Strangers in a Strange Land: Newport’s Slaves

Newport was the hub of New England’s slave trade, and at its height, slaves made up one-fifth of its population.

Yet little is known about their day-to-day lives.

Ledger documents traced to Caesar Lyndon, a slave for one of the Colony’s early governors, provide one rare glimpse into the private life of an 18th-century slave. But, overall, the slaves left few, if any, journals or diaries to illuminate what they thought or how they felt.

The absence of written material forces historians to rely on tombstones, newspaper accounts, wills, court records and the documents of slave owners and abolitionists to piece together an account of their lives.

* * *

On a cold day in 1768, Pompe Stevens told his brother’s story on a piece of slate. Both men were slaves. A gravestone polisher and carver, Pompe worked for John Stevens Jr., who ran a well-known masonry shop on Thames Street in Newport.

Carefully gouging the stone, Pompe reduced his brother’s life to a single sentence:

This stone was cut by Pompe

Stevens in Memory of his Brother

Cuffe Gibbs, who died Dec. 27th 1768

Little else is known about Gibbs.

The gravestone of Cuffe Gibbs, a slave buried in God’s Little Acre, at the Common Burial Grounds, Newport. The Providence Journal files/Frieda Squires

Experts say he probably came from Ghana, on the west coast of Africa. His surname, Cuffe, is an Anglicized version of Kofi, a traditional name given to Ghanaian boys born on Friday.

But it’s uncertain who owned Gibbs or what he did in Newport, the hub of New England’s slave trade.

More is known about his brother.

Pompe Stevens outlived three wives and eventually won his freedom.

Theresa Guzman Stokes, who wrote a booklet on Newport’s slave cemetery, says Cuffe’s gravestone tells us even more.

Cuffe and Pompe served different masters and lived apart — and Pompe wanted others to understand that they were human, not unfeeling pieces of property, she says.

“He was trying to make it clear. He was saying, ‘This is who I am and this is my brother.’ “

* * *

A gravedigger buried Cuffe Gibbs in the northwest corner of the Common Burying Ground, on a slope reserved for Newport’s slaves,

Already, many headstones dotted the hill.

The 18th century ornate headstone of former slave Pompey Brenton shows the curly hair often seen in depictions of African slaves and decendents within the Common Burying Ground (AP Photo/Victoria Arocho)

Newporters had been importing slaves from the West Indies and Africa since the 1690s. By 1755, a fifth of the population was black. Only two other Colonial cities — New York and Charleston, S.C. — had a greater percentage of slaves.

Twenty years later, a third of the families in Newport would own at least one slave. Traders, captains and merchants would own even more. The wealthy Francis Malbone, a rum distiller, employed 10 slaves; Capt. John Mawdsley owned 20.

On Newport’s noisy waterfront, enslaved Africans cut sails, knotted ropes, shaped barrels, unloaded ships, molded candles and distilled rum. On Thames Street, master grinder Prince Updike — a slave owned by the wealthy trader Aaron Lopez — churned cocoa and sugar into sweet-smelling chocolate.

Elsewhere, Newport’s slaves worked as farmers, hatters, cooks, painters, bakers, barbers and servants. Godfrey Malbone’s slave carried a lantern so that the snuff-loving merchant could find his way home after a midnight dinner of meat and ale.

“Anyone who was a merchant or a craftsman owned a slave,” says Keith Stokes, executive director of the Newport County Chamber of Commerce. “By the mid-18th century, Africans are the entire work force.”

* * *

Some of the earliest slaves were from the sugar plantations in the West Indies where they “seasoned,” developing a resistance to European diseases and learning some English.

Later, slaves were brought directly from slave forts and castles along the African coast. Newporters preferred younger slaves so they could train them in specific trades.

The merchants often sought captives from areas in Africa where tribes already possessed building or husbandry skills that would be useful to their New World owners, Stokes says.

Newly arrived slaves were sometimes held in waterfront pens until they were sold at public auction. Others were sold from private wharves. On June 23, 1761, Capt. Samuel Holmes advertised the sale of “Slaves, just imported from the coast of Africa, consisting of very healthy likely Men, Women, Boys, Girls” at his wharf on Newport harbor.

In the early 1700s, lawyer Augustus Lucas offered buyers a “pre-auction” look at a group of slaves housed in his clapboard home on Division Street.

