FROM JAIL TO HOMELESS

Corrections officials say lack of transitional housing endangers recovery process and costs taxpayers in the long run

Jessica Norton, director of inmate services at the Rockingham County jail, is frustrated with the lack of safe and affordable housing for people leaving incarceration. The county has an almost complete absence of residential addiction treatment options and transitional housing. Deb Cram | Seacoastonline

BRENTWOOD — Jessica Norton worried greatly about the likeliness of survival of one of her inmates — due to be released that evening.

Staffers at the Rockingham County jail had worked with him to create a detailed re-entry plan, his first few days of freedom fitted with an appointment at the methadone clinic, meetings with a mental health provider and new primary care doctor, and a probation check-in. But it was all at risk, Norton said, because he was still homeless.

His plan was to get a hotel room.

“If he doesn’t find somewhere to go tonight, he will not meet any of the initial things on (his plan),” she said. “This gentleman, I am fearful for.”

Norton, director of inmate services at the jail, sighed deeply and rolled her eyes. “And the cycle begins again.”

Housing is the key

It’s the position of Stephen Church, superintendent of the Rockingham County Department of Corrections, that “constituents in crisis need some sort of housing.”

If that infrastructure is not there on the outside, he said, then the jail is doing its work for nothing.

Rockingham County Jail Superintendent Stephen Church discusses the ramifications of the county not having adequate transitional or sober living options for his population. Deb Cram | Seacoastonline

“You work with these people starting day one when they come in, on social services, medical, mental health,” Church said. “Our mission really is, ‘What are we turning back into the community?’ It’s very easy to follow someone’s sentence and then say, ‘OK, get out.’“

But, he said, “these people are our citizens. It is our charge to address their issues. That is corrections 101.”

Jail is temporary, Norton reminds. “These people are going to relocate into your community.”

The first 24 hours after release from incarceration are the most lethal, corrections officials say. Many die of an overdose, or skip town and disappear. A select few remain on schedule with their reentry plan, and much of that has to do with attaining housing out of the gate.

“If they do not have a place to live, there’s no way the other things will fall into place,” Norton said. “If you do not have this basic need met of support, there’s no way you’ll attend appointments, that you’ll get your health insurance, that you’ll do anything, if you don’t know where you’re going to sleep at night, because your entire priority throughout the entire day will be finding where you’re gonna crash.”

Rockingham County lags

Despite being the second most populated county in New Hampshire, there is a scarcity in Rockingham County of residential addiction infrastructure — an absence of transitional, sober or supportive housing options. The void disproportionately impacts those incarcerated at the county jail in a largely rural area along North Road in Brentwood.

The agrarian area is dotted with farms, colonial homes, small ranch-style houses, a Baptist church and an RV campground. There’s no public transportation, let alone sidewalks.

Meanwhile, Rockingham County contains one of the main transportation arteries for drug trafficking in and out of the state, resulting in a barrage of out-of-state offenders finding themselves incarcerated at the Rockingham County jail. Last September, for example, the U.S. Attorney’s Office announced 40 arrests as a result of “Operation Devil’s Highway,” targeting drug distribution activity between Lawrence, Massachusetts, and destinations in New Hampshire.

For the most part, these drugs run through Rockingham County to reach any destination north. And if offenders are caught in Rockingham County, there’s a good chance probation will require them to stay in the county after their jail stint unless a transfer is approved.

In 2017, Rockingham and Strafford counties tied for the second highest suspected drug use resulting in overdose deaths per capita at 1.36 deaths per 10,000 population. Per state Department of Health and Human Services data, between June 2016 and July 2017, 16 communities in Rockingham County saw between one and four drug deaths, while two communities saw five to 10.

County commissioners have begun to have conversations about potential support of a correctional reentry initiative that would involve housing infrastructure, specifically a 90- to 120-day treatment program post-release part of a $44 million overall county facility plan. If commissioners decide to include the project in the upcoming budget, the county delegation of state representatives will vote on it in the coming months.

Church said the coronavirus pandemic has not changed the budgeting process, and commissioner meetings remain on track. Church noted shelters they would have previously used for released inmates as housing options are now restricting intakes because of COVID-19, leaving their hands tied even tighter.

The push for a county transitional housing project has come largely from the Department of Corrections itself, and Rockingham County Drug Court director Christine McKenna, all of whom consistently watch the revolving door at the jail, and field the phone calls about deaths.

Though the jail only has numbers for its facility, the recidivism rate for the 5,300 individuals it processed in 2019 was 57%.

