Rolling Along: Bowling industry tries to reverse its downhill trend

On a late-summer Friday afternoon, just after lunchtime, Gary Alberado sat on his perch behind the main counter at Ormond Lanes.

The general manager and co-owner, who bought the Ormond Beach bowling center two years ago, could look to his left and see 14 lanes filled with senior bowlers from a weekly afternoon league. To his right, a smattering of non-league bowlers occupied several of the remaining 26 lanes.

Over Alberado’s right shoulder, the front doors opened as a small bus unloaded about two dozen kids — all in the 5-year-old range — who paraded through the entryway and made a quick right turn toward the bar at the end of the building.

Oh, wait. Alberado has an update.

“We put in a laser-tag room back where the bar used to sit empty all the time,” he says. “We moved the bar out onto the main floor, and today we have a day-care coming just to do laser tag.”

It’s all part of the new normal for the ol’ neighborhood bowling alleys. At least those that prefer to remain open and, hopefully, profitable.

The modern business model includes a healthy mix of league bowlers, off-the-street bowlers and, basically, “other stuff.”

“It was so easy back in the day. Just open the doors and turn the lights on,” says Scott Newell, co-owner and operator of Sunshine Lanes in DeLand. “Some people evolved, some didn’t.”

Newell turned part of Sunshine Lanes into an arcade, alongside a cordoned-off set of lanes for private events. Up front, facing U.S. Highway 92, a Johnny Rockets burger joint rents the space.

On weekend nights at most bowling centers, the lights are lowered, the music is jacked, and the drinks are flowing. That’s been the norm for more than a generation, but nowadays, a traditional bowling establishment like Ormond Lanes — and Volusia-Flagler’s other four operations — must go beyond just the weekend nights to tap new revenue streams.

The old industry standard was a 70-30 revenue split. Leagues provided the 70 percent, which always paid the rent, with the 30-percent “gravy” coming from walk-in bowlers and food and beverage. Now, locally, the goal is a 50-50 mix of traditional league play and the gravy.

“There are places where you can quickly increase revenue without putting it on the backs of the league bowlers,” says Alberado.

And that’s a good thing, because league-bowling isn’t exactly a growth industry.

The Shrinking League Base

Ralph Kramden and Ed Norton were on bowling teams. So was Archie Bunker. Fred Flintstone and Barney Rubble, too.

But it wasn’t just in pop culture where league bowlers showed up. In the decade or so after World War II, especially after the automatic pin setters became commonplace, and especially in suburbs where blue-collar America dominated the exploding middle class, bowling centers and bowling leagues were everywhere.

This was especially true in the colder, industrial, northern boom towns, where outdoor activities were restricted by weather issues, and at a time when indoor activities were certainly more limited than today. By the mid-1960s, industry research shows there were about 12,000 bowling centers in America with nearly 10 million regular bowlers.

But in the decades since — slowly at first, but then at a much quicker pace — the numbers retreated. Bowling bags went from your parents’ car trunk to the hall closet to the attic. The sport didn’t necessarily slump all the way to the gutter, but that wonderfully deep cracking sound — the oh-so-recognizable noise of 10 pins sent flying by a pocket-perfect roll — grew more and more faint.

One way to measure the number of serious bowlers is to note the membership in the U.S. Bowling Congress. Forty years ago, membership was 9 million, today it’s about 1.5 million. Also 40 years ago, according to the USBC, the country had 9,000 certified bowling centers, compared with 4,300 today.

Sitting behind the counter at Ormond Lanes, Alberado smiles and shakes his head at the reaction to the downturn.

“The bowling industry panicked, thinking something was wrong with them,” he says. “What happened was, into the ’80s and ’90s, you could do things at home that you couldn’t do before. You could rent movies and watch movies at home. Computers came along. You had cable. People have home entertainment that they didn’t have back then.

“That’s what happened to league bowling. People are bowling two nights a week instead of four nights a week. You used to have full nights of league bowling, every night. Two shifts.”

Newell, who grew up in the DeLand area, did well on the local tournament scene and eventually bowled regularly on the PBA Tour, where he still competes in a handful of events each year. He turned his attention to his hometown bowling center three years ago and says the 800 current league bowlers is down from the high-water mark of about 1,500, 20 years ago when the center had 32 available lanes instead of the current 20 — plus eight that are now set aside for private functions.

