From All-State at Kathleen High School in Lakeland, to All-American at the University of Miami, to earning the right to be called one of the greatest middle linebackers to ever play in the NFL during 17 seasons with the Baltimore Ravens, there were a lot of boxes checked for the first Pro Football Hall of Fame selection from Polk County.

WORDS: Brady Fredericksen & Roy Fuoco

PHOTOS: Scott Wheeler

EDITS: Bob Heist & Andy Kuppers

AUDIO, VIDEO & WEB: Laura L. Davis

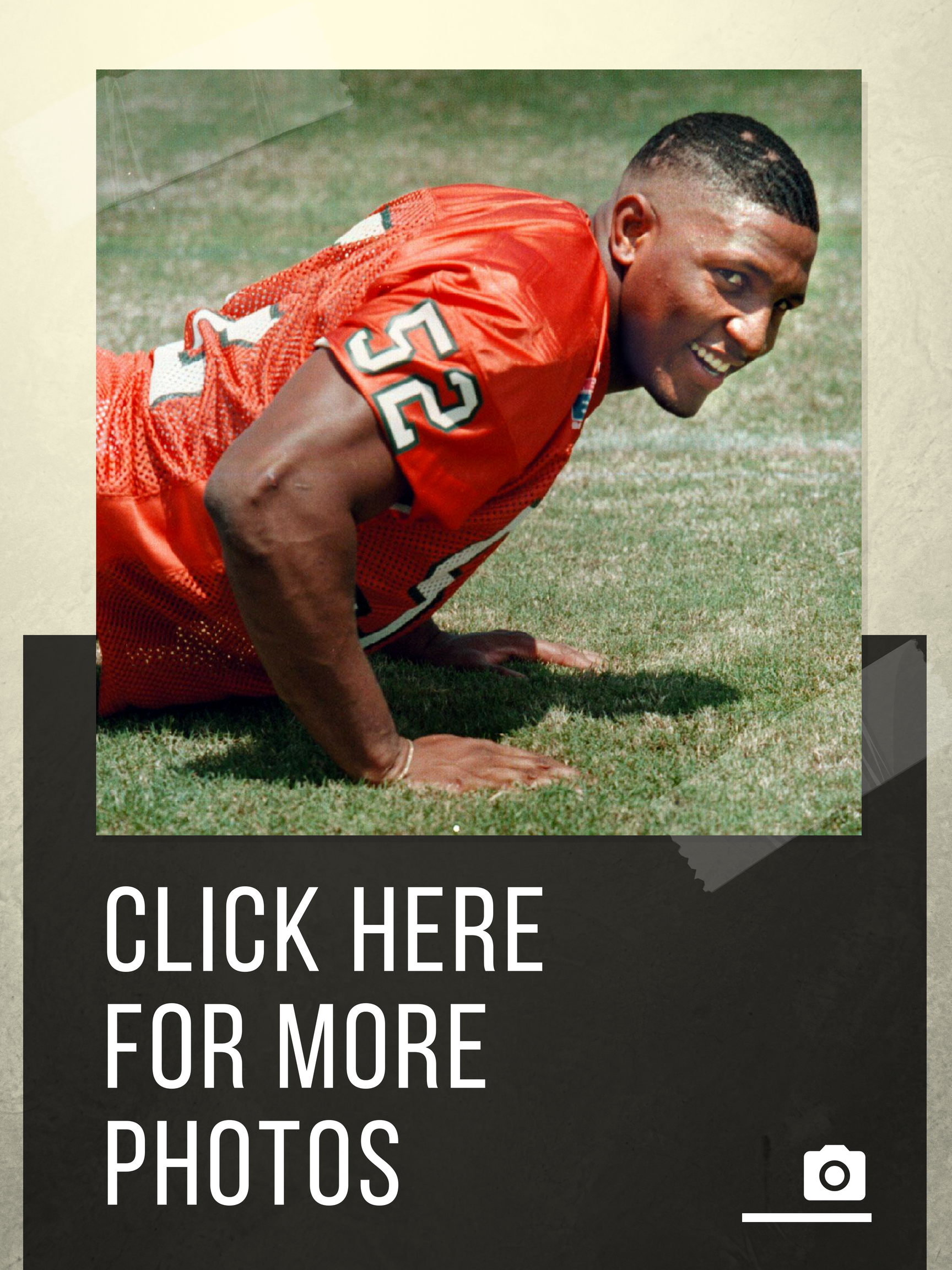

CHAPTER 3: Ray Lewis shined on a team full of stars at The U

America was introduced to Ray Lewis on Sept. 25, 1993.

