It was a cool, sunny Thursday morning in January 2012.

Christy Collins appeared in a wood-paneled courtroom on the ground floor of the newly built Antelope Valley Superior Courthouse. The 34-year-old Navy veteran faced three criminal charges stemming from her midwifery practice.

For months, she had solicited business under the name Gentle Birth Midwifery and provided a host of services in the high desert north of Los Angeles without a state license or direct supervision, court records show.

The California Board of Medicine caught her and provided its findings to the local district attorney, who filed the charges.

Facing Los Angeles Superior Court Judge Christopher Estes, Collins entered a plea deal: no contest to a misdemeanor charge of unlawful midwifing, and not guilty to two felonies — practicing medicine without a license and theft by false pretense.

Estes sentenced her to three years’ probation and ordered her to pay $9,856, of which $1,500 would go to a former client named Joann Krause. The medical board would get the rest.

Collins escaped serious punishment. Had the court convicted her of the felonies, she could have spent six years in prison and paid an additional $10,000.

“It was a traumatizing situation,” Collins told GateHouse Media. “It had nothing to do with an injured baby or injured mom. It was about blood pressure.”

Collins told GateHouse Media her only crimes were taking Krause’s blood pressure once while serving as her doula, and removing the word “student” from her website after applying for — but before receiving — her state license.

But Krause said Collins provided months of prenatal care — taking her blood pressure, checking her cervix, monitoring her baby’s heart rate — and that she was prepared to deliver Krause’s baby in an inflatable pool she brought to the family’s home in February 2011. When Krause decided to deliver at the hospital instead, Collins accompanied her as a doula.

Krause knew Collins was a student midwife and that she was under supervision by licensed midwife Karen Baker. California requires supervisory midwives to be physically present at all times client services are provided, but Baker never came to any of the appointments, Krause said.

Baker confirmed Collins practiced under her as a student, but the two lived far away from each other and they rarely saw each other in person.

“I do not have enough experience with Christy to know if she was a great midwife,” Baker said.

Less than two weeks after her plea deal, Collins complained about the injustice of her “rotten circumstances” in an online campaign to cover her court costs. Ninety-two people raised $7,178. Many left comments, such as, “let us end the witch hunt” and “I hope you don’t have to pay that woman a dime,” referring to Krause.

Danielle Yeager knew none of this. The 28-year-old Las Vegas casino worker was struggling with her own rotten circumstances. Doctors diagnosed her with stage 1 cervical cancer and told her she might never get pregnant.

Sixteen months later, Yeager did get pregnant. And she hired Collins as her midwife. Six months after that, Yeager’s baby died.

Yeager initially didn’t want a midwife or a home birth. She wanted an obstetrician who would guide her through her pregnancy and deliver her baby in a hospital, like 98 percent of other childbirths in America.

But Las Vegas has a well-documented doctor shortage, and Yeager got multiple rejections from obstetricians shunning new clients. When she finally found one, she left her initial appointment disillusioned. She had felt rushed, ignored, like a number. She vowed never to return.

“He didn’t take time to listen to my concerns,” Yeager said. “I felt like I was just pushed out of there. He didn’t even want to meet Michael.”

Michael Brooks, now Yeager’s husband, was the baby’s father. They were excited to welcome a child into their family.

But they needed to find a new obstetrician.

One of Yeager’s friends recommended a local midwife, an older woman whom Yeager visited once but didn’t like. This midwife did group appointments. Yeager sought something more private.

Then she found Collins, who had moved to Las Vegas a few months earlier and was practicing under the name Home Sweet Birth despite her ongoing probation in California.

The court’s terms didn’t forbid Collins from crossing state lines, but it did require she not practice midwifery without a license. Since Nevada doesn’t require a license for midwifery, Collins violated no terms.

Unlike California, Nevada has no oversight or regulation of the trade. Anyone can practice regardless of education or training. They can accept any clients — even high-risk cases — and make any decisions about care.

Their first visit lasted three hours. It took place in Collins’ sprawling, two-story rental house in the North Las Vegas suburb of Lone Mountain, where she converted one of her family’s five bedrooms into a clinic. It overlooked the property’s tiled pool, hot tub and outdoor fireplace.

Collins made Yeager and Brooks feel comfortable. She answered their questions and allayed their concerns. She was warm, personable and professional.

Gavin Michael Brooks was due Feb. 4, 2014. Yeager calculated the date based on her last menstruation.

