National Veterans Memorial and Museum gives voice to veterans' experiences

As the career Army officer walks the exhibit halls of the new National Veterans Memorial and Museum he oversees, he can’t help but speak of the architecture that surrounds him, to point out the significance of the building’s intersecting, concentric rings.

There are no load-bearing columns in the 28 million pounds of concrete and more than 500 tons of structural steel that make up this new national museum. It was built as something that stands on its own — strong, solid, complete. Just like this country’s veterans, said retired Army Lt. Gen. Michael Ferriter, the president and CEO of the new museum that, after almost three years of construction, will open to the public with a special ceremony Saturday, Oct. 27, 2018, at 300 W. Broad St., in the area of the East Franklinton neighborhood known as the Scioto Peninsula.

“The building itself represents infinity, a sweeping representation of the continuous journey to defend our country’s freedoms,” Ferriter said. “Inside here, the stories that are told will infuse the veterans’ spirit, integrity, patriotism and enthusiasm for service into a community of visitors who will leave changed.”

Former Secretary of State and retired Army Gen. Colin Powell will give the keynote address, and there will be performances from the U.S. Navy band and the U.S. Army Golden Knights parachute team. Other special activities are taking place on Dorrian Green, across from the museum, and along W. Broad Street, with a processional of veterans service organizations and the Patriot Guard Riders beginning at 1 p.m. and a concert later in the day.

Free tickets to all the events and 2 p.m. ceremony had previously been claimed, though some additional provisions or opportunities for standing-room-only may have been made. Some free tickets for entry to the museum for Sunday may still be available as well. (Check online at www.nationalvmm.org/grand-opening for all last-minute information.)

This $82 million, 53,000-square-foot museum is not a historical record of any specific war, nor an homage to any particular military branch. This is not a place intended to be powered by personal collections (though there are plenty of artifacts on display). Instead, it is the first national institution meant to give voice to veterans’ individual experiences — to show the world who the sailors, soldiers, airmen, Marines and Coasties who pull on their country’s uniform every day really are, or were.