The University of Miami arrived at Folsom Field in Boulder, Colorado, ranked third in the nation.

Though starting middle linebacker Robert Bass went down with a knee injury one week earlier against Virginia Tech, the unbeaten Hurricanes quickly discovered a capable replacement in Lewis. The freshman from Kathleen came off the bench to make 12 tackles against the Hokies.

His performance against No. 13 Colorado was even better. Lewis piled up 17 tackles as Miami jumped out to a big lead before holding off a late Kordell Stewart drive to win 35-29. He was the Chevy Player of the Game.

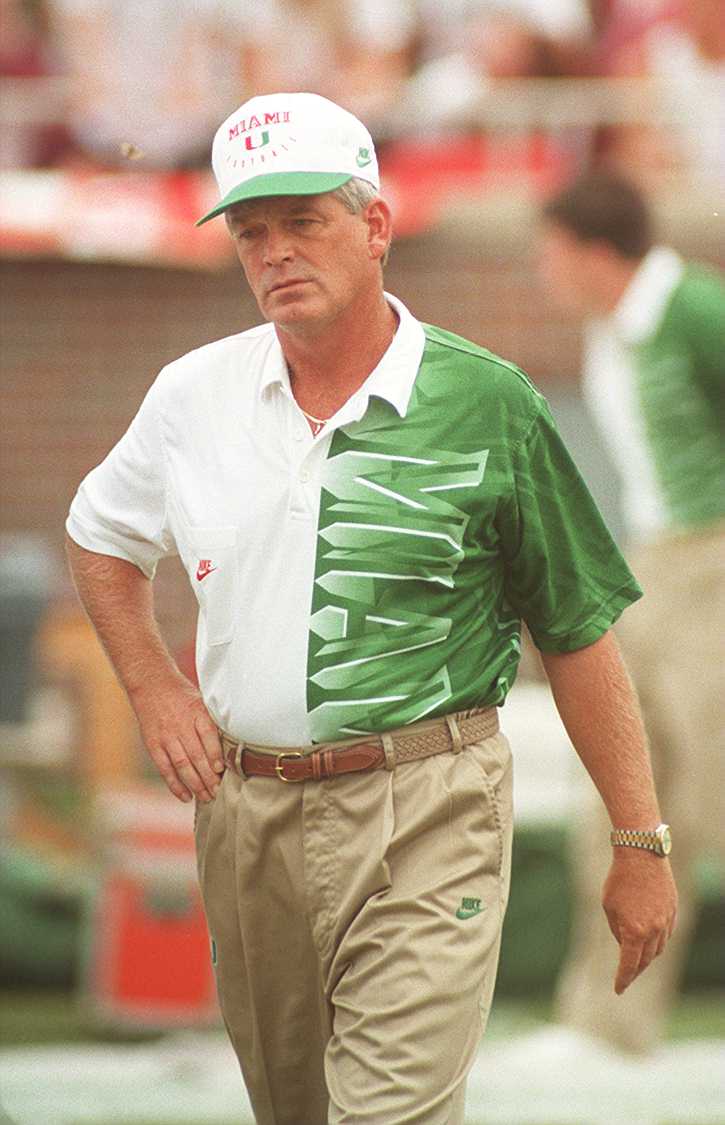

“He was all over the field,” said former Miami head coach Dennis Erickson. “There are some guys, sometimes, when the game starts, they just go to a different level. He had that attitude. That’s how he practiced, and he was special.”

Lewis' former high school coach, Ernest Joe, watched the game from a sports bar in Tampa.

He was taking a lunch break while studying for his master’s degree. He had seen Lewis dominate plenty over the years, but this was different. By the time he left — letting everyone at the restaurant know he coached Lewis — he knew his student would make it.

