Deltona's sewer dilemma

IN THE SERIES: SEPTIC CRISIS | SAVING THE SPRINGS | DELTONA TANKS | COASTAL CONTAMINATION | COMPLEX AND COSTLY

DELTONA — If you want to rile up residents here, bring up septic tanks.

Some question whether the more than 23,000 septic tanks in the city really cause environmental harm and argue there should be "no forced sewer."

Others admit septic tanks may harm water quality, but say residents can't afford to pay the expensive monthly bills if they are required to hook up to city sewer.

Ultimately, the debate over septic tanks all comes down to money. Of the more than 30,000 homes in Deltona — Volusia County's largest city — only about 6,000 have city sewers. The rest use septic tanks. And that number keeps growing. The city topped Volusia County in the number of new septic tanks added between 2014 and 2018.

The city also leads the state with the most expensive wastewater rates. Many residents pay between $80 and $150 a month, or more.

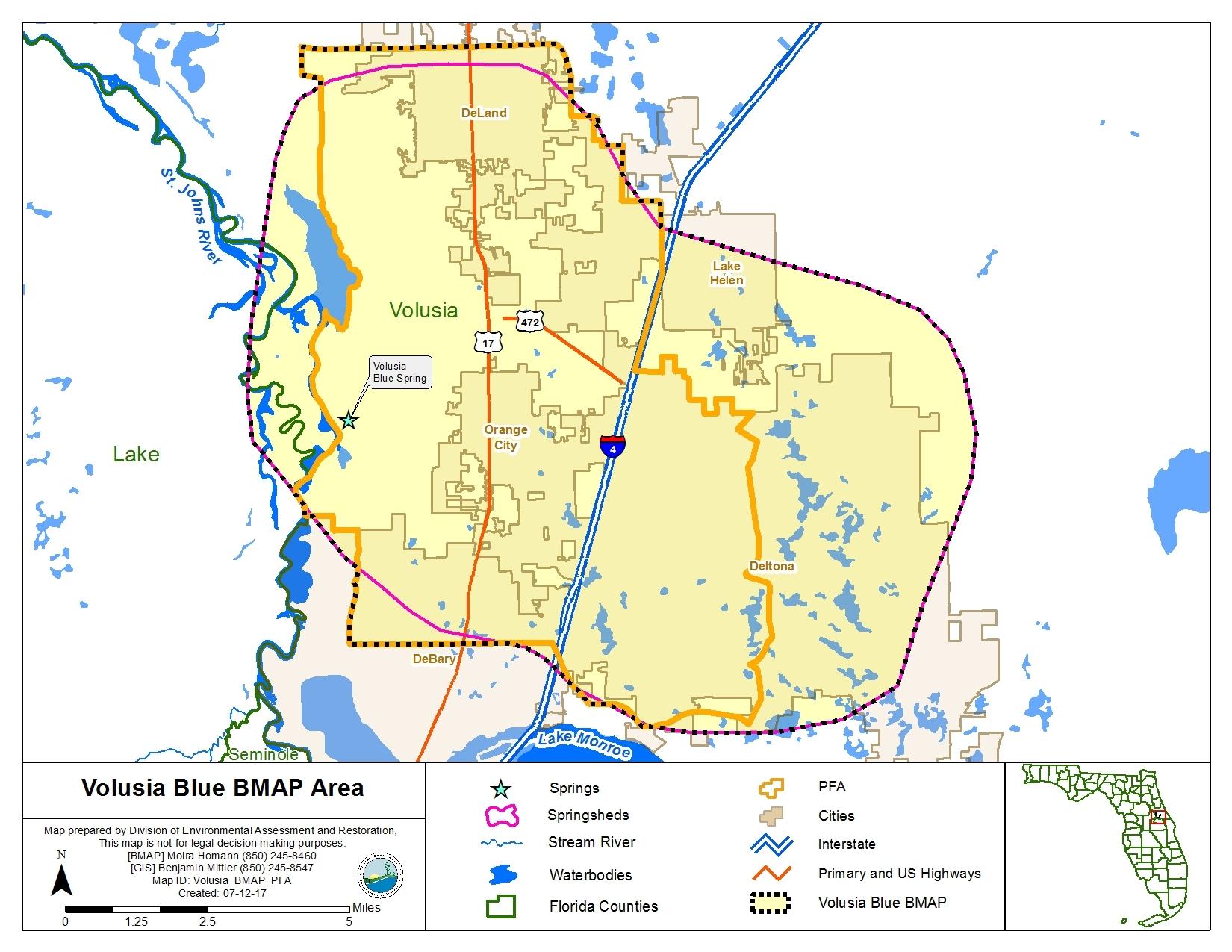

New state rules designed to restore the water quality in Blue Spring, five miles to the west, have added another dynamic to the debate over septic versus sewer.

