‘Midwife’ sues Georgia Board of Nursing

State bans top U.S. midwifery group official from calling herself a midwife.

By Lucille Sherman

December 20, 2019

A top official for the North American Registry of Midwives is suing the Georgia Board of Nursing over its ban on her use of the title “midwife” because she is not licensed in the state.

Debbie Pulley, who serves on the credentialing body for the largest group of non-nurse midwives in the country, said the board’s actions violate her First Amendment rights. She filed the claim on Dec. 11 in the U.S. District Court in Atlanta, specifically naming board President Janice Izlar as the defendant.

Neither the board nor Izlar has filed a response through the court, records show.

The Georgia Board of Nursing investigated Pulley after GateHouse Media — now part of the USA TODAY Network — found her practicing unlawfully as part of its “Failure to Deliver” investigation into the rise and risks of out-of-hospital births.

Georgia restricts midwifery to only people with a current certification from the Georgia Board of Nursing to practice as a certified nurse-midwife.

Pulley is not a certified nurse midwife. She is a certified professional midwife, a credential provided by the North American Registry of Midwives — or NARM — to those who complete a midwifery program or apprenticeship and pass a capability test. Certified professional midwives are not required to have nursing degrees, and some have no more than a high school diploma.

As a result of its investigation, the board issued Pulley a cease-and-desist order in June, demanding she stop calling herself a midwife and threatening to fine her $500 for each violation, according to the lawsuit and a copy of the final order.

Pulley responded by removing all references to her certified professional midwife credential — and the term midwife in general — from the NARM website, her social media account and the website of the Atlanta Birth Care, where she now works as an office manager, her federal complaint states.

Pulley had been assisting with births in Atlanta for 38 years, according to her website. But she claimed in the lawsuit that she no longer practices and instead advocates for midwifery through her role with NARM.

The board finalized the order Dec. 2. Pulley filed her lawsuit the following week.

“The state of Georgia can’t ban words,” said Pulley’s attorney Jim Manley. “I am an attorney. I’m licensed in Arizona and Colorado, but if I go to Georgia, I am still an attorney. It’s accurate for me to describe myself as an attorney if I’m giving legislative testimony or talking to someone about this case, even though I can’t hang a shingle and write wills for people.”

The same should apply to Pulley and her title as a midwife, Manley argued.

“Debbie is a certified professional midwife, and the First Amendment protects her right to say that,” Manley said. “It’s important for her to be able to talk about her qualifications and experience when she is advocating for midwifery.”

The Georgia Secretary of State’s communications director, Ari Schaffer, who also represents the Board of Nursing, would not speak about the order or Pulley’s lawsuit. Shaffer referred the USA TODAY Network to the attorney general’s office, which also declined to comment.

More than 30 states currently license non-nurse midwives like Pulley. Around a dozen states lack laws or regulations governing the practice. Georgia, along with North Carolina, the District of Columbia and Illinois, ban non-nurse midwives from practicing at all.

Dozens of the North American Registry of Midwives’ members are located in those states that ban non-nurse midwives, according to the organization’s most recent annual report.

The organization shields those midwives by denying the public access to its roster. In an interview last year with USA TODAY, Pulley said releasing that information could jeopardize those who violate state laws or regulations.

“We don’t know necessarily where they’re practicing,” Pulley said at the time. “We don’t care to find out.”

Non-nurse midwives have unsuccessfully lobbied state lawmakers for years to license and regulate them.

Until Georgia “creates a legal path of licensure for the Certified Professional Midwife,” Pulley’s website states, “I will not be practicing clinically.”

Georgia investigating unlicensed midwife

After a mother's viral blog post about her baby's death, the state is taking action.

By Lucille Sherman

September 27, 2019

Ashlyn and Gabriel Cruz picked a name for their daughter a few months before she was born.

They would call her Asa, Hebrew for “healer.” It’s a name from the first Book of Kings in the Old Testament. Her middle name would be Joy.

But after some 60 hours of labor at home in May, when Ashlyn Cruz finally got to hold Asa Joy in her arms, it was too late. Her daughter had died in utero at least 10 hours earlier.

Had the Dearing, Georgia, mother planned to deliver her baby in a hospital, Asa would have lived, Ashlyn Cruz told GateHouse Media. Instead, the family trusted an unlicensed midwife to guide them through the process.

“This shouldn’t have happened,” the 28-year-old mother said on the phone, as her almost 3-year-old son called for her in the background. “She was perfect. Asa was healthy.”

The Georgia Board of Nursing opened an investigation Thursday into the midwife, Cindy Morrow, and her unlicensed practice. The case since has been referred to investigators in the Secretary of State’s Office, according to its press secretary, Tess Hammock.

The family also retained an attorney and is pursuing a lawsuit.

Morrow declined to comment on Cruz’s case, saying in an email to GateHouse Media that privacy laws prevent her from doing so. But she said she disputes the family’s narrative.

“I was devastated and traumatized by the outcome of this birth, and I have complete empathy and compassion toward baby Asa's grieving parents in their loss,” Morrow wrote. “However, I believe that I provided the best care and support that I was able to provide to this family, in the context of their choices and the marginalized, vulnerable status of home birth midwives in the state of Georgia.”

Only nurse midwives can legally practice in Georgia, according to state rules. But many non-nurse midwives practice openly in the state, seemingly without consequence.

Morrow is one of them. Although she is certified as a professional midwife — or CPM — by the North American Registry of Midwives, Morrow is not licensed by the state of Georgia and is not authorized to practice there.

Non-nurse midwives have lobbied state lawmakers for years to license and regulate them. Some recently pointed to Asa’s death as evidence the state needs to act.

“We are confident that licensure similar to the other 33 states that license CPMs will help GA families in identifying adequately trained and licensed providers for community birth. It will also provide an avenue of recourse by families,” the Georgia State Chapter of the National Association of Certified Professional Midwives posted Tuesday on Facebook.

When Cruz hired Morrow for her May delivery, she said she didn’t know the midwife lacked a state license or the legal authority to oversee her birth.

Morrow told GateHouse Media that all of her clients sign an informed consent document acknowledging her status as an unlicensed midwife in Georgia. But the document Cruz received, which she shared with GateHouse Media, had no such disclosure.

Cruz, who owns a business selling children’s shoes made by Nicaraguan artisans, had delivered Asa’s older brother, Michayah, via C-section. She wanted to have what she considered a more natural birth with Asa.

After serving as missionaries in Nicaragua for a year, the Cruz family moved back to the United States, settling in Georgia in October 2018.

When Cruz found out she was pregnant, she sought a provider who would let her have a vaginal birth after cesarean section — or VBAC, which carries a roughly 1 percent risk of uterine rupture, and can be fatal to both mother and baby if not treated immediately.

That’s when she found Morrow, who was willing to oversee the high-risk delivery.

“I viewed it as she was willing to take on a mother who wanted what was best for her body and her baby,” Cruz said.

In addition to receiving prenatal care from Morrow, Cruz said she also twice visited Atlanta-based OB-GYN Brad Bootstaylor on the recommendation of her midwife. Known for championing natural birth, Bootstaylor performed two sonograms, Cruz said.

He also assured Cruz she was a good candidate for home birth and in good hands with Morrow, she said.

“He was promoting the fact that she would be qualified to do a job,” Cruz said. “That’s why I felt so secure in Cindy. How would an obstetrician be backing up an illegal midwife, and saying that what this lady is doing is okay?”

GateHouse Media made multiple attempts to reach Bootstaylor, including leaving a message at his practice, but he did not respond.

Cruz said Bootstaylor also agreed to serve as her backup doctor in case she needed a C-section and that he prescribed her Ambien upon the midwife’s request.

Morrow, who is not a licensed medical professional, told the mother she could donate the prescription drugs if she did not use them.

“I will request a prescription for Ambien be called in for you in preparation for labor … ,” Morrow wrote Cruz in a March 25th email that was shared with GateHouse Media. “If you end up not using it, I am happy to have donations to have on hand for those Moms who do not have a back up doctor/rx.”

Cruz was 39 weeks and 3 days along when contractions began. In the nearly three days that she labored at home, the mother was without midwifery care for hours after Morrow left the residence three times — twice to go to a hotel and once to get breakfast, she said.

“She lied to me,” Cruz said. “She said she would be at the home and be there the entire time.”

Cruz estimates that Morrow checked her four or fives times while she was in labor. Each time, she said, Morrow assured the mom all was well.

But it wasn’t until a day and a half after Cruz’s water broke with meconium — the baby’s first stool and a possible sign of distress — that Morrow told the family it might be time to go to the hospital, Cruz said.

Morrow’s labor notes, a copy of which the family provided GateHouse Media, showed the baby’s heart rate, though hard to locate, was between 120 and 128 an hour before hospital transfer.

But when they arrived, hospital staff could not find Asa’s heartbeat.

They detected only the mother’s heart rate, Cruz said. The heart rate Morrow had found was hers, not her baby’s, Cruz explained through tears.

Doctors rushed Cruz into surgery and performed an emergency C-section to get Asa out.

Asa had died an estimated 10-24 hours before doctors delivered her via emergency cesarean section, the family said. It was so long that she had begun to deteriorate in utero — her skin peeled off at the touch.

When Cruz awoke, she cried for Asa, and asked where she was.

Her husband broke the news to her, and the couple held their daughter close. She had a full head of hair that was curly just like her dad’s, and a nose just like her mom’s.

“I’m just so angry,” Cruz said.

