1 Boye Slave Dyed: The Terrible Voyage of the Sally

The first ship to leave Providence for Africa was sent by James Brown in 1735, but only a smattering of ships departed from that port before the Revolutionary War.

Providence never became a busy slave center, like Newport and Bristol.

Newport dominated the state’s slave trade for the first 50 years. All trade came to a halt during the seven years the colonies fought for independence from Great Britain. When the war ended, Rhode Island ships again headed for Africa.

Newport continued to send dozens of ships to Africa, but Providence and Warren, and especially Bristol, became bigger players.

Between 1784 and 1807, 402 ships sailed from Rhode Island for Africa. Providence, which sent 55 of those ships, accounted for only 14 percent of the state’s slave trade.

* * *

Capt. Esek Hopkins had just cleared the African coast when one of his captives died.

The young girl wasn’t the first.

For nine long months, Hopkins had bartered with slave traders on behalf of the Brown brothers of Providence — Nicholas, Joseph, John and Moses. By late August 1765, he had finally purchased enough slaves, 167, so he could leave. Tarrying on the malarial coast — sailors called it the White Man’s Grave — Hopkins had already lost 20 slaves and 2 members of his crew.

Now, on board the 120-ton brig Sally, the deaths continued.

1 boye slave Dyed, Hopkins wrote on Aug. 25. He kept a tally of the slave deaths in his trade book. The young boy was number 22.

The Browns had instructed Hopkins to sell his slaves in the West Indies for “hard cash” or “good bills of exchange.”

“Dispatch,” they reminded him, “is the life of Business.”

Esek Hopkins, 46, had spent years at sea, but, until now, he had never helmed a slave ship.

At 20, he left the family farm in Scituate to board a ship bound for Surinam, a South American port favored by Newport captains and slave dealers. Two older brothers also sailed. John died at sea; Samuel died at Hispaniola, a Caribbean slave and sugar center, now known as Haiti and the Dominican Republic.

Stephen, a third brother, rose through the ranks of Colonial politics and became governor of Rhode Island.

Esek married in 1741, bought a farm in Providence and also dabbled in civic affairs. But he preferred the sea. Aggressive and outspoken, he worked for more than three decades as a privateer and merchant-adventurer, sometimes for the Browns. During the Seven Years’ War between England and France, he captured a French ship loaded with oil and other goods.

But commanding a slave ship required knowledge of African tribal customs and negotiating skills; he possessed neither. He wasn’t even the Browns’ first choice; many Rhode Island captains were already on the African coast.

* * *

Stocked with handcuffs, leg irons, chains and padlocks, the Sally was a floating prison.

The women, mostly naked, lived unchained on the quarterdeck. Crew members believed there was little chance they would stage a rebellion.

The males, chained together in pairs, were kept below deck, where they struggled for air in the dark humid hold. Their spaces were so cramped they struggled to sit up.

In good weather, Hopkins and his crew exercised the more than 100 African slaves on deck, and scrubbed their filthy quarters with water and vinegar.

On Aug. 28, just eight days after leaving the coast of Africa, Hopkins freed some of the slaves to help with the chores. Instead, they freed other slaves and turned on what was left of his crew.” . . . the whole rose upon the People, and endeavored to get Possession of the vessel,” the Newport Mercury reported later.

Outnumbered, the sailors grabbed some of the weapons aboard the Sally: 4 pistols, 7 swivel guns, 13 cutlasses, 2 blunderbusses and a keg of gunpowder. The curved cutlass blades and short-barreled blunderbusses — favored by pirates and highwaymen — were ideal weapons for killing enemies in close quarters.

“Destroyed 8 and several more wounded,” Hopkins wrote. One slave suffered broken ribs, another a cracked thigh bone. Both later died.

At sea, the Sally creaked and rolled as the crew kept careful watch on the remaining males shackled on the decks below.

Above deck, Hopkins revised the death count in his trade book.

32, he wrote.

