Artist rendering of how the finished MAPS projects would look in the overall city-scape upon completion. Concept was done in 1992 by the architectural firm of Frankfurt-Short-Bruza. [Courtesy of The Oklahoman Archives] |

Civic reinvention constant with MAPS initiatives

MAPS 4 follows a long history of changes within Oklahoma City, all with roots tracing back to the original MAPS projects.

Many civic leaders are quite capable of dreaming up fantastic reinventions of their cities — but Oklahoma City’s transformation is far from routine.

MAPS – the word coined for Metropolitan Area Projects – has had its ups and downs over the years, becoming a brand for tackling big dreams with a limited one-cent tax.

And that brand has expanded from fixing downtown, the Oklahoma River and the Fairgrounds to rebuilding schools, building miles of trails and sidewalks, senior wellness centers, a streetcar system, convention center and massive new city park.

But as residents decide on Dec. 10 whether to approve a fourth MAPS, the history of the initiatives provide a picture of a city that overcame mistakes, dealt with setbacks, and has become a model for other communities across the country.

The Oklahoma River was still little more than a drainage channel when trails and a park pavilion were built just west of the Lincoln Avenue bridge over what was then known as the North Canadian River. This would soon become the start of the Boathouse District. [Courtesy of The Oklahoman Archives] |

An entire generation has no memory of an Oklahoma City that was literally dying before the passage of the first MAPS. The city’s best and brightest were moving elsewhere, the economy was in shambles, and a downtown had been torn up by an aggressive Urban Renewal program but not totally rebuilt.

An economic bust triggered by a collapse in oil and gas, real estate and banking overwhelmed the city and left its urban core a ghost of the vibrant destination remembered by old-timers.

“Downtown is dead,” the late Councilman I.G. Purser stated back in 1988. “And we helped kill it.”

Indeed, the whole city was in a death spiral. Ron Norick, elected mayor in 1988, joined the Greater Oklahoma City Chamber in aggressively trying to revive the city’s fortunes. They did what many cities were doing – asking residents to pass tax incentives to attract new employers.

But a series of economic development incentives involving tax increases approved by voters had failed to lure a single job to Oklahoma City.

Norick thought the city had an excellent shot at winning a 4,500-job airline maintenance plant when it offered up an incentives package to United Airlines in 1991. The city lost the race to Indianapolis, which didn’t offer up as many incentives, but did have something else — quality of life.

Norick strolled through downtown Indianapolis and saw a lively downtown, home to major-league sports, shopping, hotels, entertainment and a growing residential population.

Bricktown was a relatively limited destination with about a dozen restaurants and bars as shown in the 1996 photo before construction of the Bricktown Canal and Chickasaw Bricktown Ballpark as part of the original MAPS. The cleared block for the ballpark can be seen in the top center of this photo with California Avenue, the future canal, dead-ended on the west edge of the ballpark site. [Photo by The Oklahoman Archives] |

Downtown Oklahoma City, meanwhile, offered nothing in terms of entertainment and plenty of empty office space. Bricktown was attempting to emerge from bankruptcy as a warehouse entertainment district, but in the early 1990s was home to only a handful of restaurants.

Downtown’s only hotel, meanwhile, was on the verge of losing its Sheraton franchise, and the sole historic hotel, the Skirvin, had sat dark and empty since 1988.

The Oklahoma River was often a dry drainage ditch and the area south of Reno Avenue was blighted prior to a transformation that started with the original MAPS and continued with MAPS 3. [The Oklahoman Archives] |

Downtown and the river weren’t the only parts of the city needing an infusion of resources, vision and new direction. Norick saw a convention center that was never suitable for drawing conferences, but instead was a 1971 arena surrounded by small, outdated meeting rooms decorated with wood paneling and shag carpeting.

The owner of the city’s minor league baseball team was seeking to sell the organization even if it meant moving to another city. The city had been informed that All Sports Stadium at the Fairgrounds didn’t meet league standards and had to either undergo an extensive upgrade or be rebuilt.