“I said the sky is the limit,” Joe said. “He won’t have to worry about a rotation when this guy (Bass) comes back. To get 17 solo (tackles) as a freshman like that; he can play on that next level playing like that.”

Lewis remembers walking off the field. He spoke to a reporter who asked him how good he thought he could be.

“I said, ‘Honestly, by the time I walk up out of here, I may be the greatest player to ever walk out of the University of Miami,' ” Lewis said. “I wasn’t necessarily saying I was better than anybody else. It was me saying, ‘I think I’m willing to work to be great just like these guys who are great.’

“When the time came up and my number was called, I was ready for that challenge. I think the coaches saw enough of my ability to say we can trust him.”

COMING IN LATE

When Lewis left Lakeland for Coral Gables late that summer, he wasn’t worried about his number or his place on the team. He was just worried about getting to camp in time. After passing his SAT late in the summer, Miami brought him down four days before training camp.

Lewis packed up a bag and crammed into his grandmother’s white Cadillac.

“We pulled up at college and she dropped me off,” he said. “I was like, 'Look, I will survive. We’re good.'”

Once he got acclimated, his focus changed.

Lewis wanted to be on the field. He knew he was good enough to be on the field, but avoiding a redshirt year as a freshman was no small task in 1993. Pete Garcia, a longtime football staffer at Miami, told Lewis early in camp that he wouldn’t be in the media guide or program this season.

You signed late and probably won’t play much, Garcia told Lewis. People don’t know who you are, he said.

You’ll be in it next year, he said.

That lit a fire.

When it came time to pick uniforms, Lewis had worn No. 22 in high school. Randy Shannon, then the Hurricanes’ linebackers coach, didn’t like his guys in weird numbers. Rohan Marley was the last backer to get a single-digit uniform.

Lewis suggested 52 because five and two combines to be seven, which is deemed a holy number in Christianity. Faith had always been a significant part of life for Lewis, and Shannon liked that.

He never wore another number in his football career.

“He was good from the time he stepped onto the field,” former Miami defensive coordinator Greg McMackin said. “He had a great football feeling. He’s the most aggressive player that I’ve ever coached — that includes the NFL and all the Miami kids. He was just very aggressive.”

That aggression manifested early at Miami. Twan Russell, a linebacker who arrived at Miami one year before Lewis, remembers camp in 1993. The boisterous freshman from Lakeland was quiet.

“He came in initially and people won’t believe that he didn’t say a lot the first day,” said Russell, who played with Lewis from 1993 to 1995. “But day two and three, he began to speak with his play. You began to see very quickly he was something special.”

Lewis took a liking to a sophomore defensive tackle named Warren Sapp. Lewis wanted to impress Sapp, who would grow into a dominant force during the next two seasons before leaving for a hall of fame NFL career with the Tampa Bay Buccaneers and Oakland Raiders.

“First day of 9-on-7s, James Stewart runs a sweep toss and I’m in there with the ones,” Lewis said. “I shoot through the gap and I hit Big Stew. Sapp and everybody stormed the field. They were like, ‘Oh my gosh, what is this we got on our hands?’ ”

Shannon tried to work Lewis at outside linebacker but, even as a freshman, he resisted.

He was a middle linebacker. He was a play caller. He was the quarterback of the defense.

Lewis made it a point to endear himself to the team’s leaders like Marley and Sapp. Sometimes that endearment came in the form of challenging them on the field, but Lewis’ competitiveness in practice is what caught the eye of his coaches.

“He had that mentality at a young age,” Erickson said. “He knew what he wanted to do, and it was just natural for him. You’ve got to understand, when he came to Miami — for him to come and play as a freshman — that is quite an accomplishment at that school. He was a leader from the beginning.”

THE SEMINOLES

The Miami-Florida State rivalry dates to 1951.

