Living Off the Trade: Bristol and the DeWolfs

Rhode Island outlawed slave trading in 1787, but it didn’t stop the trafficking.

Almost half of all of Rhode Island’s slave voyages occurred after trading was outlawed. By the end of the 18th century, Bristol surpassed Newport as the busiest slave port in Rhode Island.

In 1807, the United States Congress, after a bitter debate, banished the slave trade and Rhode Island’s 75-year reign sputtered to an end.

Rhode Island’s rum mills were gradually replaced by cotton mills. Bristol was broke, Newport was struggling and Providence merchants turned to manufacturing.

* * *

Samuel Bosworth was scared. He was ordered to buy a ship at auction to keep it out of the hands of its owner, Charles DeWolf, one of Bristol’s biggest slave traders.

Federal officials had just seized the Lucy, which they were sure DeWolf planned to send to Africa on a slave voyage — a clear violation of a 1794 law that prohibited Americans from fitting out vessels “for the purpose of carrying on any trade or traffic in slaves, to any foreign country.”

U.S. Treasury officials wanted to send a message to Rhode Island’s slavers so they instructed Bosworth, a government port surveyor, to outbid competitors. In the past, slave traders caught violating the law simply repurchased their ships at auction, often at a fraction of their value.

Keeping the Lucy from DeWolf would not be popular.

Charles and his brothers had prospered from trafficking in human cargo since the 1780s and the town’s residents depended on them for their livelihood. Bristol’s craftsmen made iron chains, sails and rope for the slave ships; farmers grew onions and distillers made rum — all items needed to support the trade.

The night before the auction, three of Rhode Island’s wealthiest men appeared at Bosworth’s home. Charles and James DeWolf and John Brown, a Providence merchant who had just been elected to Congress, warned Bosworth not to go, saying it was not part of his job as a surveyor. But Bosworth had little choice.

