Legacy of Tom Egan: 'His death has saved lives'

A faded yellow, diamond-shaped road sign with the single word "END" stands at the northernmost point of Blair Boulevard, just beyond the cracked pavement and amid the weeds.

This is where Thomas Lawrence Egan froze to death a decade ago.

At first, the news was simply sad. The body of a 60-year-old homeless man was found partly covered in snow, a half-empty bottle of liquor by his side.

Soon after, the community learned the man's name, and became aware of his background and accomplishments. The military service. The master's degree.

What came next — and continues to this day — involves a sustained, community-wide effort aimed at preventing other homeless people from dying on the streets of hypothermia.

In short, something life-saving emerged from Maj. Tom Egan's demise.

"It says something when a community just lets people freeze to death. Eugene and Springfield aren't just going to let that happen again," said Shelley Courteville, director of the Egan Warming Center program that shelters scores of homeless people at sites scattered around the metropolitan area.

"I do think his death has saved lives," Courteville said of Egan.

'A 2-by-4 to the face'

Tom Egan didn't have to die on the streets of Eugene.

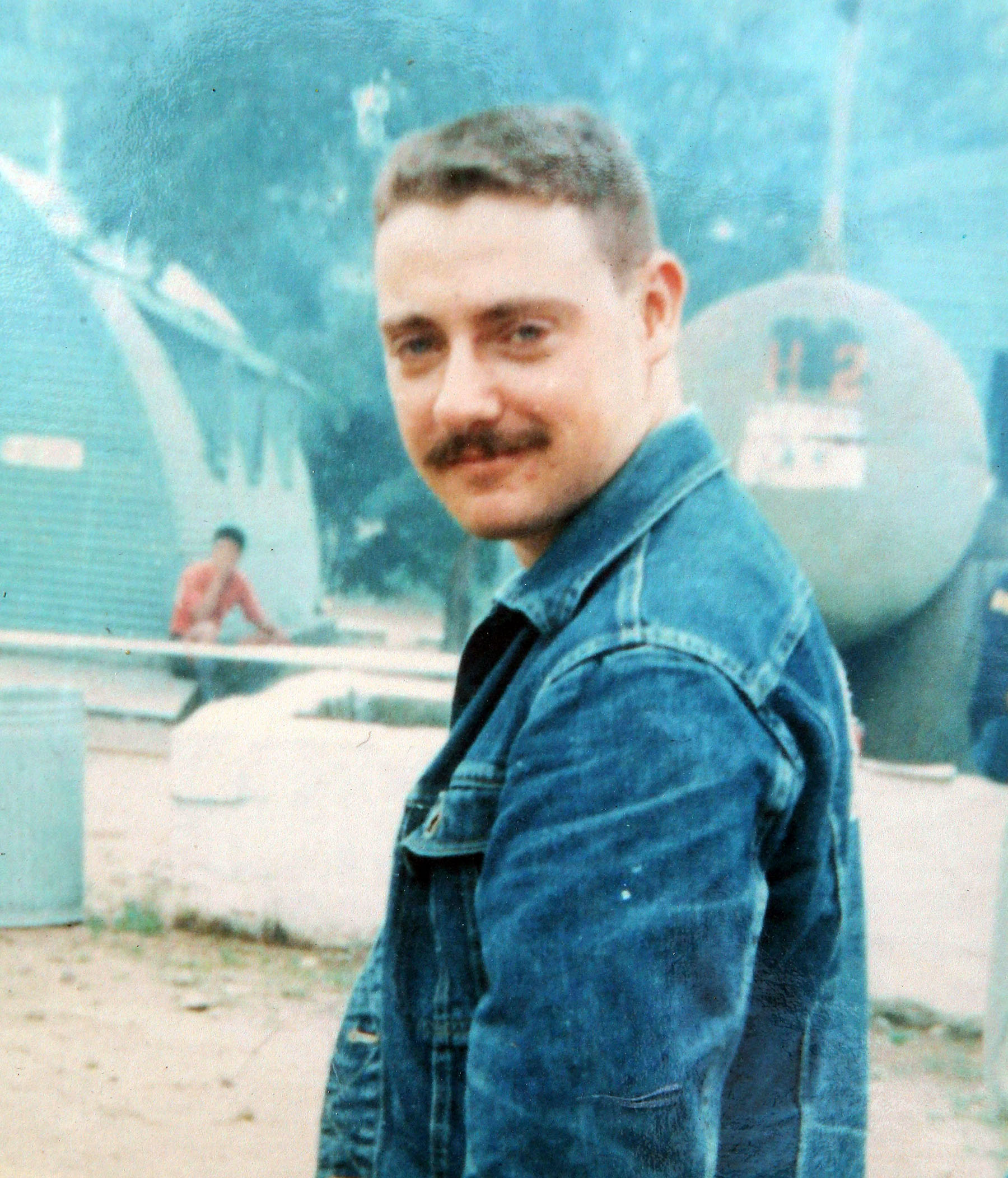

A New York native, Egan joined the Army in 1971 after graduating from Quinnipac College, later Quinnipac University, in Hamden, Conn., with a bachelor's degree in history.