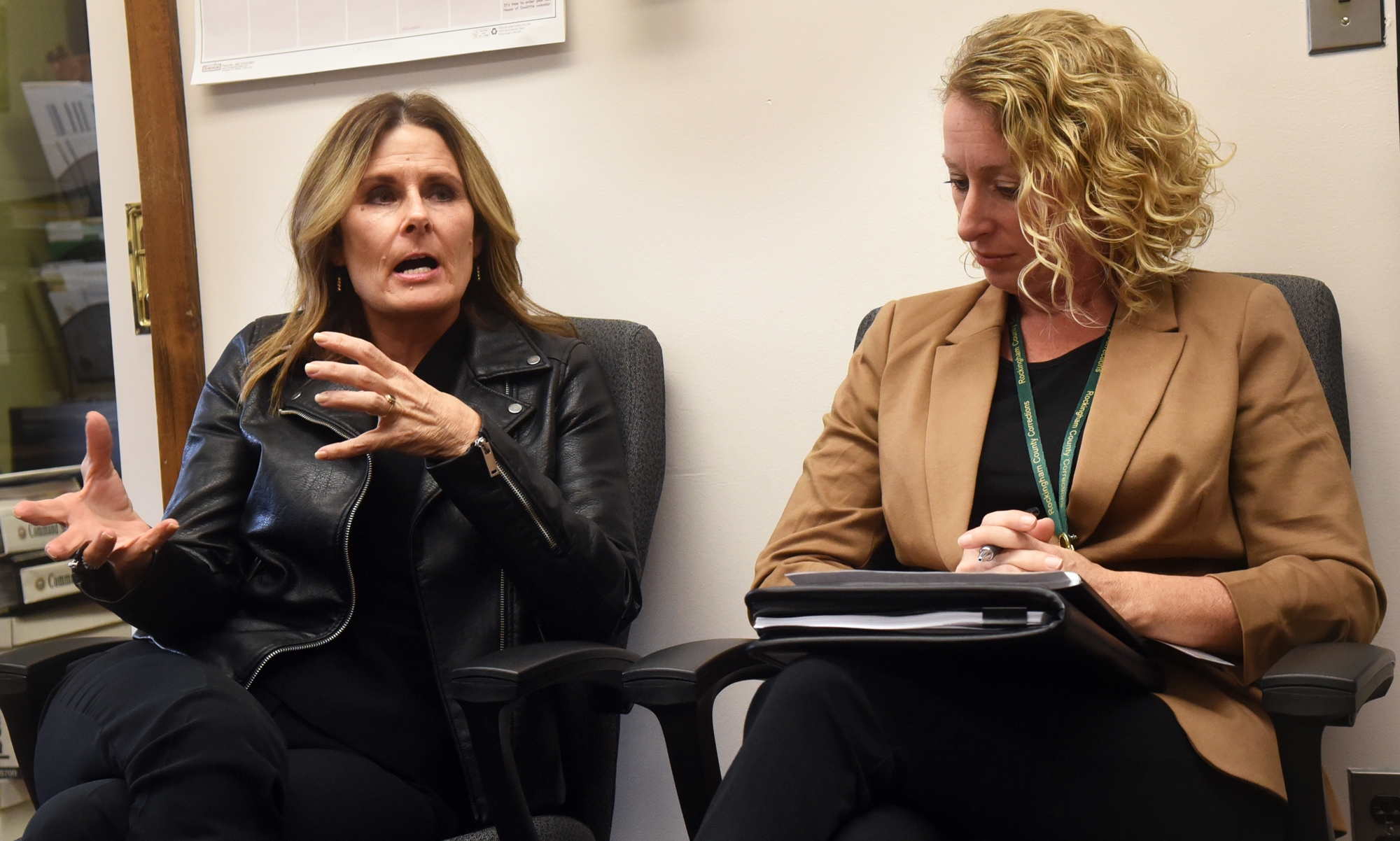

Rockingham Drug Court Director Christine McKenna, left, and Director of Inmate Services Jessica Norton are frustrated with lack of housing and transportation that could be key components for an inmate to become successful after release. Deb Cram | Seacoastonline

“My feeling is it’s a community’s responsibility to provide resources for all members of the community — the good, the bad and the ones who might be considered ugly, the ones we don’t necessarily want to think about,” McKenna said. “We’re still going to be in the same spot if we don’t help people get better, or get well.”

The gender-specific Granite House for Men in Derry, 45 minutes to an hour away from most locations in the Seacoast, and run by Granite Recovery Centers, is the only sober residential facility in the county, officials say.

The only homeless shelter accepting single men is Cross Roads House in Portsmouth, which has a year-round wait list.

Church said Rockingham County is in a “critical” situation when it comes to the absence of both housing and transportation for his population.

“I’m going to lose them within 24 hours if I don’t have both,” he said. “We have to remove those blocks and almost spoon feed them. That transition to the unknown, exposure to many giant roadblocks. If we can get them through that first 24 hours, we have a must better chance of them continuing on.“

McKenna, though always attuned to the lack of addiction infrastructure, began ringing the alarm when she had two women who were good candidates for Rockingham County Drug Court, but because they could not find a place to live in the county, they were almost ineligible for the program.

