Plantations in the North: The Narragansett Planters

While Newport merchants profited by trafficking in slaves, colonists across the Narragansett Bay found another way to grow rich.

They used slaves to grow crops and raise livestock on small plantations throughout South County.

For 50 years, Newport’s merchants loaded the surplus farm products onto ships bound for slave plantations in the West Indies where they were traded mostly for sugar and molasses.

By 1730, the southern part of Rhode Island was one-third black, nearly all of them slaves.

The Narragansett Planters thrived from the early 1700s to just before the American Revolution, which brought trade to a standstill.

* * *

From his counting house above Newport harbor, Aaron Lopez fretted about the future.

The Portuguese immigrant had sold soap in New York, candles in Philadelphia and whale oil in Boston. But a plan to trade goods with England failed because the market was glutted. Now, heavily in debt to an English creditor, Lopez sought a new market.

Sarah Rivera Lopez and son, Joshua, c 1775 by Gilbert Stuart, oil on canvas, The Detroit Institute of Fine Arts

He chose Capt. Benjamin Wright, a savvy New England trader, as his agent in Jamaica. From the tropics, Wright acted as a middleman between Lopez and his new buyers — slave owners too busy making sugar to grow their own food.

Don’t worry, Wright told Lopez in 1768. “Yankey Dodle will do verry well here.”

Yankee Doodle did.

His chief suppliers were just across the Bay.

There, amid the rolling hills and fertile fields, hundreds of enslaved Africans worked for a group of wealthy farmers in South Kingstown, North Kingstown, Narragansett, Westerly, Exeter and Charlestown.

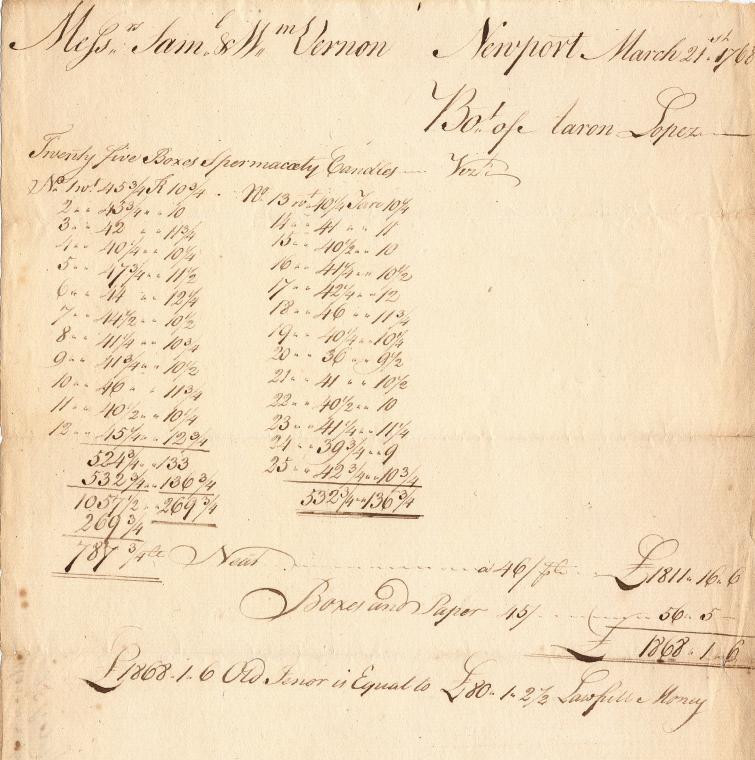

Invoice from Aaron Lopez to Samuel and William Vernon. New York Public Library

Relying on slave labor, the so-called Narragansett Planters raised livestock and produced surplus crops and cheese for Newport’s growing sea trade.

The slaves, brought by Newport merchants from the West Indies and later Africa, cut wheat, picked peas, milked cows, husked corn, cleaned homes and built the waist-high walls that bisected the fields and hemmed them in.

So many blacks worked along the coast that, by the mid-1700s, southern Rhode Island boasted the densest slave population in New England, along side Boston and Newport.

