From All-State at Kathleen High School in Lakeland, to All-American at the University of Miami, to earning the right to be called one of the greatest middle linebackers to ever play in the NFL during 17 seasons with the Baltimore Ravens, there were a lot of boxes checked for the first Pro Football Hall of Fame selection from Polk County.

WORDS: Brady Fredericksen & Roy Fuoco

PHOTOS: Scott Wheeler

EDITS: Bob Heist & Andy Kuppers

AUDIO, VIDEO & WEB: Laura L. Davis

CHAPTER 2: In high school, Ray Lewis was a rare talent with a chip on his shoulder

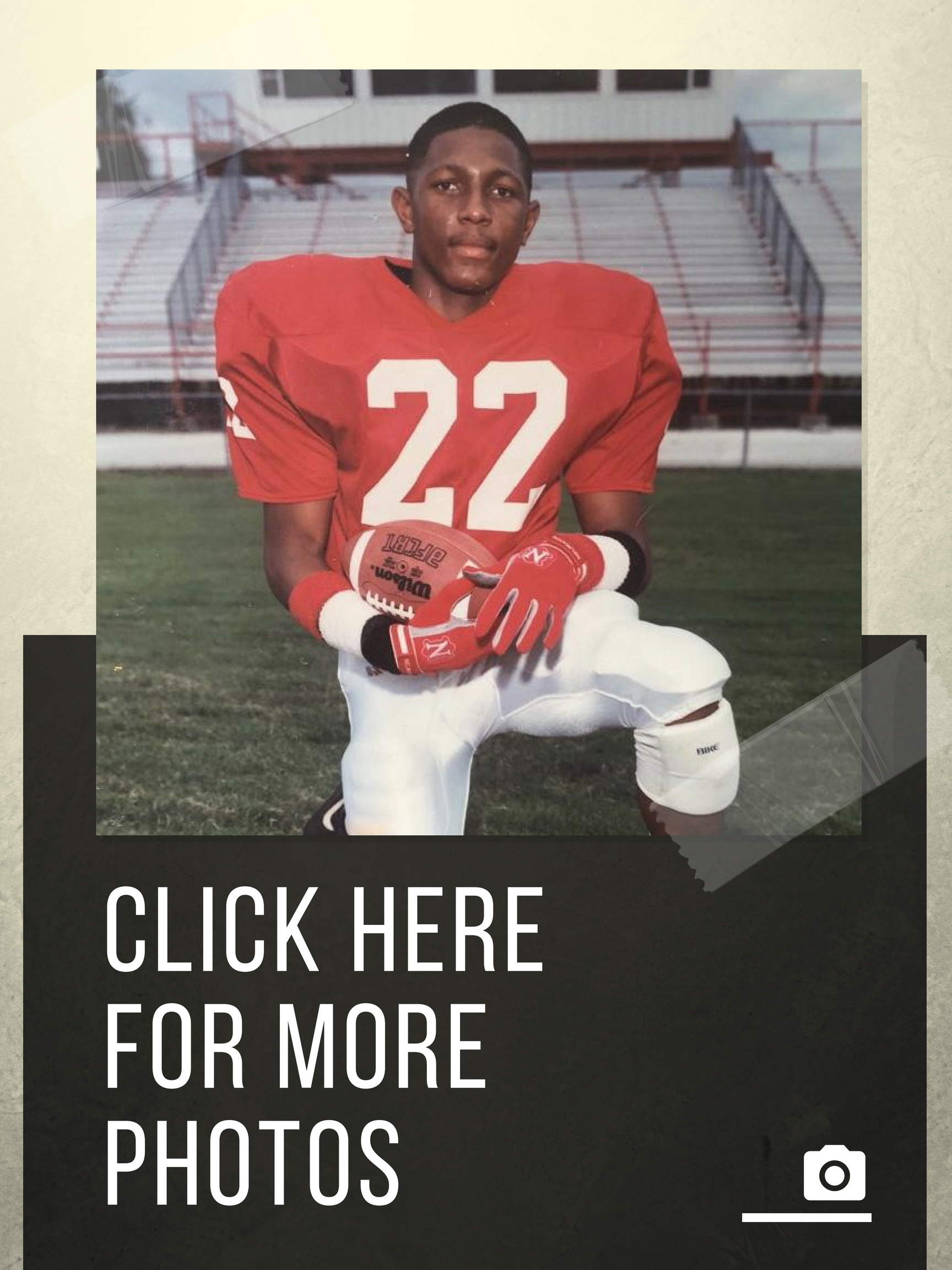

Ray Lewis was one of the top seniors in Polk County entering his final high school season in the fall of 1992.

The Kathleen star was highlighted on the cover of The Ledger’s football preview section along with Haines City’s Derrick Gibson and Lake Wales’ Melvin Pearsall. Gibson and Pearsall, however, were two-way players. Both were standouts at linebacker on defense and tight end on offense. Gibson would to finish third in the county in receiving yards and Pearsall would finish seventh by the end of the season.

Lewis? Well, he was in the process of convincing Kathleen head coach Ernest Joe to let him do more than just play linebacker.

“In his junior year, he played just on one side of the ball,” Joe said. “I came out of (Lakeland coach Bill) Castle’s camp, and Castle never really had kids go both ways. So I had that mindset. In the summer before his senior year, he sat down and talked to me and convinced me.”

So Lewis, in addition to playing linebacker, began returning kicks and punts and also playing some offense. Early on, it didn’t amount to much action in the backfield.

Lewis’ senior season changed in the third game, a 35-3 loss to Pearsall’s Highlanders. It was a game in which Kathleen lost wide receiver Travis Houston and running back Carlos McCalpin to broken legs.

Joe initially had quarterback Jason Mitchell run the ball more, to go along with his 120 passing yards, but Lewis convinced Joe to put him in at running back.

“I know the plays,” Lewis told Joe. “Twenty-eight toss, 29 toss, left, right — right?”