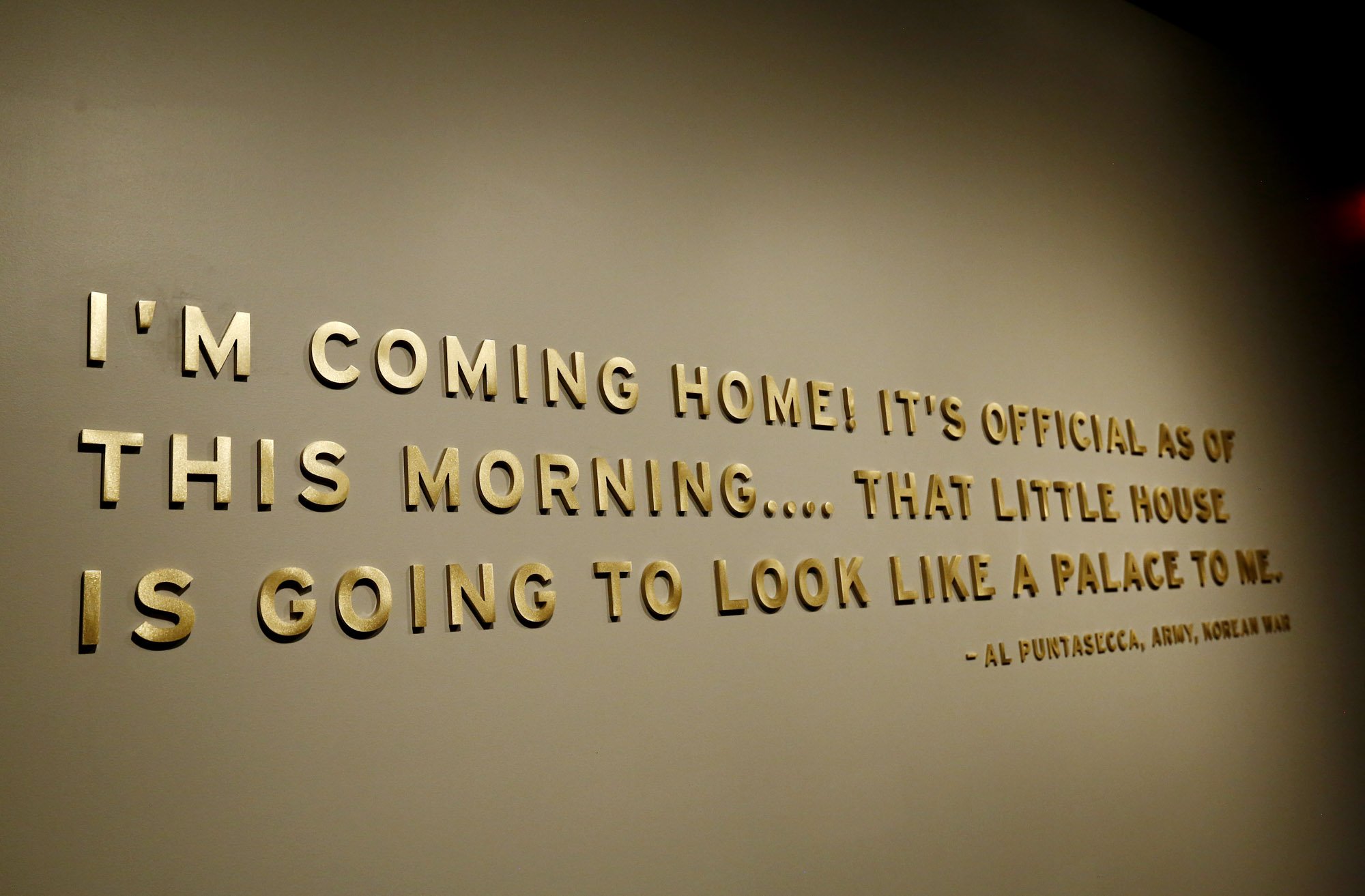

This is a reverent space, one where you can go to watch a World War II paratrooper tell what it was like to drop onto Normandy Beach on D-Day, where you can listen to the wife of an Air Force captain who spent more than five years as a POW in Vietnam recount the emotional homecoming, where you can read letters soldiers wrote to home from war zones, and where you can explore exhibits showing where U.S. troops have always served and how they train, dress, eat, work, play and sleep.

The creation of the memorial and museum — fueled by a $40.6 million contribution from central Ohio philanthropists Leslie H. and Abigail Wexner and $15 million from the state of Ohio — fulfills a vision of the late astronaut, U.S. senator and decorated Marine Corps fighter pilot John Glenn, who wanted something built here that would not only honor veterans but also educate and inspire others to serve.

“The hope is that you will leave here inspired to serve your country and your community in whatever way is meaningful to you,” said Amy Taylor, chief operating officer of the museum’s developer, the Columbus Downtown Development Corp. “The hope is that you will leave with a deeper understanding of our veterans and their lives.”

If you go

Location: 300 W. Broad St.

Museum hours (beginning Wednesday):

Wednesday-Sunday 10 a.m.-5 p.m.

Closed Monday and Tuesday

Note: The museum will be open Monday, Nov. 12, in observance of Veterans Day.

All previously released tickets for Saturday's opening ceremonies and activities were claimed. However, to see if additional tickets were released or if standing-room only space is available, or to see if any free, timed-entry tickets to the museum for Sunday are still available, visit www.nationalvmm.org/grand-opening for last-minute information.

Daily ticket prices:

Adults (18-64): $17

Seniors (65 or older): $15

Youth (5-17): $10, free to those under 5

Veterans and active-duty military (E1-E6): $12

Veterans and active-duty military (E7 and higher): $15

Gold Star families: free

(Groups of 10 or more receive a 20 percent discount)

Annual memberships are also available.

For more information:

"Something greater than yourself"

Twenty-five veterans from across the country shared their experiences in photos, audio recordings and in videos to help build the museum’s collective story. The late Sen. John McCain, a decorated Navy fighter pilot, was among them. No two featured here are the same, though love of country is the thread that carries through every inch of every hall.

