Easton's success built on 'emotional connection' with patrons

It began with a huge gamble on a huge slice of land.

But 20 years later, Easton Town Center draws nearly 30 million visitors a year, sells more than $1 billion in food and merchandise, has drawn national awards and changed the face of Ohio retail.

Though Easton's ride hasn't been perfect, developers can claim victory over the skeptics.

"It’s more than what we imagined 20 years ago," said Leslie H. Wexner, chairman of L Brands and the driving force behind Easton. "It’s bigger and it's better."

And there were plenty of skeptics.

"That’s an understatement," Wexner now says with a laugh. "People thought we were nuts."

The idea

Easton Town Center will celebrate its 20th anniversary in a week, but its origins are far older. L Brands began assembling the future Easton property in the mid-1980s for a potential distribution center and offices. After opening a call center for Victoria's Secret on the property in 1992, Wexner reconsidered the future of the land. With the help of his development partner, the New York-based Georgetown Company, Wexner began exploring retail uses for the site.

Their travels took them to shopping centers throughout the country, including a place called CocoWalk in Miami, developed by Yaromir Steiner, a native of Turkey.

Wexner liked CocoWalk's open design, which mixed restaurants and shops in a "lifestyle center" style that had been a hit in places such as Mizner Park in Florida and the Irvine Spectrum Center in Southern California.

"The pattern of the shopping center was so much of a cookie cutter, with a two- or three-story air-conditioned building with three, four, five, six department stores," Wexner recalled. "I believed that one day we would look at that real estate and say, 'That’s obsolete.' What would be the next turn of the wheel?"

Inspired by CocoWalk and others, Wexner made two crucial decisions: leave some stores open to the elements and move them off the highway to create what could become a town center.

"Les had the vision of saying, 'This could be more, this can be the driver of the entire city,' " said Adam Flatto, Georgetown's president and chief executive officer. "We came up with this notion of an urban district, Columbus’ midtown."