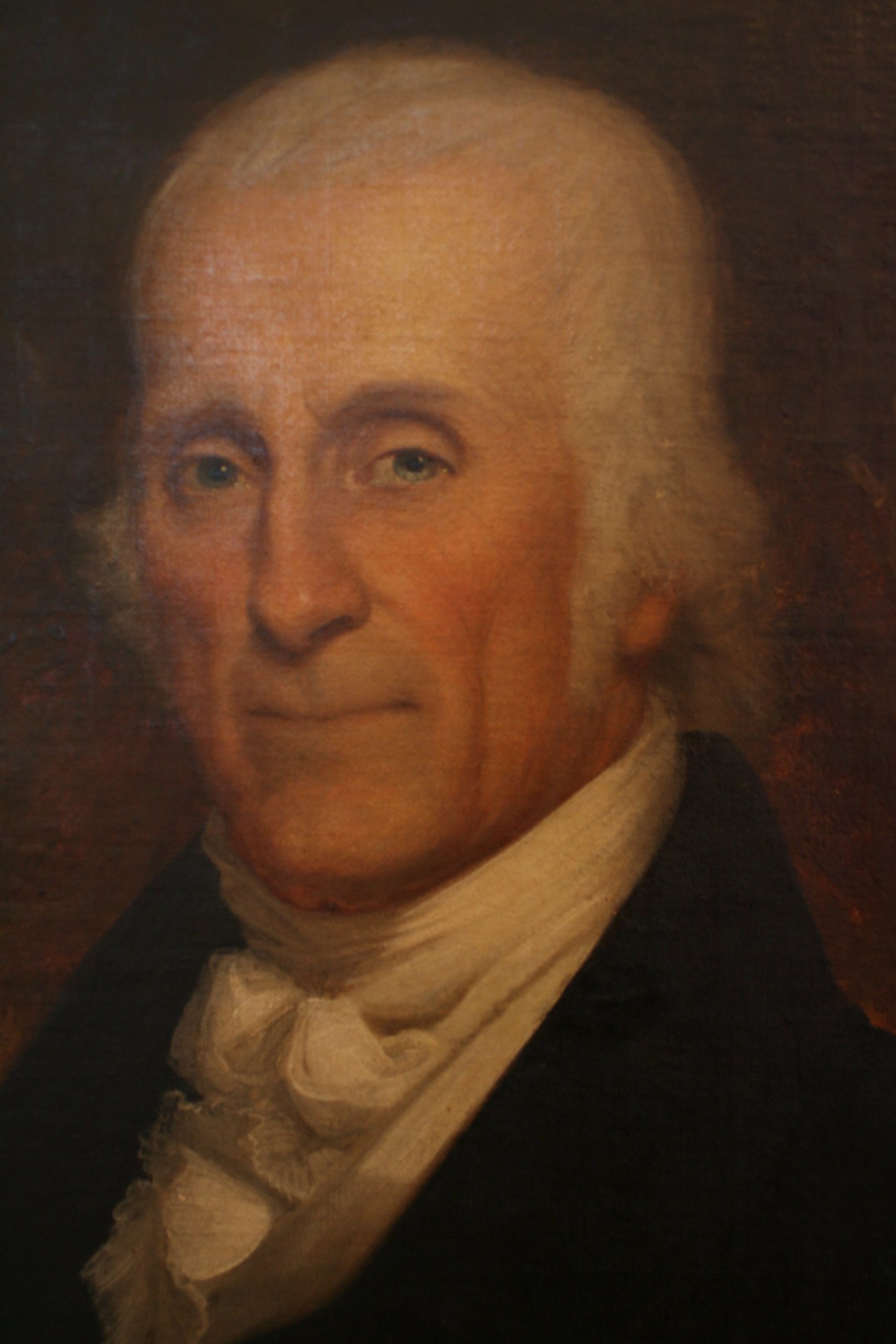

This portrait of Charles DeWolf, hangs in the Bristol Preservation and Historical Society. The painting is from an original painting by Jarvis in the possession of Col. S.P. Colt.

