Big break turns to big fight

DNA discovery in yogurt shop murders sparks FBI standoff

In the spring of 2017, veteran Travis County prosecutor Efrain De La Fuente called Bob Ayers, the father of one of four girls brutally murdered at an Austin yogurt shop in 1991. He had exciting new information to share, a DNA discovery that he hoped could bring resolution to the nearly 30-year-old case.

After years of roadblocks, setbacks and dead ends, investigators finally had identified forensic evidence that might lead to the girls’ killer.

De La Fuente explained that an Austin police cold case detective had submitted a new kind of DNA profile called Y-STR into a searchable database. Although there was no name attached, the match could identify a possible killer’s male relatives and help police track down the perpetrator.

“It was a great day. We thought this was really going to break our case, and they were elated as well,” De La Fuente recalled.

Elation quickly turned to disappointment and, then, outrage.

READ: Yogurt shop controversy: Debate focuses on the use of family DNA to solve crimes

The discovery they hoped could finally lead the investigation to closure instead triggered a nearly three-year standoff between local prosecutors and the FBI, a fight stretching from Austin to the U.S. Capitol.

It has led to arguments about the interpretation of federal law and privacy protections and to scientific debates about the significance of the new type of DNA that investigators want to use. The controversy, which investigators recently revealed to the American-Statesman, has ensnared U.S. lawmakers and prompted the possibility of legal action by one law enforcement agency against another.

“I thought this was going to be the beginning of the big break that would help us,” said Ayers. “Instead, we’ve been slapped in the face by the FBI.”

In 2017, officials created a new team of investigators and prosecutors to review years of evidence in Austin’s infamous yogurt shop murders to determine whether to bring charges against any suspect or suspects. [Ricardo B. Brazziell]

Convictions upended and mystery DNA

De La Fuente could feel the years of heartache in the eyes of the parents who stood expectantly, reluctantly, skeptically across from him in a pale Travis County conference room in early 2017.

De La Fuente, who has worked on the case longer than any other prosecutor, listened as newly elected Travis County District Attorney Margaret Moore promised to take a new deep dive into the 26-year-old unsolved murders of four teenage girls at an Austin yogurt shop.

“I always felt I’m going to stay on the case, no matter where this journey leads us,” said De La Fuente. “I felt like they are owed that and a whole lot more.”

For De La Fuente, the yogurt shop case highlights how the justice system can rob families of resolutions they desperately need to move forward.

“People talk about our justice system and how it fails, and this is a prime case about how things that could go wrong did go wrong,” he said.

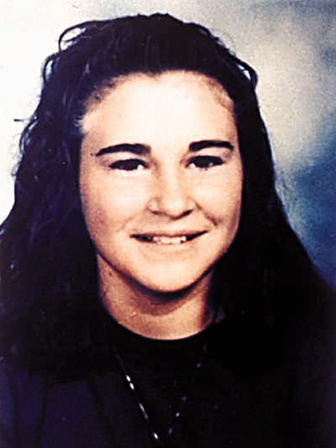

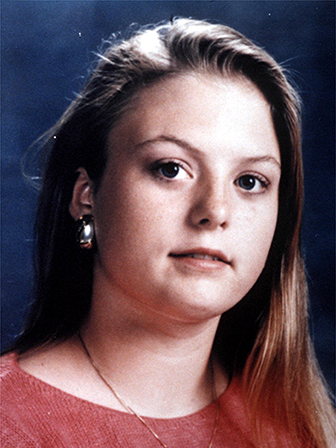

Jennifer Harbison and Eliza Thomas were working at the I Can’t Believe It’s Yogurt store off Anderson Lane on Dec. 6, 1991. Jennifer’s sister, Sarah, had been shopping nearby with Amy Ayers and came to the store to get a ride home. They were last seen alive shortly before the store closed at 11 p.m.

The four girls were shot in the head, gagged with their own clothes, and the building, along with much of the crime scene evidence, was torched.

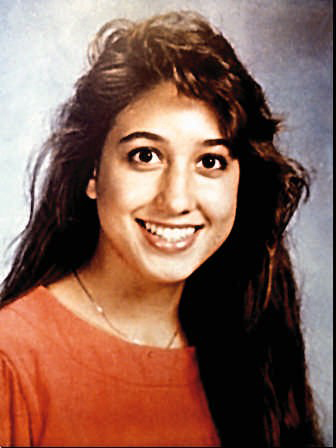

Amy Ayers

Jennifer Harbison

Sarah Harbison

Eliza Thomas

The crime stunned and horrified Central Texas. And the investigation that followed was as high profile as it was bungled.

