In 1965,Sgt. Mal J. Wiley was one of 11 African American officers serving in Austin Police Department's force of more than 200 men.

“We were the East Austin police,” Wiley, 82, says of his first years as an officer after joining in 1960. That’s because all black Austin Police Department officers were assigned exclusively to the zones around East 11th and East 12 streets.

“We were denied privileges,” says Wiley, an Army veteran. “We received no promotions, no nice assignments. So we all got together.”

Anticipating their demands, the department’s leadership drew up plans for Wiley and his fellow officers to transition into regular departmental shifts.

“In 1966, Chief R.A. 'Bob' Miles had been meeting with community leaders, who asked, ‘Why do we never see black officers anywhere but in East Austin?’” Wiley recalls. “That all changed, too. Before, we always got a hand-me-down car. So they retired No. 26, the deep East Austin car. They added more positions. No more walking a beat. One officer got to drive the paddy wagon. We had regular shifts like everybody else. We started to get promoted.”

Life on the beat and beyond

The constants in Wiley's personal history — his love of country life, his experience in the recently integrated U.S. military, his devotion to his wife of 60 years as well as to his children, grandchildren and great-grandchildren, his service to his church and other civic groups — help to explain his groundbreaking tenure as an Austin policeman.

“Being reared in the country taught me to be more self-sufficient,” says Wiley, who grew up mainly in his grandmother’s care. “I learned how to depend on my own ability to accomplish what I had to do. I didn’t have a male figure, a father, so I had to look and see and figure out how to do it.”

Service in the Army also helped transform the teenager who spent his junior and senior years at Austin’s segregated L.C. Anderson High School.

“The opportunities in the Army were unbelievable,” he says. “I always wanted a family, but with no financing for college available, joining the Army was the quickest way to get back to the family life and the country life I always wanted.”

After the military, the police department provided the next anchor for his dreams.

“I didn’t know any policemen,” Wiley says. “But once I became a policeman, many of the things I learned in the country and in the military, such as how to talk to people and work with people, made it easier. I also didn’t know anything about street life and nightlife. But the people on Austin streets weren’t any different than the people I grew up with, and they had many of the same problems. I was used to dealing with people with issues.”

Just before joining the force, Wiley worked for the Texas Department of Health for $175 a month. Although the pay was lousy, he worked only 40 hours a week, plus he got state holidays, which seemed pretty good compared with some of his previous jobs. He and his wife, Esther Coffee Wiley, who grew up in a Blanco County freedom colony, were raising a young family.

“They posted that the city wanted some black officers,” recalls Wiley. “I had no idea I wanted to be a policeman. Five were going to take the test. I got the application on a Saturday; Tuesday I showed up with the rest of them to a whole room of young black men. I thought my chances were slim.”

Yet Wiley made the list of nine finalists and discovered he was selected for the academy in a circuitous way.

“At work, somebody said, ‘I’m looking for a man named Wiley, do you know him?’” he says. “I said, ‘I’ve known him all my life.’ He said, ‘Mal Wiley is leaving.’ The department hadn’t even told me.”

Before entering the academy, Chief Miles asked to speak to Wiley.

“People are going to say that black policemen are not full policemen,” Miles told him. “But you’re not going to have half a badge, you’ll have a full badge. You will run into people who are prejudiced. A white person might resist you. If they say, ‘Call a white officer,’ are you prepared for that?’”

Ready for just about anything, Wiley started training at the police academy on Nov. 13, 1959. There were only six black officers already on the force, all assigned to East Austin. They shared that one police car.

“If you drove Car 26, you worked a day shift from 8 a.m. to 5 p.m.,” Wiley remembers. “Everybody else worked 6 p.m. to 2 a.m. My first assignment was to East 12th Street. I worked with a partner, except on Tuesday nights. I didn't know anybody. I didn't know the places. But I got along.”

His main job? Going from bar to bar along the East Austin entertainment districts making sure everything was peaceful.

“If it concluded in you arresting someone, you arrested them,” he says stoically. “You put them in a shack the size of a small outhouse and called the police headquarters for them to be taken downtown and booked. If it was more than two people, it got crowded in there.”

Not too many interactions ended in arrests.

“If we could take care of it, we did,” he says. “I was good at calming them down. East Austin wasn't a place where you had to be afraid. I didn't run into anyone really vicious. I could talk to them. Now, if someone stabbed or killed somebody, we called a detective from a call box. There were no hand-held radios or two-way radios. Or maybe we flagged down a police car that was coming through.”