The State Fair board, meanwhile, were not as worried about the ballpark as they were about losing its national equine events due to aging buildings and infrastructure.

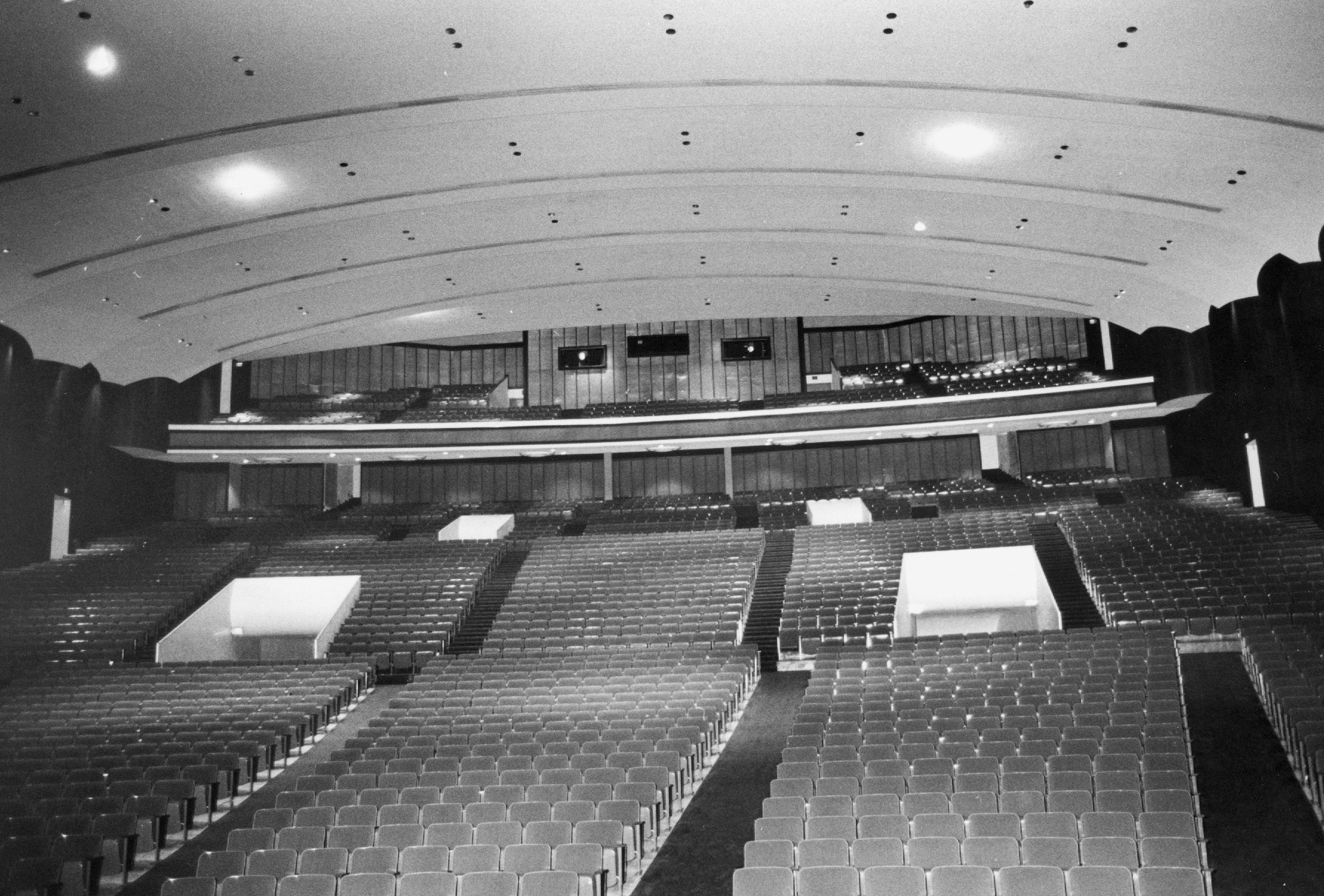

he Civic Center Music Hall was deemed a poor host for concerts and performances as shown in this 1980 photo taken before it was gutted and transformed into a modern performing arts hall as part of the original MAPS. [The Oklahoman Archives] |

The Civic Center Music Hall was shabby and worn down. The downtown library had seen better days. Nothing was up to par.