A full-term pregnancy ranges from 39 to 41 weeks, according to the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. After that, fetal mortality rates increase for any of several reasons — umbilical cord compression, placenta degradation or meconium aspiration, which is when the baby inhales its own stool in utero.

Collins told Yeager not to worry about the due date.

“She said the stuff you hear so often,” Yeager recalled. “'Mother’s body knows exactly how to birth their babies, and babies know exactly how long they’re supposed to be in and when they’re supposed to be born.’”

A quote on Collins’ website at the time reaffirmed this philosophy: “Just as a woman’s heart knows how and when to pump, her lungs to inhale, and her hand to pull back from fire, she knows when and how to give birth.”

The expectant parents hired Collins on the spot and paid half of her $5,000 fee upfront and the other half a month later. It covered prenatal and postpartum care, labor and delivery, a newborn examination and breastfeeding assistance.

“Everything seemed so perfect,” Yeager recalled. “We were going to have this perfect, natural, beautiful home birth with her.”

Both Collins and Yeager acknowledge several problems plagued the last weeks of the pregnancy. But their stories diverge from there.

Collins said she repeatedly urged Yeager to seek medical attention during this time but that her client refused. Yeager said Collins never told her to go to the hospital and, in fact, recommended against it.

Text messages, prenatal records, and interviews with other sources confirm the mother’s account.

As Gavin’s due date approached and then passed, Yeager started to feel like something was wrong. Whereas her baby seemed ready to drop into a birthing position a few weeks ago, he now felt lodged inside her, like he wanted to stay forever.

Yeager wondered if a car accident she had at 36 weeks compromised the baby. Collins told GateHouse Media she advised Yeager to seek medical attention for her baby after the wreck, but her text messages from the time say differently: “Babies are so well protected in there.” “Definitely need to see a chiro now.” “You deserve a long soak in the tub.”

Prenatal records provided by Yeager show no entry on the date of the accident. Collins said Yeager’s records are incomplete but declined to provide GateHouse Media a copy of her own files.

Or maybe it was an incident that happened three days after Gavin’s due date, when a coworker jokingly pushed on Yeager’s belly to get the baby moving. Yeager felt nauseated afterward. Collins told GateHouse Media she advised Yeager to seek medical attention for her baby after the incident, but her text messages from the time say differently: “I’m sure the nausea is from being so upset.”

Prenatal records show no entry on the date of the incident.

Or maybe it was stress from her 41-week checkup, when her mother and Collins argued about whether Yeager needed a hospital induction. Collins said she advised her client to seek medical attention over the objections of Pam Yeager.

But mother and daughter said it was Collins who objected to hospitalization and Pam Yeager who insisted the baby needed a doctor.

“I told her, ‘Go to the hospital, don’t deal with her,’” Pam Yeager said. “But that idiot had her stay home.”

Prenatal records show no mention of the dispute or the hospital recommendation on the date of the appointment. Collins said she did not ask Yeager to sign an informed refusal statement.

When she hit 42 weeks, Yeager believes her water broke. She told Collins, but the midwife said it was probably a false alarm. Collins said she doesn’t recall that conversation.

Most states that regulate out-of-hospital midwifery require practitioners to involve a physician when clients go past 42 weeks. In Nevada, Collins could do what she wanted.

She advised her client to get a biophysical profile, or BPP. The test uses an ultrasound and a heart-rate monitor to measure the baby’s physical activity, heart rate, breathing movements, muscle tone and amniotic fluid level.

George Drenes, a sonographer from SonoCare, performed the procedure on Feb. 19, 2014, and noticed a complete lack of amniotic fluid. The fluid is supposed to protect the baby, regulate its temperature, fight infection and cushion the umbilical cord.

Its absence means the baby is exposed and possibly in distress.

Drenes can’t share test results with patients — only their medical providers — so he let Yeager leave and phoned her midwife.

“That’s a big deal,” Drenes said of the lack of aminiotic fluid. “I would have said, ‘We have a big problem.’ Our doctor sends patients to the hospital when their water gets to 5 centimeters. I’m surprised Christy didn’t send her client to the hospital right away.”

Collins wanted to send Yeager home instead.

“Baby looked really fantastic, however George visualized zero amniotic fluid around the baby,” Collins texted Yeager. “We need to talk about natural induction unfortunately which would include stripping/sweeping membranes today as well as nipple stimulation at home afterwards and sending you home with herbs to start things up.”

The two then spoke on the phone. Collins said that’s when she told Yeager to go to the hospital. Yeager said that’s when Collins told her to drink more water and get a second BPP.