So Lewis began getting carries. His move to the backfield had no effect in that game against a Lake Wales team that was beginning a 28-quarter streak of not allowing a touchdown. But the move paid dividends as the season progressed, peaking in the season finale against Lakeland. He showed so much promise on offense that Florida coach Steve Spurrier recruited him as a running back.

By then, however, Lewis viewed himself as a linebacker, a position he wasn’t playing when he started his varsity football career as a sophomore, before Joe's arrival as head coach.

SOPHOMORE SENSATION

Lewis showed he wasn’t your ordinary football player nearly from the get-go of his sophomore season — at least to his teammates. He impressed on and off the field.

“It was just his work ethic,” said Irving Strickland, who went to Kathleen with Lewis and later coached the Red Devils. “His work ethic was the same then as it is now.”

Strickland was a senior when Lewis was a sophomore, and he was immediately was impressed with Lewis' athleticism.

“We were like, who is this dude,” Strickland said. “It was like, 'Wow!' What Ray does now, he was doing then — encouraging everyone, trying to get everyone better.”

Gary Lineberger remembers Lewis’ first year in high school. The former Kathleen athletic director was Lewis’ position coach that season.

“Initially, physically, he looked the part,” Lineberger said. “He was a sophomore coming out of junior high. He was 5-11, 6-foot, 185 pounds, so he looked the part. As we got into things, he had that football intelligence that we come to find out later, he picked things up quick, he was naturally aggressive and loved to practice.”

Former teammates and coaches are quick to note Lewis' love of practice.

“When you classify Ray, when you break it down, he always stood out,” Houston said. “His work ethic was like no other. He always stayed working out; he always stayed in the gym. He always studied the game of football because he loved the game of football.”

A fanatic at doing push-ups, Lewis was strong, and that helped him hold his own against seniors, boosting his confidence.

Grady Maddox, the Red Devils’ head coach that season, also gave Lewis confidence. An old-school coach who didn’t easily dish out praise, Maddox would often go to Lewis at the end of practice with words of encouragement and praise.

