Suffering on Sullivant: Part 3

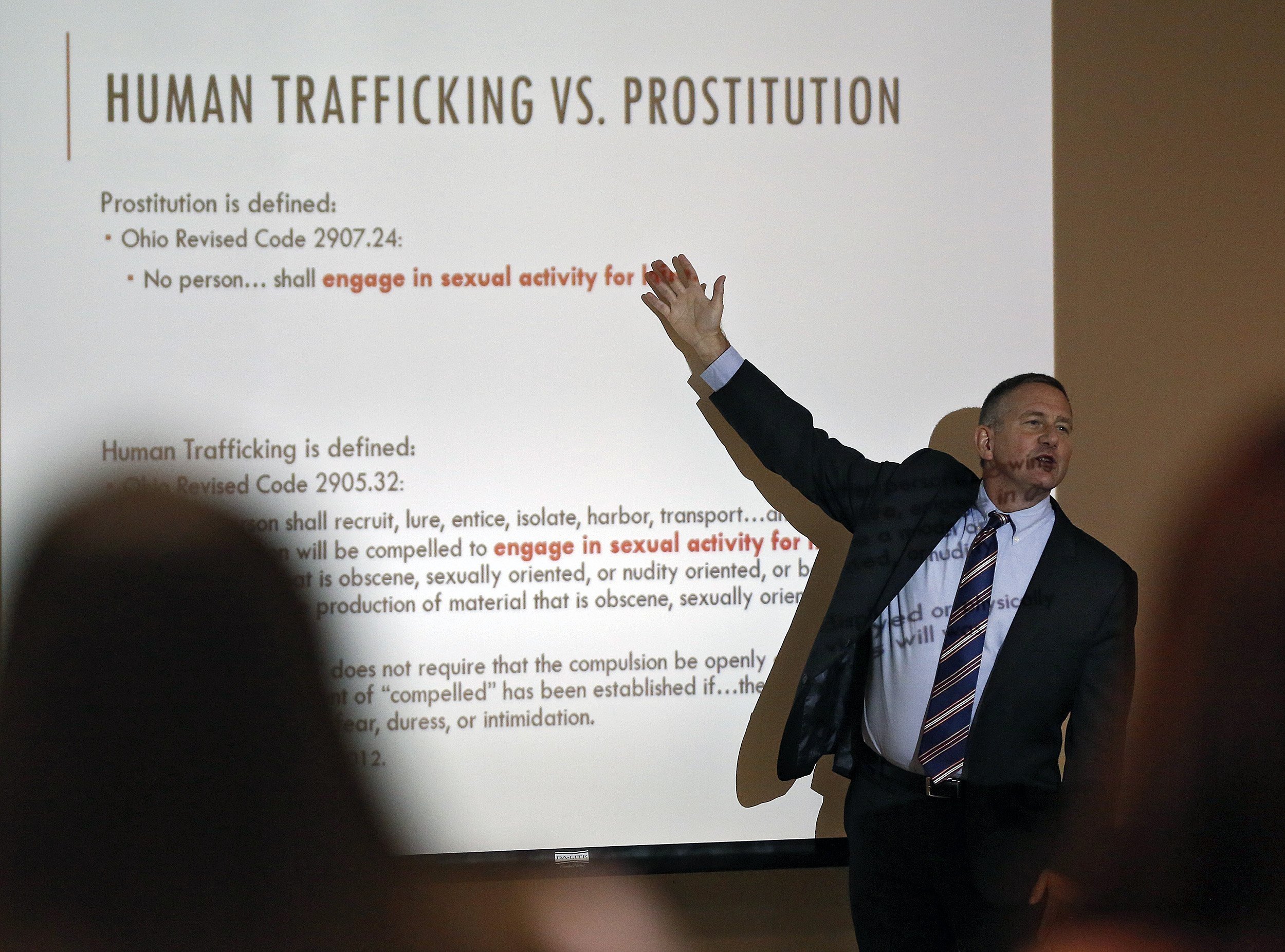

Most of the 90 or so Columbus police officers being considered as replacements for the division’s disbanded vice unit leaned forward in their seats as the photos flashed on a giant screen.

The images were startling: On the left were images of unkempt women with hollow cheeks, bruised faces, vacant stares. On the right were photos of the same women, except that each one now flashed a smile that reached her clear and sparkling eyes.