Yeager drank several liters of water and went for a second BPP that afternoon. The results were the same.

Rehydration can replenish some amniotic fluid. But at this advanced stage of the pregnancy, its total lack signals placenta dysfunction, said Rita Ledbetter, an advanced nurse practitioner and certified nurse midwife at Genesis Health Group in Iowa, who reviewed Yeager’s medical records as part of a lawsuit.

The fact Collins ignored the seriousness of the condition, Ledbetter said, was grossly negligent.

“It is a very dangerous situation, and it is an emergency situation when the baby is past its due date,” said Lise Hauser, an advanced nurse practitioner and certified nurse midwife at Advocate Illinois Masonic Medical Center who also reviewed Yeager’s medical records as part of a lawsuit.

“The only correct response,” Hauser said, “is to send that mother to the hospital.”

Yeager went to Collins’ home office after the second BPP. The midwife stripped her membranes to induce labor. Then she sent Yeager home with an herbal concoction to drink every few hours and a hand-held Doppler fetal monitor to check Gavin’s heartbeat.

It was a rough night. Yeager and her boyfriend fumbled with the monitor. Contractions came sporadically but never consistently. They got no sleep.

Collins said she didn’t hear from Yeager at all that night. But text messages show more than 100 exchanges between 8 p.m. and 11 a.m. the next day. They show Collins instructing Yeager to drink castor oil to hasten contractions; Yeager refused. At another point, Collins suggested a massage and acupuncture.

That same night Collins contacted another midwife, Tiffanie Gonzales. Collins said she sought advice on how to get her stubborn client to the hospital. Gonzales said Collins sought advice on treating Yeager’s condition herself.

“I recommended they go in” to the hospital, Gonzales said. “But she didn’t seem that concerned about it. She told her (client) to take a bath.”

The next morning, Collins scheduled another BPP for Yeager.

Then she sought advice from another source: Jan Tritten, the founder and editor-in-chief of Midwifery Today magazine. Tritten posted Collins’ case on her Facebook page : Baby at 42 weeks and 2 days gestation; no amniotic fluid but a good placenta, normal kidneys and normal amount of urine in its bladder.

Tritten asked her followers, “What would you do?”

The post generated dozens of comments from midwives, many of whom recommended waiting it out.

But as these midwives chimed in, Gavin was already dying inside his mother’s womb.

It was a cool, sunny Thursday afternoon in February 2014.

Collins stood in the plain-looking doctor’s office. Now 36 years old and pregnant with her own child — her sixth — the midwife watched a screen as a different sonographer moved a wand around Yeager’s belly. Still no amniotic fluid.

Alone, midwife and clients discussed the results and their options. Collins pulled out her phone and read them comments from the Facebook post. She said she read them the ones urging hospital induction; Yeager and Brooks said she only read them the ones advising them to wait.

They decided to check Gavin’s heart rate again. Collins took the Doppler wand and placed it on Yeager’s belly, moving it around until they could hear the whoosh-whoosh-whoosh of the heart.

It sounded different this time. Slow. Dangerously slow. A number appeared on the monitor: 90 beats per minute. Not the normal, healthy fetal heart rate of 120-160 bpm.

“At that point, I said, ‘We need to go,’” Brooks recalled.

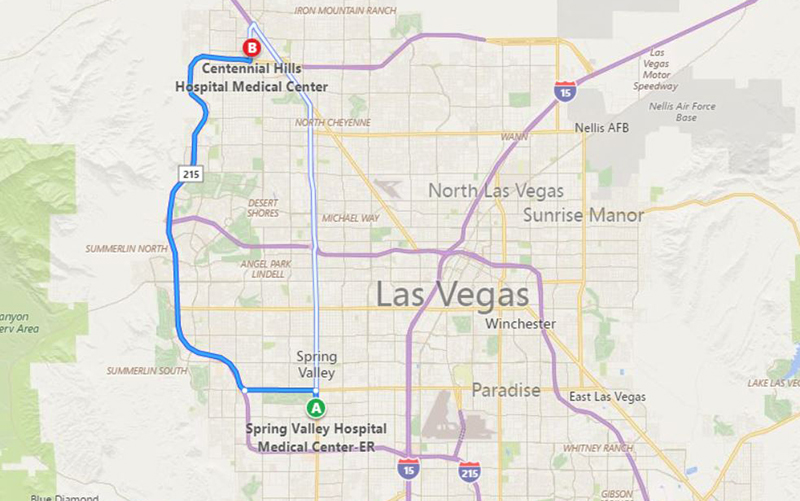

Although they were in a clinic connected to Spring Valley Hospital near the heart of Las Vegas, Collins instructed them to meet her at Centennial Hills Hospital, more than 16 miles north. It’s about a half-hour trek.