Walking through Indianapolis, Norick realized just how bad things were back in downtown Oklahoma City. The heart of the city was in bad shape.

The original Metropolitan Area Projects are shown in this rendering published on the 10th anniversary of the program. [The Oklahoman Archives] |

Norick and the chamber, then led by veteran ad man Ray Ackerman, teamed up and looked at the city’s biggest challenges and opportunities. They put together a ballot and campaign that gave voters a choice – support a five-year, one-cent sales tax that would fund nine different projects.

Voters could approve all, or reject all. At one point during the lead up to the campaign, the chamber delivered discouraging polling to Norick and suggested the campaign be put on hold. Norick refused and threatened to quit as mayor.

The gamble paid off. On Dec. 14, 1993, voters committed to building a new downtown ballpark, an arena, a downtown library and a Bricktown Canal.

Drone image of Boathouse District and Oklahoma River. [Image by Dave Morris/The Oklahoman] |

They agreed to fund a decades-long dream of restoring what was then known as the North Canadian River — a virtual drainage ditch — back into a waterway that would once again be a source of civic pride. They agreed to fund long-needed makeovers of the convention center, the Civic Center Music Hall and Fairgrounds.

They dared to hope that by voting $3 million for a passenger rail operation, that matching federal funds could be secured to make that dream come true, as well.

Rumble the Bison carries a Thunder flag before game Game 6 of the Western Conference finals in the NBA playoffs between the Oklahoma City Thunder and the Golden State Warriors at Chesapeake Energy Arena in Oklahoma City, Saturday, May 28, 2016. [Photo by Bryan Terry/ The Oklahoman] |

The MAPS story isn’t without its share of drama, disappointment and setbacks.

The dream of a passenger rail system died in a political showdown that displayed how one congressman’s opposition can drown out the support of fellow representatives and senators, as well as a popular mayor. Cost overruns and project delays drew serious criticism and debate. Designs and assumptions changed, but often for the better.

And as Norick prepared to end his time as City Hall, budgeting problems still plagued the MAPS program and a majority of the city council leaned toward shelving the arena.

Each succeeding mayor built on Norick’s gamble. Kirk Humphreys, elected in 1998, convinced voters to “fix MAPS right” by extending the sales tax for six months. The arena was built and all of the projects were finished as promised.

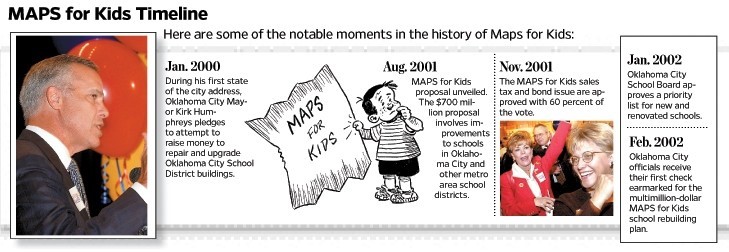

Humphreys then teamed up with educational leaders to launch the $700 million MAPS for Kids, also approved by voters, which rebuilt every public school, many of them in dreadful condition, throughout the city. This time, the budget and timing went as planned, lessons clearly learned at City Hall during the first MAPS.