Among the central Ohioans featured is Jason Dominguez. Eighteen years ago, he stood inside the Military Entrance Processing Station in Gahanna, raised his right hand and promised to defend the U.S. Constitution against all enemies. He swore allegiance to his country, pledged his faith to the same.

Dominguez, now 38, spent six years as a Marine reservist with the Columbus-based Lima Company, deploying to Iraq in 2005 as part of that storied unit that performed countless acts of heroism while suffering record-breaking casualties.

War changed him. Loss changed him. But all of it only steeled his soul to try to do good in the world that he fought so hard to protect.

To have even a sliver of his story included as part of the national museum, he said, is humbling.

“The museum helps you understand that no matter what time period, no matter what war or whether you served during peacetime, no matter what generation, our stories as veterans are similar,” said Dominguez, who lives with his wife and two sons on the Northwest Side. “Military service transforms a person forever. You have experienced what it is to be a part of something greater than yourself.”

Portraits of patriots

When visitors first enter the museum’s Great Hall, it will be hard to miss the 22 portraits suspended from the ceiling. Each is the work of Stacy Pearsall, a 38-year-old former Air Force combat photographer from South Carolina.

Through her Veterans Portrait Project, she has made some 7,500 images of veterans across 27 states. Museum designers Ralph Appelbaum Associates approached her about her work being included in Columbus.

She was thrilled.

The images are striking, with a current portrait on one side and the veteran’s military-era photo on the flip side. A nearby display kiosk offers a brief bio.

For Pearsall, who was wounded in Iraq in 2008, this is one more step in her own healing.

“I think the portrait project is special because it shows the versatility of the military community,” she said. “Only 1 percent of Americans go into service, and that 1 percent comes from all walks of life.”

Through her images you can learn about Marilyn "Mickey Newhouse" Cogswell, a Korean War-era Marine known for being fierce but who, because she was a woman, wasn’t issued a uniform. Instead, she was handed a pattern and some fabric and told to sew her own.

And you can learn about Elizabeth Barker Johnson, who during WWII was assigned to the “Six Triple Eight,” an all-black, female, Army battalion of postal clerks, truck drivers and cooks with a motto of “No Mail, no morale.” And there’s the Marine Corps boxer, the Navy photographer, the Air Force operations intelligence analyst, the Army infantryman, the Pearl Harbor survivor.

“So many stories need to be told,” Pearsall said. “This museum is a wonderful opportunity for that.”

The museum also has a temporary exhibit space, and some of Pearsall’s personal photographs from her time in the Air Force will be its inaugural display.

A life of service

For Amy Taylor, the daughter of a Navy welder, coordinating the museum project has been a labor of love.

After the opening, the development corporation will turn over operation of the museum (and the debt-free building) to the museum’s nonprofit organization. Walking away, Taylor said, will not be easy.