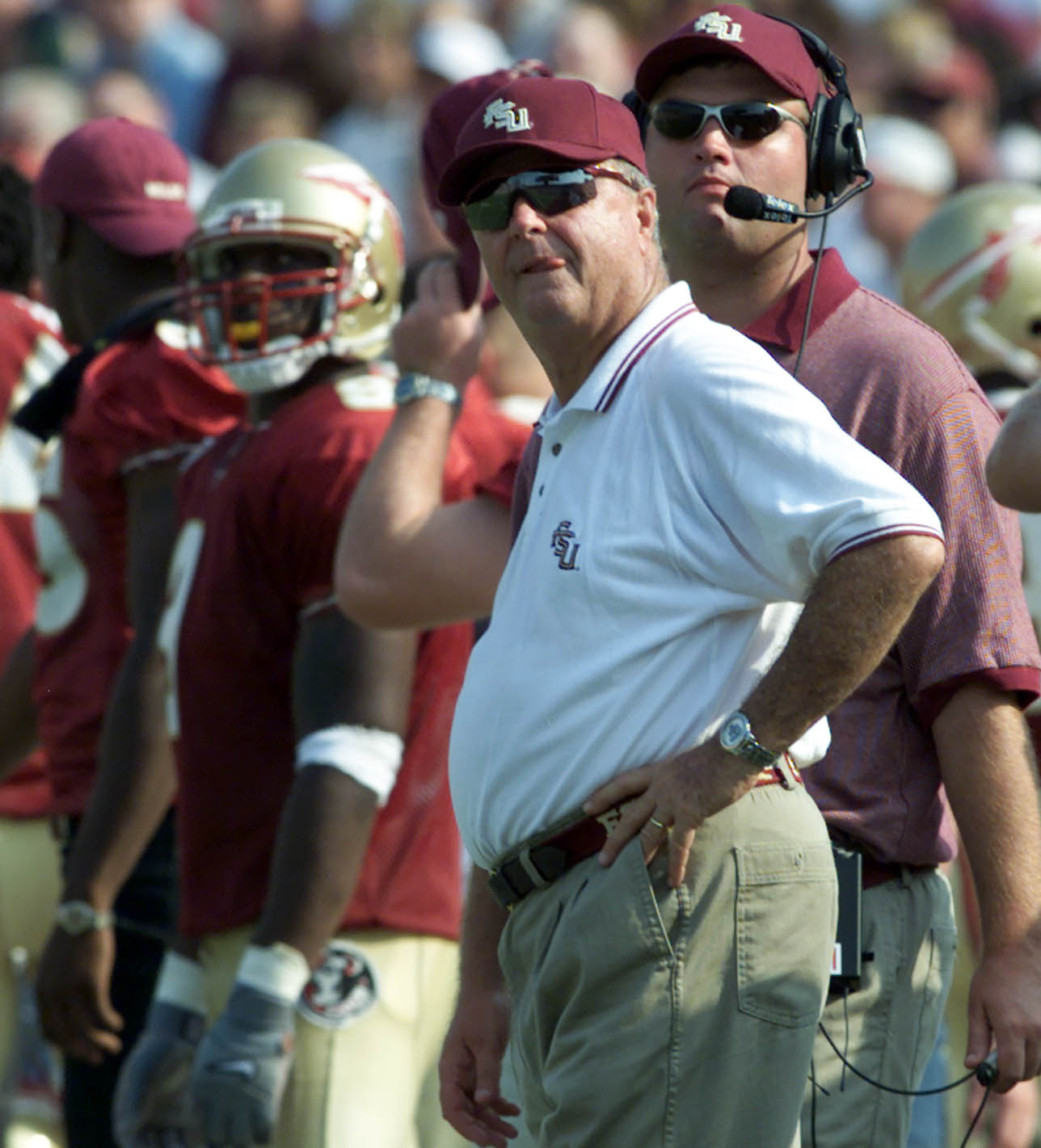

It existed before Lewis was born, but it was personal for him. Lewis was recruited by Bobby Bowden at Florida State. It didn’t work out. The first matchup in 1993 wasn’t particularly close, as Charlie Ward and FSU rolled Miami 28-10.

“You walk into Doak Campbell and you’re like 'This is intense — this is really intense,' ” said Lewis, who had 11 tackles in the loss. “It meant more when I finally got them in the Orange Bowl.”

That came in 1994.

Lewis remembers a conversation with Sapp. They talked about how the game was circled on the calendar and how badly they wanted to move past the 18-point thumping.

“That sophomore year really clued me in to how serious the rivalry really was,” Lewis said. “I was like, ‘Man, that taste last year, Sapp, no way. That ain’t happening ever again.’ ”

Teammate Trent Jones asked Lewis the week before the game what was on his mind.