Once when he was patrolling 12th and Chicon streets, a woman threw lye in her husband's face because he was seeing another woman.

“Didn't get any on me, but my partner got some on his sleeve,” he says. “One of my greatest memories was walking 12th Street alone. Someone yelled, ‘Policeman, they are fighting over here!' One man was pretty beat up, and the other guy called me a four-letter word. He ran. I threw my nightstick. Fortunately or unfortunately, it hit him right in the back and he went tumbling. They were talking about it and acting it out all night. I could have run for mayor that night.”

One benefit of working East Austin on a regular basis — familiarity. As other Austinites who lived in the neighborhood in the days before integration tend to confirm, Central East Austin was like a small town where everybody eventually knew everybody else.

“If they gave you a hard time, they had to face you the next day,” he says. “The next day you‘d hear, ‘Officer Wiley, so sorry about what I did last night. You were nice to me, and I appreciate that.’”

He doesn’t remember seeing many Anglos in Central East Austin until the 1960s when they showed up in numbers to Charlie’s Playhouse, a popular blues and jazz club at 1206 E. 12 St. that closed in 1970.

“We had no problem with them,” he says. “Sometimes, they had a problem with us, usually college kids. They might say, ‘You can't arrest me because I'm white.’ I'd get them in the car, and say, 'When you get downtown, you can tell them your color. But here I don't care if you are white or black or whatever, you’re just drunk.’”

Where was Wiley on Aug. 1, 1966, when Charles Whitman climbed the UT Tower to gun down people on campus and nearby streets? Out of town, but he got back as quickly as he could.

Earlier that same year, he was photographed in front of the tower for an Austin Police Department promotional recruiting campaign.