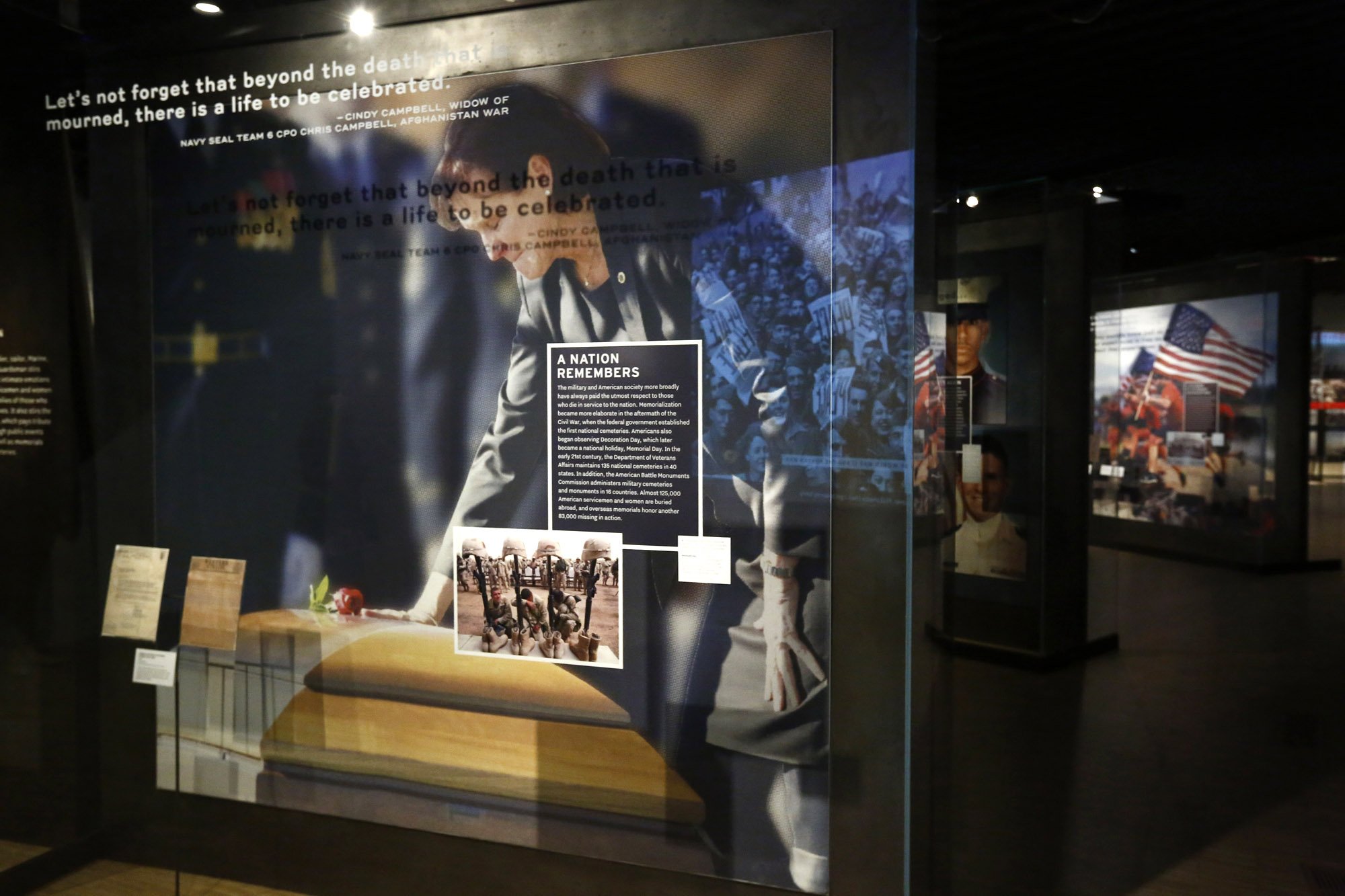

Prior to the opening, whenever she gave private tours, she always lingered in the “Coming Home” section, pausing before the photograph of a woman placing a flower on a casket during a burial at Arlington National Cemetery in Virginia.

In searching this year for significant images for the section of the museum that deals with loss, Taylor found the photograph publicly available. She was immediately struck by it: “I didn’t know specifics yet but the grief on her face, it was just so personal. I had to know more.” She sought the rights to use the photograph, and then she did a simple online search to find an address for Cynthia Moriarty, the woman in the picture. The museum sent her a letter.

One night, on her way home from work, Taylor’s cellphone rang. Moriarty was on the line from Texas. She would be honored if the museum used the image, she told Taylor. All she wanted in return? That Taylor would take five minutes to learn the story of her son, 27-year-old Army Staff Sgt. James F. Moriarty, a Green Beret who was killed along with two comrades in November 2016 while entering a Jordanian military base.

“Before the conversation was over, we both were sobbing,” Taylor said. “I went home and told my 10-year-old daughter about it. And I told her that sort of encapsulates everything we are trying to do here. Here’s this woman who suffered the greatest loss imaginable, but I was struck by what a patriot she is, how much she still loves her country. That’s a life of service. For everyone.”