Cruz wrote about her tragic experience on her blog, the Humble Soles, and blamed Morrow for her loss. The Sept. 17 post had received nearly 1 million views more than a week after it was posted. At least one additional mother has come forward since then, saying she had a similar experience with Morrow.

Whitney Welch, a Georgia mother of four who attempted to deliver her youngest in a home VBAC earlier this year, said she also was neglected by Morrow. Welch’s son was delivered in April by emergency C-section 10 days after her water broke. The doctor told Welch that if she had waited any longer, her baby wouldn’t have survived, the mother wrote in a blog post.

“I wish I would’ve spoken up before,” Welch told GateHouse Media. “Had I spoken up, maybe Ashlyn would’ve known better.”

Cruz said she hopes Georgia will adopt regulations for non-nurse midwives like Morrow so it can regulate them and hold them accountable.

“There has to be better outlets for moms to know who is what and who can do what,” Cruz said. “I did my research, and everything looked perfect to me.”

Oklahoma midwife charged with felony

'The details of this case are disturbing,' attorney general said.

By Lucille Sherman

September 13, 2019

The midwife involved in a botched delivery that drew media attention after the mother’s emotional Facebook post went viral was charged with a felony Friday in Oklahoma, a state that does not license or regulate non-nurse midwives.

Oklahoma Attorney General Mike Hunter charged certified professional midwife Debra Disch with practicing medicine without a license and issued a warrant for her arrest.

“The details of this case are disturbing,” Hunter said in a press release. “Our evidence shows that Disch was reckless in the way she performed this procedure and she was entirely outside the scope of her abilities and the law. The mother and her baby are lucky to be alive.”

The move comes less than a month after Disch’s former client, Suzie Bigler, shared the story of her traumatic out-of-hospital birth on Facebook. The Aug. 17 post garnered 1,900 likes, 660 comments and 2,100 shares in less than a week.

The post also drew local media attention from a television station and The Oklahoman, which published a story about it in collaboration with GateHouse Media’s national reporting team.

The Attorney General’s Office opened its investigation shortly after the story published, its spokesman said.

“It amazes me that our story has gotten this big,” Bigler said. “I hope that the impact is lasting. Ultimately if we could get regulations for midwives in the state of Oklahoma, that would save even more moms.”

Bigler had labored for nearly three days before Disch delivered her baby May 27 at an unlicensed birthing home in Roland, Oklahoma. The boy emerged lifeless and required resuscitation. After Disch performed an episiotomy, Bigler hemorrhaged so much that her blood count was nearly half the normal amount when she arrived at the hospital, the mother said.

Both Bigler and her son, Spencer, stayed in the hospital for several days. Bigler underwent surgery to remove blood clots and repair her episiotomy. And the baby was found to have a hematoma — localized bleeding — due to the injury, the mother said.

“I don't know that I could live with myself if the outcome would have been different,” Bigler said in an interview last month.

The Attorney General’s Office specifically cited two things it said Disch did that violate state law: Performed an episiotomy and administered Pitocin, a drug that helps control bleeding.

“Although individuals in Oklahoma do not need a license to practice as a midwife and despite Oklahoma having no laws regulating midwives, individuals must have a medical license to perform an episiotomy and administer Pitocin,” Hunter said.

The offense is punishable by up to four years in prison and a $10,000 fine.

Disch admitted to investigators that she performed the episiotomy and administered the drug, according to the affidavit. Investigators also found five vials of Pitocin along with other medical and surgical equipment during a search of her birthing center on Sept. 4, the affidavit states.

Disch, who also is barred from practicing midwifery in Arkansas, did not immediately respond to a request for comment.

“We hope these charges send the message to Oklahomans looking to hire a midwife to research and choose carefully,” Hunter said in a press release.

The Attorney General’s Office could not speak to what the charges against Disch mean for other non-nurse midwives practicing in the state.

“Our decision was limited to the facts, evidence and interviews in this case,” communications director Alex Gerszewski said. “Based on our investigation, we thought this individual represented a threat to the health and safety of Oklahomans.”

About a dozen states, including Oklahoma, neither license nor regulate non-nurse midwives. Anyone can hang a shingle and deliver babies outside the hospital.

Because of its lax laws, at least two midwives facing discipline in other states have opened practice in Oklahoma.

Disch is among them. The Arkansas Board of Health in 2016 fined and eff ectively barred Disch from obtaining a midwifery license, saying she demonstrated “a lack of regard for the clinical safety and disregard for Arkansas law governing the practice of midwifery.”

She also has an open warrant for practicing midwifery without a license.

Shortly after her discipline, Disch crossed state lines and continued her practice in Oklahoma.

“I applaud the Attorney General’s Office,” said anesthesiologist and former state Sen. Ervin Yen, who introduced bills to regulate non-nurse midwives in the state two years in a row. His efforts failed.

“This absolutely needs to be done,” Yen said. “The number of home births in Oklahoma has soared, and we need to protect these mothers and fetuses.”

Troubled Arkansas midwife practicing in Oklahoma

A mother’s viral Facebook post about her traumatic birth highlights state’s lax laws.

By Lucille Sherman

August 23, 2019

A midwife with an open warrant for practicing without a license in Arkansas is delivering babies in Oklahoma, a state with no oversight of non-nurse midwives.

Certified professional midwife Debra Disch’s troubled past came to light on Aug. 17 after an Oklahoma mother who had hired Disch shared her traumatic out-of-hospital birth experience on Facebook.

Suzie Bigler’s post went viral, garnering more than 1,900 likes, 660 comments and 2,100 shares in less than a week. Her story also was picked up by at least one TV station.

Bigler said she didn’t know about her midwife’s outstanding warrant or previous problems until after her delivery.

“I can't believe I didn’t look,” said Bigler, 27, of Spiro, Oklahoma. “I was very trusting.”

Do you have a similar experience with a midwife?

Bigler had labored for nearly three days before Disch delivered her baby at an unlicensed birthing home in Roland, Oklahoma, on May 27, the mother said. The boy emerged lifeless and required resuscitation. Bigler also hemorrhaged so much her blood count was nearly half the normal amount, she said.

Both mother and baby were rushed to a hospital. They are now doing well, though the baby spent time in the NICU and the mother underwent surgery as a result of the birth trauma, Bigler said.

Disch had been delivering babies unlawfully in Arkansas for years when the State Board of Health became aware of her in 2014, state documents show. Although Disch is certified by the North American Registry of Midwives, she never got licensed by the state, which is required for practice.

Two years later, in January 2016, the District Court of Scott County issued Disch a warrant for practicing midwifery without a license. Around the same time, the State Board of Health fined and effectively barred Disch from obtaining a midwifery license, saying she demonstrated “a lack of regard for the clinical safety and disregard for Arkansas law governing the practice of midwifery.”

The board also determined Disch had delivered twins and helped women birth vaginally at home after previous Cesarean sections. The state bans both practices even for licensed midwives.

Disch isn’t the first midwife to relocate to Oklahoma and continue practicing after facing discipline elsewhere.

Non-nurse midwife Venessa Giron moved her practice to Oklahoma after her license was revoked in Arkansas in January 2016, a recent GateHouse Media investigation found. And Dawn Karlin, who lost her Oklahoma nurse midwife license last year after two fatal attempted home births, continues to practice in the state as a non-nurse midwife.

Oklahoma does not license or regulate non-nurse midwives, so anyone can call themselves a midwife and practice as one. And they can do so with few repercussions for substandard care. There is no state agency for families to turn to when things go wrong, and there are few ways for mothers to vet their midwives.

“That just shows it’s too easy in Oklahoma, if anybody can do it,” said Oklahoma state Rep. Lundy Kiger, R-Poteau, who represents Bigler’s district. “It puts the child at risk.”

Tattoo artists are regulated, he said. “Childbirth can be a little more dangerous than getting a tattoo.”

Disch lives in Fort Smith, Arkansas, but she told GateHouse Media she no longer practices in the state and serves clients only in Oklahoma. Disch’s website, by contrast, says she serves the “Fort Smith River Valley of Arkansas” in addition to eastern Oklahoma.

Text messages obtained by GateHouse Media also show Disch telling Bigler she could birth at Disch’s Fort Smith cottage — evidence the midwife might still be practicing unlawfully in her home state.

The Arkansas Department of Health declined to comment.

Law enforcement will travel only 50 miles within the state for misdemeanor warrants, the county sheriff’s office said. Fort Smith is 55 miles from Scott County.

GateHouse Media obtained a copy of the warrant, but Disch disputed its existence, saying she had a “very reputable source in the judicial system” who checked into it for her.

“I was a midwife long before the licensing thing came out,” said Disch. “At that time and still now, the Arkansas protocols take away the parents’ choices.”

Arkansas began licensing non-nurse midwives in 1987.

Disch said she never hid from clients the fact that she was unlicensed in Arkansas.

“They had to know,” Disch said of her clients. “That was the only way I could do that.”

In an affidavit submitted for the warrant, one of her former clients said she believed Disch was a licensed midwife when she hired her in 1999 and again for four subsequent births. In 2015, the mother said she planned on using Disch for another birth but discovered through her local health department that she was unlicensed.

“If people ask about my past, I’m happy to talk about,” Disch said. “I’m not trying to hide that part of my life.”

But because Bigler didn’t ask, she said she didn’t know about Disch’s past. The first-time mother said she would not have hired her otherwise.

“Everything was perfect, until it wasn’t,” Bigler said. “It’s just that when things got bad, they got bad really quickly.”