* * *

Back in Providence, the Browns had high hopes for the Sally.

Among the city’s richest men, they operated under the name Nicholas Brown and Company. They owned all or partial interest in a number of ships; a candle factory at Fox Point; a rope factory, sugar house and chocolate mill and two rum distilleries.

Just before the Sally sailed, they invested in an iron foundry on the Pawtuxet River, the Hope Furnace in Scituate. Esek’s brother, Stephen, was a partner.

To help raise cash for the new foundry and their candle business, the Browns invested in the Sally and two non-slave ships that carried horses and other goods to the Caribbean.

Sending the Sally to Africa marked the first time the four brothers, as a group, had ventured into the slave trade.

Their great-great grandfather, Chad Brown, had been an early religious leader of the colony along with founder Roger Williams. The brothers’ grandfather, James, a pious Baptist church elder, was openly critical of Providence’s rising merchant class.

Yet, his son, Capt. James Brown, rejected the pulpit for the counting house. He sailed to the West Indies, ran a slaughter house, opened a shop and ran two distilleries. Unlike the earlier Browns, James recorded his children’s births in his business ledger, rather than the family Bible.

And in 1735, he sent Providence’s first slave ship to Africa.

“Gett Molases if you can” and “leave no debts behind,” James wrote to his brother, Obadiah. The market was poor; still, Obadiah traded the Mary’s human cargo in the West Indies for coffee, cordage, duck and salt. He brought three slaves, valued at 120 English pounds, back to Providence.

When James died three years later, Obadiah helped raise his brother’s sons: Nicholas, Joseph, John and Moses.

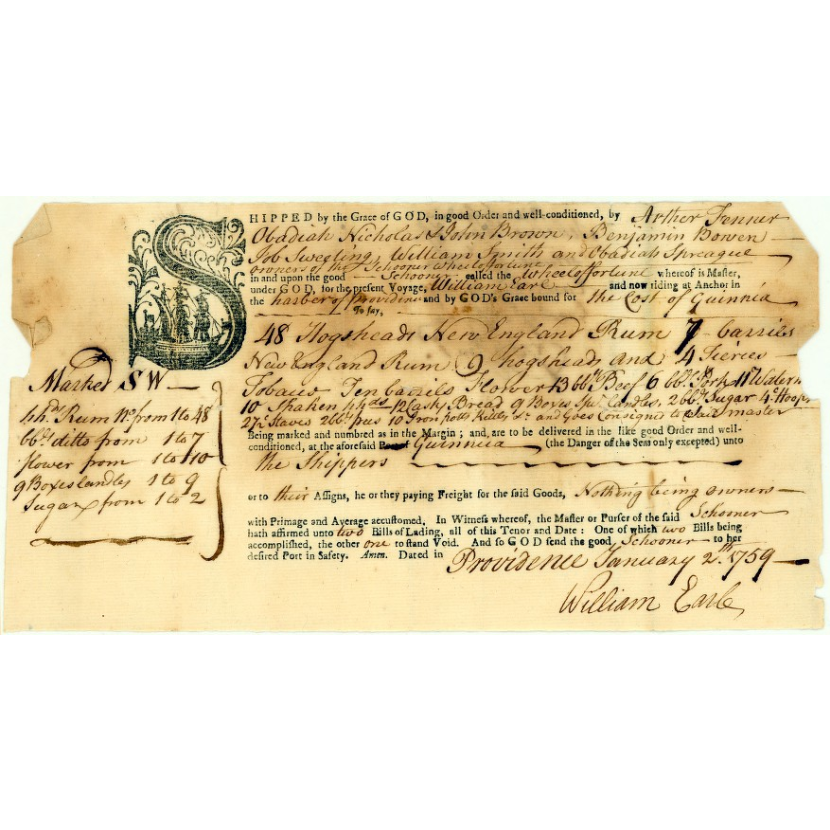

In 1759, John and Nicholas joined Obadiah and other merchants in outfitting another slave ship, the Wheel of Fortune. It was captured by a French privateer. “Taken” wrote Obadiah in his insurance book.