Those eight “boutique lanes,” along with the adjoining arcade and party area, help make up the void caused by the industry-wide loss of league revenue, caused by the industry-wide loss of league bowlers.

The new industry standard — or at least a goal — of a 50-50 financial split between league play and everything else may soon become 45-55, 40-60 or even more in the other direction.

“But you still have to have a league base,” says Rob Onusko, general manager at the AMF Deltona Lanes, which along with Ormond Lanes is one of two 40-lane centers locally. “It’s not just that they’re here bowling, they’re here eating and drinking for 36 weeks.”

Yes, 36 weeks. The traditional league-bowling season practically mirrors the public-school calendar, with shorter summer leagues filling the void between seasons. A league team has four bowlers, but also has one or two subs on call because, say, every Monday or Tuesday night for 30-plus weeks is quite a commitment.

Too much of a commitment for some, it seems.

It’s How They Roll

Awaiting the start of play in his Monday night league at New Smyrna Lanes, 76-year-old George Sewell explains why he stuck with bowling and never ventured toward a golf course, as so many other retirees are prone to do.

“I roll my ball down there and it comes back to me. Every time,” says the retired Daytona Beach fireman, who grew up in Poplar Bluff, Missouri, and moved here in 1967.

On this particular Monday, the 16-lane bowling center (the area’s smallest) is filled with league bowlers, as it usually is.

“I get a lot of comments from our bowlers saying they like the intimacy of this place,” says New Smyrna Lanes manager Juanita Binder. “Every day we have leagues, every night we have leagues. There’s always room for one more player. Come hell or high water, if you want to bowl, I’ll get you in.”

The other local bowling centers are also generally busy with league play most nights. So, you might wonder, what’s the issue? Well, back when George Sewell first started bowling here, most places were doing two shifts of league bowling each night — one at 6:30, the next at 9. These days, just one shift, and not always employing all the lanes.

Sewell puts part of the blame on rising costs, which can hit particularly hard in a sport whose demographics don’t skew toward country-clubbers.

“It used to be very cheap to bowl,” he says. “People came, bowled, drank a few beers, had a great time.”

For non-league, open-bowling, area prices are mostly in the $3-4 range per game, with shoe rentals between $2-4, but time-limit specials are available at most centers, and some offer late-night deals.

Leagues charge each bowler a “lineage fee” each night of play. It’s usually in the $20-plus range, with about two-thirds of that going to the house and most of the rest to the league’s prize fund. Those “money leagues,” where the top two or three teams at season’s end win the bulk of the prize money, have taken away some of the fun, some say.

“Used to be 14-15 bucks per night, a basic prize fund, buffet and trophies at the end,” says Mike Russell, who lives in Holly Hill and bowls as a sub in DeLand’s Thursday night league. “It was basically a night for everyone to get together.

“Once these money leagues came about, now you have your sandbaggers, people wanting to run brackets and money pots. It took more of the fun out of the game because people started obsessing about money. We pay $22 a night. For the average person, that’s a lot to spend on three games of bowling for a couple of hours.”

But still very much worth it for others.

“I like the competition, but I also like the camaraderie,” says Port Orange native Newt Nicholson, 58, who started bowling in the mid-’80s. “It’s one night a week, trying to win, but being with the other guys, having a couple drinks.”

One unique problem for the better bowlers, like Nicholson, who usually carries an average of 200 or better, is how much easier bowling has become over the years. Strategic placing of lane oil makes it easier to put your ball in the pocket and harder for it to leave it, and modern engineering produces bowling balls built to provide varying degrees of hook, depending on the bowler’s desire.

“I think the better bowlers liked bowling in the old days because it was more competitive,” Nicholson says. “But now, it’s still competitive, but it’s too easy. They’ve made it too easy. To me, the hard part is repeating shots. League shots are usually more forgiving.”

What’s a bowling operator to do, though?

“If I make my lane conditions tough,” asks Newell, “and the guy across town makes his easy, guess who’s gonna have the most bowlers?”

Harder to Hook Them

Most suggest the culprits for the generational shrinking of league numbers are the time commitment and, more broadly, the way people make use of their free time.

“They have a lot of young people down here for open-bowling, but you can’t get them into the leagues. It’s a commitment,” Sewell says. “In our league, you’re committing for 33 weeks.”