Many more were sold through private agreements.

The slaves were given nicknames like Peg or Dick, or names from antiquity, like Neptune, Cato or Caesar. Pompe Stevens was named after the Roman general, Pompey the Great.

The John Stevens Shop, c. 1757, where John Stevens, stonecutter, held only one slave. Evidence of the work of the shop indicates that African slave, Pompe Stevens, (aka Zingo Stevens) worked at the shop and produced at least two signed headstones, (one for a fellow slave, and his brother, Cuffe Gibbs) in the late eighteenth century.

* * *

The slaves were thrust into a world of successful merchants like William and Samuel Vernon, who hawked their goods from the docks and stores that rimmed the waterfront. From their store on John Bannister’s wharf, they hawked London Bohea Tea, Irish Linens and Old Barbados Rum “TO BE SOLD VERY CHEAP, For Cash only.”

William and Samuel Vernon made their fortunes in the slave trade and from sales at their store on Bannister’s Wharf. William’s house still stands on Clarke Street in Newport.

On Brenton’s Row, Jacob Richardson offered a “large assortment of goods” from London, including sword blades, knee buckles, pens, Dutch twine, broadcloths, buff-colored breeches, gloves and ribbons.

As property, slaves could be sold as easily as the goods hawked from Newport’s wharves. In December 1762, Capt. Jeb Easton listed the following items for sale: sugar, coffee, indigo — “also four NEGROES.”