“Bro, I’ve been waiting to get to this point where I can play them on my terms,” Lewis said. “I went to Sapp and them and they all knew the story. They all knew how I felt about it.

“It was a personal thing for me — every year.”

The Hurricanes beat Florida State 34-20 that season. Lewis collected 12 tackles in the win, but it was Sapp’s game. The eccentric tackle came away with seven tackles, 2.5 quarterback pressures and 1.5 sacks for a defense that grew into one of the most dominant units in school history.

Miami finished the year 10-2 thanks to the No. 1 total defense in the country.

The unit gave up just 220.9 yards per game. They boasted the No. 7 rushing defense — allowing just 96.8 yards per game — and the top passing defense, giving up just 124 yards per game, while picking off 18 passes. The Hurricanes allowed just nine offensive touchdowns all season.

They went on to play for the national title, losing to Nebraska 24-17 in the Orange Bowl.

“I will put that ’94 defense, seriously, statistically, up against any defense ever in college football,” said Lewis, who led the team with 152 tackles. “It was a very, very dominant group of men.”

Lewis never played in a close game against Florida State. The Seminoles avenged that 1994 loss with a 41-17 win the following year. They wouldn’t lose to the Hurricanes again until 2000.

“He’s one of the best we played against,” Bowden said of Lewis. “I coached 47 years, and he was one of the best that I ever played against. He was just a great football player.

“You try to study them and find out where they’re going to be. Does he line up on the right or the left? Ray lined up in the middle. He could get to everybody. He had great speed and a healthy, big, strong body — once he got to you, he could hit you pretty good.”

THE SEMINOLES

The Miami-Florida State rivalry dates to 1951.

It existed before Lewis was born, but it was personal for him. Lewis was recruited by Bobby Bowden at Florida State. It didn’t work out. The first matchup in 1993 wasn’t particularly close, as Charlie Ward and FSU rolled Miami 28-10.

“You walk into Doak Campbell and you’re like 'This is intense — this is really intense,' ” said Lewis, who had 11 tackles in the loss. “It meant more when I finally got them in the Orange Bowl.”

That came in 1994.

Lewis remembers a conversation with Sapp. They talked about how the game was circled on the calendar and how badly they wanted to move past the 18-point thumping.

“That sophomore year really clued me in to how serious the rivalry really was,” Lewis said. “I was like, ‘Man, that taste last year, Sapp, no way. That ain’t happening ever again.’ ”

Teammate Trent Jones asked Lewis the week before the game what was on his mind.

“Bro, I’ve been waiting to get to this point where I can play them on my terms,” Lewis said. “I went to Sapp and them and they all knew the story. They all knew how I felt about it.

“It was a personal thing for me — every year.”

The Hurricanes beat Florida State 34-20 that season. Lewis collected 12 tackles in the win, but it was Sapp’s game. The eccentric tackle came away with seven tackles, 2.5 quarterback pressures and 1.5 sacks for a defense that grew into one of the most dominant units in school history.

Miami finished the year 10-2 thanks to the No. 1 total defense in the country.

The unit gave up just 220.9 yards per game. They boasted the No. 7 rushing defense — allowing just 96.8 yards per game — and the top passing defense, giving up just 124 yards per game, while picking off 18 passes. The Hurricanes allowed just nine offensive touchdowns all season.

They went on to play for the national title, losing to Nebraska 24-17 in the Orange Bowl.

“I will put that ’94 defense, seriously, statistically, up against any defense ever in college football,” said Lewis, who led the team with 152 tackles. “It was a very, very dominant group of men.”

Lewis never played in a close game against Florida State. The Seminoles avenged that 1994 loss with a 41-17 win the following year. They wouldn’t lose to the Hurricanes again until 2000.

“He’s one of the best we played against,” Bowden said of Lewis. “I coached 47 years, and he was one of the best that I ever played against. He was just a great football player.

“You try to study them and find out where they’re going to be. Does he line up on the right or the left? Ray lined up in the middle. He could get to everybody. He had great speed and a healthy, big, strong body — once he got to you, he could hit you pretty good.”

So, why wasn't Ray Lewis a Seminole?