“Manifest of the Wheel: January 2, 1759 ” (1759). Voyage of the Sally, Steering Committee on Slavery and Justice. Brown Digital Repository. Brown University Library.

The sons were not deterred.

Although the local economy had suffered during the war between France and Britain, the slave trade surged in 1763.

In Virginia, plantation owner Carter Braxton urged the Browns to send him slaves. I understand, he said, there is a “great Traid carried on from Rhode Island to Guinea for Negroes.”

The Browns did not act on Braxton’s offer. But in the summer of 1754, three of the brothers helped stock the Sally with 17,274 gallons of rum, the main currency of the Rhode Island slave trade, 1,800 bunches of onions, 90 pounds of coffee, 40 barrels of flour, 30 boxes of candles, 25 casks of rice, 10 hogsheads of tobacco, 6 barrels of tar, and bread, molasses, beef and pork.

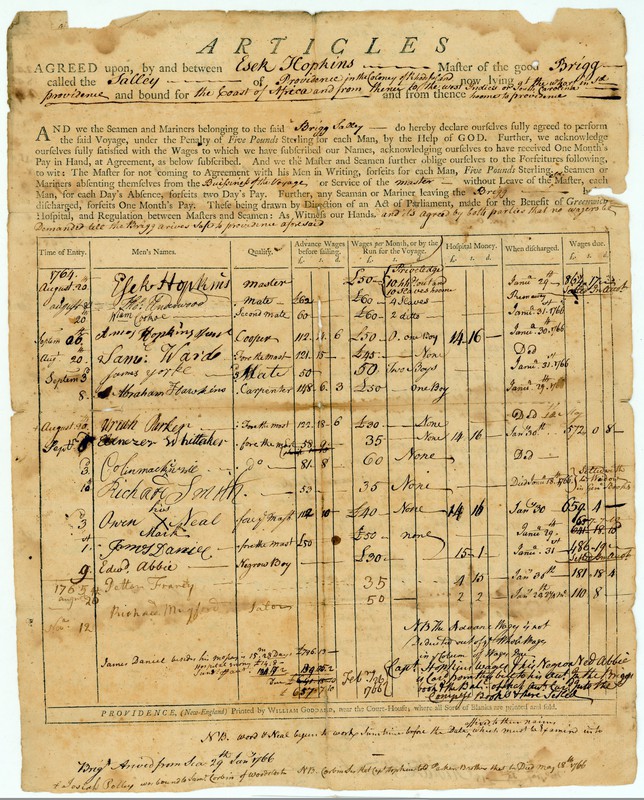

The Sally’s crew included a first and second mate, Hopkins’ personal slave and a cooper to make barrels for the molasses the Sally would receive in trade for slaves.

The Browns agreed to pay Esek Hopkins 50 pounds a month for the voyage. Although it was slightly less than the wages paid the first and second mates, Hopkins was also promised a fat bonus, or “privilege,” including 10 barrels of rum and 10 slaves. Most Rhode Island captains received a bonus of 4 slaves per 104 sold at market.

Because hard money was scarce in Rhode Island, the first and second mates were also offered slaves as commissions.

For the Browns, the stakes were high. For 50 years, Newport had been the colony’s major shipping port. The Browns, along with Gov. Stephen Hopkins and a few other merchants, wanted to make Providence the political and commercial center of Rhode Island.

“The Browns knew that the trade posed risks, but they also knew it could result in tremendous profits,” says James Campbell, a Brown University professor.

“They clearly anticipated a very profitable voyage.”

* * *

Hopkins, however, fared poorly in Africa.

With the end of the Seven Years’ War, transatlantic trade resumed; British and New England ships jammed Africa’s slave castles, trade forts and river mouths.

“Demand was great and prices were high,” Campbell says. “The seller had the upper hand.”