Studies have shown drug courts reduce recidivism rates by approximately 40%, and can save counties millions of dollars by keeping people out of jails, per county reports.

“When you’re left with, ‘Oh my god, we have this phenomenal program that has treatment and resources available, and then we might have to have someone leave because they don’t have housing?'” said McKenna, who was formerly chief of the Rockingham County Probation/Parole Office in Exeter.

“I was beside myself. I’m thinking the lunacy of it. And frankly, I was just angry that this is where we are.”

McKenna feels Rockingham County continues to be overlooked when state and federal funds are being allocated for the opioid crisis, and she’s not sure why — the biggest example being the absence of a “Doorway” hub, while nearly every other county received a location.

Both McKenna and Church understand the barriers to establishing housing for drug addicted and formerly incarcerated populations. There’s little incentive for a private entity to start a project as such, because many clients are homeless with little to no means, and Medicaid does not pay for rent or room and board. There’s also the argument about public funding for these services, and what people want their tax dollars going to.

“We tell people, ‘You should get a job, you should go to treatment.’ Why are we making this harder?” McKenna said. “Everyone will benefit from having a healthier community, and healthy means body, mind and soul. I think we can all agree on that. There’s always going to be a cost. Where do you want to pay it, on the front end or the back end?”

Norton added, “It’s not about what’s right, wrong or political. It’s are you a human being?”

Examining the costs

Numbers from the New Hampshire Department of Corrections, which operates the state’s prisons and three transitional housing facilities, show costs for putting someone up in transitional housing is much less than them ending up behind bars again.

In 2016, the average annual cost to house an offender in transitional housing was $17,586, while housing an offender in prison cost $35,832. The daily rate breaks down to $48.13 for transitional housing, and $98.17 for prison.

The Rockingham County jail is located on North Road in Brentwood, a rural area. Deb Cram | Seacoastonline

That same year, transitional housing made up a mere 5% of the state DOC’s operating budget at $5 million, while prisons made up 77%, at more than $83 million.

Church said the Rockingham County commissioners have been “extremely involved and supportive” of correctional reentry initiatives, but it’s a question of how that gap will be filled.

Currently, they’re looking at county funding, finding funding elsewhere or “working with anybody we can to provide housing,” Church said.

In March, U.S. Attorney of New Hampshire Scott Murray announced nearly $60 million in Department of Justice grants available to help communities address public safety by supporting successful reentry of offenders into their communities.

“When prisoners are released from custody, we need to make sure that they can transition effectively back into society,” Murray said in a statement. “By assisting these individuals to become productive members of society, we reduce the risk of recidivism and improve public safety. These grants can assist our communities in accomplishing these important goals.”

Some of the grants, like the Second Chance Act Community-based Reentry Program, for example, can be used for both substance abuse treatment and comprehensive housing.

In Rockingham County, it currently costs $97.50 a day to house an inmate at the county jail, which sees a consistent year-round population of approximately 140 men. And while the jail processed more than 5,000 people last year, there’s no way to account for how long each person stayed, as some are immediately transferred or bailed out, while others serve typically 12 months or less at a time.

“Jail doesn’t vaporize people,” McKenna said. “They’re coming out to pour your coffee at Dunkin’ Donuts, change your oil in your cars, all types of services.”

Church, a staunch conservative, went as far as saying the absence of housing opportunities for these individuals is creating more victims on the outside, because it increases recidivism rates.

Eric Spofford, founder of Granite Recovery Centers, which operates the Granite House for Men in Derry, does not see the sober home landscape as operating within county lines. If someone wants help, the services are here in New Hampshire, he feels.

“We’ve certainly made significant progress,” Spofford said. “When I opened up our first sober living in 2008, it at the time was the only one in the state, starting with 11 beds for men. I understand where Rockingham County folks would be concerned with the county, but the way I see it operate day-to-day isn’t really confined by the county lines.”

Spofford said sober and transitional home models are meant for populated areas close to jobs and recovery meetings, pointing to why Manchester and Nashua have become a “hot bed” for a significant number of programs.

“Most of Rockingham County is remote,” he said. “Portsmouth is the most populated area and real estate is incredibly expensive. Outside of that, where can you put a sober living facility where folks can walk to employment and be self-supporting?”

Spofford said Granite Recovery Centers, which operates residential and treatment facilities around the state, receives approximately 500 phone calls per month from individuals looking for in-patient levels of care. He sees the bottleneck in the state being specific to individuals with Medicaid insurance seeking residential substance abuse treatment — many incarcerated individuals would fall into this category upon release.