When the Blue Spring Basin Management Action Plan becomes effective — most likely after a court challenge this fall — residents and area governments will face new rules to reduce the flow of nitrogen to the aquifer that feeds the spring. Along with a range of projects such as better stormwater treatment, the rule targets some 24,000 septic tanks in a "priority focus area" that includes parts of DeLand, Deltona, DeBary, Lake Helen and the unincorporated county and all of Orange City. Over the next 20 years, the septic tanks will need to be enhanced or upgraded, or homes will need to be hooked up to city sewer.

None of the tank options are cheap. Estimates range from $15,000 to $25,000 per home.

“It’s all fine and good to say we’re not going to force sewers,” said Deltona Mayor Heidi Herzberg. But once the new rules to protect and restore Blue Spring go into effect, she said, there may be "no way out, and I think people are unaware of the cost."

While the realities of springs protection may not have set in yet, many residents are keenly aware of Deltona's costly wastewater rates.

Wastewater rates range from $16.48 to $21.43 per 1,000 gallons, depending on the amount of water used. That means customers who use 5,000 gallons of water a month pay about $80, and customers who use 8,000 gallons a month pay $146. In a 2018 statewide utility rate survey by Ratelis, Deltona's rates topped the list as most expensive, and more than double what most utility customers pay across Volusia and Flagler counties. And the city is considering another rate increase.

Utility spending

The Blue Spring restoration rule is the latest chapter in Deltona's long-running debate over forced hook up to city sewers.

A search of News-Journal stories over 20 years reveals no push by the city to force its more than 90,000 residents to give up septic tanks and hook up to city sewer. City officials have suggested it would be more economical if the utility had more customers, but the city has never taken any action to force people to hook up to city sewer.

Yet resident fear of being forced to hook into the city's sewer system has been ever present, and has contributed to significant distrust in local government.

The trouble really started more than 40 years ago, when the city began as an unincorporated sprawling subdivision in the scrubby woods between Lake Helen and Enterprise in the early 1960s. The original developers installed a private utility for water and wastewater. But once the developers allowed other home builders to work in the community, Volusia County rules didn't require the continued expansion of wastewater lines.

As meandering growth continued across the 41-square-mile community, builders installed septic tanks rather than hook into the wastewater system. So, few new customers were being added to help share in the expense of running the utility.

Today, new subdivisions are required to put in reclaimed lines and wastewater lines and hook up, but individual homes built on scattered lots across the city are not. City sewer is generally available in an area along Normandy Boulevard near Deltona Boulevard, along Providence Boulevard between Fort Smith and Saxon boulevards, and near Howland Boulevard and Fort Smith Boulevards.

The sewer debate surfaced as far back as 1999, four years after the city incorporated, when the state Department of Community Affairs suggested the city should consider protecting its water resources and lakes by expanding the sewer system.

It came up again in 2003, shortly after the city bought the private water utility for $59.5 million, raising the money with the sale of $81 million in revenue bonds that were also used to help pay for repairs and upgrades.

The campaign picked up steam in 2008 when the city instituted a series of wastewater rate hikes to be phased in over five years. Herzberg and News-Journal stories from the era indicate the rate increases were advised by a consultant so the city could upgrade its sewer system. The previous owner had let it fall into disrepair after a period of years with no rate increases.

That led to concerns among wary homeowners with septic tanks. By 2012, the campaign had a name, with calls for "no forced sewer" as the city made plans to expand its wastewater treatment system to make way for new commercial and residential growth. A group of fiscally conservative city residents, including frequent city critic Jamison Jessup, pushed against the high cost of wastewater rates and the continued rate hikes.