Collins said Yeager refused to stay at Spring Valley and insisted upon Centennial. Yeager said it was Collins who made that call.

Brooks drove as Yeager sprawled on the backseat sobbing and moaning, “Our baby’s not going to make it. Our baby’s not going to make it.”

“Yes, he is,” Brooks told her.

“No, he’s not,” Yeager said. “I can feel it.”

Collins raced ahead of the couple in her own vehicle. She dialed the hospital to alert them of their pending arrival and requested that Steven Harter receive them.

A beloved obstetrician in Las Vegas’ natural birth community, Harter has allowed midwives to continue providing client care at the hospital whereas other physicians relegate them to the waiting room. As such, many midwives specifically ask for him during a transfer, he said.

Collins referred to Harter as her “backup physician.” She touted this relationship to Yeager and Brooks during their initial consultation. It’s one of the reasons they liked her: She had a backup doctor. How reassuring.

But Harter told GateHouse Media he had never seen Collins before she rushed into the hospital that day. He was not her backup physician and never had been.

Harter was waiting when Yeager arrived, and after a quick check of the baby, determined she needed an immediate C-section. Staff stripped off her clothes and wheeled her into an operating room.

Yeager went into shock, her body flopping wildly on the table. Nurses pinned her limbs as the anesthesiologist gave her an epidural and Harter sliced into her abdomen.

Gavin emerged from the incision below his mother’s belly button at 3:20 p.m., covered in blood and meconium . A dark, sticky substance, meconium is the baby’s first stool. Gavin had emptied his bowel in the womb, a common sign of distress, and sucked it into his lungs where it blocked his airway.

Although babies don’t breathe in utero, they make breathing movements as early as the first trimester and by the end of the last trimester occasionally inhale and exhale amniotic fluid — or whatever else is with them in the womb.

Neonatal intensive care staff tried to suction the meconium from Gavin’s mouth, his trachea and his lungs. They prodded and pumped and sucked at his body for 47 minutes but could not save him. He was dead.

Gavin might have survived, Harter said, had Collins sent her client to the hospital earlier.

The next two days brought the kind of torment only empty-armed parents know. Other babies’ cries and other families’ coos wafted into Yeager’s room at Centennial, where she recovered from her C-section with Brooks at her side. Each vocalization anguished them.

Collins shared in their grief, crying with them at the hospital and saying there was nothing else they could have done, that some babies just die.

But as the couple mourned, Collins took to Facebook, claiming she tried to warn Yeager that her baby could die. In a private message shared with other midwives, Collins said she wishes she would have used stronger words to convince Yeager to go to the hospital. The private message was shared, and eventually became public.

Collins never mentioned the hospital, said Yeager’s brother, Adam, who attended nearly every appointment with his sister, including those at the end of the pregnancy.

“I didn’t even know the word ‘hospital’ was in her vocabulary,” Adam Yeager said.

Yeager and Brooks didn’t know Collins was blaming them online. Nor did they yet know she had solicited help from Tritten prior to Gavin’s death.

“We thought at first that she just didn’t know any better,” Yeager said. “But a few weeks later, my parents came over and showed us stuff from the internet where people were talking about my case, and they said, ‘Before your baby died, she put your situation online, asking people what to do.’”

It took several months before the couple fully grasped what had happened. They pieced it together from Yeager’s medical records and her mother’s sleuthing.

It was Pam Yeager who discovered Collins’ legal trouble in California; Collins was still on probation at the time of Gavin’s death. Her crime never appeared on the state’s online registry of midwives, because Collins never was a midwife in California — at least not legally.

Pam Yeager and her husband, Lee, also found the Facebook post soliciting midwives’ input on their daughter’s case. And they found Collins’ claims blaming their daughter for the baby’s death.

Yeager’s medical records offered other clues, like inaccuracies about the day of Gavin’s death. The records say Yeager initially declined hospitalization and further refused admission to the closer Spring Valley Hospital so that she could go to Centennial instead. The records since have been updated with accurate information, Harter confirmed.

“She lied,” Pam Yeager said of Collins. “She tried to cover up what she did by blaming us.”

Gavin’s death nearly ruined their lives — Yeager sank into a deep depression; Brooks drank himself into oblivion; both stopped working and cut off contact with friends — but Collins continued practicing midwifery.