In 1999, eight years after the crime, police arrested Robert Burns Springsteen, Michael James Scott, Maurice Pierce and Forrest Welborn and charged each with capital murder. In interviews with police, Springsteen and Scott confessed and gave statements that investigators say demonstrated they had detailed knowledge of the crime scene. They also made statements that put Pierce and Welborn there. The girls’ families began what they thought was a path to justice.

A Travis County grand jury declined to indict Welborn. But the cases against Springsteen and Scott crept forward to trial while Pierce remained in jail.

De La Fuente joined the prosecution team in 2000.

“When they pitched it to me, they allowed me to look at some of the evidence, and when I looked at some of those crime scene photos, it was just too much,” he said. “If ever there was a time to step up for a case, that would be the day — the way they came to die, their ages, the families not knowing for so many years.”

Robert Springsteen

Michael Scott

Forrest Welborn

Maurice Pierce

Prosecutors relied heavily upon the statements Springsteen and Scott made to police and used each‘s alleged confessions to help convict the other.

“I remember being in a conference room with the families, and they were just overwhelmed that the jury had convicted,” De La Fuente said. “It was a good day.”

Springsteen was sentenced to death; Scott received life in prison.

But over the next five years — just as victims’ families, law enforcement and the entire community began putting the case behind them — setbacks began rolling in.

Prosecutors decided that they did not have ample evidence to pursue a case against Pierce and dropped the charges against him in 2003.

Most wrenching, in 2006 and 2007, courts overturned guilty verdicts for Springsteen and Scott after the U.S. Supreme Court ruled in a separate case that two men’s statements could not be used against each other because it violated their constitutional rights to confront accusers.

Their cases were sent back to Travis County prosecutors to decide whether to retry the men.

That year, De La Fuente and other prosecutors learned about new science that could extract male-only DNA called Y-STR from a forensic sample. Investigators had DNA samples from the girls’ bodies, but until then, science wasn’t advanced enough to cull out male-only DNA from those samples. Officials hoped the Y-STR could at least narrow the field of suspects down to a family of men, even if it couldn’t provide the culprit’s identity.

A three dimensional model of the Yogurt Shop Murder is one of several pieces collected over the years investigating the cities infamous homicides. [Rodolfo Gonzalez/American-Statesman]