He was stationed at the demilitarized zone between North and South Korea for two years before being reassigned to the Oregon Army National Guard in 1977. He attained the rank of major and went on to earn a master's degree in journalism from the University of Oregon in 1983.

He retired honorably in 1991 following a 20-year military career during which he was awarded several service medals and ribbons.

It's unclear when Egan became homeless. A longtime friend, Kate Saunders, said she always knew Egan to be a drinker, and visited him in a "squalid" apartment sometime during the spring of 2008.

Egan had no living family when he died. After his body was discovered, authorities found Saunders' contact information in Egan's pocket and called her to inform her of her friend's death. A uniformed soldier presented a folded U.S. flag to her during Egan's memorial service in January 2009.

"I knew him really well, and I found him to be very different than most people," she said. "Very brilliant, but socially inept."

Lane County Commissioner Pat Farr served with Egan starting in 1977. He recalls spending significant time with Egan and two other commissioned officers, all of whom drank. Farr and the other officers found success in their careers. Egan, however, fell out of touch with the group after retiring.

"Of all of us, Tom was the most talented," Farr said. He recalled not knowing Egan had become homeless, and said that when he read the news of his former colleague's death, "it was like a two-by-four to the face."

Days after Egan died, a U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs official told The Register-Guard that the retired cavalry officer became eligible upon turning 60 to receive $909 each month in National Guard retirement income, and also could have applied for a separate pension check based on unemployability. Egan collected monthly Social Security checks, but the amount was a pittance compared to the payments he had been entitled to as a retired military veteran.

Officials said Egan's desire to drink made him ineligible for VA housing programs that require sober living, and that he wouldn't enroll in substance abuse treatment programs offered through the veterans' agency.

"As brilliant as he was, he succumbed to alcohol," Farr said.

Egan died during an unusually long freezing snap. The low temperature in Eugene on the day his body was found dipped to 10 degrees. A medical examiner determined Egan's cause of death to be hypothermia due to environmental cold exposure.

'Work of the heart'

Just days earlier, Marion Malcolm felt an urgent need to identify a warm place where homeless people could stay overnight during the cold stretch.

"I woke up one morning and said to myself, 'People are going to die,'" Malcolm said. The Springfield resident and longtime community organizer said she and others with the Community Alliance of Lane County started working the phones. They were able to get the First Baptist Church in Springfield to open its doors to the homeless. Two other churches followed suit. They collectively hosted guests for six subfreezing nights that December.

At some point during that initial activation, word trickled through to Malcolm and others involved in the endeavor that Egan had died.

"We weren't surprised," she recalled. "It seemed inevitable. It was too cold to be outside."

By February, a push by local citizens, nonprofit agencies and government agencies led the Lane County Board of Commissioners to designate the county-owned National Guard armory in Eugene as a cold-weather shelter through March 31. The group in charge of operating the shelter also came up with a name: Extreme Weather Accommodations Given All Night, or the EGAN Shelter Coalition, for short.

"We already were putting together the pieces (when Egan died) and I'd like to think it would have been successful anyhow because we were already underway in Springfield," Malcolm said. "But I do think his death and the publicity around his death certainly served as a catalyst" for the project's continued success.