While most New England communities were organized in compact villages with small farms, southern Rhode Island evolved into a plantation society.

“South County was unique in New England,” says author Christian M. McBurney.

Cheap land made it possible, he says.

The Narragansett Indians had once ruled the region, but Colonial wars and disease had greatly reduced their number, leaving huge tracts of vacant land up for grabs. A territory dispute between Connecticut and Rhode Island scared off some timid settlers.

Investors, many of them from Newport and Portsmouth, “scrambled to the top,” says McBurney. They bought land on credit, sold the unwanted lots to generate cash and started farms.

By 1730, the most successful planters – including the Robinson, Hazard, Gardner, Potter, Niles, Watson, Perry, Brown and Babcock families — owned thousands of acres. In Westerly, Col. Joseph Stanton owned a 5,760-acre estate that stretched more than four miles long.

A typical farm had 300 sheep, 100 bulls and cows and 20 horses.

“The most considerable farms are in the Narragansett country,” concluded William Douglas who, in 1753, surveyed the English settlements in North America for the Mother Country. The region’s rich grazing and farm lands benefited from warm winters and “a sea vapour which fertilizeth the soil,” he wrote.

The owners sometimes relied on family members and indentured Indians for help, but slaves did most of the work. The largest planters — families like the Robinsons, Updikes and Hazards — owned between 5 and 20 slaves.

The Hazard House, circa 1740, on Old Boston Neck Road, Narragansett. Land was purchased from the Narragansett Indians by Humphrey Atherton, in 1661. The house was built about 1740 by George Hazard the great-grandfather of Mr. Thomas G. Hazard.

Although their plantations were much smaller than those in the southern Colonies, an early historian described the area as “a bit of Virginia set down in New England.”

Made rich from their exports, the planters built big homes, sent their children to private schools and carved the hillsides into apple orchards and gardens.

North Kingstown planter Daniel Updike kept peacocks on his 3,000-acre farm. Framed by deep blue feathers, the exotic peafowl screeched and strutted in their New World home.

* * *

Rowland Robinson, a third-generation planter and slave holder, was one of the region’s most successful planters.

In 1700, his grandfather purchased 700 acres on Boston Neck, “east by the salt water.” By the time he died, the elder Robinson owned 629 sheep, 131 cows and bulls, 64 horses and eight slaves.

The Hannah Robinson House, on Old Boston Neck Road, Saunderstown, built in 1710 by Rowland Robinson, a wealthy Narragansett planter.

His son, William, the Colony’s lieutenant governor, increased the family fortune by acquiring more land. William, who owned 19 slaves, died in 1751, and Rowland, one of six sons, settled on the family estate.

Tall and handsome, with “an imperious carriage,” the younger Robinson rode a black horse and owned more than 1,000 acres and a private wharf. His farm, a mile from the Bay, gave him easy access to the Newport market. During a two-year period in the 1760s, he delivered more than 6,000 pounds of cheese, 100 sheep, 72 bundles of hay, 51 bushels of oats, 30 horses and 10 barrels of skim milk to Aaron Lopez, who then shipped them to the West Indies and other markets.

Most planters relied on public ferries. They hauled their cheese, beef, sheep and grains along muddy Post Road to South Ferry, the public port that was a vital link between Newport and the Narragansett country, also called King’s County.

In 1748, Boston Neck planter John Gardiner urged legislators to expand the busy port at South Ferry. The current boats, he complained, are “crowded with men, women, children” along with “horses, hogs, sheep and cattle to the intolerable inconvenience, annoyance and delay of men and business.”

* * *

According to one account, Rowland Robinson owned 28 slaves. Tradition says he abandoned the slave trade after a boatload of dejected Africans arrived at his dock.

But the region’s planters bought slaves until the American Revolution.