Michael Johnson, Sewell’s teammate, is a 60-year-old retired federal government worker who first learned to bowl in his youth in South Dakota. He senses the same things as Sewell.

“I’d say the biggest issue is just the general interest in bowling,” he says. “I think people like to go bowling maybe once a month, but that time commitment for a league ...”

Josh Allman grew up in the New Smyrna Beach area, bowled on the high school team, and bowls in leagues year-round, two nights a week. He’s just 29, which means he stands out a bit on a Monday night where the NSB Lanes is filled with 64 men and women bowlers, almost all of them older.

“One ... two ...,” he begins, looking around between his turns to roll. “Three ... four ... five. There are five of us here tonight under the age of 35. I know people my age who like to go bowling, but don’t want to bowl in a league. They go with other ventures. They might think it’s an old person’s sport.”

Beyond expenses and time commitments to be a league bowler, the bowling industry is fighting what so many other recreational and entertainment industries are fighting. Today’s world is full of shiny objects to grab your attention.

The pie is split into ever-thinner pieces. It may be why, in Volusia County, today we have four “traditional” bowling centers when we had five last year, six a decade ago, and seven a decade or so before that.

Halifax Lanes in Daytona Beach, Daytona Bowl (formerly La Paloma) in South Daytona, and Bellair Lanes on Daytona’s beachside are gone and, in Daytona Bowl’s case, flattened. That leaves two on Volusia’s east side, two on its west, and Palm Coast Lanes in Flagler County, plus the new GameTime at One Daytona, which includes a sports-bar restaurant, large arcade, and 12 lanes for bowling.

According to Alberado at Ormond Lanes, there’s good news and there’s bad news regarding the reduction in traditional bowling centers.

“Here’s what’s important,” he says. “Bowling centers don’t really compete with each other. They compete with other entertainment. The more bowling centers you have in your community, the stronger bowling is in that community. When a center closes in a community, the other centers might pick up some business, but overall it’s bad for bowling.”

The Boutique Factor

The lone new addition — Game Time — is part of a trend, particularly in larger metro areas, where bowling lanes are often just one part of a complex that might include bocce, ping pong, an array of large-screen televisions, plus full-service bars and restaurants.

Instead of a bowling alley with food and drink, they’re more like sports bars with some lanes. The bowling industry isn’t complaining.

“It’s all about bowling,” says Chad Murphy, executive director of the U.S. Bowling Congress. “Giving people of all ages the opportunity to discover, or possibly rediscover, the enjoyment of knocking down pins and competing with friends is the most important factor.”

Those entertainment/bowling centers are in the same realm as TopGolf: Hip, low-pressure, casual alternatives to the “real thing.” Except with the boutique bowling centers, the actual bowling is just as it is at the nearest traditional lanes, where TopGolf is like real golf only in the use of clubs and balls with targets.

In time, such trends could pay off for the bowling industry, because if young people discover a love of bowling and want to play again, they may find a more traditional bowling center, where the cost to bowl is generally much lower than you get at the boutiques.

“When things are new, people don’t think about what they spend on it,” says Alberado at Ormond Lanes. “But after that first time, price becomes an issue.”

Meanwhile, many bowling alleys are trying to incorporate a bit of boutique in their own surroundings.

“I don’t think there’s anything wrong with doing that,” Newell says, pointing toward the far north end of his Sunshine Lanes. “I have eight lanes down there in front of the bar that we don’t particularly use for leagues. That whole side of the building is meant for Friday and Saturday night — people eating and drinking while they bowl and having a great time. They don’t care about their score. Nothing wrong with that. You gotta have both.”

And even though AMF Deltona Lanes hasn’t cordoned off a section of its 40-lane center, on weekend nights the whole place incorporates a completely different vibe.

“We’ve got black lights on, music going, a lot of energy,” Onusko says. “It’s entertainment. It really is.”

Is the Comeback Afoot?

It takes more than flash and dash to lure and keep business, regardless of what you’re selling.

“It’s not just the bowling industry, look at all industries,” says Newell. “Look at McDonald’s. When you walked in there in the early ’90s it was white, yellow and red tile, and not necessarily the cleanest place. Now you walk in there, it’s wood grains, it’s marble tops. Chick-fil-A drove some of that. Starbucks changed Dunkin’ Donuts.

“Look at movie theaters. How many do you see in the back of a shopping plaza with movies at $7? You don’t see that anymore. Everything has evolved.”