Bigler was more than a week overdue when she started having contractions. After laboring at home for 32 hours, Bigler said, she went to the birthing home and labored an additional 37 hours. Several times, she said, Disch attempted to hasten delivery by pressing on Bigler’s abdomen.

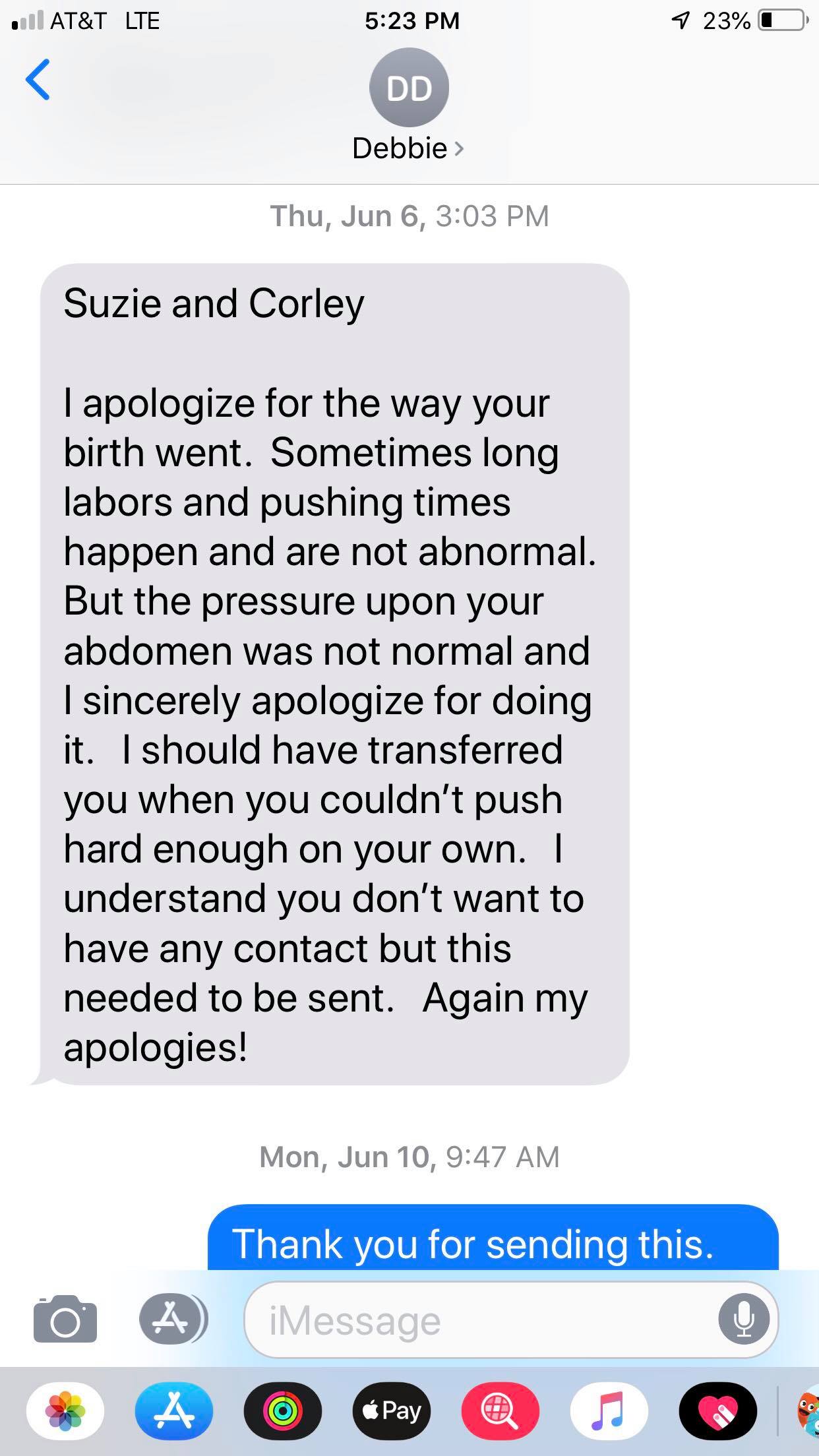

Disch later apologized to Bigler for pushing on her belly, according to a text message obtained by GateHouse Media. The midwife also admitted she should have transferred Bigler to the hospital earlier.

“I should have transferred you when you couldn’t push hard enough on your own,” Disch wrote in one text message.

Instead of transferring, Disch let Bigler continue to labor. Disch then realized the baby was malpositioned and, according to the mother, decided to perform an episiotomy to get the baby out, even though she said she had never done it before.

When Baby Spencer was born, he emerged lifeless.

“I remember thinking over and over, ‘He should be crying,’” Bigler said, through tears. So she started talking to him. “I was just pleading and pleading with him to talk to me.”

While attempting to resuscitate Spencer, the midwife dropped him, Bigler said. The boy eventually began breathing.

Around the same time, Bigler said, she began hemorrhaging. Only then were Bigler and her baby transferred to the hospital. By the time Bigler arrived, her blood count was nearly half the normal amount, the mother said.

Bigler underwent surgery to remove blood clots and repair her episiotomy. And Spencer was found to have a hematoma — localized bleeding — due to the injury.

Bigler and Spencer both were stabilized and left the hospital several days later without any major issues, though Spencer’s hematoma is still visible and Bigler is still taking iron to supplement her blood supply, she said.

“I don't know that I could live with myself if the outcome would have been different,” Bigler said.

Disch did not comment on the specifics of the birth, citing the federal law restricting release of medical information, HIPAA.

“I’m sorry she’s unhappy,” Disch said. “There are two sides to every story, and my hands are pretty tied.”

Since Bigler shared her story publicly, she said, several mothers and local medical providers have reached out to her privately, sharing their own troubling experiences with Disch.

“I felt an obligation to the women in our community to get it out there,” Bigler said. “It was so horrific, I would never want anyone else to experience that.”

‘Failure to Deliver’ midwife disciplined

By Emily Le Coz

August 17, 2019

One of the midwives profiled by GateHouse Media and the Sarasota Herald-Tribune in their “Failure to Deliver” investigation was sanctioned in New York for numerous violations committed during her care of three clients, including the attempted out-of-hospital births of at least two babies that ultimately died.

Midwife Eileen Stewart had her license suspended for 30 months followed by a two-year probationary period and a $2,500 fine by the New York State Education Department’s Office of Professional Discipline, the agency’s records show. Stewart did not contest the charges.

The decision was made in May but not made public until this summer.

Among Stewart’s clients was first-time Buffalo mother Morgan Dunbar, who actively labored for six hours in August 2016 before begging to go the hospital. She was running a fever, her cervix was inflamed and the contractions were unbearable.

By the time Baby Kali Ra Iman was delivered by emergency Cesarean section, he had suffered catastrophic brain damage. The family removed him from life support four days later.

He would have been 3 years old on Thursday.

The state found that Stewart failed to appropriately document Dunbar’s vital signs and to appropriately monitor her baby’s heart rate. It also determined she provided a false statement to investigators by claiming she instructed Dunbar to get out of the hot tub in which the mother was laboring.

Stewart told GateHouse Media last year she blamed Dunbar for the deadly outcome, saying Dunbar ignored her warnings about laboring in a hot tub. Stewart said she believes bacteria from the tub caused Dunbar’s infection, which compromised the baby.

“I was only involved with Morgan in what she asked me to do, which was to facilitate a home water birth for her,” Stewart said at the time. “I feel very loving and healing thoughts around Morgan. But she will not accept responsibility for what she chose to do around the labor of her baby.”

While she is glad the state finally took action, Dunbar said she was disappointed it only suspended Stewart’s license instead of revoking it.

“That’s abhorrent to me,” Dunbar said. “It’s a slap on the wrist for her, and a slap in the face to all the parents of dead children.”

Stewart declined to comment when reached by phone Friday.

In another incident, in November 2014, Stewart failed to adequately assess a client’s ability to vaginally deliver her baby, which was in a breech position, and also failed to administer penicillin within 18 hours of her water breaking.

The state did not publicly identify victims, but the 2014 incident matches details from a lawsuit against Stewart filed by Nathan and Mollie Binder. The Binders accused Stewart, who was their midwife, of negligence in the death of their newborn son. The family settled for an undisclosed sum.

Stewart also was charged by the state with practicing midwifery with gross negligence when allowing an unqualified person to independently care for and/or deliver the baby of a client.

Stewart stopped attending births in February, according to the Facebook page for her Buffalo Midwifery Services.

New Florida out-of-hospital birth reports highlight risk

By Emily Le Coz

August 17, 2019

At least six infants and one mother have died in planned out-of-hospital births with midwives since October in Florida, according to new state reports obtained by GateHouse Media.

An additional three infants and two mothers suffered catastrophic or potentially life-threatening injuries.

The reports were the first filed with the Florida Department of Health under a 2018 law meant to track adverse out-of-hospital birth outcomes. They detail 11 incidents, including two high-profile tragedies, between mid-October and mid-July and offer another glimpse into the potential dangers of delivering a baby at home or in a freestanding birth center.

A recent GateHouse Media and Herald-Tribune investigation, “Failure to Deliver,” found such deliveries are twice as likely to end in infant death and injury as those inside a hospital. And families have little recourse when something goes wrong.