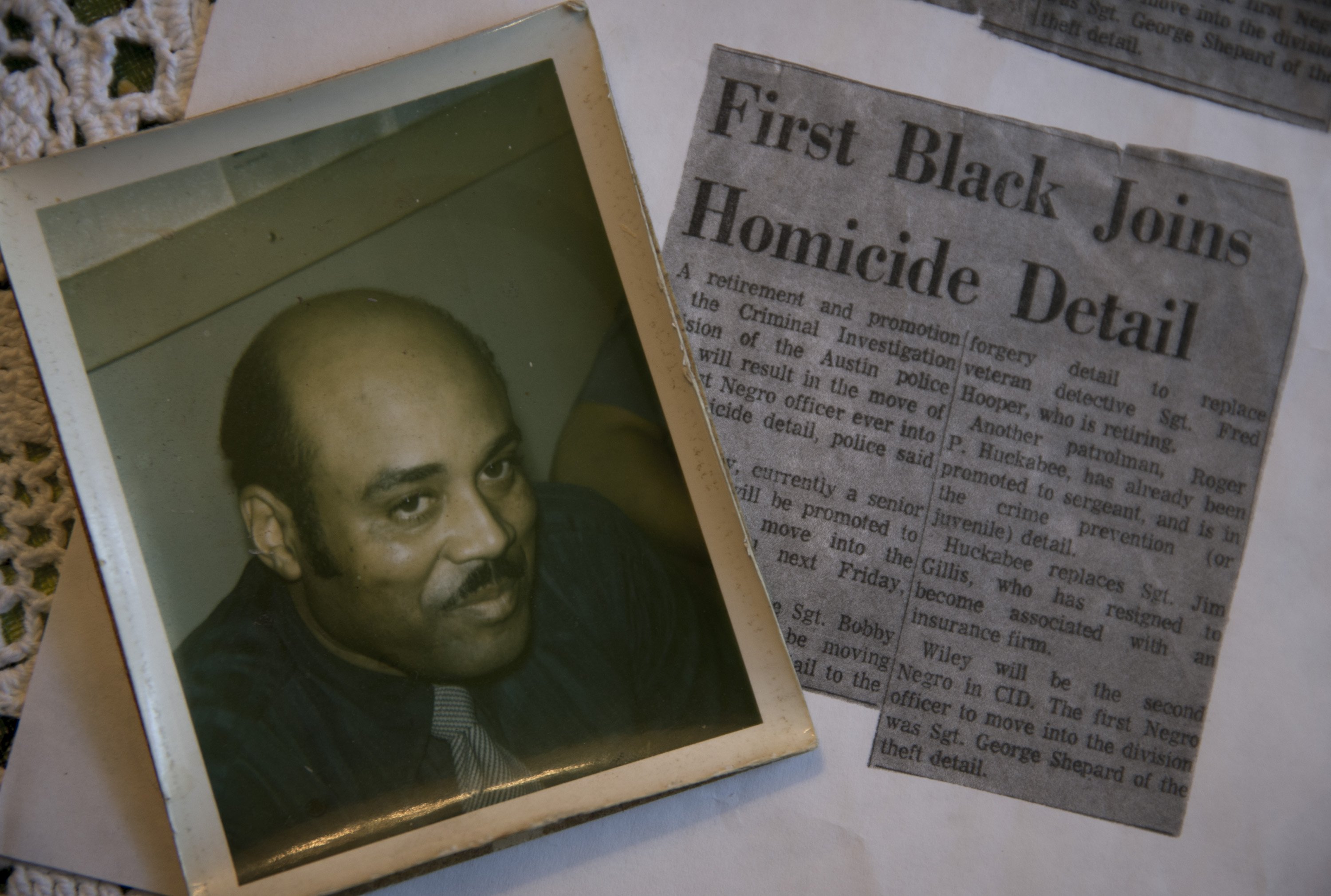

Wiley stayed on the force for just over 27 years, retiring May 30, 1987. Near the end of his career, he was assigned to counsel youth at the Thurmond Heights housing project. But before that, in 1971, he was promoted to the homicide squad.

Reflecting the language of the changing times, the newspaper article about that historic hire received different headlines in the co-owned morning and afternoon papers.

Austin American: "Homicide Detail Gets Negro."

Austin Statesman: "First Black Joins Homicide Detail."

“The article says, ‘This is news now, but it won't be in the future,’” recalls Wiley, who earned a B.A. in criminal justice. “That was true. Only two blacks, me and Freddie Maxwell, graduated from our class in 1960. He retired as a captain, but I’m older, which is why I can say I’m the oldest survivor of the segregated force. At that time, there were no black women, no women period. But I stayed around long enough to see a black woman, Cathy Ellison, promoted to interim police chief.”

The police department might have been segregated when Wiley joined it in 1960, but by 1985, when his son was murdered, he had earned the steadfast trust and loyalty of his fellow officers.

"I discovered then the respect they had for my dad," says daughter Kathy Robinson. "When my brother was killed, my parents were on their way to California. Someone at APD called every hotel in Las Vegas until they found my dad. They put an all-points bulletin out on their car to get them back here. Even at the funeral, from our house to the services at Mt. Zion, there were policemen along the route standing outside their cars saluting. That's respect."

The making of an officer

Mal Jordan Wiley was born on March 2, 1937, in the Hopewell community, a post-Emancipation freedom colony of three churches, two cemeteries and a two-room school in rural Walker County, northwest of Huntsville.

His father, Arzell Wiley, was a farmer and rancher. His mother, Estella Johnson Wiley, like her sisters, taught school. His parents divorced when he was young, but they remained friendly, and his father lived nearby.

“He was always just over a fence,” Wiley says. “Country life was his love.”

His mother worked in a number of tiny segregated Texas schools.

“My mother was gone most of the time,” Wiley says. “I was raised by my grandmother, Emma Johnson. My grandfather, Mal Johnson, was a prominent landowner and businessman. He ran a store, and he passed when I was 3. He was born a slave near Stone Mountain, Ga. He was freed at age 5, but he remembered slave auctions.”

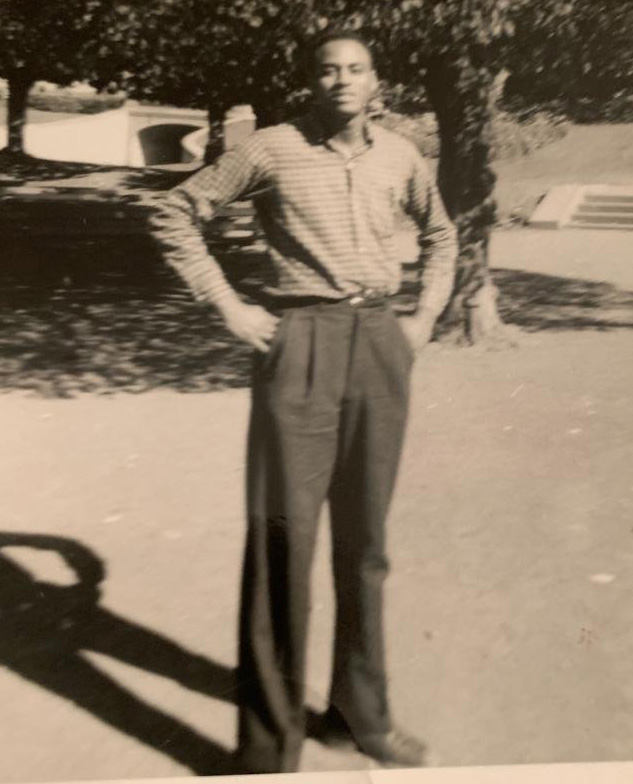

As a youth, Wiley spent almost all his time outdoors.