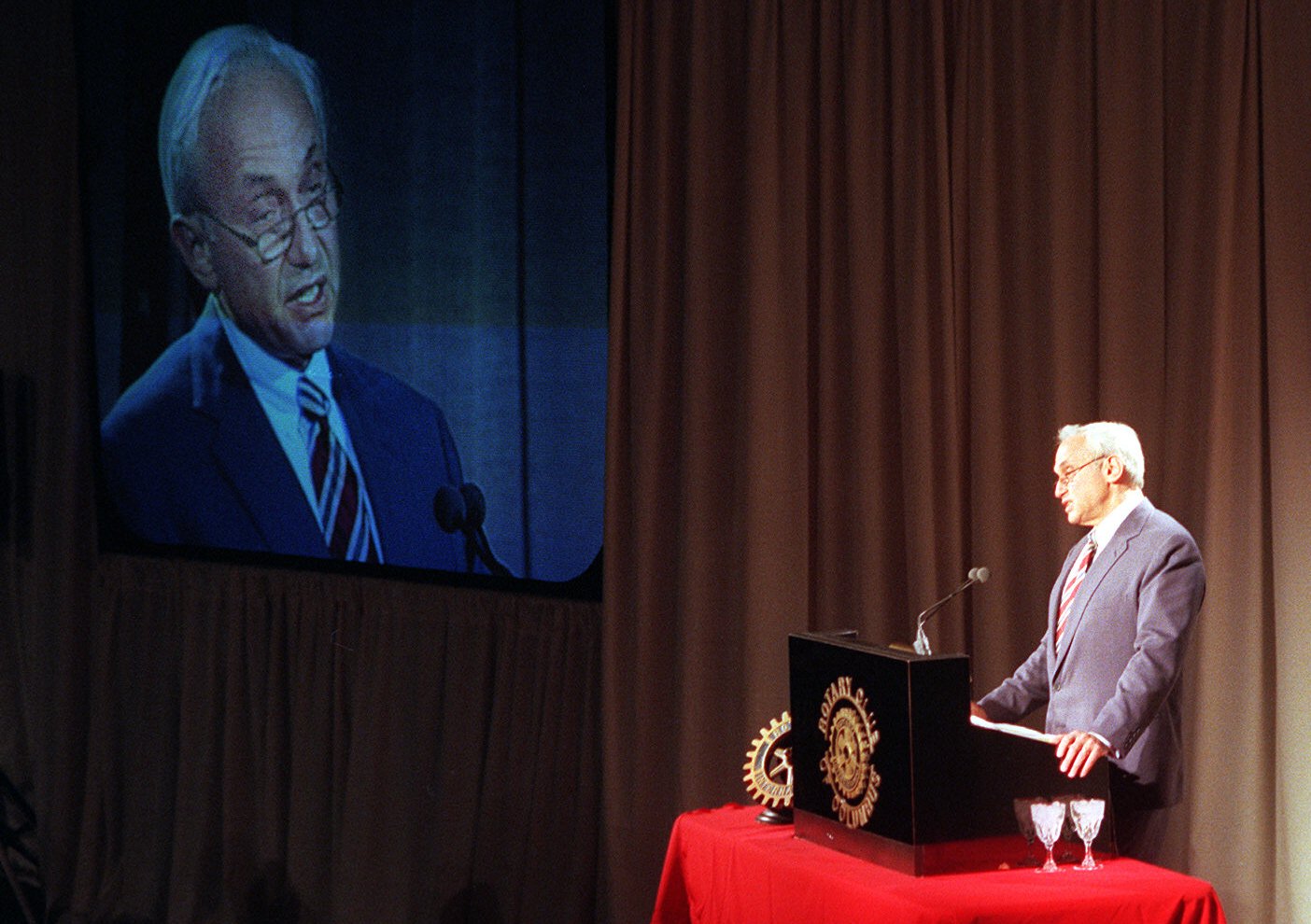

At a Rotary Club of Columbus meeting on Jan. 29, 1996, Wexner unveiled his next turn of the wheel.

He described a project with offices, residences and up to 4 million square feet of retail space all built around a town center. Easton, he said, would be "the most exciting and diverse retail space ever developed in the Midwest."

Wexner, Georgetown and Steiner, now a part of the team, came up with a design and started to sell it. Even though Easton hedged its bets by building a large enclosed mall space — Easton Station — in the center, reaction was still dubious.