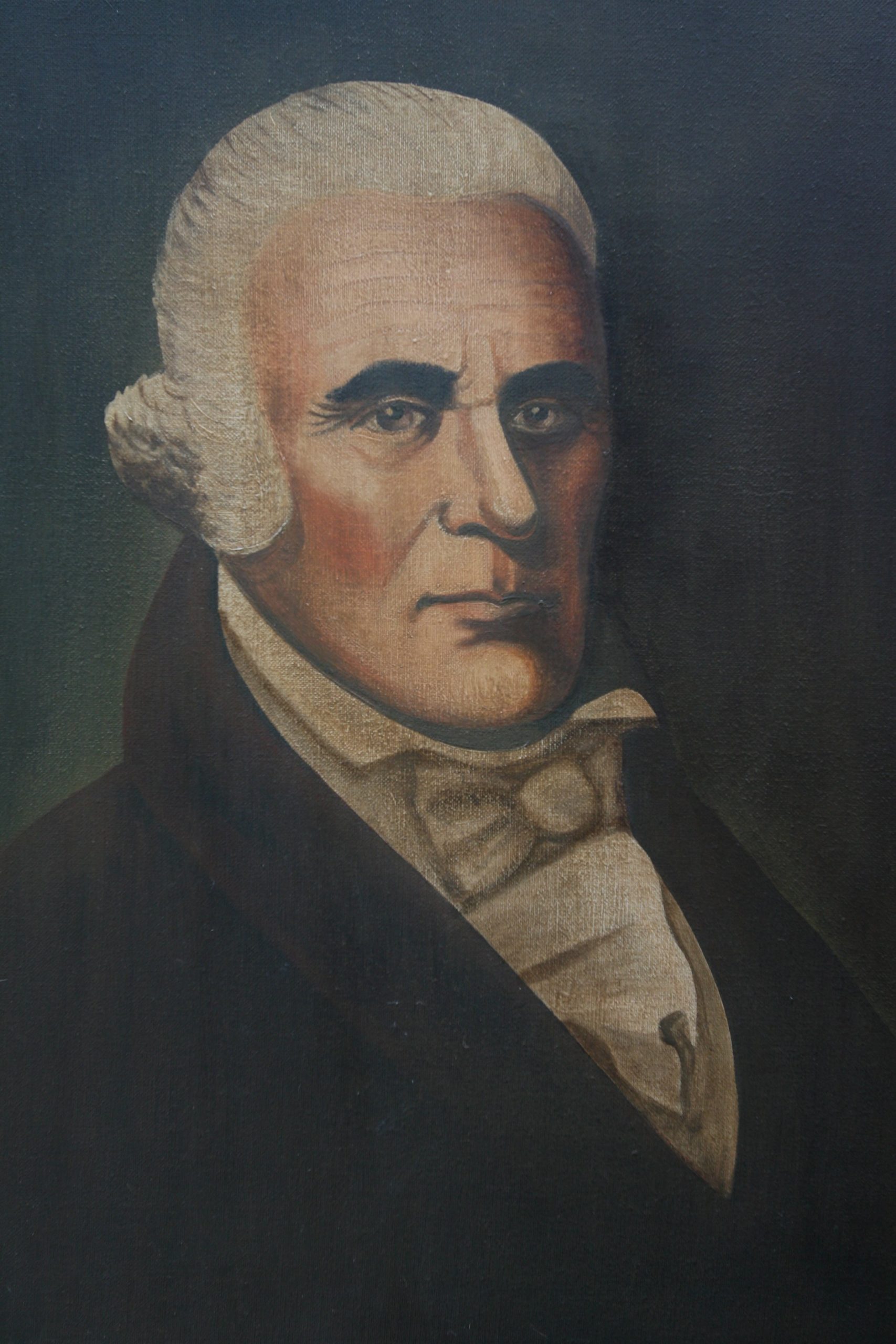

A painting of James DeWolf, recently done for the new DeWolf Tavern, located on the waterfront in Bristol.

Portrait of John Brown by Edward Malbone. New York Historical Society. Photo by John Hartey.

He had been pressured by William Ellery, Newport’s zealous customs collector, a “straight-gazing patriot” who had signed the Declaration of Independence 23 years earlier. Although his father had been a slave trader, Ellery regarded smuggling slaves as “nothing short of treason,” writes George Howe, a DeWolf descendant.

On the morning of the auction, July 25, 1799, Charles DeWolf approached Bosworth a second time. If he tried to buy the Lucy, he would likely be “insulted if not thrown off the wharf by some of the sailors,” DeWolf warned.

Bosworth continued on his way. But he never reached the town wharf.

As he neared the Lucy, eight men in Indian garb and painted faces grabbed him and pushed him into a sailboat. The black-faced men sailed Bosworth around Ferry Point and dumped him at the foot of Mount Hope, two miles from the auction site.

With Bosworth out of the way, a DeWolf captain bought the Lucy for $738.

“The government had found the slave traders more than a match on their home turf, and never tried the tactic again,” says historian Jay Coughtry.

The DeWolfs were just getting started.

* * *

Already, the clan owned a piece of Bristol’s waterfront.

The brothers William and James DeWolf operated from a wharf and a three-story brick counting house on Thames Street, overlooking the harbor.

The renovated DeWolf Tavern, now a restaurant in Bristol. The DeWolfs used this building, built from stones used for ballast on ships coming from Africa, as a warehouse.

At the turn of the century, the family founded the Bank of Bristol, chartered with $50,000 in capital. Among the chief stockholders in 1803 were two generations of DeWolfs — John, Charles, James, William, George and Levi.

The clan also started the Mount-Hope Insurance Co., which insured their own slave ships.

Business was good.

Before the American Revolution, Newport merchants dominated the slave trade. But from 1789 to 1793, nearly a third of Rhode Island’s slave ships sailed from Bristol. By 1800, Bristol surpassed Newport as the busiest slave port.

The DeWolfs financed 88 slaving voyages from 1784 to 1807 – roughly a quarter of all Rhode Island slave trips during that period. Alone, or with other investors, the family was responsible for nearly 60 percent of all African voyages that began in Bristol.

“This will inform you of my arrival in this port safe, with seventy-eight well slaves,” wrote Jeremiah Diman to James DeWolf on April 1, 1796. Writing from St. Thomas, Diman said he’d lost two slaves on the voyage from Africa, and promised to leave soon for Havana to sell the others. “I shall do the best I can, and without other orders, load with molasses and return to Bristol.”