Each had been charged with prostitution and had successfully graduated from Franklin County Municipal Court Judge Paul Herbert’s specialized-docket CATCH Court (Changing Actions To Change Habits), which uses intensive probation and programming to help victims of human trafficking recover and leave the lifestyle behind.

Among the women on the screen were new college graduates, a law firm receptionist, business managers and a court bailiff.

Herbert pointed to the photos and asked the officers, “Was that change worth it? Was the transformation of these women worth a different approach by police?”

Many nodded.

Herbert, his court staff and four CATCH graduates were part of a two-day training held in August for the new Police and Community Together team (PACT) that replaced the troubled vice unit that was dismantled earlier this year. Commanders say that the new methods officers will employ will better tackle problems such as prostitution and human trafficking that affect the quality of life in neighborhoods, especially the Sullivant Avenue corridor through Franklinton and the Hilltop.

Commanders agreed that the session on human trafficking was a priority for the officers, who hit the streets earlier this month in a slow rollout of the new policing program.

PACT officers will rotate assignments rather than entrench in a neighborhood. And when tackling vices such as prostitution and human trafficking, they will employ a different approach of trying to get the women into CATCH Court and get them the resources they need. Officers also will focus on the johns — the majority of whom are married, educated, suburban men, statistics show — and work to end the demand for prostitutes as well as the supply.

Helping the PACT officers better understand that the women on the street are human trafficking victims in active addiction who need help is a big part of the change, one that activists say could go a long way in transforming the Sullivant Avenue corridor.

“This is a new era of policing to the division,” interim police Chief Thomas Quinlan said. “We’ve been laying the groundwork for this for a long time. We’ll be making a difference in the neighborhoods.”

An answer or a Band-Aid?

The young woman clutched a fork in each hand, her face just a couple of inches above the paper plate as she alternately scooped up the homemade macaroni and cheese and greens drowned in ranch dressing.

She was exhausted, sunburned and sweating from the relentless summer heat. She spoke to almost no one, but her eyes darted around the crowded kitchen as if she were a field mouse keeping watch for a swooping hawk, because often someone steals everything she has: her food, her clothes, even her body.

But not here, in the drop-in center on Sullivant Avenue run by Esther Flores, an advocate on the Hilltop and in Franklinton who founded the nonprofit 1DivineLine2Health and works tirelessly to help the homeless, those in addiction, and victims of human trafficking.

For a couple of hours each Thursday night, this young woman and as many as 40 others like her who roam the streets of Franklinton and the greater Hilltop, leave most of their fears at the door of the tidy, two-story house on Sullivant Avenue near Burgess Avenue.

Each crosses this threshold bearing the weight of a tragic backstory. They are young and old, some strung out, some clear-headed and simply excited to catch up with the volunteers they have come to trust and love. Yet almost all are reed-thin and nervous. Few, if any, have felt kindness and love before entering this house with its calming vibe and warm-colored walls.

Volunteer April Caudill, who lost a stepdaughter to an opioid overdose, greets each woman with a hug.

“Oh, it’s so good to see you,” she tells a 29-year-old woman who comes each Thursday and signs in only as “Tae.”

Tae and the others almost all make a beeline first for the racks of clothes and shoes along the wall. A few of the women are the “lucky ones,” lugging a cloth bag or strapping on a backpack that holds everything they own. But many come with nothing, eager for a change of clothes on this day and something as simple as a toothbrush and a fresh pair of underwear.

Three such centers operate for a few hours each week on Sullivant Avenue, and two more — both first-of-their-kind, 24-hour centers — are in the works. The Love Drop-In Center hopes to open by the end of the year on the Hilltop, and Sanctuary Night plans to open in a renovated building in Franklinton. The centers can be lightning rods when it comes to discussion of solutions on how to clean up Sullivant Avenue.

When the Greater Hilltop Area Commission debated one of Flores’ drop-in centers earlier this year, some residents objected.

“More addicts will be coming into our neighborhood because it is free here,” one neighbor told the commission. And Hilltop activist Lisa Boggs, who runs a successful street outreach program, says the drop-in centers that focus on harm reduction don’t do anything long-term.

But Flores, a registered nurse, said that what matters most is keeping those who visit alive until they can finally choose recovery and it sticks.