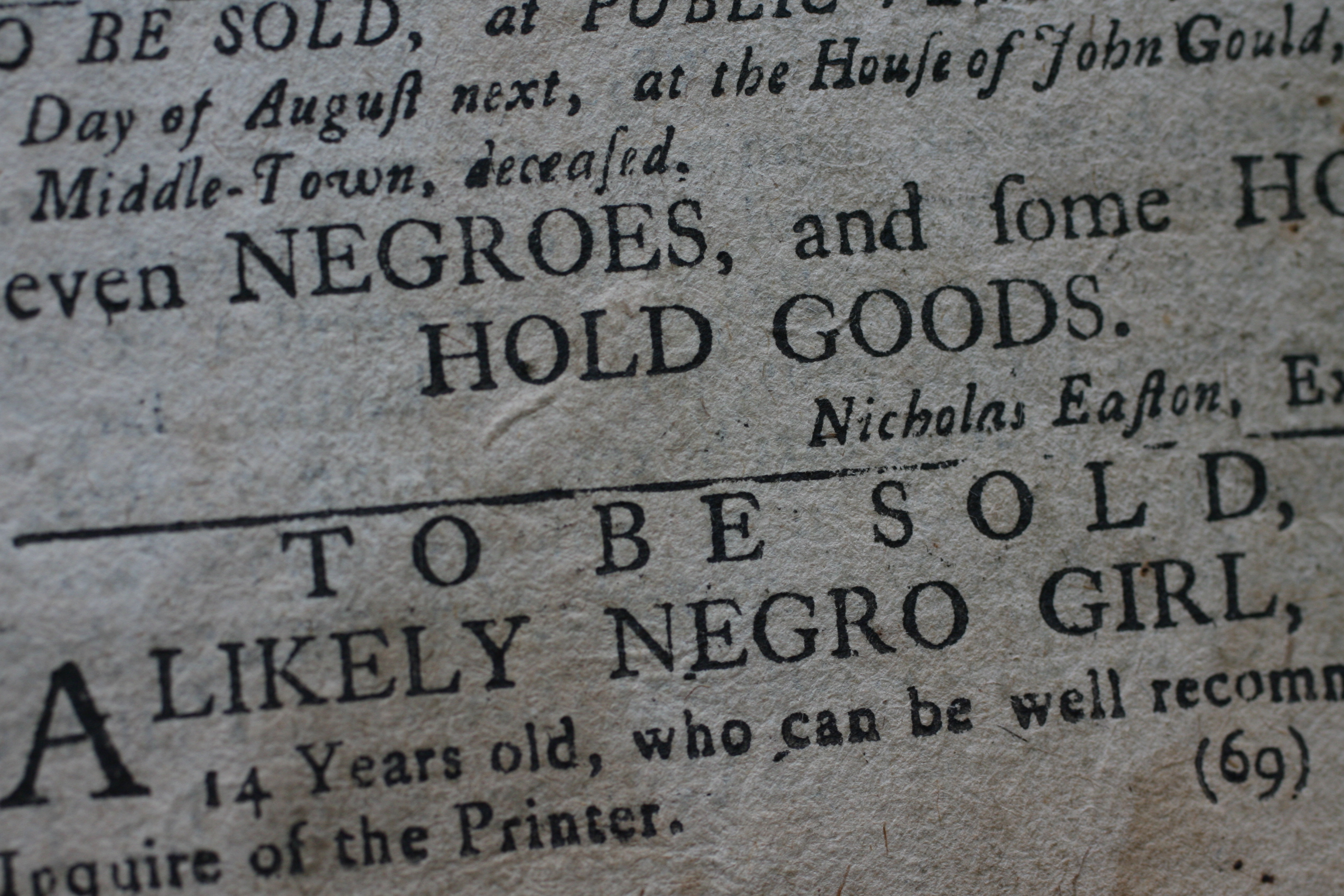

An ad in the Newport Mercury, July 31, 1769, that advertises the sell of negro slaves and household goods.

An icon of a sailing vessel coming into Newport Harbour, from the Newport Mercury, ca. 1758.