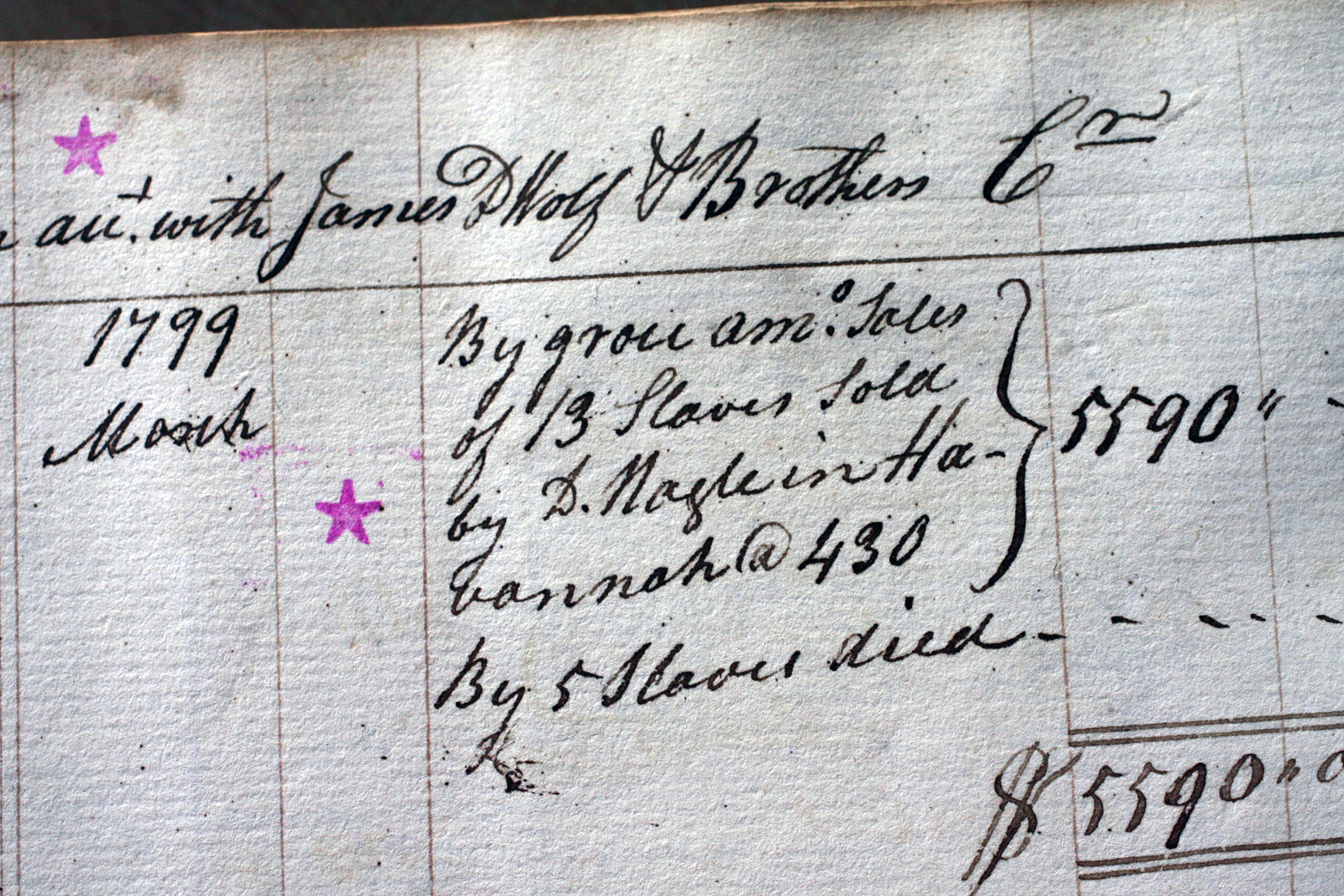

A waterfront store ledger at the Bristol Historical Society details the sale of 13 slaves in “Havannah“ by James DeWolf. [The Providence Journal, file / Frieda Squires]

The DeWolfs owned five plantations in Cuba — among them the Mary Ann, the New Hope and the Esperenza — where their slaves grew sugar cane and coffee.