Among the incidents described in the new reports are two breech babies that got stuck in the birth canal and either died or suffered severe brain injury; a baby that died in utero to a mother who was two weeks past her due date, and a lifeless baby whose mother’s water broke more than a day before she was admitted to the birthing center in active labor.

All those scenarios require midwives to consult with or transfer clients to a physician with hospital privileges, according to state regulations.

One midwife appeared in two separate, fatal incidents.

Naomi Mizrachi, of Naples, delivered a baby in April who was transferred to the hospital for breathing difficulty and later removed from life support from kidney failure, the report states.

In May, Mizrachi transferred a laboring mother whose breech baby had been stuck in the birth canal for 33 minutes. It was delivered at the hospital unresponsive and put on life support. The baby later died, the report states.

“There is not a single one in there with disciplinary actions,” said Amy Young, a lobbyist for the Florida district of the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists, which advocated for passage of the adverse-incident reporting legislation. “Where is the accountability? Where is the discipline?”

Department of Health spokesman Brad Dalton said the agency immediately reviews each report to determine if violations occurred but declined to comment on whether any triggered investigations. Such investigations aren’t public unless it determines a probable cause.

High-profile tragedies

One of the reported incidents occurred on April 29 and details a mother who died from an amniotic fluid embolism during an attempted home birth. The case matches that of 37-year-old Jacksonville woman Lauren Accurso, whose sudden death was widely reported by local and national media, including People magazine.

After passing out in a birthing tub, Accurso and her unborn son were rushed by ambulance to the hospital, where the infant was delivered by emergency Cesarean section, the family told news outlets at the time.

The boy suffered “significant brain injury due to a prolonged period without oxygen during his birth,” his father wrote on the family’s GoFundMe page. He died about two weeks later when he was removed from life support.

It’s fatal for the mother most cases, according to the Cleveland Clinic.

The infant survival rate, however, is around 70 percent, according to a study published in the spring 2016 issue of the Journal of Anaesthesiology Clinical Pharmacology.

“Neurologic status of the infant is directly related to the time elapsed between maternal arrest and delivery,” the authors wrote.

W. Gregory Wilkerson, chief of obstetrics and gynecology at University Community Hospital in Tampa, said he has seen one case of amniotic fluid embolism in his 30 years of practice.

“The lady died,” Wilkerson said, “but they saved the baby.”

The reports also include the attempted breech birth of Baby Brenden Charles Fisher in January at the now-shuttered Rosemary Birthing Home in Sarasota. During the incident, profiled by GateHouse Media and the Herald-Tribune earlier this year, midwife Jordan Shockley was able to deliver the baby’s body, but his head got stuck behind his mother’s pelvic bones.

Rosemary’s then-owner, Harmony Miller, also filed a separate report, this one related to a baby she delivered in March. The infant showed signs of breathing and heart trouble and was transferred to Johns Hopkins All Children’s Hospital in St. Petersburg where it spent a week in the newborn intensive care unit.

“Those reports make obvious we have a problem,” Wilkerson said. “I thought it would just be a couple of incidents, but there are a lot of them.”

Poor data collection

Florida’s out-of-hospital birth rate has nearly doubled from less than 1 percent of all deliveries in 2003 to nearly 2 percent in 2017, according to the most recent data from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. That’s nearly 4,000 Florida babies born at home or in a birthing center in 2017 alone.

Prior to the passage of the 2018 law, licensed midwives were required only to submit annual reports tallying hospital transfers and deaths along with a total count of clients and deliveries.

But the state struggled for years to get full compliance. Just one in three midwives submitted a report in 2016 and one in nine submitted in 2017, according to minutes of the Council of Licensed Midwifery, which receives the reports. Last year, the council achieved a 97 percent compliance rate.

The Council of Licensed Midwifery did not return a request for comment.

Birth centers also must file annual reports providing similar statistics to the state Agency for Health Care Administration.

Neither set of reports trigger automatic case reviews.

The lack of information about adverse out-of-hospital birth incidents prompted concern among some health care advocates, including retired Tampa OBGYN Robert W. Yelverton Sr., who worked with legislators to pass the law.

“Every time we tried to do something to improve the safety of out-of-hospital births we were told, ‘Where’s the data?’” said Yelverton, who serves on the state Pregnancy Associated Mortality Review Committee and was a former chair of the state district of American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists.

Now, midwives must report to the state within 15 days any incident involving maternal death, maternal hemorrhagic shock or transfusion, fetal or newborn death, certain traumatic physical or neurological birth injuries, or certain transfers of a newborn to neonatal intensive care.

The physician and hospital reports also are required for non-childbirth related incidents. They include surgical errors, accidents, and injuries involving all patients. Together, they total 973 in the same one-year time frame, according to the Department of Health and the Agency for Health Care Administration, which collect them. Neither agency could immediately provide a count of childbirth-only incidents, for comparison.

Yelverton called the new reports a good start but demanded the state now take action in cases where midwife negligence might have contributed to the adverse events.

“So now we have the data coming in, but we have no evidence that it’s being acted upon,” Yelverton said. “That was the object — not to just accumulate data, but to have something done to improve the quality of care for women of this state.”

Summit highlights dangers of out-of-hospital birth

By Emily Le Coz and Josh Salman

July 15, 2019

SANDESTIN — Mothers who lost a baby from midwife negligence during an out-of-hospital birth have long felt silenced.

Over the weekend, they regained their voice.

A diverse group of grieving parents, lawmakers, medical providers and attorneys gathered in Sandestin on Friday to discuss options for better laws and regulations surrounding the growing practice of home birth.

Organized in response to GateHouse Media’s “Failure to Deliver” investigation, the “Delivering Action Summit” was spearheaded by Athena Riley, a Panhandle attorney featured in the newspaper series, who lost her son Franklin during a tragic birth center delivery in December 2017.

Failure to Deliver: Read the Investigation

Speakers addressed the injustices that often follow an out-of-hospital birth gone wrong, while bringing new ideas for solutions.

“These are mothers and children that are not here and should be,” Riley said. “Enough is enough. Together we can make a difference, and that’s what this is all about.”

Set overlooking the blue waters of Choctawhatchee Bay, the summit attracted dozens from across the country, including representatives from Sarasota Memorial Hospital and the Fort Walton Beach Medical Center.

The attendees pushed for future reform on issues including better state reporting of midwifery care, improving informed consent for patients, requiring midwives to carry more liability insurance and mandating local physician partnerships, among other proposals.

At least one Florida lawmaker vowed to make the issue a top priority during the next legislative session.

“It energized me to want to take some action in terms of strengthening laws,” said Rep. Mike Hill, R-Pensacola, who attended the event. “Something definitely needs to be done.”

Home births and birth center deliveries have exploded in popularity across Florida, part of a national movement among mothers seeking a more natural approach.

During the past two decades, out-of-hospital deliveries in Florida spiked more than 125% — and nowhere is that trend more pronounced than Sarasota, where the out-of-hospital birth rate is more than double the statewide average.

The GateHouse Media and Sarasota Herald-Tribune’s “Failure to Deliver” investigation found these deliveries are up to eight times more deadly than traditional hospital births. And after unexpected tragedies, families are left with little recourse for justice.

Most out-of-hospital midwives lack nursing degrees. Some can’t administer drugs. Few carry adequate lifesaving equipment. Many are afraid to call 911 when emergencies arise. More than a dozen states don’t regulate them at all.

“It’s a huge problem nationwide,” said Ervin Yen, an anesthesiologist and former state senator from Oklahoma, who previously introduced midwife legislation. “Every state needs to tighten up.”

A former prosecutor presented ideas on how more negligent midwives could face criminal charges in future instances of fatal misconduct.

Lawyers also talked about ways to improve the civil side. Experts estimated it takes more than two years and $122,000 on average to pursue a medical malpractice lawsuit.

But in Florida, midwives are required to carry only $100,000 of insurance per incident. As a result, few families can seek justice in court.

And it’s rare for the state’s licensing board to take any serious action. From 2008 through 2017, Florida formally pursued discipline in just 36 of the 170 midwifery complaints — including at least 10 involving fatal incidents. The state revoked only one license during that time, although six other midwives voluntarily surrendered theirs after facing allegations.

For years, it was voluntary for midwives in Florida to submit annual reports. Even now, the forms documenting patient care and adverse incidents are often missing or incomplete.

“In Florida, we have a real mess for patients,” said Virginia Buchanan, an attorney who represents Riley and spoke at the summit. “The law is one-sided and provider protective.”

Experts say events like the “Delivering Action Summit” and future planned efforts will help mothers make better decisions about the dangers of home birth, while helping legislators find ways to protect them.

“The number of lives lost is huge,” said John Fisher, an attorney who represents a father who lost his wife and son during an attempted home birth. “It’s a war of truth and information. That’s what today is all about: educating mothers and fathers about the risks of a home delivery ... it’s not really a choice if the mother knows little about the true risks.”

Are midwives out of reach for rural patients?

By Lucille Sherman

May 19, 2019

Non-nurse midwives, who provide maternity care and deliver babies in homes and freestanding birth centers, have lobbied lawmakers for licensure and other rights across the country by promising to serve rural areas. But a GateHouse Media data analysis of more than 3,000 non-nurse midwives and freestanding birth centers shows the majority of them are clustered in cities and suburbs already served by hospitals with obstetric care units.

Sarasota’s Rosemary Birthing Home to close

By Emily Le Coz, Josh Salman and Lucille Sherman

Apr. 16, 2019

A Sarasota birthing center profiled as part of a nine-month investigation by GateHouse Media and the Herald-Tribune will soon close its doors.