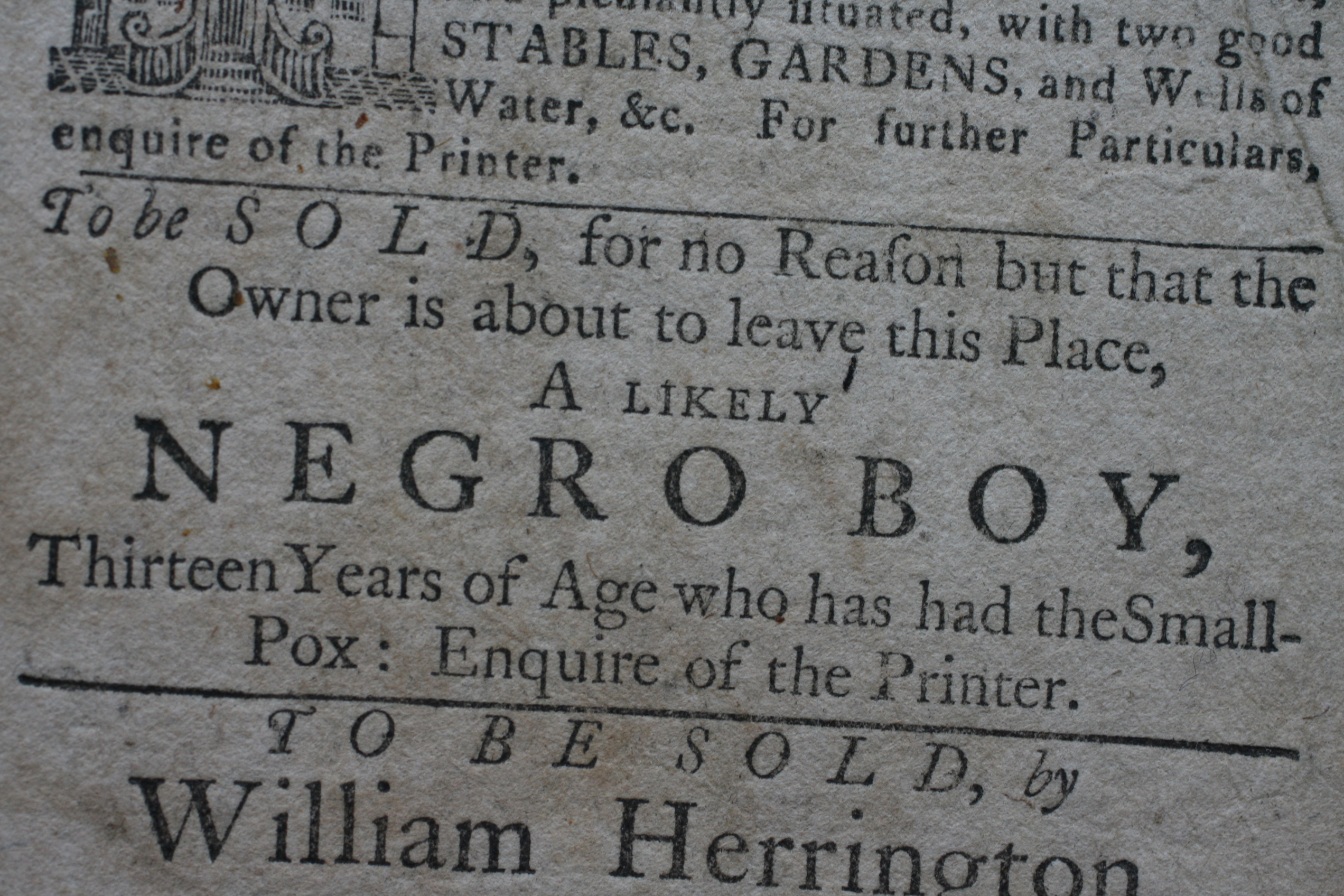

An ad in the Newport Mercury, February 19, 1770, that advertises the sale of a negro boy.

Although Newport was growing — in 1761 the town boasted 888 houses — it was a densely packed community. Most homes, crowded on the land above the harbor, were small.

Slaves slept in the homes of their masters, in attics, kitchens or cellars. In some instances, African children even slept in the same room or bed as their masters.

The opportunity for slaves to establish families or maintain kinship ties was almost impossible in Colonial Newport, says Edward Andrews, a University of New Hampshire history student studying Rhode Island slavery.

His theory is that slaves and servants were discouraged from marrying or starting families to curb urban crowding. Also, some indentured servants had to sign contracts forbidding fornication or matrimony, he says, because Newporters wanted to restrict the growth of the destitute and homeless.

Many slaves had to adopt their master’s religion. Slaves owned by Quakers worshipped at Newport’s Meeting House. Slaves owned by Congregationalists heard sermons from the Rev. Ezra Stiles. The slave Cato Thurston, a dock worker, was a “worthy member of the Baptist Church” who died “in the faith” while under the care of the Rev. Gardner Thurston.

41 Walnut Street, c. 1734, the home of a former African slave, Newport (Neptune) Thurston. Thurston was a cooper by trade, possibly learning the craft from the Baptist minister Gardner Thurston, a cooper by trade and a member of the prominent slave-trading Thurston family.

But even in religion, Africans could only participate partially; most sat in balconies or in the rear of Newport’s churches.

Increasingly restrictive laws were passed to control the slaves’ lives.

Under one early law, slaves could not be out after 9 p.m. unless they had permission from their master. Offenders were imprisoned in a cage and, if their master failed to fetch them, whipped.

Another law, passed in 1750, forbade Newporters to entertain “Indian, Negro, or Mulatto Servants or Slaves” without permission from their masters, and also outlawed the sale of liquor to Indians and slaves. A 1757 law made it illegal for ship masters to transport slaves outside the Colony.

Some fought back by running away. In 1767, a slave named James ran away from the merchants Joseph and William Wanton. It wasn’t unusual.

From 1760 to 1766, slave owners paid for 77 advertisements in the Newport Mercury, offering rewards for runaway slaves and servants.

An image from The Newport Mercury in 1765 describing three enslaved men who ran away.

Unlike the huge plantations in the South, where slaves worked in the hot fields by day and crowded into shacks behind the master’s columned mansion at night, it was different in Newport.

“People sometimes think slaves were better off here because they weren’t picking cotton, but on the other hand, psychologically and socially, they were very much dominated by European life,” says Stokes.

While oppressed, Newport’s slaves still emerged better equipped to understand and navigate the world of their masters.

They learned skills, went to church and became part of the social fabric of the town, achieving a kind of status unknown elsewhere, Stokes says.

“You can’t compare Newport to the antebellum South,” he says. “These are not beasts of the field.”

Theresa Guzman Stokes and Keith W. Stokes, Newport, at God’s Little Acre, the colonial slave burial ground, inside the Common Burying Grounds, Newport. Both the Keith’s lecture on black history.

In fact, many in Newport found ways to forge new lives despite their status as chattel. Some married, earned money, bought their freedom and preserved pieces of their culture.

Caesar Lyndon, an educated slave owned by Gov. Josiah Lyndon, worked as a purchasing agent and secretary. With money he managed to earn on the side, he bought good clothes and belt buckles.

In the summer of 1766, Caesar and several friends, including Pompe Stevens, went on a “pleasant outing” to Portsmouth. Caesar provided a sumptuous feast for the celebrants: a roasted pig, corn, bread, wine, rum, coffee and butter.