The DeWolfs also brought some slaves back to Bristol, where they were “sold to some of the best families in the state,” says historian Charles O.F. Thompson.

In 1803, James DeWolf gave his wife an African boy and girl for Christmas.

* * *

They were self-made men.

Too poor to stay in school, they took jobs on ships.

Their father, Mark Anthony DeWolf, was a slaver and a seaman, too. But he never made any money from it.

He married the daughter of wealthy privateer Simeon Potter, moved from Guadaloupe to Bristol and sailed on Potter’s ships. After years of scrambling to make a living, he died, broke, of a “nervous fever” in 1793.

Between voyages he sired 15 children. Three of his sons died at sea. But five — James, John, Charles, William and Levi — survived. The “Quakerish” Levi quit the slave trade after a single voyage, but the others prospered from the trade, privateering, whaling and other ventures.

Each son worked a different part of the family business. Charles, the oldest, acted as the family’s financial consultant.

William ran the Mount-Hope Insurance Company, which insured ships and their cargoes against “the dangers of the seas, of fire, enemies, pirates, assailing thieves, restraints and detainments of kings . . . and all other losses and misfortunes.” Ships and their cargoes were insured at up to $7,000.

In 1804, Henry DeWolf moved to South Carolina to handle the family’s slave sales in Charleston. The move was typical; the family placed relatives or in-laws in every part of their slaving enterprise from Bristol to Cuba.

At the urging of the DeWolfs, Congressman John Brown helped establish Bristol and Warren as a separate customs district where slave traders could operate away from “the prying eyes” of William Ellery in Newport, says Coughtry. A few years later, the family successfully lobbied President Thomas Jefferson to name Charles Collins, a slave trader and DeWolf cousin, as head of the new district.

Collins had been captain of the seized ship, the Lucy.

The family’s hold was now complete.

From 1804 to 1807, the prosecution of slave traders ceased, and the number of Africa-bound ships from Bristol soared.

“The DeWolf family monopolized the slave trade,” says Kevin E. Jordan, a retired professor at Roger Williams University.

To keep an eye on their trade, the DeWolfs built huge homes near the harbor.

Charles hired ship carpenters to build the Mansion House on Thames Street before 1785. It had four entrances, with broad halls running north to south and east to west. Wallpaper in the drawing room featured exotic birds with brilliant plumage.

Two decades later, James hired architect Russell Warren to build The Mount, a white three-story home with five chimneys, a deer park and a glass-enclosed cupola. Each day, his wife’s slave washed the teak floors with tea leaves.

In 1810, George hired Warren to design a $60,000 mansion with fluted Corinthian columns, a three-story spiral staircase and a skylight. The estate is now referred to as Linden Place.

Linden Place, the family home of the DeWolfs, is ornamented with bronze figuative sculpture. The Providence Journal/Sandor Bodo

* * *

James DeWolf was the most extraordinary of the brothers. His life, says historian Wilfred H. Munro, resembled “the wildest chapters of a romance.”

Born in Bristol in 1764, he boarded Revolutionary War ships as a boy, and was held prisoner by the British in Bermuda. The cruelty and hardship he experienced as a young prisoner “made him a man of force and indomitable energy with no nice ethical distinctions,” says one biographer.

In his early 20s, he sailed aboard the slave ship Providence, owned by John Brown; he bought his own slave ship, a 40-ton schooner, in 1788.

Tall, with gray-blue eyes, he had big sailor’s hands — and a Midas touch, says Munro.

While his fellow merchants “were cautiously weighing the possible chances of success in ventures in untried fields, he was accustomed to rush boldly in, sweep away the rich prizes that so often await a pioneer, and leave for those who followed him only the moderate gains that ordinary business affords,” writes Munro.

Some called his boldness cruel.

In 1791, a grand jury charged James with murdering a slave aboard a bark the year before. The woman, who had smallpox, had to be jettisoned before she contaminated the other slaves and crew, some sailors testified in his defense.