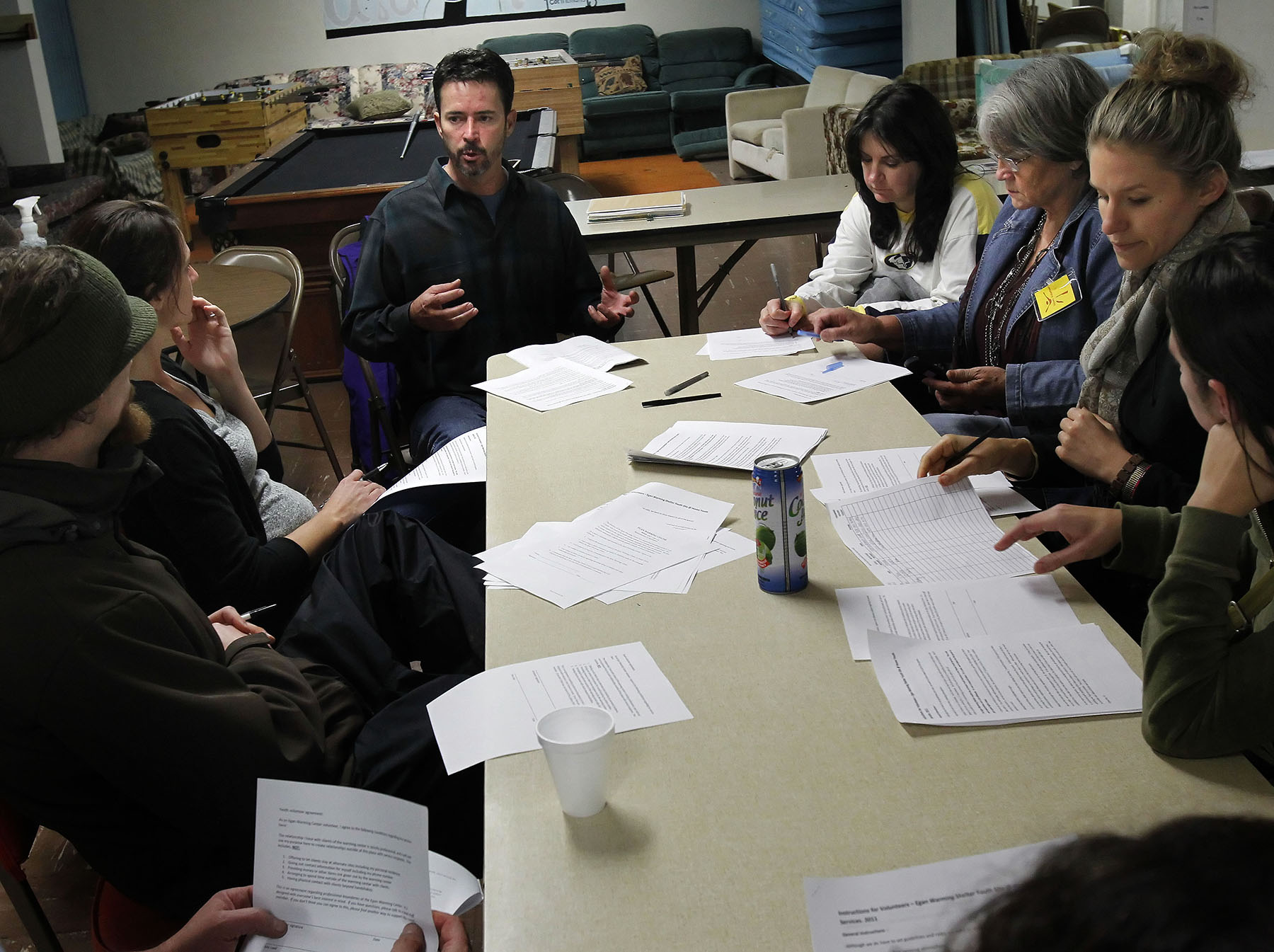

St. Vincent dePaul Society of Lane County ultimately took on administration of the warming center project, which this year includes 10 sites that opened for five consecutive nights earlier this month. Activations happen whenever overnight low temperatures are forecast to be 30 degrees or colder. Over the last decade, the sites have been used up to 25 nights annually. Last year, more than 1,100 volunteers put in more than 22,000 hours with the program.

'"This is work of the heart," said Courteville, the warming center's director. She said she worked 105 hours during the five-night activation in mid-December, and has a goal of adding about 1,000 volunteers to the roster.

Courteville and Malcolm emphasized that homeless people are "our neighbors" and likened the warming center volunteer experience to a gift exchange.

"What we provide is the gift of a warm space and a listening ear," Courteville said. "And when a guest shares a piece of their story, that's a gift to us."

Lessons learned

Farr and Saunders said they believe Egan would have used the overnight warming shelters had they been open while he lived on the streets. Egan Warming Center sites are what's known as "low-barrier" shelters that allow intoxicated people to stay so long as they don't use alcohol or drugs while on-site.

"We have plenty of people who suffer from the same thing that Tom did who stay at the warming centers," Farr said. "But I think Tom would be shocked to know" that his name is now attached to the program.

"Tom's death became a tangible reason to support it," Farr added in response to a question about how the program has been able to survive and grow over the last 10 years. Lane County, through the Human Services Commission, this year is providing more than $35,000 in funding along with another $39,515 for a seasonal coordinator at St. Vincent de Paul. Nonprofits, social services agencies, local businesses and individual donors also support the program.

Some also say there's a direct link between Egan's death and increased support in recent years for projects designed to help the homeless population.

"Our collective consciousness was raised, that there needs to be more done" to help the homeless, Pastor Dan Bryant of Eugene's First Christian Church said last Monday at a candlelight vigil marking 10 years since Egan died. Annual remembrances have been held at the place of his death, and the First Christian Church has long been a warming center site.

Local advocates — and county officials, for that matter, who acknowledge a lack of beds leaves more than 1,100 people unsheltered in Lane County on any given night — say much more help is needed to ensure the safety of homeless people. Some, like Malcolm, assert that all people have a basic human right to sleep at night, which is consistent with language included in the Universal Declaration of Human Rights adopted in 1948 by the United Nations General Assembly.

Farr agrees with that idea, and has publicly advocated for getting more homeless people into permanent, supportive housing. He agrees that the death of his friend in 2008, while tragic, has aided the conversation about helping the homeless.

"Historically, there's been a lot of hand-wringing over the issue," Farr said. "But a lot of lessons have been learned from whatever led Tom to the end of Blair Boulevard that night."