Ernest Joe always brought his teams up to Tallahassee.

Each summer before fall camp, the Kathleen football coach would gather his Red Devils and head nearly five hours north to Florida State. Joe liked going to Bobby Bowden’s summer camp because it was a good experience for the kids.

Bowden was always good to the coaches, too. He invited them up to the offices to mingle with the FSU staff. They would talk shop and go over film long after the players had gone to bed. If you had a prospect of interest, you probably got some facetime with Bowden.

And in 1993, Joe had a player like that: Ray Lewis.

“Wally Burnham was our assistant coach who recruited him,” Bowden said. “I remember talking about him and how much we wanted him.”

The feeling was mutual.

Lewis, who eventually became one of the greatest linebackers in college football history at Miami, didn't grow up watching the Hurricanes. He watched Florida State every Saturday.

He loved Seminoles linebacker Kirk Carruthers. His cousin, Lakeland grad Shannon Baker, played receiver for Florida State. During Lewis' teenage years from 1987 to 1993, Florida State never lost more than two games in a season.

They weren’t just cool; they were good.

“Kirk Carruthers, oh my gosh,” Lewis said. “Kirk used to do this little dance after he made a big play; he used to kick his knee up. I was such a huge fan of Florida State.”

This story, of course, does not end with Lewis in Tallahassee.

Florida was never an option. Steve Spurrier wanted him as a tailback. Lewis, by then, knew he was a linebacker.

Before he ever took a recruiting visit to Florida State, he made his way to Auburn and Florida A&M.

“I took a trip to Auburn, but they were so interested in (former Haines City star) Derrick Gibson that it didn’t matter about me,” he said. “They took him in one room and separated us. I was like, ‘Ok, I guess they’ve got their thing.' ”

Lewis knew Florida State. He went to camp there. He had family there.

He met with defensive coordinator Chuck Amato when he finally visited. Bowden popped in to say hello and warm Lewis up. Amato eventually brought Lewis back into another room and they got down to football.

“We like you,” Amato said. “We think you’re a great athlete. We really want you here as a Florida State Seminole.”

Amato talked about the team. He talked about another linebacker they had named Derrick Brooks, who went on to star in the NFL for the Tampa Bay Buccaneers before being enshrined in the Pro Football Hall of Fame in 2014. Amato said the plan would be to bring Lewis along slowly. They wanted him to play behind Brooks at middle linebacker.

“Looking at your size, you’re a little small right now,” Amato said. “But in two years, we’ll put some size on you. You’ll be ready to play by your junior year.”

That wasn’t in Lewis’ plans.

“I just stood up, shook his hand and said, ‘Coach, thank you, but no thank you',” Lewis said. “ ‘How do you know I’m not better than Derrick Brooks right now?’ I went to Ken Alexander, he was my host. I remember going back to his apartment. Shannon was there.

“I was like, 'Can I please get a plane ticket out of here. I want to be out of here. I want to go home.' ”

Bowden doesn’t remember it like that.

“These boys that take visits to colleges, they visit to see if they feel good there or not,” Bowden said. “It was probably something he didn’t like. He didn’t feel comfortable.”

Florida State remained interested after signing day. With one scholarship left that spring, the staff told Lewis and, coincidentally, Lake Wales’ tight end Melvin Pearsall, that they just had to pass their SAT.

Pearsall passed first and got the scholarship.

“He loved Florida State,” Joe said. “Every year he went to that (FSU) camp in the summer. That was his mindset, where he wanted to go, and it didn’t happen.”

That left Lewis and Joe in a desperate situation. They had no options. Joe talked about the possibility of playing a few years at a junior college in Mississippi. Lewis thought, if they couldn’t find a bigger offer, that he would just play at Florida A&M.

Miami had kept an eye on Lewis since his final high school game. The Hurricanes had a spot.

Lewis remembers coming home to his grandmother, Elease McKinney, one day late that summer. An envelope sat on the table and she told him to open it. It was his SAT results. He passed on his fifth and final try with a combined score of 710.

The Hurricanes were waiting.

“We knew he was going to pass it, so we stayed with him,” said former Miami head coach Dennis Erickson. “Attitude-wise, he fit into what we were doing.

“His attitude in those days: He was a Miami-type guy.”