But jurors said the slave ship captain did not have “the fear of God before his eyes.” Instead, he was “moved and seduced by the instigation of the Devil” when he threw the woman from his ship. She “instantly sank, drowned and died . . . ” the jury said.

Although an arrest warrant was issued, the federal marshal from Newport reported twice annually that he couldn’t find James. After four years, the charge was dropped. Whether James was in Bristol during these years or, as one historian writes, hiding out in the Danish West Indies, is unclear.

It wasn’t the only time James flouted the law. After it became illegal to sell slaves in foreign lands, he and his captains disguised their mission by equipping their ships with slave quarters after they left Rhode Island waters. Others simply sailed past Newport in the dark.

Before he turned 25, James had accumulated considerable wealth. His 1790 marriage to Nancy, the daughter of Deputy Gov. William Bradford, brought him more money. During the War of 1812, he sent out his own 18-gun brig with the government’s blessing and captured 40 British vessels worth more than $5 million, says Ray Battcher III, curator of the Bristol Historical & Preservation Society.

He emerged, according to Battcher, as one of the richest men in the United States.

When the federal government ran low on credit, James DeWolf loaned the nation money.

He built the Arkwright Mills in Coventry, where workers made cloth from cotton grown by southern slaves. He also converted some of his ships into whalers, took up farming and traded with China.

In his late 30s, he entered politics. In 1802, he won a seat in the state legislature and later became speaker of the House. Locally, he was town moderator. In 1821, he went to Washington to serve in the Senate.

DeWolf’s reputation as a slave trader followed him.

During a Senate debate over whether Missouri should be admitted as a slave state, a senator from South Carolina noted that some Rhode Islanders opposed the move and were bitter toward slaveholders.

But such a sentiment could not be widespread, he said with sarcasm.

After all, Rhode Island voters elected James DeWolf to represent them — a man who “had accumulated an immense fortune by the slave trade.”

The southern senator noted that of the 202 vessels that carried slaves to South Carolina from 1804 to 1807, 59 were from Rhode Island — and 10 belonged to DeWolf. DeWolf left the Senate before his term was up — one biographer said he was bored.

When slave merchant James DeWolf traveled to Washington as a senator, he rode in the ornate carriage that is kept at Linden Place, in Bristol, the George DeWolf family mansion.

The family crest that is painted on the door of the carriage.

* * *

After 1807, a much stronger federal law ending the slave trade was passed, and the DeWolfs’ hold on Bristol began to unravel. They moved their slaving operation to their Cuban plantations.

In 1825, when George DeWolf’s sugar cane crop failed, he defaulted on a business bank loan, bringing three banks to near collapse. The reverberations hit the other DeWolfs and much of Bristol. “The family went bankrupt. They couldn’t pay the farmers” or other suppliers “so the people all went bankrupt,” says Jordan.

Among them was slave ship Capt. Isaac Manchester, who lost $80,000 and turned to clamming to earn a living.

According to one account, women wept and even churches closed their doors.

“General DeWolf has failed utterly!” wrote Joel Mann to his father on Dec. 12, 1825.

“All night and yesterday officers and men were flying in all directions, attacking and securing property of every description. All classes of men, even clergymen and servants, are sufferers. Many among us are stripped of everything. Honest merchants and shopkeepers have lost all or nearly all,” the pastor of the Bristol Congregational Church wrote.

“The banks are in equal distress. A director has just told me that the General is on paper in some way or other at all the banks . . . The Union Bank is thought to be ruined — perhaps others.”

Six months later, the directors of the Bristol Union Bank, Eagle Bank and Bank of Bristol asked the General Assembly for tax relief because DeWolf’s failure had cost them more than $130,000 in capital.

James lost money, too, but died, in 1837, a millionaire. His estate included property in Ohio, Kentucky, Maryland, New York and Bristol.

To avoid Bristol’s creditors, George DeWolf left his Bristol mansion at night, just before Christmas. Eight years earlier, he had entertained President James Monroe there.

“All the creditors stormed the place and looted it,” says Jordan. “They pulled out everything that wasn’t nailed to the walls. They took the chandeliers from the ceilings.”

Paul Davis is a former staff writer for The Providence Journal.