Rosemary Birthing Home made the announcement on its website this week. The decision follows a series of adverse outcomes culminating with an incident in January that severely injured a baby boy after a midwife attempted to deliver him breech.

The owner of Rosemary was previously trying to sell the business to the midwife involved in that January incident, according to a source. But citing financial concerns, the center will close instead.

Miller also filed notice of the closure with the state.

“Hearing the news that Rosemary Birthing Home is closing is a huge victory,” said Riva Majewski, who lost her daughter during an attempted home birth with a Rosemary midwife in 2016. “This brings my husband and I a great sense of relief and finally after three years, a feeling of justice for our precious Baby V.”

Harmony Miller, the owner of Rosemary, did not return calls, emails or texts seeking comment Tuesday.

On its website, the birthing center said it would continue serving clients who deliver before May 12, but referred all others to the Birth Center of St. Pete and Birthways Family Birth Center in Sarasota. Both centers have waived their registration fees for families who already paid them to Rosemary.

Birthways has already begun receiving clients as a result of the announcement, said its owner, Christina Holmes, also a state-licensed midwife.

Rosemary drew ire from some area obstetricians, who say they were overwhelmed with the number of emergency hospital transfers originating at the birthing home.

From 2007 through the end of 2017, midwives at Rosemary delivered 396 babies inside the birth center and called for hospital transfers 130 times, according to a review of annual reports filed with the Agency for Health Care Administration.

Midwives at the birth center also were calling 911 and requesting paramedics to be on “standby” — leading to a rift with local first responders.

“How many examples of bad outcomes do we need before the community, medical leadership and state leadership go ‘Now we get it’?” Kyle Garner, a physician with Gulf Coast Obstetrics and Gynecology, previously said of Rosemary’s care. “How many major complications are we going to tolerate in Sarasota?”

The birth home has a troubled history that includes at least three infant deaths, including that of Baby V, and a rash of hospital transfers. At least one of the deaths was because of a congenital heart defect and not preventable, according to that child’s mother.

In the most recent incident, which was profiled by GateHouse Media and the Herald-Tribune, midwife Jordan Shockley attempted to deliver a footling breech baby on Jan. 30 at the birth center instead of immediately consulting a physician or transferring the laboring mother to the hospital, as state regulations require.

Brenden Charles Fisher was delivered with no pulse or heartbeat and had to be revived at the hospital. He suffered severe brain damage and spent several weeks at Johns Hopkins All Children’s Hospital in St. Petersburg.

The state Department of Health launched a preliminary investigation into the incident, according to the mother, Paris Bean, who said she received calls from the agency seeking information. The department declined to confirm or deny such an investigation.

When the joint investigation, “Failure to Deliver,” was published in November, Bean said, she defended the birth center. After her experience, she said it needed to be shut down.

“I have chills from all these moms that went through a similar situation,” she said. “This can’t happen to anyone ever again.”

Rosemary Birthing Home opened in 2003 and was originally owned by state-licensed midwife Heidi Dahlborg. Miller took over in 2007. She was in the process of transferring ownership to a yet another midwife when the latest incident occurred, according to the website.

“For the last nine months we have worked toward that end,” the website said. “That is no longer happening.”

Although the website does not name the other midwife, Holmes said Shockley was the one preparing to take over the business.

Shockley started training at Rosemary as a student midwife while attending the Florida School of Traditional Midwifery, according to an earlier version of the birth center’s website. When she received her state license in November, she became a permanent part of the team.

Prior to joining Rosemary, Shockley had trained under Holmes, who said she had several concerns about the student midwife and “dismissed her” from her internship.

Holmes said she shared those concerns with both the school and with Miller.

No one at the Florida School of Traditional Midwifery, based in Gainesville, could be reached for comment late Tuesday.

Shockley also did not return a call for comment Tuesday.

Read more:

Failure to Deliver - The Crisis: Amid tragedy, a Florida county grapples with home birth dangers

GateHouse Investigation: Failure to Deliver - How the rise of out-of-hospital births puts mothers and babies at risk

Attempted out-of-hospital birth takes tragic turn for new parents

By Emily Le Coz, Josh Salman and Lucille Sherman

Feb. 22, 2019

Paris Bean checked into Rosemary Birthing Home before the sun rose on the last Wednesday in January, excited to deliver her first child.

Paris Bean checked into Rosemary Birthing Home before the sun rose on the last Wednesday in January, excited to deliver her first child.

Two weeks past her original due date and plump from pregnancy, the 23-year-old lumbered into the freestanding birth center with her longtime partner, Jason Fisher.

The couple carried a load of clothes and blankets for the baby, a birthing kit for the midwife, several bags of ice and two homemade casseroles — enough for 25 people — to feed the entire birthing team that they expected to rally around them.

But just one person was there at the time, Bean and Fisher said.

Newly licensed midwife Jordan Shockley welcomed the couple and ushered them into a private birthing room on the first floor of the converted, historic home.

It was just past 7 a.m.

Outside, the sun cast its first light on what would be their son’s birthday. A day that turned to horror after the baby went into cardiac arrest, respiratory failure and ultimately severe brain damage from which he may never fully recover, according to the midwife’s notes and records, an EMS report, and interviews with the family and a hospital official.

A previous story in the Herald-Tribune inaccurately stated, based on information from three sources, that the baby had died. [See correction here]

Brenden Charles Fisher is still alive.

He is at Johns Hopkins All Children’s Hospital in St. Petersburg. He has a tube in his nose delivering a steady flow of oxygen. A tube in his leg administers fluids, nutrients and anti-seizure medication. Another tube in his throat provides tiny doses of breast milk in an attempt to wake up his digestive system.

He cannot swallow. His parents and nurses take turns suctioning saliva from his throat and mucous from his nose.

He doesn’t cry. His only sounds so far came from a bout of hiccups.

His long-term prognosis is unclear.

It is the latest incident at Rosemary Birthing Home, profiled last year as part of a nine-month investigation by GateHouse Media and the Herald-Tribune into the dangers of out-of-hospital births.

One of the area’s two birth centers, Rosemary has a troubled history that includes at least three deaths and a rash of hospital transfers. At least one of the deaths was due to a congenital heart defect and not preventable, according to the child’s mother.

The owner of Rosemary did not respond to an email seeking comment for this story.

When the investigation, called "Failure to Deliver,” was published in November, Bean said, she defended the birth center. Now, she said, it needs to be shut down.

“I have chills from all these moms that went through a similar situation,” she said. “This can’t happen to anyone ever again.”

‘So many things were done incorrectly’

Brenden Charles Fisher was a foot-first breech baby.

Most babies flip into a head-down position in the last weeks of pregnancy. But a small fraction do not flip and either their buttocks or feet point toward the birth canal instead. Most breech babies are delivered by cesarean section.

Shockley did not know the baby was breech when Bean checked into the birthing home that morning in active labor.

Nor did she know one hour later when she performed a vaginal exam and said she felt the baby’s head, Bean said.

She only discovered it when, after 2 p.m., she broke Bean’s water and felt a foot, according to Shockley’s notes, which Bean provided to the newspaper.

Shockley was reached by phone Thursday morning but said she was not able to immediately comment despite receiving Bean’s written consent to disclose client information. She said would call back but did not do so. She did not respond to two additional attempts to reach her.

The midwife’s own notes reflect she did not follow several state midwifery regulations prior to the baby’s traumatic delivery.

Florida regulations require midwives to perform an initial assessment at the onset of labor, including a vaginal examination to assess the baby’s presentation and position. Shockley’s notes show she did not do this. She said the exam was “declined.”

Florida regulations require midwives to refer their clients to a physician with hospital privileges if the baby has not flipped to the head down position after the 37th week of gestation. Shockley did not do this, according to her prenatal notes. There’s no mention of the baby’s position at the post-37-week appointments.

Florida regulations require midwives to refer their clients to a physician with hospital privileges if the baby’s gestational age is between 41 and 42 weeks. Shockley did not do this, according to her prenatal notes. She altered the due date instead, pushing it back by nine days less than a week before Bean was projected to give birth.

Florida regulations require midwives to consult with or transfer their clients to a physician with hospital privileges if the baby is breech during labor. Shockley did not do this, according to her labor notes. She attempted to deliver the baby herself at the birthing center.

“So many things were done incorrectly with this birth,” said Paris Bean’s mother, Nikki Bean.

‘I just can’t believe this all happened’

When Shockley felt the foot and told Bean the baby was breech, the laboring mother said she cried because she was scared. But Shockley reassured her that it wasn’t a problem, Bean recalled.

“She told me to push, and we could have the baby, and everything would be OK,” Bean said. “I just can’t believe this all happened. We were sold on this beautiful experience. I trusted her.”

Shockley noted in her report that she had an “urgent discussion” with Bean about going to the hospital at that point, but that Bean refused. Both Bean and Fisher dispute that account. They said they never refused hospitalization and would have willingly gone then if their midwife advised them to do so.

Shockley then dialed an unidentified person for advice, the couple said. When she hung up, she called 911. Her notes from the labor report state that she “activated EMS, gave report of fetal breech presentation with needs for urgent support.”

An audio recording of the 911 call sounds anything but urgent.

“I have a mom in labor, everything’s fine, but her baby is breech,” Shockley told the dispatcher. “We broke her water and found a foot, so we kinda want 911 on ... she’ll have a baby by the time they get here, but just to have them here.”