At the beginning of the 1990 season against Clewiston, starter William Campbell broke his jaw, and Maddox told Lewis he was going to start at strong safety.

Kathleen lost that game, but Lewis played well — about 22 or 23 tackles as he remembered.

There was a lot of losing that season; the Red Devils finished 1-9. Maddox was out as coach and Joe, who had been an assistant under Castle at Lakeland, was in.

“We were winning every game, but we just couldn’t finish it out,” Lewis recalled. “Being 1-9 taught me a lot. It taught me that I could be as great as I want to be, but if I want to really achieve team success, then I’m going to have to do more in buying into my team, teaching them why I do what I do, why I study the way I study, why I work the way I work.”

Lewis’ time at strong safety lasted just one year.

ENTER ERNEST JOE

Players often develop close relationships with their coaches. For Lewis, his coaches were the father figures in his life.

To his day, he calls Lineberger "Papa."

When Joe came over to Kathleen from Lakeland in the spring of 1991, Lewis formed a special bond with him.

“I took him home to his grandmother’s house where he was living and just told her I thought from what I’ve had the chance to see athletic-wise, if he continued to do well academically, he was going to have a football scholarship,” he said. “The relationship began there.”

Joe often had players over to his house — his wife made chili — and he remained part of Lewis’ life even after graduation. When Lewis was at the University of Miami, he often called Joe. Joe was there with Lewis on draft day, and he planned to be in Canton, Ohio, when Lewis was inducted into the Pro Football Hall of Fame.

Lewis always held coaches in high regard.

“I always treated my coach a certain way,” he said. “I always treated my coach with the ultimate respect. Mom installed something when I was young. She was so old-school. One thing she always talked to me about was respecting your elders. I would watch other players get into physical arguments with other coaches. I would be fearful to do that. There would be no way I could do that. That was the thing I think that carried over from high school all the way to the NFL.”

It took time for Joe to completely know what kind of player he had in Lewis — not in terms of ability, but in Lewis’ single-minded mentality of going all out, all the time.

Joe would run a seven-on-seven drill, an inside running drill with defensive linemen and linebackers and no defensive backs. The defense wasn’t supposed to tackle. Joe laughed as he recalled Lewis tackling the running back, despite being told no to go all out.

“I just had one speed, so I didn’t know what that meant,” Lewis said. “As a coach who ultimately became like a father figure to me, he understood me. He really got me.”

Lewis didn’t know any other way to play.

“I didn’t now you had a choice to take a break,” he said. “The choice for me was doing enough to go home, so when I got home, I could make not only myself proud but my family, my mom proud.”

Early in the relationship, Joe made a decision that impacted Lewis’ football future more than anything else. He moved Lewis from defensive back to linebacker, although Lewis and Joe differ in their accounts on how the move happened.

Joe remembered thinking in the spring that he needed help at linebacker and Lewis was the obvious choice. The Red Devils were getting ready to play Kissimmee Osceola in the spring jamboree, and that's when he made the move.

Lewis remembered moving to linebacker in the jamboree against Lake Gibson after teammate Jason Bamberger went down with an injury. Either way, once he began playing linebacker, Lewis was hooked.

“I came back to coach Joe and said, ‘I’m never going back to safety again. I’m too close to the ball,' ” Lewis said.

Lewis went on to make second-team All-County as a junior, as the Red Devils went 6-4. In the season finale, a loss to rival Lakeland, Lewis learned that two teammates, linebacker Steve Franklin and quarterback Jason Mitchell, were going to transfer to Lakeland. The stage was set for a memorable senior year.

THE FINAL SEASON

Polk County football was as strong as ever in the fall of 1992, particularly with a deep senior class. In addition to Lewis, Gibson and Pearsall, there were Auburndale running back/defensive back Victor Johnson, Winter Haven running back Demetric Denmark and Lakeland running back Dale Terrell.

Frostproof had running back Ernest Hamilton, who led the Bulldogs to the Class 2A state title in Faris Brannen’s last year as head coach and was the 2A player of the year and runner-up for Mr. Football.