And everything will continue evolving, which means there will be winners and losers. Newell has seen bowling at the narrowest of local levels, as a youth bowler, as a league bowler and as a professional at the highest level, bowling at many of the biggest and best bowling centers in America. Now he sees it as an owner/operator in DeLand, and while his eyes are wide open, he’s hopeful.

“I don’t think the traditional bowling will ever die,” he says. “If anything, it will figure out how to evolve and maybe come back even stronger. If that’s the case, guys like me, we may be sitting in the catbird’s seat.”

No guarantees, however. When you’ve lost the numbers bowling has lost, you cling to new business models that are working and hope they grow. But as much as the industry has changed in just a generation, it may have to continue changing constantly to keep any semblance of a roll going.

Come back stronger? Is there really a chance? Newell shrugs.

“It’s hard to say, really. Anyone who claims to have all the answers is lying.”

Some things you might not know about bowling

Modern balls and lanes

Modern bowlers, like modern golfers, have been helped greatly by technical advances in equipment. The best modern bowling balls are made with materials and weight-distribution technology that can be fitted to a bowler’s desires and strengths.

“When you had to use rubber balls or urethane balls, you had to physically do a lot to the bowling ball to get it to the pocket, especially to strike,” says Sunshine Lanes co-owner and operator Scott Newell. “Now, guys can curve the whole lane, and they couldn’t have done it with those older balls.”

Also, advances in the application of lane oil allows bowling centers to put down a pattern that promotes a roll into the “pocket” (between the head pin and the pin to its right, for right-handers), which is the best way to achieve a strike. This can give a false sense of achievement, says Newell, a DeLand native who has bowled on the PBA Tour since 2008.

“There’s this perception, ‘I bowl 230 in a league, and I see a guy on TV bowl 230 ...’ Well, we’re not bowling on the same conditions.”

A league average of, say, 215, will likely translate to about 175 or so on the less-friendly professional lanes.

“Maybe not even that high,” says Newell.