Paramedics arrived three minutes later, according to the EMS report. Some gathered in the hallway, others in the birthing room, as Shockley instructed the mother to push, Bean and Fisher recalled.

“The main EMT said, ‘She shouldn’t push. We need to go right now,’” Fisher said. “But Jordan said, ‘No, just push.’ The arguing went on for it seems like forever.”

Neither the midwife’s labor notes nor the EMS record mentions an argument. The EMS record states simply: “Decision made to continue delivery at birthing center.”

But it appears paramedics broke their own protocol, established in 2015 in response to previous such incidents with out-of-hospital midwives.

“Licensed midwives attending childbirths at birthing centers or private residences are not healthcare professionals,” according to the Sarasota County EMS Handbook for Community Protocols. “Respond, assess, stabilize and transport the mother and/or newborn to an appropriate Resource Hospital. Staging at the birthing center and engaging in discussions with the midwife are not authorized.”

Sarasota Fire and EMS Chief Michael Regnier refused to answer questions directly related to that incident. He said each case is different.

The EMTs stayed at the birthing center for nearly 30 minutes, records show, while Shockley attempted to the deliver the baby herself.

According to her labor notes:

At 2:54 p.m., a foot emerged.

At 2:56 p.m., both feet and calves emerged.

At 2:59 p.m., Shockley claims she again advised her client of the need for urgent transport. Bean and Fisher strongly deny the midwife ever encouraged them to go to the hospital.

At 3 p.m., the buttocks emerged covered in meconium — the baby’s first stool.

At 3:02 p.m., the midsection emerged.

At 3:07 p.m., the arms emerged.

At 3:08 p.m., the head remained stuck and Shockley again claims she expressed an urgency to transport. Again, the couple denied this.

At 3:10 p.m., Bean is moved to the stretcher to begin transport to Sarasota Memorial Hospital.

‘There was a protocol, and I broke it’

Bean was on her back on the stretcher with a portion of her baby dangling from her vagina. Shockley got on the stretcher with her. Paramedics loaded them into the ambulance and left Rosemary at 3:13 p.m.

While en route to Sarasota Memorial Hospital, paramedics noticed the baby’s exposed umbilical cord stopped pulsing, the report states. This means it was no longer delivering blood and oxygen to the brain. They also discovered the mother’s placenta had detached.

They cut the cord and began chest compressions on the baby, with his head still lodged behind his mother’s pubic bone. Bean said she reached out and held her son’s hand.

The baby went into cardiac arrest at 3:18 p.m., according to the EMS report.

Back at the birth center, Fisher was standing in a daze on the street, he said. The ambulance had left him behind. He was covered in blood and meconium, unsure what to do. Eventually, someone took him to the hospital.

Mother and midwife arrived at Sarasota Memorial Hospital at 3:21 p.m., according to hospital spokeswoman Kim Savage, who had permission from the family to discuss their case with the media.

Shockley went into a waiting area while staff wheeled Bean into a room. After several attempts to have Bean push out the baby, the staff gave her a third-degree episiotomy — cutting her from the anus to the vagina — and pulled out her baby.

It was 3:29 p.m. Brenden was limp and unresponsive, Savage said in an email.

“He was in cardiac and respiratory failure at birth. His APGAR score at one minute after birth was zero,” Savage said in the email. “It increased to a 3 within five minutes and remained a 3 at 10 minutes.”

An APGAR score rates the baby’s condition at birth on a scale from 0-10, with 0 being lifeless and 10 being healthy. Midwives are required to submit that information to the state on their annual reports. Shockley noted in her labor report the baby’s 10-minute score was 4.

“His neurologic assessment was abnormal and consistent with severe hypoxic encephalopathy,” Savage added, referring to the brain damage that occurs when a person is deprived of oxygen.

The neonatal intensive care team resuscitated the baby and restored his heartbeat, but he was unable to breathe on his own and needed to be intubated, Savage said in the email. The team also began immediate cooling treatment, lowering his body temperature in an attempt to reduce brain damage. He was transferred three hours later to Johns Hopkins All Children’s Hospital in St. Petersburg.

“They told me before they took him,” Fisher said, ”If he makes it through the night, he will never wake up again. He’s totally brain dead.’”

While sitting in the hospital waiting room with Shockley, Fisher said he asked her what happened.

“She told me, ‘There was a protocol, and I broke it,’” he said.

Bean’s sister, Sadiee Bean, said she asked the midwife the same question later that night.

“She was telling me a bit of what happened and said, ‘I’ve seen so many beautiful breech birth videos on Instagram, and I just thought this was going to be one of those,’” said Sadiee Bean. “She was very emotional. She kept saying, ‘This is the worst night of my life.’”

‘I’m very frustrated with Rosemary’

Shockley had been Sadiee Bean’s midwife, too, delivering the woman’s son in October as an assistant to licensed midwife Harmony Miller, who owns Rosemary Birthing Home. It was an uncomplicated delivery, and the baby was born healthy and pink.

At the time, Shockley was a still a student midwife.

State regulations require student midwives be under the direct supervision of a preceptor during their clinical training, including when they conduct prenatal visits and deliver babies. Both Sadiee and Paris Bean said Shockley did all their prenatal appointments alone.

Shockley received her midwifery license from the state on Nov. 5, less than three months before attempting to deliver Paris Bean’s breech baby without another licensed midwife present.

The Bean sisters knew Shockley was a student but assumed everything had been done by the books.

Bean chose to deliver her baby at Rosemary on the recommendation of friends and family, including her sister, who chose an out-of-hospital birth after a bad experience at Sarasota Memorial Hospital two years ago this month.

The hospital staff were bossy and rude, refused to let her change positions, and caused her to break her tailbone during delivery, the family said.

“While I’m very frustrated with Rosemary, I do want to express that the hospital’s rigid rules and cold practices and standards are why so many mothers are seeking birthing home births,” said their mother, Nikki Bean. “These birthing homes wouldn’t be in business if hospitals were doing a better job of meeting these mothers’ needs.”

‘I just knew something wasn’t right’

This is not the first time midwives with Rosemary Birthing Home failed to adequately determine a baby’s position, according to state records that show at least one other instance since 2016 when an “unplanned breech” delivery occurred. Birth center owner and licensed midwife Harmony Miller oversaw that delivery, records show.

Miller also oversaw the attempted delivery of another unplanned breech baby in January 2014, said Jennifer Smith, who accompanied her pregnant daughter to the birthing home where she labored for hours without progress.

“I just knew something wasn’t right,” Smith said.

Smith said she eventually encouraged her daughter to go to the hospital over the objections of Miller, whom she said had assured them everything was fine.

When they arrived at Sarasota Memorial Hospital, staff confirmed the baby was in the breech position and needed to be delivered by C-section, Smith said. Baby Cooper was born on New Year’s Day, pink and healthy.

Annual reports submitted to the state by Rosemary Birthing Home show a patient transferred to the hospital during labor for failure to progress the same day.

Smith said she reported the incident to the Florida Department of Health, which regulates licensed midwives under its Council for Licensed Midwifery. But she said she never heard back.

“How did she not know this baby was breech?” Smith said. “My concern is that she doesn’t pay attention to her patients.”

Rosemary Birthing Home opened in 2003 and changed ownership in 2007. Its midwives offer prenatal care, labor and delivery, postnatal care and family education. Deliveries occur both inside the birth center and at the clients’ homes.

It is one of two freestanding birth centers in Sarasota. Birthways Family Birth Center is the other. Together, they called 911 for more emergency transfers than almost anywhere else in Florida. During the past three years, one-third of local home and birth center deliveries ended at the hospital.

The emergencies prompted paramedics to change how they respond to calls from birth centers, while distraught staff at Sarasota Memorial Hospital began tracking the transfers themselves.

“Many of these women have been in labor for three or four days,” John Abu, a physician who heads Sarasota Memorial’s emergency obstetrics, told the newspaper last year. “They’re exhausted. They’re terrified. They have a fever and higher rate of infection.”

‘They essentially told me he would be a vegetable’

Nikki Bean raced from Parrish to Sarasota Memorial after getting a text from Fisher that something had gone wrong during her daughter’s delivery.

When she arrived, her daughter was in surgery having her episiotomy laceration repaired and her grandson was in the newborn intensive care unit.

Frantic for an update, she texted the midwife.

“I’m here with the baby,” Shockley replied.

“Is the prognosis still the same?” Nikki Bean texted.

“Yes,” Shockley said.

“No brain activity. Is that what they’re saying,” Nikki Bean asked.

“Yes,” Shockley replied, before informing her that the baby has “always had a heart rate.”

The text did not disclose that the baby had gone into cardiac arrest and the hospital performed chest compressions to restore his heartbeat after he was delivered.

Three hours after his emergency delivery, the baby was transferred to All Children’s Hospital by helicopter. Fisher was given the option to accompany his son or stay with his wife, who needed to recover from her surgery overnight at Sarasota Memorial.

“I stayed with Paris,” he said, “since they essentially told me he would be a vegetable.”

Shockley visited her client the next morning in Bean’s hospital room. She brought flowers, snacks, kombucha, coconut water and amethyst. Nikki Bean and Fisher had to leave the room. They said they couldn’t stand to look at her.

“When she came up to talk to us, I feel like she was looking for somebody to comfort her, to make her feel better about the decisions that she had made,” Nikki Bean said. “My jaw just dropped. I felt like I was talking to a high school student, not a medical professional or someone who was capable in her skills.”