On that August evening, a woman Flores had never seen came to the center. The woman's feet were caked with dirt and dried blood from the blisters that covered them. Flores filled a hospital pan with warm water and grabbed a bag of gauze and a washcloth. She slipped on latex gloves and cradled the woman’s left foot in her hand. She guided it into the pan, then did the same with the second. Instantly, the clear water turned a swirl of red and brown.

Whimpering like a wounded child, the woman told Flores that it hurt too much to go on. She rocked back and forth and hugged her arms to her chest and moaned.

Flores told the young woman, in a soft and lyrical voice, how Jesus had washed the feet of his disciples.

“We have to do this, baby. We have to," she told the woman. "It’ll help you. I will help you. We love you.”

Later, she explained: “I believe everyone has a point where they can be healed — mind, body and spirit. We will be here every week until they are ready."

Flores hopes the Columbus Division of Police’s new PACT team will make a difference along Sullivant Avenue. However, the frequent and outspoken critic of Mayor Andrew J. Ginther and his administration is adopting a wait-and-see approach.

“As Franklinton gentrifies, we’re seeing a migration of the women on the street moving farther and farther west down Sullivant,” she said from the barren living room of a recently donated house she plans to turn into a full-time center. As she speaks, at least six women she serves walk past the house. It is noon and raining. Flores shakes her head and said she hopes they are OK.

Robin Davis, a spokeswoman for Ginther, said the city already has done much work in the area. She pointed out investments in programs such as the police Safe Streets initiative, the Shot Spotter gunshot-detection system, and the neighborhood crisis response program, a multi-department effort that coordinates city resources to install streetlights in alleys and deal with nuisance code problems.

She acknowledged that more needs to be done, but said the city has been involved in a yearlong process that involved Hilltop residents as everyone looks for ways to beat back poverty and crime. Those new initiatives and strategies are expected to be rolled out next year.

Jason Reece, an assistant professor in the city and regional planning program at Ohio State University, said the problems that plague Sullivant are not easily solved.

"There is a perception issue with things that emerge in terms of how the community starts to view this corridor, the reputation it develops," he said. "Then it becomes a self-fulfilling prophecy."

He said law-enforcement cannot be the sole solution: "It's really about prevention that's more oriented toward meeting whatever needs individuals have that are out there on the streets."

Stories that inspire. Coverage that informs. Investigations that affect change. This is real news - just when it's needed most. Support The Columbus Dispatch.

Subscribe

“There has to be a solution”

Barb Davis has spent more years of her life selling her body for sex than not, and the past 15 years were spent working the Sullivant Avenue corridor and the West Side.

She slept in the bushes and in vacant houses known by those who use them as “abandominiums.” She ate out of trash cans and stole from thrift stores. She has been stabbed, shot, kidnapped and raped. And if you look closely, you still can see shadows of the scars of the now-removed tattoo where her trafficker had branded his name across her chest. And whenever someone hurt her, she said, the police didn’t seem to care.

“We’re prostitutes. They see us as the bottom of the food chain,” she said. “They look at what happens to us and think, ‘Well, she brought this on herself.’”