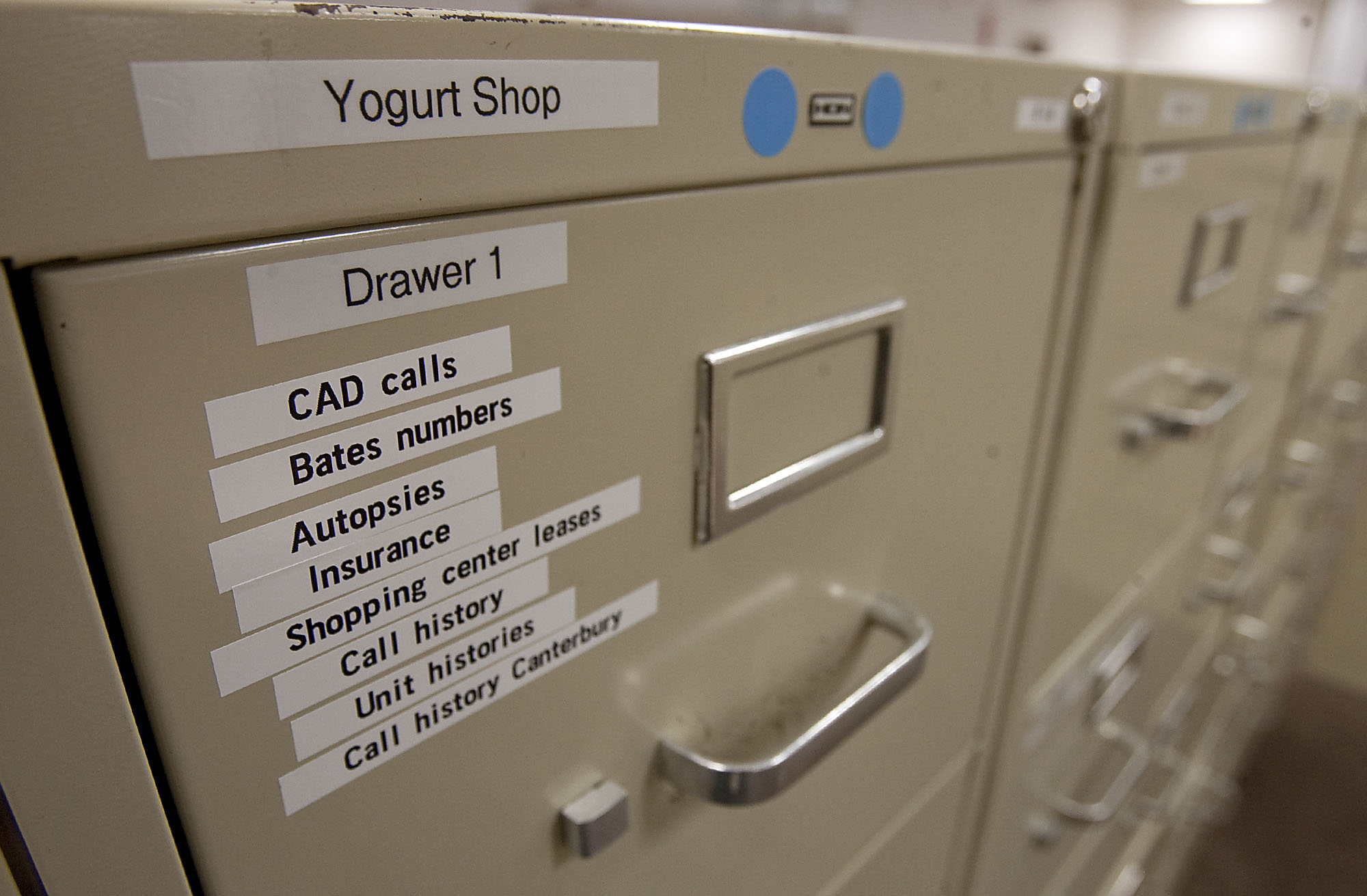

Filling cabinets at the Austin Police Department’s Homicide Cold Case Unit are still filled with documents and information on the Yogurt Shop Murders. [Rodolfo Gonzalez/American-Statesman]

In March 2008, a private lab in Virginia sent investigators the profile that they gleaned from a sample from Ayers’ body.

But the profile did not match Springsteen, Scott, Pierce or Welborn, and the Y-STR sample didn’t point to their families, either.

De La Fuente and other prosecutors dropped the cases against the men and decided not to retry Springsteen and Scott.

Eighteen years after their daughters’ deaths, investigators and the girls’ parents were back to square one, with scant evidence except a DNA profile belonging to a mystery person.

De La Fuente and the investigative team got back to work: “We went on a hunt to put a face to that profile,” he said.

Prosecutors don’t know whether the DNA belongs to the killer, but they believe it might belong to someone who could provide more details about what happened that terrible night.

They accounted for many of the customers at the shop that evening and got DNA samples from them. There was no match. They used yearbooks from the girls’ schools to build lists of their classmates, and then covertly gathered DNA samples from many of them off discarded soda cans or cigarette butts. Again, there was no match. Worried that first responders might have contaminated the scene, they tested every man who had gone into the burned-out yogurt shop. Still, no match.

“It was intense, very laborious,” De La Fuente said. “And very costly, too. But we were just hoping for information that could get us back into the courtroom.”

A match and a fight

Not long after prosecutors, cold case investigators and the new district attorney met with the families of the yogurt shop victims in 2017, Austin police detective Jay Swann learned about an array of online databases containing DNA profiles.

It was intriguing, because it held the profiles of male-only Y-STR samples like the one investigators had identified in the yogurt shop case. The National Center for Forensic Science at the University of Central Florida operates the U.S. Y-STR Database containing 29,000 samples for population research. Its website says it has samples from “government, commercial and academic resources throughout the United States” and that “all forensic laboratories and institutions are invited to contribute.”

Today, the website contains a disclaimer, saying that it does not function as a law enforcement database and “cannot be used to identify a particular individual whose sample is in the database. All donors are anonymous (and samples) cannot be traced back to specific individuals.”

Swann, praying the database would generate a fresh lead, entered the profile that had been developed by the private Virginia lab a decade earlier into the search engine. He got a hit.

De La Fuente remembers the phone call from Swann, and the flurry of activity that ensued.

De La Fuente and First Assistant District Attorney Mindy Montford sent a grand jury subpoena to the University of Central Florida on March 9, 2017, for information about who had uploaded the matching profile. Days later, they learned the sample had been submitted by a forensic analyst at the FBI.