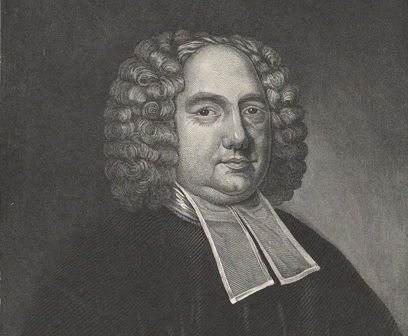

Even small farmers, like the Rev. James MacSparran, owned field hands and domestic servants. “My two Negroes are threshing rye,” wrote MacSparran, who owned 100 acres, on July 29, 1751.

Rev. James MacSparran. Image Provided by the New York Public Library

Their work had a profound effect on the economy, says historian Joanne Pope Melish.

Freed from domestic chores, white masters were able to pursue other opportunities, jobs or training. Some learned new trades, became lawyers or judges, or sought public office.

In the end, slave labor helped Rhode Island move from a household-based economy to a market-based economy, says Melish. “Slaves contributed to the expansion and diversification of the New England economy,” she says.

Plantation owners, merchants, importers and retailers prospered on both sides of the Bay.

From his home on Thames Street, Aaron Lopez could walk to his private pier and a warehouse next to the town wharf. In a loft above his office, sail makers stitched sheets of canvas. His Thames Street shop supplied Newport’s residents with everything from Bibles and bottled beer to looking glasses and violins.

Lopez, one of the founders of Touro Synagouge, and his father-in-law, Jacob Rivera, owned more than a dozen slaves between them, and sometimes rented them to other merchants.

Lopez became Newport’s top taxpayer. He owned or had interest in 30 ships, which sailed to a dozen ports, including Africa.

He wasn’t alone. By 1772, nearly half of Newport’s richest residents had an interest in the slave trade.

“The stratification of wealth was astonishing,” says James Garman, a professor at Salve Regina University. “And it had everything to do with the African trade.”

Although the Narragansett Planters weren’t as well off as their monied counterparts across the Bay, they took their cues from Newport’s merchants and the English gentry.

Their large houses — Hopewell Lodge in Kingston, and Fodderring Place at Point Judith — often stood more than a mile apart.

The John Potter house in Matunuck has seven fireplaces including this one in a parlor next to an arched alcove china nook. The Providence Journal/Sandor Bodo

John Potter’s “Greate House” in Matunuck included elegant woodwork and a carved open arch. Rowland Robinson’s house featured gouged flower designs, classical pilasters and built-in cupboards adorned with the heads of cherubs.

Reverend MacSparran described a typical day of socializing: “I visited George Hazard’s wife, crossed ye Narrow River, went to see Sister Robinson, called at Esq. Mumford’s, got home by moon light and found Billy Gibbs here.” So much company, he confessed, “fatigues me.”

Their wealth “brought social pretensions and political influence all without parallel in rural Rhode Island and New England,” says McBurney.

The elegant lifestyle did not last.

During the Revolutionary War, the British burned Newport’s waterfront. Many merchants fled, and trade stalled. Lopez moved to Leicester, Mass. In 1782, he drowned when his horse plunged into a pond.

The Narragansett Planters did not recover from the loss of the Newport market. The sons of the big planters chopped the plantations into small farms. Some freed their slaves.

But before the Revolution, they lived a carefree life.

In the spring, they traveled to Hartford to “luxuriate on bloated salmon.” In the summer, they raced horses on the beach and roasted shellfish, says Wilkins Updike in a history of the Episcopal Church in Narragansett.

During corn-husking festivals, men and women gathered for “expensive entertainments” in the large halls of “spacious mansions,” says Updike.

The men wore silk stockings, shoes with shiny buckles and “scarlet coats and swords, with laced ruffles over their hands.” Their hair was “turned back from the forehead and curled and frizzled” and “highly powdered.”

The women, dressed in brocade and high-heeled shoes, “performed the formal minuet with its thirty-six different positions and changes. These festivities would sometimes continue for days.Ö These seasons of hilarity and festivity were as gratifying to the slaves as to their masters,” Updike says.

In the 18th century, Yankee Doodle did all right.

On the farms and on the wharfs he made money — sometimes as a slave owner, sometimes as a slave trader, sometimes as both.

Paul Davis is a former staff writer for The Providence Journal.