Shockley has continued to reach out to Paris Bean in the weeks since the incident, but Bean said she has stopped responding. She no longer wants to communicate with the midwife. She said she is angry, upset, betrayed.

“The whole thing is just so sad and ridiculous,” Bean said. “Even all the doctors here say it’s 100 percent because of how the birthing went.”

‘This whole thing was avoidable’

Bean and Fisher have spent every day since then by their son’s side at All Children’s Hospital, where he remains connected to machines to keep him sustained.

Baby Bean, as his parents affectionately call him, has made steady improvements since Feb. 7, when doctors recommended they consider removing life support because he had no brain activity.

That was on a Thursday.

The couple took the weekend to think it over and wait for the results of the next MRI. The results came back that Monday: There was brain activity.

In another sign of good news, Brenden started to breathe some on his own. So the care team gradually reduced the ventilator until they were able to shut it off entirely. The oxygen he receives now keeps his lungs expanded but does not breathe for him.

“Until he started making improvements, I was feeling so guilty and so awful about myself,” Fisher said. “Now we’re just focused on him getting better. We’re taking it day by day.”

Best-case scenario, doctors told them, is that Brenden goes home in another six weeks. What that looks like when they get there, no one can say. But nobody mentions the worst-case scenario anymore.

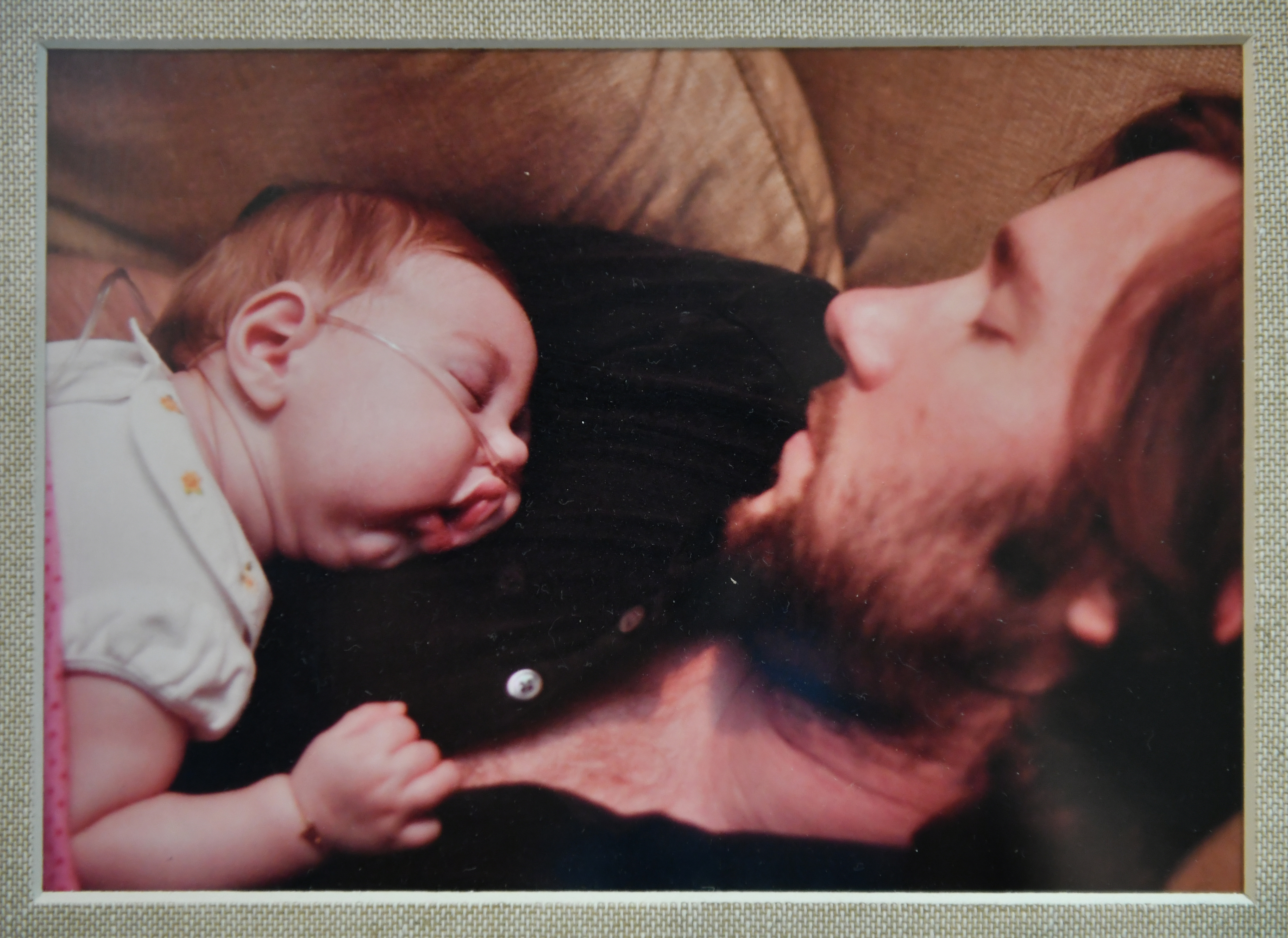

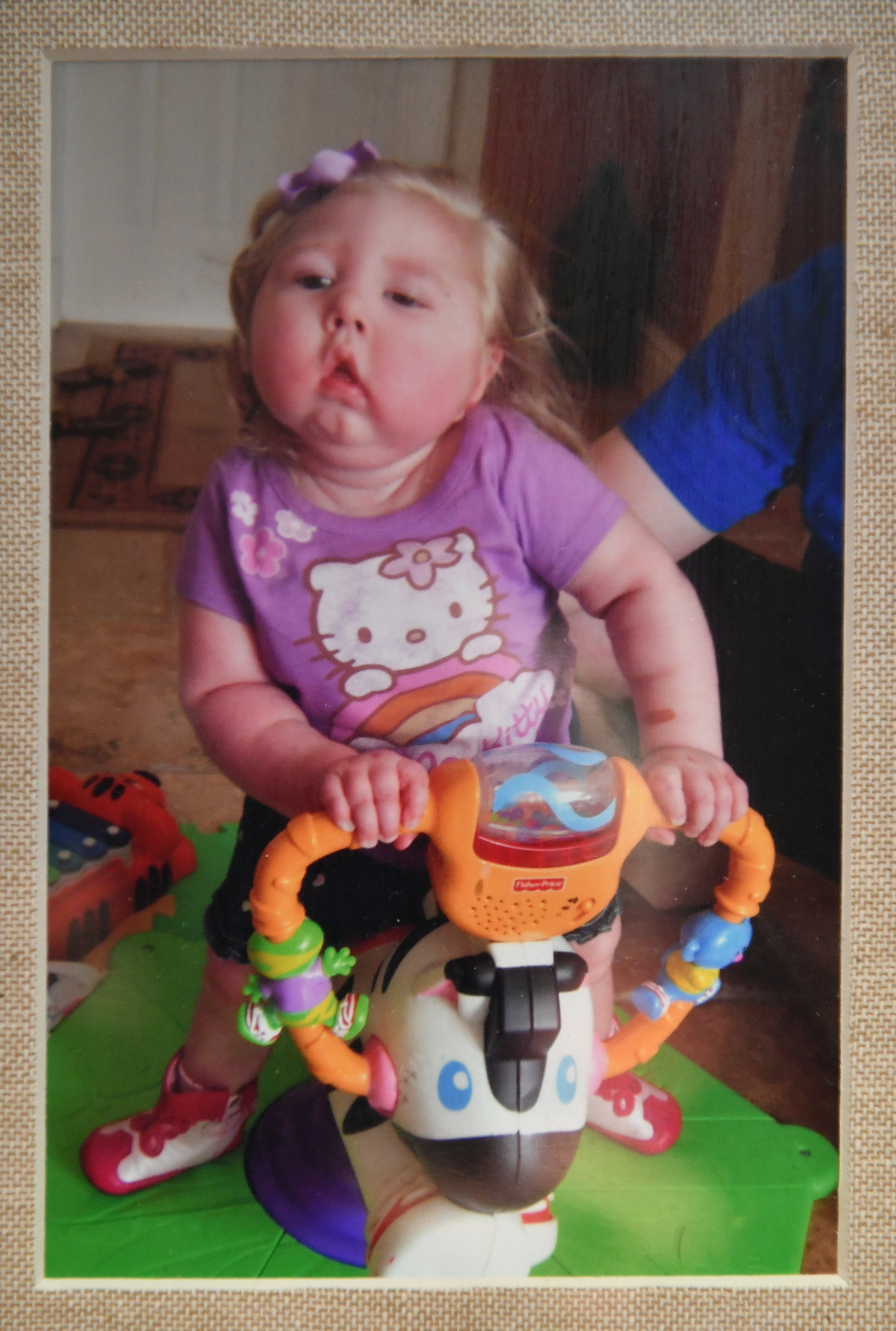

Brenden was 9.9 pounds and 22 inches at birth. With deep blue eyes and a shock of red hair, he resembles a photo of his infant father taken 37 years ago.

“We’re Irish,” Fisher said with a grin.

Fisher was sitting in the dimmed room near his son’s crib Tuesday morning. Every few minutes, he rose to check the baby, who lay silently on a blanket next to a crocheted octopus gifted by a hospital volunteer.

Bean sat nearby, looking tired but determined. The couple hasn’t been home in three weeks. They spend all day at the hospital and sleep at the Ronald McDonald House down the street.