“We have not lost hope,” says Efain De La Fuente, who has worked on the 1991 yogurt shop murders case longer than any other prosecutor. [Ricardro B. Brazziell/American-Statesman]

“We thought, ‘We are gold now,’” De La Fuente said. “They are going to bend over backwards for us.”

The investigative team arranged a conference call with the FBI.

Their hopes for a clear path forward quickly faded. The FBI had no intention of disclosing the information.

Montford said agency officials cited a 1994 federal law that created a national forensics database that law enforcement officials use for investigations. That law, they said, required officials to protect the identity of anonymous donors whose DNA was submitted to the Florida database for population research.

“They basically say, ‘We would love to help you, but we have a federal statute that says we can’t release it,’” Montford said.

She was dumbfounded. Prosecutors argued that based on their reading of the federal law, the FBI was allowed to release records about where, how and from whom they obtained the sample. But that argument fell flat.

FBI scientists explained that, unlike traditional DNA that confirms a person’s identity, thousands of men could have the same male profile as the one Swann found. Officials told the team that it would be nearly impossible to use the information to identify a single individual — a proverbial needle in a haystack.

The team kept pressing. They told the FBI that they realized that they might have to work from a large pool of people, but that the lead was the most significant they had gotten in a decade or more.

A team of prosecutors traveled to Washington, D.C., to meet with U.S. Rep. Michael McCaul, R-Austin, who was chairman of the House’s Homeland Security Committee, which oversees the FBI. They hoped that McCaul would help them navigate FBI bureaucracy and, if necessary, carry legislation if the law needed to be changed.

Last week, U.S. Rep. Michael McCaul sent a letter to the FBI asking them to do what they legally can to assist Travis County prosecutors and Austin police detectives in the yogurt shop murder case.

In a letter last week to an assistant FBI director overseeing laboratory operations, McCaul called upon the bureau to immediately provide as much information to Austin investigators as it legally can.

“As a Member of Congress, a former federal prosecutor, a concerned member of the Austin community, and a father of teenage daughters, I urge the Bureau to work with the State to provide this important information to authorities in Texas as soon as possible, as they work to secure long overdue justice for Amy, Eliza, Jennifer, Sarah and their families,” he wrote.

So far, the FBI has not budged.

At their wits’ end, De La Fuente and other prosecutors began considering a subpoena for the information. They say they are still weighing such an unprecedented step, but fear the litigation would cost untold time and money.

In a statement to the Statesman, the bureau said, “The FBI did not perform forensic testing in this case and cannot speak to this case.”

The FBI acknowledged that it had provided anonymous male profiles to the Florida university for a study into how many of those profiles exist in a specific population and were legally allowed to do so. But the bureau said, “These profiles are not suitable for matching to an individual.”

In their attempts to use the information, Travis County prosecutors are entering a national debate among law enforcement, scientific and judicial experts about the growing use of family DNA to try to solve investigations.

Some agree that the FBI is following the law by withholding the information that could place innocent men under suspicion. Others say investigators are rightly trying to use the latest science to solve a heinous crime.