Winter Haven was on the upswing under Dusty Triplett, Lake Wales was on its way to a 10-0 regular-season record under Rod Shafer, Haines City was coming off a state runner-up finish under Danny Green. And Lakeland, as always, was a team to be reckoned with under Castle.

And Kathleen? All the Red Devils did that year under Joe was have their best season since record-setting quarterback David Bowden led Tom Atwell’s 1970 squad to a 10-2 record.

Lewis, at linebacker, was at the forefront, and he was a marvel to watch on the field.

“He could go from sideline to sideline better than anyone I’ve been around,” Joe said. “He’s up in the hole just like that on a blitz, just have a 100 mph motor. He never slowed down. You never had to tell him to hustle or pick his feet up. It’s just wide open.”

Kathleen got off to a 2-1 start with the loss coming to Lake Wales in a 35-3 drubbing. Shafer found early in that game not to run wide. The first time the Highlanders tried a quick pitch, Lewis was all over the ballcarrier.

“He was a great athlete,” Shafer said. “We didn’t run one play where we didn’t know where he was. You had to scheme for him because he was just really dominant. Football is a little different than basketball. You need more than that one player.”

Shafer ran the inside veer and outside veer with Pearsall and usually a second player to prevent Lewis from dominating defensively.

That game turned out to be just a blip in the regular season for the Red Devils, and it was a turning point as Lewis’ role on offense progressively grew.

As a running back, Lewis ran 10 times for 53 yards in the first three games, 18 times for 172 yards in the next three, and 34 times for 204 yards in the next three before finishing the regular season with 115 yards on 15 carries against Lakeland.

Against Winter Haven, Lewis’ Uncle Curtis shaved Denmark’s name in Lewis' head. Lewis had a 59-yard punt return, rushed for more than 100 yards and had more than 10 solo tackles. The Red Devils won 15-14.

It was after that game when Lewis went to Joe and asked to run the ball earlier in games when his legs were fresh. In the next game against Haines City, they ran a trap on the first play, and Lewis ran about 81 yards for a touchdown.

“Is he coachable? Yeah,” Joe said. “Can he tell you that he can move this Ledger building? You better believe it, or he’s going to die trying. After that game, I already was sold on him. Anytime he came off the field defensively, he stood next to me and said I’m ready to go. He was that much of an impact.”

One of the most memorable games — other than Lakeland — was a 24-21 win over Bartow. Kathleen trailed 13-0 at halftime when the players convinced Joe to go to the Big Bone, a wishbone formation with 263-pound nose guard Tommy Lane at fullback, the 230-pound Franklin at right halfback and Lewis at left halfback.

On the first drive in that formation, Lewis scampered down the right sideline for a big gain that set up Ken Bridges’ touchdown. Lewis then scored on runs of 3 and 33 yards.

“They got some momentum on that first drive when they went to it, turned right around, stopped us, got the ball back and went right back to it, and we did not respond,” said current Winter Haven coach Charlie Tate, who was Bartow’s head coach in ’92. “It really was because of the momentum swing and that formation and that physicality. ... It solely was because of his want-to and how it spread to the other players.”

It was against Bartow when Lewis knew his future was at linebacker. Early in the game, he bobbled a kickoff and was hit hard by a Bartow defender, dazing Lewis for about three minutes.

“I’m telling you, that dude from Bartow changed my life forever,” Lewis said.

The high point of the season came against Lakeland. The game was played at Kathleen, and Lewis was ready.

“That night, I said there’s no way they win, not tonight,” he recalled. “It was a big night for me.”

Lewis set the tone and scored the first touchdown on an 8-yard run. Kathleen went on to win 36-14.

“They were a really good team that year,” Castle said. “Throughout his career, the time I was really impressed with him was that game. He played tailback and he played linebacker. He was a heck of a high school running back to tell you the truth. He was one of those rare talents.”

Kathleen finished the regular season with its first district title since 1988. The Red Devils won their first playoff game with Lewis scoring the only touchdown in a 6-0 victory over Boca Ciega.