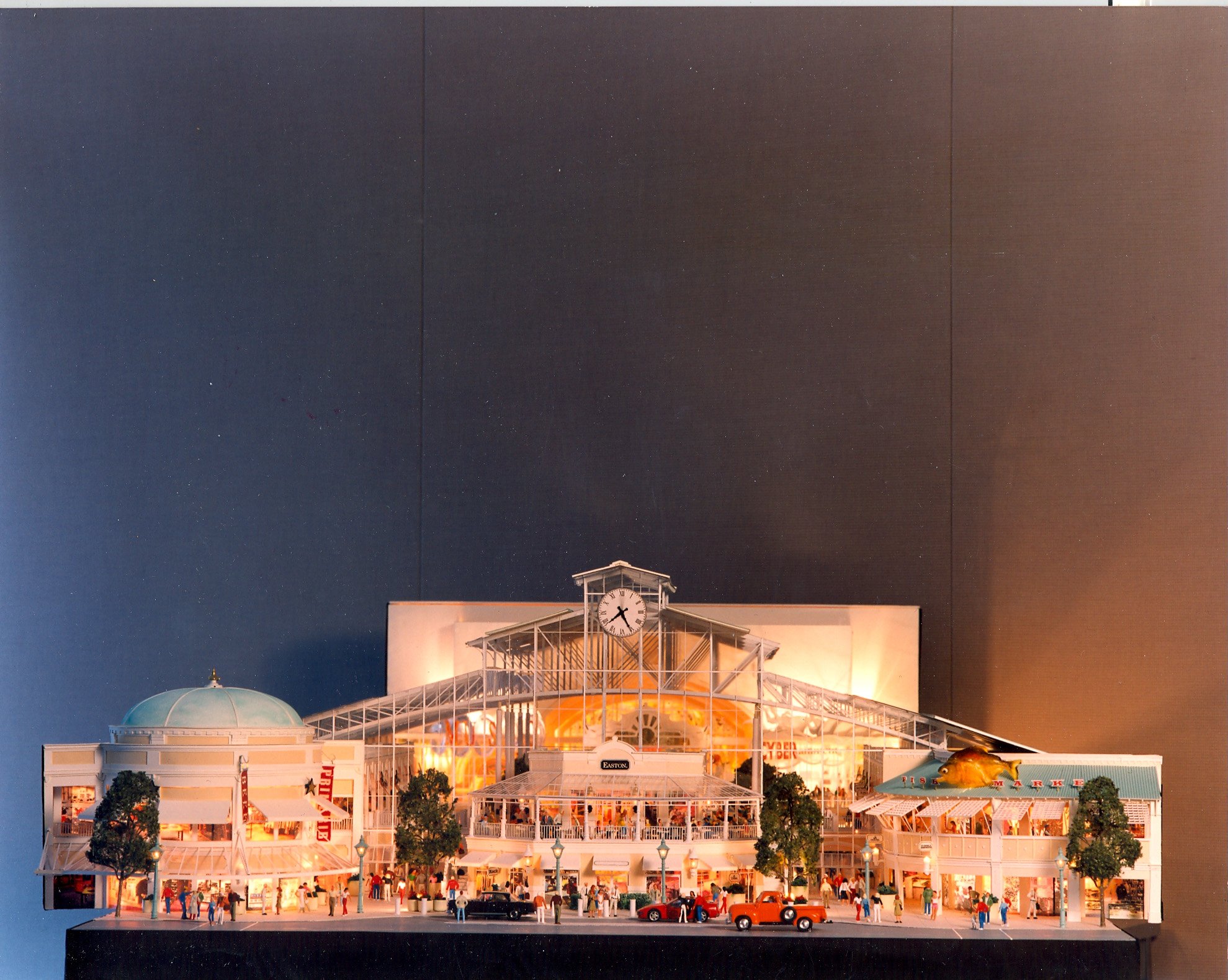

"I remember going to the annual shopping center convention in Las Vegas," Flatto said. "We had a big model of Easton we displayed. If you ever wanted to hear skepticism, you needed only to stand by that for an hour. People asked, 'Where is this?' We said, 'Columbus, Ohio.' Eyes would roll and people would say, 'This is crazy.' "

Wexner worried that he would have to fill Easton from his own staple of stores such as The Limited, Victoria's Secret, Abercrombie & Fitch, Lane Bryant, Justice and Bath & Body Works. He didn't have to worry long.

"When we planned the first phase, we thought we’d have to take half the retail spaces because none of our competitors would have faith in it. Instead, we got crowded out," he said. "The fact that developers didn’t see it but retailers did was really encouraging."

The design filled Easton's spots with a mix of mall mainstays and some premium tenants such as Restoration Hardware, the Cheesecake Factory and Virgin Megastore.

But Easton also dramatically changed the ingredients in the mall stew. Instead of anchoring the center with department stores and filling it with clothing retailers, Easton stocked the shelves with restaurants and entertainment destinations. Tenants included the Funny Bone Comedy Club, Shadowbox theater, a two-story Barnes & Noble bookstore and a 30-screen movie complex. A 300-room Hilton hotel showed that Easton was a place to hang out, not just a place to shop.

"We merchandised it differently, with entertainment and food in addition to traditional types of stores," Wexner said. "We thought food would be an important part of the shopping experience. ... Developers thought food would make people sit down and eat and get sleepy. I thought that was nonsense. We saw a mix of uses."

Easton added to the mix by booking concerts, entertainers and annual events such as the holiday tree-lighting, which attracts thousands.