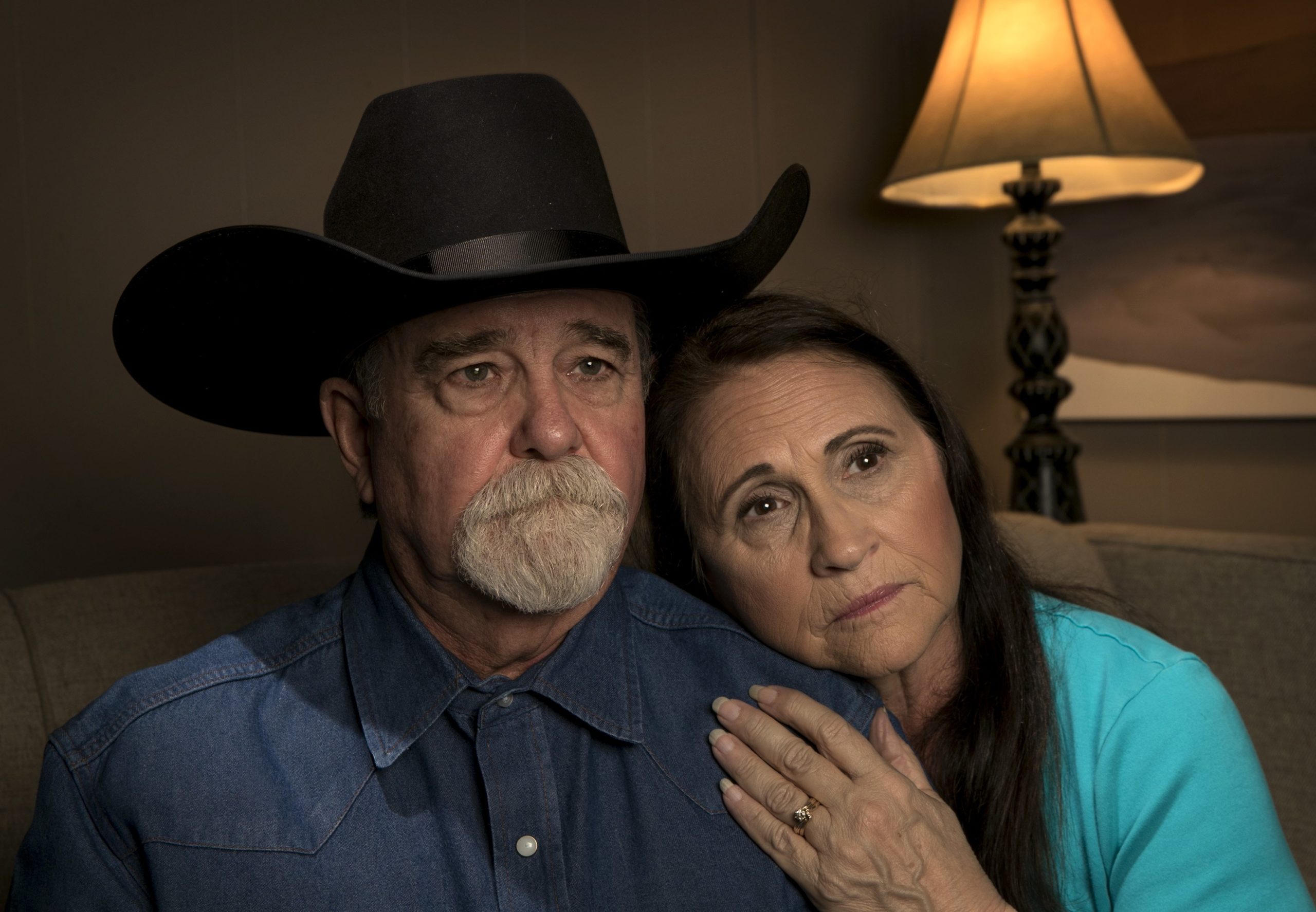

For Bob Ayers and his wife, Pam, the current problems with the yogurt shop murders investigation is just the latest in a nearly 30-year-long series of heartaches. “Every time we make a little headway, we take steps backwards,” Pam Ayers says. [Jay Janner/American-Statesman]

‘Hope is dimming’

For Bob Ayers and his wife, Pam, this roadblock is just the latest in a nearly 30-year-long series of heartaches.

“Every time we make a little headway, we take steps backwards,” Pam said. “My hope is dimming, considerably, unfortunately.”

Angie Ayers, the wife of Amy’s brother Shawn, has called the FBI, hoping that hearing from one of the victim’s families would sway the bureau. It didn’t.

“There are four dead girls,” Angie said she told the FBI. “Four families that have gone through 29 years of hell, and you are sitting on information.”

Barbara Ayres-Wilson, whose two daughters, Sarah and Jennifer Harbison, were killed in Austin’s infamous yogurt shop murders, says she prays that whatever is holding back the flow of information between the FBI and local investigators is soon resolved. [Ricardo B. Brazziell/American-Statesman]

Shawn and Angie Ayers are the brother and sister-in- law of Amy Ayers, who was murdered in the 1991 yogurt shop case. [Ricardo B. Brazziell/American-Statesman]

Barbara Ayres-Wilson, whose daughters Jennifer and Sarah Harbison were killed, said she prays that whatever is holding back the flow of information between the FBI and local investigators is soon resolved.

“I know there are so many privacy issues, but it has been 28 years,” she said. “Give us a break.”

The determination to find answers for the girls’ families keeps De La Fuente and the rest of the yogurt shop investigative team pushing forward despite the repeated roadblocks. In their war room, intense strategy sessions continue as they ponder other ways to access the information and chase new leads.

“I feel like we have failed them again,” De La Fuente said. “Another failure of our system. But we have not lost hope.”

Coming next Sunday

The use of family DNA in criminal investigations has prompted a debate nationally among law enforcement, scientific and judicial experts. We will explore the issues facing that new frontier in forensics.