideration of the seriousness of the charge — the judge decides whether the defendant will be released without bail, often under conditions that include periodic reporting to a pretrial services staff, or held until trial.

Hamilton County, Indiana, just north of Indianapolis, launched a pilot program in June 2016 that takes just such an approach to assessing defendants for pretrial release or detention.

Officials there are encouraged by the results of largely eliminating cash bail. In 2017, nearly 79 percent of 2,166 defendants in the county were released without bail. Of them, just 8.8 percent failed to show up for one or more of their court appearances, according to Stephanie Ruggles, the director of pretrial services.

While pleased with that statistic, Ruggles pointed out that no one can say with certainty whether the failure-to-appear numbers have improved because such data wasn’t tracked before the reforms were implemented.

“Anecdotally, our judges believe the the failure-to-appear rate has decreased,” she said.

The Hamilton County, Indiana, changes include much more stringent monitoring of those released without bail, she said. Pretrial services workers also send defendants text-message reminders five days and one day before their court dates. Studies have found that such notifications, not unlike those sent out to remind people of doctor or dentist appointments, reduce the number of people who fail to appear, Ruggles said.

“There are no studies that show that (cash bail) guarantees someone showing up for court,” she said.

Fox, at Woody Fox Bail Bonds, argues that common sense is all that’s necessary to realize the importance of cash bail. When a defendant’s friend or family member posts the necessary portion of bail to get Fox to post the bond, Fox requires them to sign a promisory note covering the full amount.

“They’ve got skin in the game,” he said. "When you let someone out of jail on scout’s honor — 'I'll be back' — there’s no skin in the game. The reason I go after them is, I’ve got skin in the game. ... If they get rid of us, they’re going to have a major problem.”

Do you like what you're reading?

Stories that inspire. Coverage that informs. Investigations that affect change. This is real news just when it's needed most. Subscribe today.