"The fundamental thing is building that emotional connection," Steiner said. "If you go to Costco, it's a brain decision. There has to be an emotional connection here. We don't sell necessities. We sell experience."

The reality

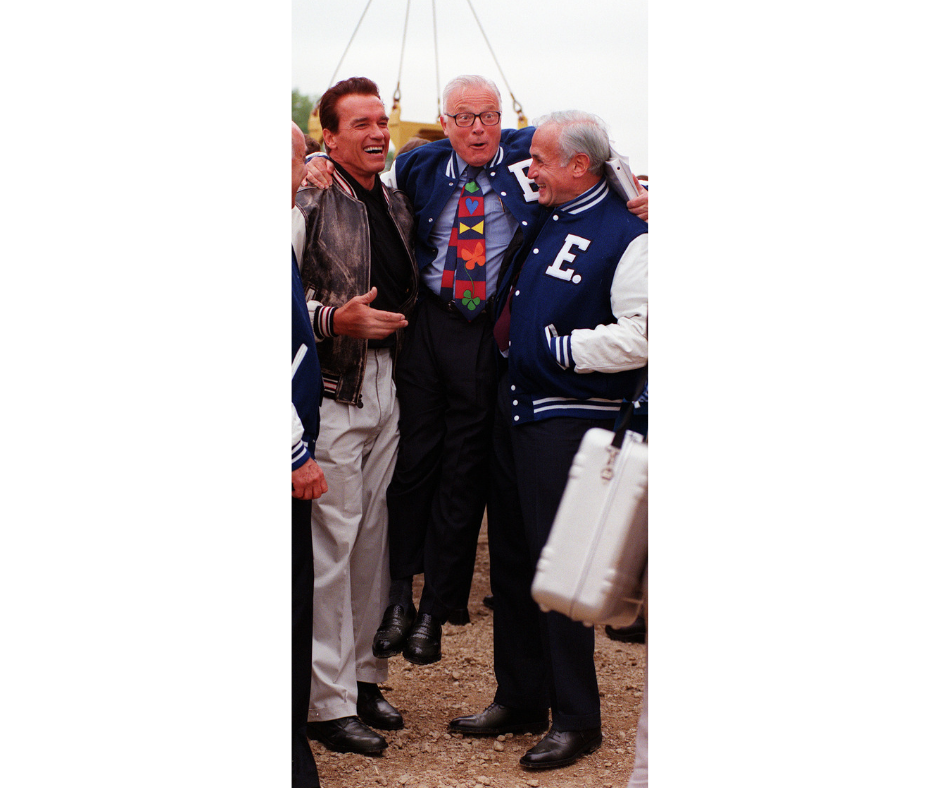

Easton's grand opening, featuring Arnold Schwarzenegger, Sylvester Stallone and other celebrities, illustrated that this would not be an ordinary shopping center. Wexner, Flatto and Steiner soon knew they had struck a chord.

"Michael Overton, at the Cheesecake Factory, said, 'I’ll know in the first two weeks if this works,' " Flatto recalled. "Two weeks later, he called up and said, 'You’ve got a winner.' It was quite apparent from the beginning that this was a format customers really yearned for."

In its first full year, Easton Town Center drew 12 million visitors and quickly became central Ohio's premier retail destination.

"Easton Town Center dispelled retail industry myths such as 'no one will walk outside in cold climates' and that mixing uses is too hard in suburban communities," said Charles Bohl, director of the Master in Real Estate Development + Urbanism Program at the University of Miami and the author of "Place Making: Developing Town Centers, Main Streets and Urban Villages."

"It also mixed a wide variety of retail formats together in one place, which broke the mold for discrete power center, shopping mall, lifestyle center formats."

Easton wasn't the first open-air lifestyle center, but it was one of the first in a northern climate. Since then, countless others have followed suit, including Steiner's own developments such as Bayshore outside Milwaukee, and Liberty Center outside Cincinnati.