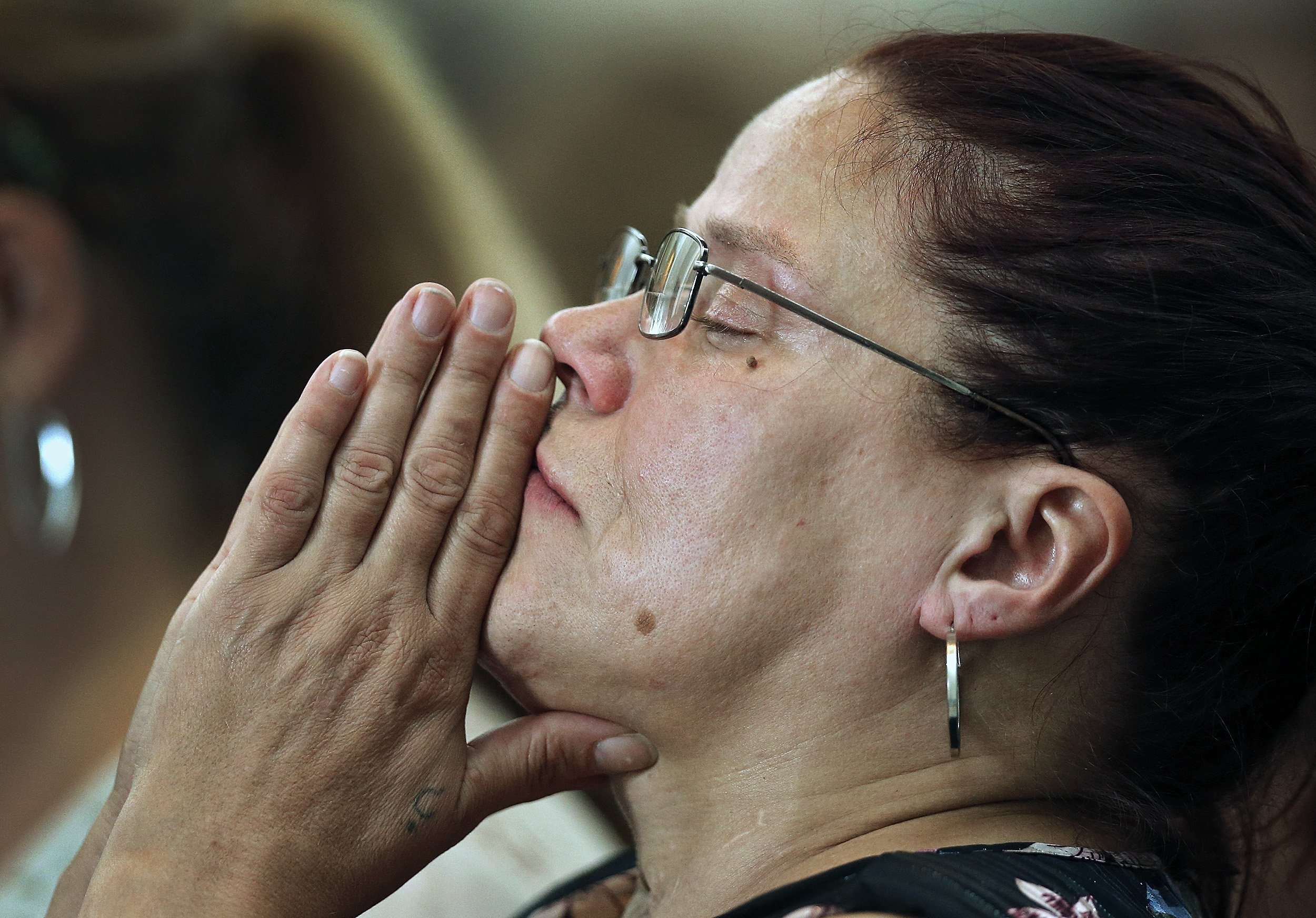

Coming up on two years of sobriety, Davis said she will never completely erase the scars that the neighborhood wrought upon her.

“At any given time, I can close my eyes and be right back at that corner of Sullivant and Central. I can see it and smell it and feel it,” said Davis, who turns 50 this month. “Now that I am sober, I can see all the brokenness out here so clearly. It makes me so sad.”

Davis spends her Sundays now visiting women in the neighborhood, delivering bags of personal hygiene products and snacks.

Like Flores, she wants to be hopeful that the Sullivant Avenue corridor can be improved.

“The West Side needs a lot of tough love,” Davis said. “People need to stop looking the other way.”

She has high hopes for the new methods that Columbus police say they will employ and thinks more drop-in centers, additional ready access to treatment, and services for the homeless right there in the neighborhood would help. Because, she said, bringing hope to the streets and making those who run them feel valued is the first step in transforming the neighborhood into what it can be.