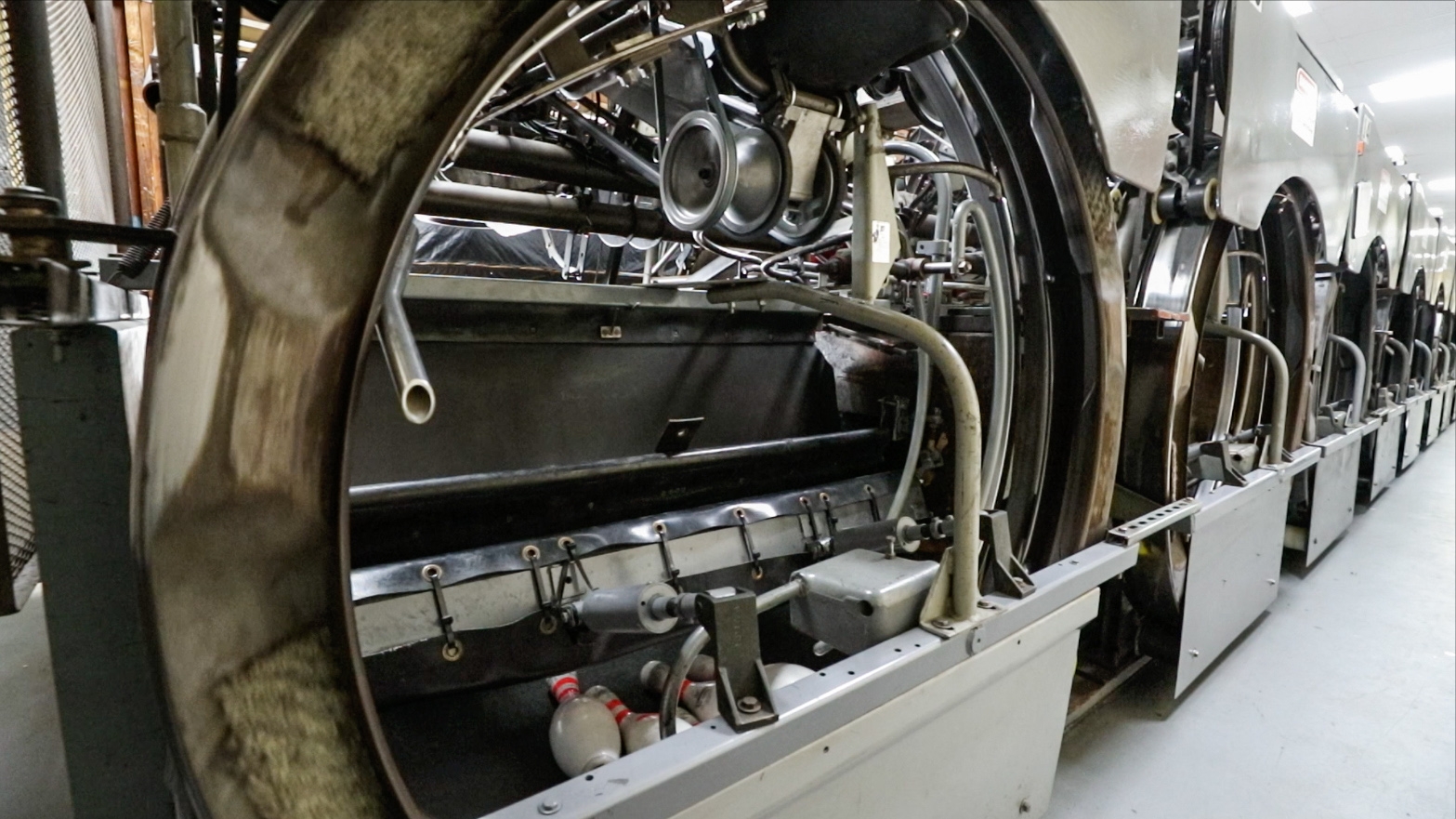

Pin setters

Modern technology has naturally brought advances in the backstage machinery that sweeps “dead” pins away and sets up a new batch of pins between frames. But at New Smyrna Lanes, owner/operator Steve Calabro is proud of his 16 pin-setting machines that have been in use since the center’s opening nearly six decades ago.

“They were built in 1959 by Otis Elevator in Chicago,” says Calabro, who bought the New Smyrna center in 2008. “Brunswick needed to get automatic setters but didn’t have the means, so they contracted Otis to manufacture them. It’s basically a glorified clock. Everything is timing. Very little electronics in them.”

Below the machinery is a piece of carpet that catches the pins and, through slight shaking, delivers them to a wheel that takes them back to the setter. Over time, those rugs can get black and greasy as lane oil makes it way from ball to pins to rug. Calabro, who also serves as his own mechanic, is very meticulous about his old machinery and takes pride in regularly cleaning those rugs.

“I’m doing more preventative maintenance than anyone in the county,” he says. “The rugs ... somewhere else, you reach down and touch it, if feels like asphalt. Nasty. If you’re a bowler, you get a big ol’ black spot on your shirt. Our rugs are done every week. You can bowl here with a white shirt and won’t get a mark on it.”

About those pins ...

Calabro says he replaces all of his bowling pins every two years. Two sets of pins on each of 16 lanes adds up to 320 pins at $14 apiece — nearly $4,500.

As he pulls a new pin from its box, Calabro says, “they’re beautiful pieces of art when new, but boy they get pounded.”

“We sell off the old pins at schools or to anyone who wants them, for about a dollar each. They make great fireplace wood. One match at the bottom, the plastic burns off, and then its solid maple. They will burn for 2 ½ or 3 hours.”

Shoe shopping

Onusko estimates he spends about $500 a month on replacing rental shoes, “just to keep them looking good.”

The most popular sizes are 7 and 8 for women, 9 through 11 for men.

“You try to keep about 20 pairs of each popular size in stock,” he says. “The others, about 10 or 12 pairs.”

The house balls

Eventually, the house bowling ball used by most walk-in bowlers will either develop sharp edges around the finger holes or develop a crack down in its core.

“You can shake it and it’ll rattle,” says Onusko, who says he’ll usually order about two dozen new house balls twice a year, at $17 apiece.

Handicapping

Many bowlers might shy away from league play due to intimidation, but bowling’s handicap system can level the field between, say, someone with a 200 average and someone lucky to break 100.

“I think it’s harder for a 200 bowler to bowl over his average than for a 100 bowler to bowl over his average. That’s how you beat him,” says New Smyrna Lanes manager Juanita Binder. “All leagues are handicap leagues. In my leagues, I have bowlers who have an 89 average all the way up to bowlers with over 200 averages.”