"I was in Istanbul 10 years ago," Wexner said. "A colleague said, 'You have to see Istinye Park,' this shopping center. We drove to it and parked and I thought, 'This is terrific.' I was taking photos, I was inspired. Later, I was back in Istanbul and the developer and I met for a cup of coffee. He said, 'I’d like to thank you. We copied Easton.' They had copied our style. No wonder I liked it!"

Easton proved far more than a local shopping destination. With its blend of entertainment, restaurants and hotels, it has served as a get-away spot for guests far outside Columbus.

"Our trade area is 80 miles north-south and 40 miles east-west. That's just our core area," Steiner said. "We didn't realize it would have such a wide draw."

Though the center was widely considered a success, it wasn't without challenges. The biggest early failures were Planet Movies and Planet Hollywood, and the All-Star Cafe, which closed after less than two years. Another early casualty was the Virgin Megastore.

"The things that didn’t work out as well as we would have liked were some of the retail concepts that were larger — the big Virgin music concept, the initial movie theater, which was a joint venture with Planet Hollywood — that fell flat and required us to redo those," Flatto said. "But those were all fixable."

The early returns were positive enough for Easton to quickly move ahead on Phase II.

"We envisioned the second half being an enclosed mall," Flatto said. "We didn’t know how big this open-air concept could be. But the comments that kept coming back: The thing the consumers liked most was to window shop, to be outside."

A month after the second phase opened in September 2001, Easton received its first serious threat when Polaris Fashion Place opened 11 miles to the north. Polaris was a traditional mall with seven anchors and about 150 tenants.

Easton didn't end up a Polaris victim. Instead, the combination of Easton, Polaris and The Mall at Tuttle Crossing, which had opened in 1997, eventually crushed Columbus' first-generation of malls, Northland, Eastland and Westland, along with Downtown's Columbus City Center.

And though Easton's first phase was revolutionary, Easton's second phase raised the bar. Anchored by Nordstrom and Macy's, the second phase was wide open, built around a fountain and served by a grid of Main Street-style buildings.

In addition to Nordstrom, the second phase eventually included several retailers new to Ohio, including Smith & Wollensky, an Apple store (seventh in the nation) and Anthropologie. Those tenants were followed by other premium occupants — Tiffany & Co., Louis Vuitton, Burberry, Lacoste, Michael Kors, Filson, Shinola and American Girl.

Along the way, Easton proved a laboratory for emerging central Ohio businesses including Homage, Jeni's Splendid Ice Creams, Condado Taco, Red Giraffe and Hot Chicken Takeover.

New this year are central Ohio's first Shake Shack, Tory Burch and 7 for all Mankind locations. A phase now under construction will add more first-in-Ohio destinations such as True Food Kitchen, Forbidden Root and Ivan Kane's Forty Deuce.

"Easton is generally recognized as a top 30 or 40 retail project in the country," Flatto said. "In sales per square foot, total sales, visitation, it has had unequivocal success. Tenants want to be a part of that."

Easton's restaurant and retail sales have topped $1 billion — more, Steiner said, than Polaris and Tuttle Crossing combined.

But though the Town Center has been a financial success for retailers, Steiner and the others realize they might have missed an opportunity. They say they wish they had built more residential and offices in the town center area, instead of separating those uses from the the town center by major thoroughfares.

"I would have integrated residential much earlier," Steiner said. "I also would have included more green spaces and gone more vertical."

Flatto agreed. "If it were up to me back then, I would have pushed for higher levels of density throughout," he said.

Easton's next phase, with apartments and offices, will remedy that, they say.

The legacy

Wexner is proud of Easton's past and excited about its future.

"As I take those drives through Easton in the evenings and mornings, I’m reminded of when it was under construction. My oldest son, Harry, was just a few years old and we were driving around in a Jeep, through the mud and with the buildings going up. He was in a car seat in the back.

"We drove off the site and were driving home and he said, 'Daddy, who made that mess?' I said, 'I did.' He said, 'Does Mommy know?'

"But I’m very proud of what we’ve done. We haven’t made a mess and hopefully what we’ve done is insightful and will continue to be insightful for the next 20 years."