Two months later, Caesar married his picnic companion, Sarah Searing, and a year later, Stevens married his date, Phillis Lyndon, another of the governor’s slaves.

Slaves often socialized on Sunday, their day off.

And many slaves worked on trade ships, even some bound for Africa. At sea, they found a new kind of freedom, says Andrews. “They were mobile in a time of immobility.”

Slaves and freed blacks preserved their culture through funeral practices, bright clothing and reviving their African names.

Beginning in the 1750s, Newport’s Africans held their own elections. The ceremony, scholars say, echoed elements of African harvest celebrations.

During the annual event, slaves ran for office, dressed in their best clothes, marched in parades and elected “governors” and other officials.

White masters, who loaned their slaves horses and fine clothes for the event, considered it a coup if their slaves won office.

Historians disagree on the meaning of the elections. Some historians say those elected actually held power over their peers. Others say it was merely ceremonial.

“Election ceremonies are common in all controlled societies,” says James Garman at Salve Regina University. “They act as a release valve. But no matter whose purpose they serve, they don’t address the social inequities.”

* * *

On Aug. 26, 1765, a mob of club-carrying Newporters marched through the streets and burned the homes and gardens of a British lawyer and his friend. A day earlier, merchants William Ellery and Samuel Vernon burned an Englishman in effigy. The Colonists were angry about the English Parliament’s proposed Stamp Act, which would place a tax on Colonial documents, almanacs and newspapers.

Eventually Parliament backed off, and a group of Newporters again hit the streets, this time to celebrate by staging a spectacle in which “Liberty” was rescued from “Lawless Tyranny and Oppression.”

As historian Jill Lepore notes in her recent book on New York slavery, New England’s Colonists championed liberty and condemned slavery. But, in their political rhetoric, slavery meant rule by a despot.

When they talked about freedom, Newport’s elite were not including freedom for the 1,200 African men, women and children who lived and worked in the busy seaport. Many liberty-loving merchants — Ellery and Vernon included — owned or traded slaves.

“I call it the American irony,” says Stokes of the days leading up to the American Revolution. “We’re fighting for political and religious freedom, but we’re still enslaving people.”

Some did not miss the irony.

In January 1768, the Newport Mercury stated, “If Newport has the right to enslave Negroes, then Great Britain has the right to enslave the Colonists.”

By the end of the decade, a handful of Quakers and Congregationalists began to question Newport’s heavy role in the slave trade. The Quakers — often referred to as Friends — asked their members to free their slaves.

And, a few years later, the Rev. Samuel Hopkins, pastor of the First Congregational Church, angered some of his congregation when he started preaching against slavery from the pulpit, calling it unchristian.

Nearby, white school teacher Sarah Osborn provided religious services for slaves.

By 1776, the year the Colonies declared their independence from English rule, more than 100 free blacks lived in Newport. Some moved to Pope Street and other areas on the edge of town, or to Division Street, where white sympathizers like Pastor Hopkins, lived.

In 1784, the General Assembly passed the Negro Emancipation Act, which freed all children of slaves born after March 1, 1784. All slaves born before that date were to remain slaves for life. Even the emancipated children did not get freedom immediately. Girls remained slaves until they turned 18; boys were slaves until they were 21.

The Rev. Samuel Hopkins, D.D. Credit: The Newport Historical Society.

That same year, Pastor Hopkins told a Providence Quaker that Newport “is the most guilty respecting the slave trade, of any on the continent.” The town, he said, was built “by the blood of the poor Africans; and that the only way to escape the effects of divine displeasure, is to be sensible of the sin, repent, and reform.”

After the American Revolution, Newport’s free blacks formed their own religious organizations, including the African Union Society, the nation’s first self-help group for African-Americans.

Pompe Stevens was among them.

No longer a slave, he embraced his African name, Zingo.

The society helped members pay for burials and other items, and considered various plans to return to Africa. In time, other groups formed, including Newport’s Free African Union Society.

In 1789, the society’s president, Anthony Taylor, described Newport’s black residents as “strangers and outcasts in a strange land, attended with many disadvantages and evils? which are like to continue on us and on our children while we and they live in this Country.”

Paul Davis is a former staff writer for The Providence Journal.