“We are well taken care of here,” Bean said about All Children’s Hospital. “We feel very blessed. They all love Brenden. They hold his hand and they come in and sing to him and play guitars. They all check up on us and make sure we’re OK. It’s nice to be surrounded by such kind people.”

A nurse entered the room and smiled. She approached the crib and swaddled Brenden in a blanket, then handed him to his mother. Bean cradled the baby as the nurse attached the tube in his mouth to a little machine that drips breast milk into his stomach. Bean has been pumping her milk for Brenden, hoping one day to feed him herself.

She looked down at her son and smiled.

“Once we get home there will be an emotional release,” she said, “but I have had to hold my emotions in for him and focus on him and his growth.”

They closed their business and sole source of income, The Green Bean Coffee House on Bradenton Road in Sarasota, because neither one wants to leave their baby’s side. They don’t know how they’ll manage financially, especially once the medical bills roll in.

They started a GoFundMe page to help cover Brenden’s medical care and physical therapy, as well as to help them reopen the coffee shop when they return. The goal is $100,000. They had raised $1,226 as of Thursday.

Bean and Fisher try to remain positive. They want to believe their son will keep beating the odds and live a full life. But the whole family has a long road ahead, one fraught with uncertainty, unanswered questions and a lot of emotions to process.

“Every time I look at my grandson I well up with so much anger,” Nikki Bean said, “because this whole thing was avoidable had Jordan followed the rules.”

No justice for empty-armed parents

By Josh Salman and Lucille Sherman

Feb. 16, 2019

Two midwives profiled in a GateHouse Media investigation into out-of-hospital births will face no future punishment after babies died under their care.

Florida’s Board of Nursing restored the credentials this month for Cynthia Denbow, a certified nurse midwife in the Panhandle who failed to call for a timely hospital transfer after learning of a baby’s breech position during an attempted birth center delivery in December 2017, according to the state’s complaint.

Licensed midwife Ivy Hummon also can continue delivering babies with no consequence for her role in the unexpected death of a baby girl during a March 2016 home birth in Sarasota, the baby’s family was recently notified.

Experts point to the preventable deaths of Baby Franklin and Baby Vayden as further evidence of a system with no accountability for midwives following tragic out-of-hospital birth outcomes.

Like most states, Florida has rules that regulate both nurse and non-nurse midwives. But physicians, hospital administrators, medical malpractice attorneys and a growing group of grieving parents say the state has not done enough — and continues to stand pat while babies die.

“We see a problem holding (midwives) accountable when substandard care is practiced,” said Kyle Garner, a physician with Gulf Coast Obstetrics and Gynecology in Sarasota. “But we are powerless to affect it. There is no political follow-through.”

Home births and birth center deliveries have exploded in popularity across Florida, part of a national movement among mothers seeking a more natural approach.

During the past two decades, out-of-hospital deliveries in Florida spiked more than 125 percent — and nowhere is the trend more pronounced than Sarasota. The county’s out-of-hospital birth rate is more than double the statewide average.

But an ongoing GateHouse Media and Sarasota Herald-Tribune investigation found these deliveries are up to eight times more deadly than traditional hospital births. And after unexpected tragedies, families are left with little recourse for justice.

“We have seen more of these out-of-hospital births over time, but we’re in a tough situation,” said Thomas Searle, an obstetrician with OB-GYN Associates in St. Augustine, a city that’s experienced at least three out-of-hospital birth tragedies in recent years.

“The hospitals are obligated to pick up the pieces,” he said. “We have no leverage — even in our local community — to change the climate. We just have to wait until they bring their clients to us, and that’s usually through the ER.”

Panhandle midwife returns to work

Athena Riley and her husband had been trying to conceive for more than four years with no luck.

So when the couple from Destin learned they were expecting their first child in 2017, they thought it was a miracle.

“We were just so happy and excited,” Riley said. “It was just such an exciting time for us to know we could bring a child into this world.”

They named their son Franklin, like his father, grandfather and great-grandfather. The expectant couple went on nature walks, did prenatal yoga and took trips to the beach. They considered it a “dream pregnancy.”

But everything changed when they checked into the birth center on a cold and rainy December night in 2017.

The state’s complaint says Denbow did not perform a timely vaginal examination, was late to call for a hospital transfer and encouraged Riley to continue pushing after discovering the baby’s breech position. Physicians at Fort Walton Beach Medical Center tried to perform an emergency cesarean section and rushed the baby to the neonatal intensive care unit for resuscitation. They could not save the little boy.

The Florida Department of Health secured an emergency suspension against Denbow’s nursing license last year, and the midwife closed her birth center, Gentle Birth Options.

In its complaint, the state also says the midwife made false “representations” to the expectant parents regarding her hospital privileges and physician partnerships.

But an administrative law judge recommended in late December that the state dismiss its case against the Niceville midwife, ruling there was not enough “clear and convincing evidence” to uphold the allegations.

The judge was especially critical of the state’s witness, an expert on hospital labor and deliveries unfamiliar with birth center protocols. Most certified nurse midwives in Florida work alongside doctors in hospitals, Denbow being an exception.

Florida’s Board of Nursing followed the judge’s recommendation this month.

Suzanne Hurley, an attorney representing Denbow and a home birth advocate, previously told GateHouse Media the parents were just “looking for someone to blame” and that their baby would have died anyway. She tried to stop the grieving mother from making a victim’s statement before the nursing board and pushed responsibility onto the hospital.

“I’m very disappointed in the Department of Health for filing this case,” Hurley told the board at a Central Florida golf resort.

Riley also filed a medical malpractice lawsuit against Denbow, which was settled for an undisclosed sum in January.

She said she felt helpless as she left the Board of Nursing meeting, sobbing in her husband’s arms as the midwife was told she could return to work.

“There is no question — zero question — that this baby would have survived had a timely C-section been done,” said Riley’s attorney, Virginia Buchanan, in an earlier interview. “There was nothing wrong with their baby — he was healthy and full term.”

Sarasota midwife to face no punishment

It took Riva Majewski more than two years to face her trauma and file a formal complaint against midwife Ivy Hummon.

When Majewski completed the paperwork, she was surprised to learn in January that the state had already reviewed her daughter’s death — and found no wrongdoing or negligence.

Majewski chose a home birth with midwives from Rosemary Birthing Center in Sarasota to deliver her expectant daughter, Vayden. An ode to the way her mother gave birth to her some three decades earlier, Majewski planned a water birth in her Sarasota condominium.

During the March 2016 delivery, more than three hours passed before the midwives checked Majewski’s cervix, police records show. Baby Vayden’s shoulders were stuck in the birth canal. But Hummon let the first-time mother continue laboring for hours without calling emergency responders for help.

When they finally pulled out the baby girl, she was blue and limp. Vayden never cried or took a breath.

Majewski, who provided her birth records to GateHouse Media, says midwives at the birth center were not transparent about the potential risks associated with her weight and the size of her fetus, warning signs for shoulder dystocia. They also did not report Majewski and her baby’s hospital transfers to the state as required, records show.

“Just as we were welcoming our beautiful, most perfect baby girl into the world, we unexpectedly had to say goodbye,” Majewski wrote her friends on Facebook. “Our hearts are shattered. I cannot even attempt to know how to deal with the tragic loss of my precious daughter.”

Following a GateHouse Media investigation of her daughter’s death, Majewski decided to formally complain against Hummon, who had previously been on licensure probation over poor patient care due to a prior, unrelated incident.

The Department of Health sent a letter to Majewski in late January that a complaint had already been made on her behalf.

“The information was reviewed by a consultant that is licensed and knowledgeable of the acceptable standard of care for the practitioner,” according to the Jan. 29 letter from Department of Health investigation specialist Megan Gutsch. “After careful review of the records provided, the consultant determined the midwife in question followed the standard of care with concerns to shoulder dystocia.”

But the state never contacted Majewski to hear her side of the story. She had no idea state regulators were even looking into it.

The letter also said the department’s “Consumer Service Unit” had no authority over the midwife’s failure to report Vayden’s death.

Because the state did not open an administrative complaint, the details of the review are sealed and confidential — even to the mother.

“If there are any complaints that are still being investigated or have been closed without a finding of probable cause then the department can neither confirm nor deny (the) existence of those complaints and any information regarding the case and investigation is confidential and exempt from public record,” DOH spokesman Brad Dalton said in an email statement.

Rosemary owner Harmony Miller did not return phone calls and emails for this story. She previously declined to comment on the details of Majewski’s delivery, citing federal patient privacy laws.

Hummon, the midwife overseeing Majewski’s home birth, also could not be reached.

Majewski, meanwhile, is still looking for answers.

“I’m not OK with that letter,” she said. “That can’t be the end of this.”

“I don’t even know what else to do.”

‘Shame on our health system’

Experts say the two cases illustrate broader problems with the state’s inability — or unwillingness — to hold midwives accountable following tragic outcomes.

The Florida Department of Health oversees certified nurse midwives through its Board of Nursing. The state regulates non-nurse midwives through its Council of Licensed Midwifery. Physicians, lawmakers and other medical industry experts say the system is toothless.

Since fiscal year 2007, patients have filed 170 complaints against licensed midwives — for issues ranging from administering prescriptions without proper authorization to patient injuries and fetal deaths.

It was rare for the state to take any serious action.

While 112 cases were considered “legally sufficient,” just 36 administrative complaints were opened, according to a review of Medical Quality Assurance Annual Reports.