Jessup said he and other residents felt like the city wasn't being truthful about the reason for the rate hikes. He called it "lies of omission." He echoed a concern voiced in 2012 by his friend Fred Lowry, then a city commissioner and now a county councilman, who said city staff sold the rate hike in 2008 as needed for bond obligations, not capital improvements.

But city officials disputed that, then and now, saying lenders expected the city to maintain and improve its utility system.

Around the same time, state officials began discussing the need to eliminate some septic tanks in order to clean up the water at Blue Spring. The two issues became linked. The "no forced sewer" proponents feared Blue Spring would be used as a sword to force them to sewer.

Jessup and others also were troubled by the debt the city took on to build the expanded and new treatment plants.

Deltona native Michael Bowman isn't convinced Deltona's septic tanks add to the pollution in Blue Spring or even the city's lakes. But he is convinced the city's water system debt — more than $135 million — "will wind up being the downfall of Deltona."

"They're going to bankrupt the city," he said.

Restoring Blue Spring

State legislators adopted new rules in 2016, requiring protection of the spring basins for 13 of Florida's "outstanding springs."

State studies concluded that much of Deltona falls within the 108-square mile Blue Spring basin, or watershed, meaning rain that falls in the community eventually flows to Blue Spring. Wastewater flowing from the city's septic tanks flows in a similar direction.

Nearly half the city — west from Providence and Howland boulevards, south to Fort Smith, and along Saxon to Doyle Road — falls within the "priority focus area" for restoring the spring.

That surprised city resident Terry Ellis, and many others. When Ellis first learned about the new state requirements, she was worried what it might mean for residents. She was relieved a little to learn the state plans to make grant programs available to help residents pay for septic upgrades, but still remains concerned.