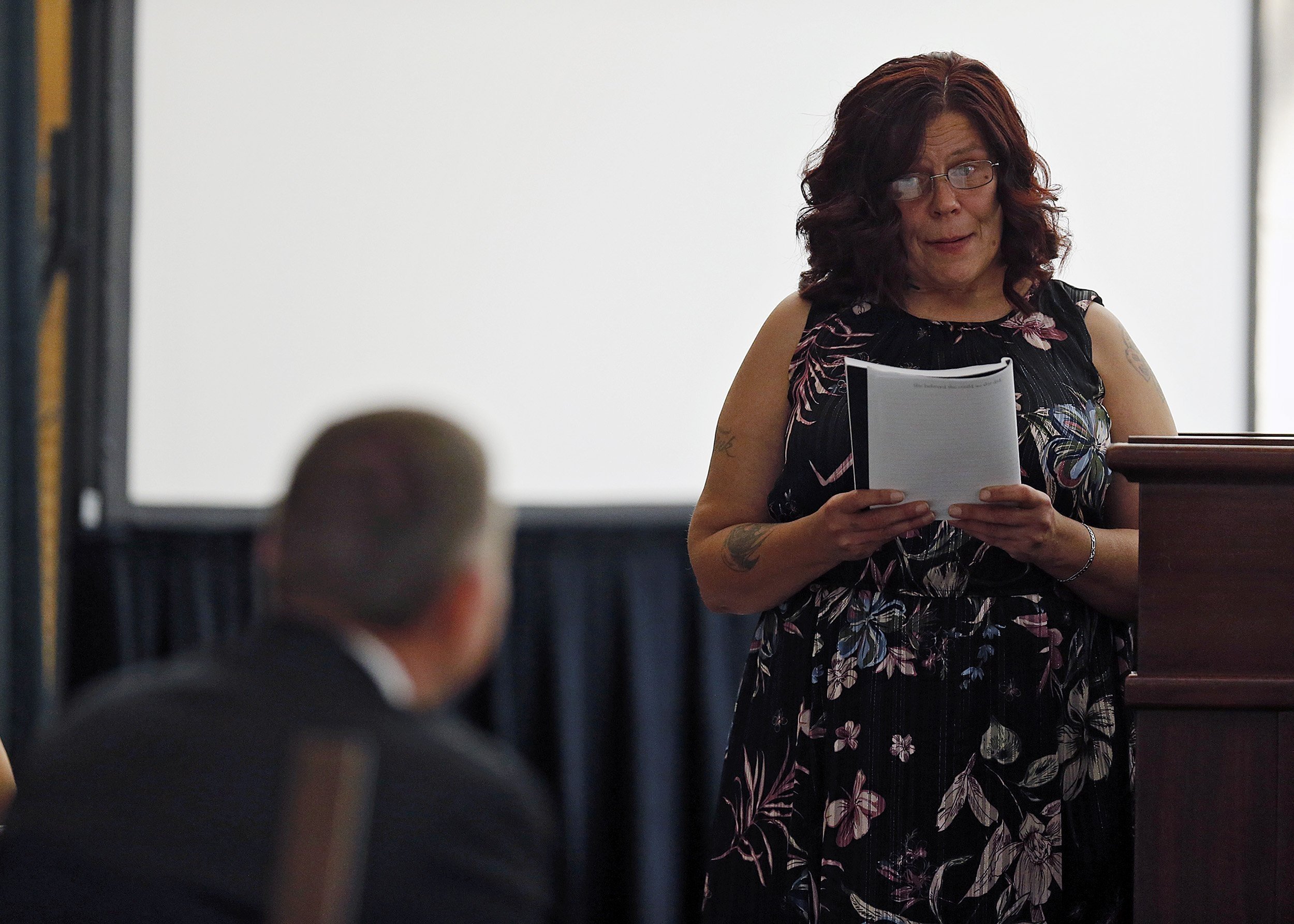

She likens it to her own reincarnation. In September, she found herself in a place she never thought she would be.

She walked into the Statehouse atrium wearing a flowered black maxi-dress and with her hair freshly styled in a shoulder-length bob. Her smile grew wider with every step.

As she was introduced at CATCH Court graduation, the crowd cheered louder for her than for most. That was because logic dictated Davis’ lifestyle should have killed her a long time ago.

Instead, there she was, accepting a diploma from Judge Herbert.

In introducing Davis to the crowd, court probation officer Gwen England said she couldn't count the number of times she had heard someone tell Davis, "I thought you were dead," because they no longer saw her on the streets.

"The fingerprint you have left on Columbus and CATCH Court is hope," England said to Davis.

Davis fought back tears as she thanked those who have supported her, even in her darkest days. She thanked her brother and sister who "taught me the real meaning of family."

Before her graduation, reflecting on the neighborhood that hurt her so badly, Davis said she hopes its transformation can mirror her own.

“There has to be a solution to what happens on Sullivant. People just need to dedicate to it,” she said. “People out there aren’t bad people. They are sick and need help. And everyone deserves kindness. If you can’t say something kind to them, at least pray for us. And pray for our city, too.”

Dispatch Reporter Patrick Cooley contributed to this story.