It came to an end against Fort Myers. Joe knew that Fort Myers was focusing heavily on Lewis. So on the first play of the game, the Red Devils faked a reverse to Lewis. With all the defenders flowing toward Lewis, Bridges ran down the right sideline for a touchdown.

That was the high point of the game for Kathleen. Fort Myers beat the Red Devils 35-7, and Lewis’ high school football career was over.

Lewis was both a first-team All-County and All-State selection. But Gibson was named player of the year and the FACA district MVP, and he also was selected to the Florida-Georgia game to the chagrin of Joe.

“We sat in the room and he was a little disappointed. But I told him, don’t worry about it, great things are going to come,” Joe said. “He shook it off. He always had a chip on the shoulder. I’ll show you.”

And so he did.

In high school, he was more than a football player

Ray Lewis was more than a football player in high school. Away from the athletic arena, he was in ROTC. But perhaps his greatest individual success came on the wrestling mat.

The Pro Football Hall of Fame linebacker ended his athletic career at Kathleen High School by winning a state championship at 189 pounds over Lyman’s Dallas Simpson at The Lakeland Center.

Lewis’ reaction?

“It was more of relief,” said Steve Poole, who was Kathleen’s wrestling coach at the time. “It was a tough match. He was exhausted. I was more excited than he was.”

Lewis took a roundabout route to the wrestling mat. It began when he walked out of the gym after being called for a hard foul while playing basketball in the ninth grade. Upon leaving the gym, he ran into Poole, who took him to the cafeteria where wrestling practice was being held. Poole tried to get Lewis interested in wrestling, but at the time, wrestling wasn’t for him.

By the time Lewis got to Kathleen, his cousin Marius Franklin convinced him to go out for wrestling. Initially, Lewis was raw technically, but his strength and athleticism allowed him to be successful.

“Honestly, I figured out the science to wrestling very quickly,” he said. “You beat the man in front of you. I was really good at that because I was really stronger than a bunch of the kids my age. I give all the credit to all the push-ups and sit-ups I did.”

By the time Lewis got to the state tournament as a sophomore, the lack of technical skills caught up with him. He lost to a more experienced wrestler and finished fourth in the state.

Poole became head coach of the varsity wrestling team at Kathleen when Lewis was a junior. Lewis told Poole he wanted to be the best ever at Kathleen and break the records set by Ray Jackson, his father, in the 1970s.

“Basically, it was hard work,” Poole said. “There were other kids out there just as strong. The two things that helped him was he worked hard, and he had a great heart.”

Again, Lewis’ work ethic paid off, as he came early and stayed late.

“Oh my gosh, (Poole) would wrestle anybody and beat any of us,” Lewis said. “He was so good at technique. He was a master of technique and counter attacks. And he gave me that. It changed my entire life.”

Poole found Lewis a joy to coach.

“Personality — he was a funny kid,” Poole said. “He motivated kids. He would push them. He had a great sense of humor, a great laugh. He liked to make the team smile and laugh.”

Lewis had a great rivalry in high school with Auburndale’s Victor Johnson.

“It was a huge rivalry,” said Bob Hartley, who was Auburndale’s wrestling coach. “Victor was about as strong as he was. They were both very physical wrestlers. We just had to use the best technique as we could. We wanted to try to take him to the last period because we thought we were in better wrestling shape.”

When they were juniors, Lewis pulled out a late win in the 189-pound final at the county meet to beat Johnson 7-6. As seniors, Johnson got revenge with an 8-6 win.

“All their matches came down to the wire,” Hartley said. “The only good thing was that they were in two different districts.”

That meant both wrestlers could take aim at a state title. Johnson, who was state 3A runner-up as a sophomore, won back-to-back state championships as a junior and senior.

Lewis dropped an 8-5 decision to Miami Columbus’ John Acona in the 4A final as a junior.

“He wanted to be a state champion," Poole said. "He wanted to outdo his dad. So he worked at it.”

One year later, he beat Simpson 11-8 in the title match to finally become state champion.