“That's basically what we had to do in those days,” he says. “Me and my dogs, horses and chickens. Whatever I could learn to play with.”

Wiley’s childhood was filled with country idylls: An aunt who drove a pair of gentle oxen, sandy creeks pocked with forbidden swimming holes. He attended the two-room Hopewell School, first grade through ninth grade, and heard some of the same lessons many times. There were no high schools for black students in his area.

“You'd have to make arrangements to go somewhere else,” Wiley says. “In Huntsville, I lived with an old lady, Aunt Rosie. My mother had roomed with her, as well as my sister. I spent one year there at Sam Houston High School. That’s not where I wanted to be.”

Luckily, Wiley’s sister had moved away to Austin to attend Tillotson College — predecessor to Huston-Tillotson University — in 1946. She liked the city, got married and started a family.

“I visited her and wanted to live in Austin,” Wiley says. His mother remarried and moved to Austin too, and by 1953 Mal had moved in with her and his stepfather in East Austin.

He played on the basketball team at the segregated L.C. Anderson High School in 1954 and 1955.

“I played center — at 6-foot-2,” he says with a chuckle. “Those were the days when there weren’t any 7-foot guys. Most of the guys were less than 6 feet. I played a little better than average. I could hold my own.”

Few distractions tempted this East Austin teen in the 1950s.

“I would go to church on Sunday nights — when there was nothing left to do — if there were girls hanging around,” he says. “What the preacher preached about, we didn't know. We were there for the girls.”

Wiley signed up for the Army on June 4, 1955, at a YMCA in San Antonio. After basic training, he was chosen for specialized electronics classes that led to assignments that he was admonished to keep secret.

“It was difficult but worked out very well for me,” Wiley says. “I went to school at night for technical training, since officers trained on that equipment during the daytime. We were learning to maintain Nike-guided missiles.”

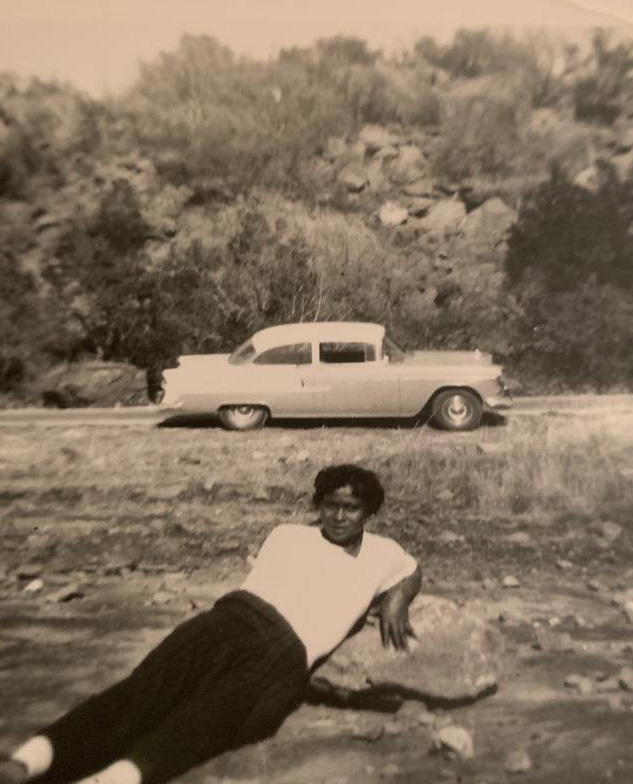

Not long after receiving his first assignment, he returned on leave to Austin, where he took a drive in his stepfather’s brand-new 1955 Chevrolet. The very first person he spotted through the windshield was his future wife, Esther Coffee Wiley.

“I asked if she wanted a ride. Quite naturally she wanted to ride in a new car,” Wiley says. “Now, she was a very good basketball player. Better than me, she thought. We had our very own team — and we won. First, though, we got to be good friends. After that, we started writing to each other and have never lost touch since.”

Esther tells her own version of their meeting.

“I was out walking that day,” she says. “But I already knew him from school and all his fancy hook shots. … I got married to the love of my life.”