Mayor Mick Cornett with former mayors Ron Norick and Kirk Humphreys unveiling a rendering of the 2013 Oklahoma City Christmas ornament celebrating the MAPS program on display at BC Clark Jewelers in downtown Oklahoma City Friday, Nov. 1, 2013. [File photo by Paul B. Southerland/The Oklahoman Archives] |

Mick Cornett, elected as mayor in 2005, built on the legacy of Norick and Humphreys by first showing just how right Humphreys was in urging the city to extend the MAPS tax and build the arena. Without the arena, Cornett could not have convinced the NBA to temporarily relocate the New Orleans Hornets, displaced by Hurricane Katrina, to Oklahoma City.

That stint, in turn, led to the NBA approving a move of the Seattle SuperSonics to Oklahoma City where the team was transformed into the Thunder. A temporary tax, not part of the MAPS initiatives, brought the arena up to NBA standards and built the team a practice arena.

The Oklahoma River Trail that is part of the Maps3 project on display during The Oklahoma City Community Foundation’s 50th anniversary ceremony with a Oklahoma River Trail dedication along the north shore in Oklahoma City, Okla. on Tuesday, May 14, 2019. Civic leaders, runners, cyclists and walkers gathered to dedicate the Oklahoma City Community Foundation River Trail that was highlighted with 800 trees, stone park benches and wildflower growing areas. [Chris Landsberger/The Oklahoman] |

Cornett then led the passage of MAPS 3, which was split between further improvements to the urban core while also addressing neighborhood needs throughout the city.

On Dec. 8, 2009, voters approved a MAPS 3 tax that would pay for a new convention center, downtown park and streetcar system, new barns and exhibit halls at the Fairgrounds, senior wellness centers, a white water rapids venue and other additions to the river, and miles of trails and sidewalks citywide.

The $777 million MAPS 3 is still a work in progress with most of the projects set for completion over the next two years.

When the MAPS 3 tax expired, Cornett and the council asked voters to approve a temporary, non-MAPS extension, Better Streets/Safer City, that included 13 bond propositions totaling $967 million for rebuilding streets, police and fire facilities, and a 27-month continuation of the expired MAPS 3 penny sales tax that was forecast to generate $240 million for street resurfacing, streetscapes, trails, sidewalks and bicycle infrastructure.

In all of the votes leading up to the Better Streets/Safer City, the bond and sales tax rates had stayed at historic levels. But at the urging of public safety unions and supporters, the Better Streets/Safer City ballot also included a permanent ¼-cent sales tax increase to hire 129 more police officers and 57 more firefighters with an annual $26 million boost for public safety and other day-to-day operations.

Voters again passed the entire ballot.

MAPS 4 is the most ambitious effort to date and represents a generational change at City Hall where four of the nine members of the city council, including Mayor David Holt, are age 40 or younger. Dubbed the “MAPS generation,” they represent a shift in focus where social issues and neighborhood needs take priority over traditional capital improvement projects that have dominated past MAPS efforts.

Oklahoma City Mayor David Holt speaks during the state of homelessness address at the Tower Theater hosted by the Homeless Alliance, Tuesday, June 4, 2019. [Doug Hoke/The Oklahoman] |

Some of the 16 projects are representative of traditional MAPS projects, including $115 million for upgrades to the Chesapeake Energy Arena and the Thunder practice arena (both approaching 20 years of age), $37 million for a multi-purpose stadium, $30 million for more senior wellness centers, $38 million for a new animal shelter and $63 million for a fairgrounds coliseum.

But more than half of the funding will go to addressing social issues including youth centers and programs, mental health and addiction, a family justice center, beautification, a diversion hub, housing and programs for the homeless, transit and parks.

If passed, it’s the sort of initiative that will once again be historic and continue a civic transformation born a quarter century out of pure desperation.

What will you pay?

The Oklahoman’s MAPS 4 cost calculator can help you estimate how much of your sales tax would be allocated to MAPS 4 if the project is approved. Enter in an estimated monthly amount spent on items subject to sales tax — things like groceries, clothes, home supplies, decorations or other tangible products — to see how much MAPS 4 could cost you over the next 8 years.