It didn’t seem fair. Yeager wanted Collins held accountable for her actions.

“I called the medical board, I called the nursing board, I called everywhere, and there was nothing I could do,” Yeager said. “Nevada has basically no laws over midwives. I even called NARM, and NARM was ridiculous.”

The North American Registry of Midwives told Yeager that Collins let her credentials expire; it could therefore take no action. NARM declined to discuss Collins other than to confirm she first became a member in 2010 and was active as of August.

But a group of local midwives held a peer-review meeting after the incident and called Collins to testify. Its members found Collins had acted improperly, but because the group had no official authority to discipline Collins, it could take no action against her.

“I don’t recall her saying anything that the client wouldn’t go to the hospital,” said Sherry Hopkins, one of the midwives at the meeting. “There was a lot of self-righteousness, like she felt she was very qualified and capable and we couldn’t tell her anything she didn’t already know.”

Since no one else would hold her accountable, the couple hired an attorney and filed a civil malpractice claim , exactly one year after their son’s death. Three medical professionals, including Ledbetter and Hauser, provided affidavits in the case directly blaming Collins for the outcome.

The “care and treatment of Danielle Yeager and her unborn child Gavin fell so far below any standard of care, as to amount to a willful and conscious disregard for the safety of both Danielle Yeager and her unborn child with the result of causing (his) death,” wrote Charles Dubin, a board-certified obstetrician and gynecologist with more than 30 years of practice in California.

Yeager and Brooks wanted Collins to reimburse them the money they paid for her services, plus the roughly $16,500 hospital bill they incurred from the C-section, as well as attorneys’ fees and court costs.

“We didn’t want money,” Brooks said. “My son is dead. You can’t pay me enough. But we wanted her to admit her guilt.”

Instead, Collins and her husband declared bankruptcy.

In their March 2015 filing , the midwife listed her profession as a direct-sales presenter of cosmetics earning no monthly income. Her husband, Charles Collins, listed a gross monthly income of $10,130 as an Air Force air traffic controller.

The court approved the bankruptcy three months later, absolving the couple of all financial responsibilities, including anything related to the lawsuit.

“My lawyer warned us about this,” Yeager said. “If she files for bankruptcy, she doesn’t have to go to court or pay us a dime. So my case was closed.”

Collins said she wanted to fight the lawsuit but felt overwhelmed by other aspects of her life, including a new baby and a recent diagnosis of autism in one of her sons.

“It was such a horrible situation,” Collins said. “I could not deal with it mentally. It changed me as a person.”

Collins and her family moved shortly thereafter to the coastal Florida community of Navarre, where they bought a newly constructed, four-bedroom, three-bathroom house for $373,300, county records show .

Florida is one of 32 states that regulate midwifery, and like California, it requires its practitioners to obtain a state license.

Collins wasn’t among the state’s licensed midwives as of mid-November. But she remains connected to the natural childbirth community and offers her services in placenta encapsulation. In a Facebook post from June, Collins offered to dehydrate and grind placentas into powder to fill dozens of gelatin capsules for consumption. Her price: $200. It’s purported to alleviate postpartum depression.

Although Collins wants to practice midwifery again, she fears Yeager’s story will forever haunt her.

“None of it is true,” Collins said. “It has been difficult for me to keep this inside for so long knowing she is absolutely, outright lying. She ruined my career and I can’t forgive her for that.”

Yeager bristled.

“I ruined her career?” Yeager said. “She ruined my life.”

It was a cool, sunny Tuesday morning in April 2017.

William Brooks arrived into the world, exactly three years and three months after his brother’s original due date. He was born in a hospital, via a planned C-section with an obstetrician.

A curious child with brownish-gray eyes and soft blond hair, William resembles his mother, whereas Gavin looked like his father.

His lively presence eases the pain of his parents’ earlier loss. But it does not erase it.

“For me, having the perfect, natural, beautiful home birth is not worth losing your child,” Brooks said one Monday afternoon in August.

He held William on his lap, his wife sitting beside them. The toddler wiggled and smiled.

“I would take a C-section birth and a week or two of discomfort for a lifetime of happiness with a child,” Brooks said, “as opposed to having this perfect, magical moment in a tub with some lady that you’ve known for nine months telling you to push, and then you lose your child.”

William grabbed for a wooden box his parents cradled between them. It looked small enough to play with and had a white angel figurine atop.

Inside were his brother’s ashes. Outside, a metal plaque:

Gavin Michael Brooks

February 20, 2014

The Cutest Baby Ever