Hopkins had no choice but to sail a 100-mile stretch of coast, looking for deals. Worse, he didn’t understand local customs, which depended on gifts, tributes and bribes.

The trade, which dragged on for months, “involved an exchange of courtesies, gifts and negotiations,” says Campbell. “You had to establish your credentials and character before trade actually began.”

By mid-December, Hopkins had purchased 23 slaves. But the trading went slowly.

Hopkins gave King Fodolgo Talko and his officers two barrels of rum and a keg of snuff. It wasn’t enough. The next day, he gave another leader and his men two casks of rum.

On Dec. 23, he met with the king beneath a tree. He gave him 75 gallons of rum and received a cow as a present. The next day trading resumed, and Hopkins offered another 112 gallons of rum. He got one slave.

Later that day, the king demanded more rum, tobacco, iron and sugar for himself, his son and other officials.

Rhode Island captains spent an average of four months on the African coast; it took Hopkins nine.

“Hopkins was inexperienced as a slaver,” says Campbell. “You wanted to get in and out as quickly as possible. As long as a slave ship was close to land, there was a danger of insurrection. Moreover, you die when you’re on the West African coast. You’re being exposed to diseases like malaria and yellow fever. Your slaves and crews start to die.”

12 slaves.

That same day, one of his earlier captives hanged herself between the decks of the Sally.

* * *

Now, as Hopkins crossed a cruel stretch of ocean called the Middle Passage, death came almost daily.

3 women Slaves Dyed, Hopkins wrote in his trade book on Oct. 1.

The ink had hardly dried when, a day later, he wrote: 3 men Slaves and 2 women Slaves — Dyed.

On Oct. 3, 1 garle Slave Dyed.

In a letter to the Browns, Hopkins blamed the deaths on the failed slave revolt. The survivors were “so dispirited,” he wrote, that “some drowned themselves, some starved and others sickened and died.”

But the rate at which the Africans died “suggests an epidemic disease,” probably smallpox or dysentery, says Campbell.

Amoebic dysentery, carried through fecal-tainted water, was spread by the filthy conditions below slave ship decks. It caused violent diarrhea, dehydration and death. Traders called it the “bloody flux.”

The remaining Africans aboard the Sally were in a “very sickly and disordered manner,” Hopkins wrote to the Browns when he arrived in Antigua. The emaciated slaves, fed a gruel made of rice, fetched poor prices; some sold for as little as 4 to 6 English pounds.

By the time Hopkins returned to Newport, he had lost 109 Africans. For most investors, a 15 percent loss of life was an acceptable risk; Hopkins lost more than half of his human cargo.

A statue of Esek Hopkins stands in Hopkins Square, Providence, a triangular parcel of land bounded by Charles Street on the east, Branch Avenue on the south and Hawkins Street on the north. The statue was sculpted by Theodora Alice Ruggles Kitson. In the 18th and 19th centuries, this was the Hopkins family burial ground. In 1891, the city condemned the land and moved all the graves save that of Esek Hopkins to the North Burial Ground. In the background are the lights of St. Ann’s Church on Hawkins Street.

And, the Browns lost the equivalent of $10,000 on the voyage, says Campbell.

“The debacle represented a turning point for three of the brothers — Nicholas, Joseph and Moses — who thereafter left the trade for good,” says Campbell.

“It would be nice to say that they quit because of moral qualms, but there isn’t much evidence to support that, at least initially. More likely they simply concluded that slavery was too risky an investment.”

John invested in additional slave voyages — between four and eight more — and became a defender of the trade.

His younger brother, Moses, took another path.

Depressed, unable to sleep, he avoided the family counting house. In 1773 — eight years after the Sally’s voyage — he freed his six slaves. He was sure his wife’s death was the result of his role in the trade.

Joining other Quakers, Moses declared war on New England’s slavers.

One of his first targets was his older brother, John.

Paul Davis is a former staff writer for The Providence Journal.