The couple wed on March 22, 1957, at Mt. Horeb Baptist Church near Blanco. Esther grew up nearby in Peyton Colony. The country school there went to through the eighth grade, and her family paid county school taxes on their two ranches. When time came to enter high school, she moved to Austin and roomed on New York Avenue with the family of the Rev. B.F. Palmer, pastor of St. Stephen’s Baptist Church.

The only problem: Because she was from out of the county, the administration at L.C. Anderson wanted $80 a month in tuition. Since her family already paid school tax in Blanco County, they could not afford this extra fee.

“The school secretary, Gertrude Britton, told me, ‘You live at 1603 New York Ave.,’” Esther recalls. “’Just say that’s where your parents live.’ That way, I escaped the $80. Some people had to drop out because of that school fee.”

A natural helper, Esther received her B.A. from Tillotson College and her M.A. from Prairie View A&M before teaching at Sims Elementary School on Springdale Road. She crossed over to predominately white Pillow Elementary in the North Shoal Creek neighborhood as part of a program that integrated teachers before their students.

“All I wanted to do is teach children,” she says. “I taught school for 27 years before I retired in 1992. I couldn't wait to retire because (Mal) had already retired.”

Together, the Wileys attend Mt. Zion Baptist Church on East 13th Street. They raised two children, Kathy, who has two children, and Darrell, who had two children before he was killed in 1985 by a friend during an argument.

“The friend was charged,” Mal says. “I think he got a little time.”

An unaffiliated churchgoer as a youth, Mal Wiley eventually served on the board of trustees at Mt. Zion and worked with leadership to develop cottages for low-income elderly people.

“I was going to church, but I wasn’t really involved,” Wiley says. “I prayed: ‘Lord, if I had some leadership role in church, I could get more involved.’ The next day, a businessman stopped me on the street and said, ‘You are fixin’ to get a pastor, the Rev. G.V. Clark. I’d go on the board of trustees if you would be my co-chair.’”

During Wiley’s tenure in 1979, the congregation finished a new sanctuary that expanded seating capacity from 275 to 1,300.

“The police department assisted me all those years,” Wiley says. “If I had to take off time, they let me.”

He also served two terms as president of the PTA at Norman Elementary on Tannehill Lane and volunteered for five years with Meals on Wheels and More.

Connection to the land

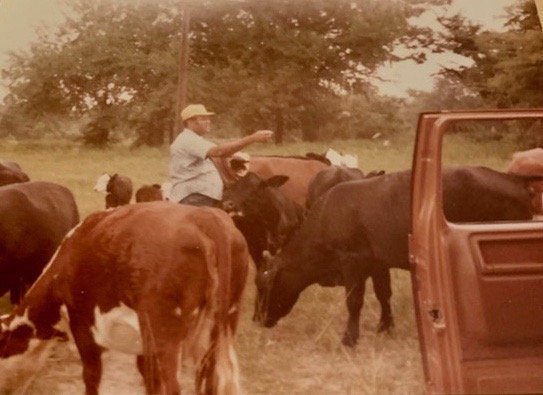

At every step of the way, Mal and Esther have longed to get back to the land. When his father died in a house fire in 1964, the couple went back to Hopewell to see what they could recover.

“There were 80 head of cattle, five horses as well as chickens,” Mal says. “What were we going to do? Everybody said, ‘Sell your cattle and rent out the land.’ We said, ‘Let’s try it. Saddle up the horses and let’s see what we’ve got.’”

For years, Mal commuted the 260-mile round trip to and from Walker County almost every weekend to tend to their land there. Eventually, that became unworkable, so they travel instead 48 miles to Esther’s family’s land in Blanco County when they need a breath of country air.

Having land allowed them to connect with their wider families, especially since some branches dispersed in disparate directions after Emancipation.

“I always longed to have a family reunion,” Mal says. “Everybody said we could do it at the ranch. I wanted to get together as many as I could. We had our first reunion at the farm outside Huntsville. We thought there would be 40 people. There turned out to be 400. The food didn’t run out. You drove down there and all you could see is black people. They came from all over the country. Some I’d never heard of.”

Looking back over the long road from Hopewell, Wiley reflects on what meant the most to him.

“The police department gave me the understanding and strength to complete what I had to do,” he says. “My greatest accomplishment — with a loving and understanding wife — was to raise two kids to be grown, to work in the community, to further education here, to keep a successful ranch and family business, and to support my wife’s church commitments on the state and national levels. The police department provided me with a nice retirement to do the things I want to do. I have reasonably good health and strength. And I would give it all to God, who has directed my life and my family’s life and surrounded us with good, loving people. To God be the glory.”