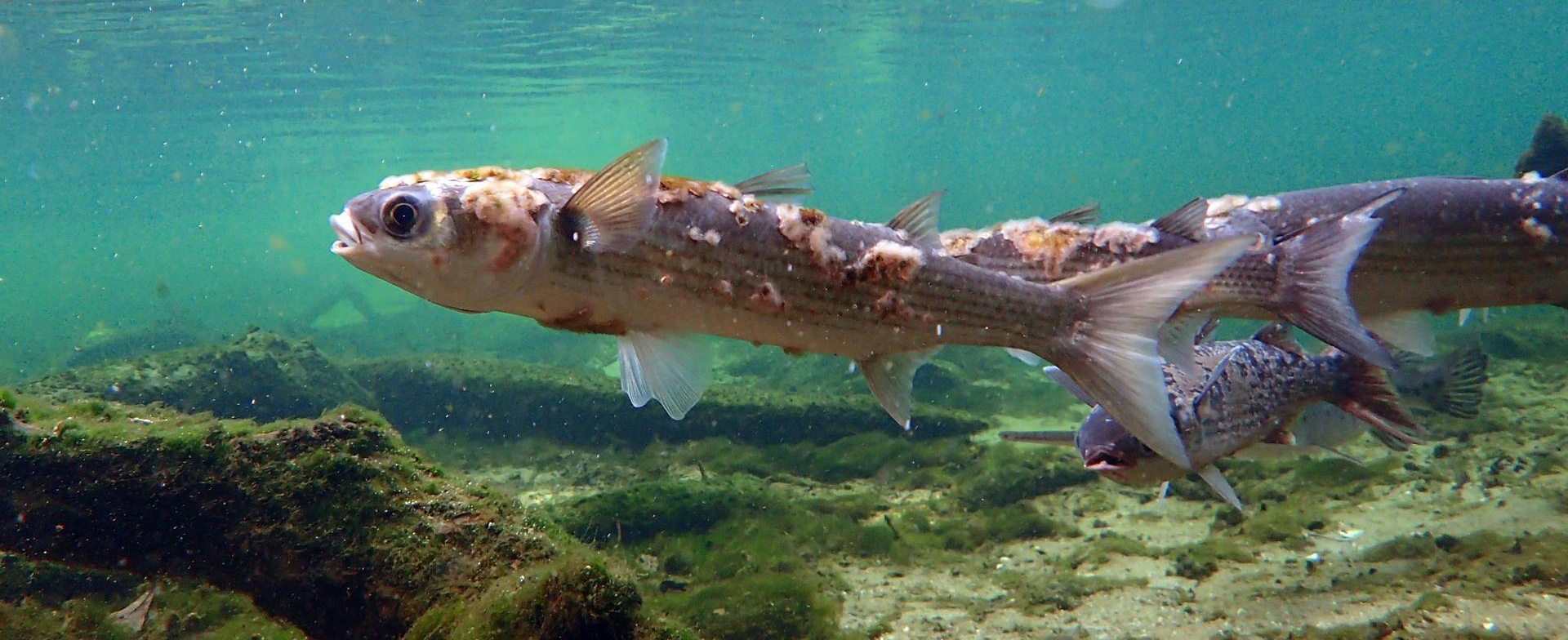

For now, the Blue Spring action plan is on hold. The Save the Manatee Club filed an administrative challenge, arguing the plan doesn't do enough to improve water quality in the spring, a winter refuge to hundreds of manatees that live in the St. Johns River and beyond. A hearing is scheduled in September.

One thing is certain: when the plan goes into effect, the western part of Deltona will be subject to the plan's stringent rules requiring septic and sewer upgrades over 20 years.

“People need to understand that the state and water management districts are serious about these springs,” said Dave Denny, the city's former utilities director, in an interview before his recent retirement.

Anyone who builds on a vacant lot less than one acre in size within the priority focus area will be required to either hook up to sewer or install a newer advanced septic treatment system such as one with pumps that circulate wastewater in the tank to remove more nitrogen. The more advanced tanks and drain fields cost twice as much or more than a conventional tank and drain field, up to $20,000. They also require $200 to $300 a year for maintenance fees and inspections.

At some point, any resident who needs a new septic tank and drain field or septic tank repairs also will be required to upgrade or enhance their tanks to remove nitrogen.

When the Blue Spring plan's requirements become fully effective, Herzberg said "it’s definitely going to be an interesting time.".

Sewer rate fears

The vehemence against city sewers seemed "bizarre" to Troy Shimkus when he moved to Deltona about three years ago. Then he learned about the expensive wastewater rates.

Hooking up to sewer "would be a massive increase for people," said Shimkus, a founder of the civic group Deltona Strong that tries to shed light on some of the more difficult topics in the city.

Why, he asked, would a resident want to pay $5,000 to $10,000 to hook up to a city sewer line, and then pay a monthly bill of up to $150 monthly depending on water use?

That expense is the biggest hindrance to talking about converting private septic tanks to city sewer, he said, even if the city utility would do a better job than residents "maintaining their own systems."

No one understands the wastewater challenges in Deltona more than Denny, who worked with the city and two former owners of its utility system for almost 40 years. He was hired by the city when it bought the utility. He retired once and was lured back out of retirement to run the utility again before stepping down earlier this year.

The rates are high in part because the utility has so few customers on sewer, so the wastewater lines are a scattered patchwork, with little opportunity for economies of scale, he said. If more homes were connected to sewer, he said, perhaps the rates could be lowered, or at least stabilized.

Herzberg, a hair stylist, compares the wastewater rate structure to running a hair salon. Shop owners pay the same rent whether they have 500 clients or 1,000, she said. But if the cost of that rent is spread among 1,000 clients rather than 500, it brings the cost down for everyone.

Jessup said his biggest objection is cost. At anywhere from $15,000 to $20,000 a home to run sewer lines in neighborhoods, he said, "if you multiply that out in Deltona, that's a lot of money." And, he maintains, even if state or federal grants or dollars cover some of the cost, it's still the public's money.

"Governments don't have their own money," he said. "When they say it's free, I'm going to be paying for it."

Jessup isn't opposed to putting the issue of sewer expansion before city voters, he said. "If the citizens want to vote on something, I trust the citizens."

Deltona resident Mark Metzger said people on both sides of the issue “spread an awful lot of misinformation and tend to fearmonger.”

"People are afraid they're going to be stuck with these big bills," said Metzger, who moved to Deltona five years ago from upstate New York. "The reality of it is we’ll never see sewers throughout Deltona in our lifetimes because they don’t have any more money."

Metzger said the city should do more to calm the fears and be more transparent. Instead, he said, "there seems to be a lot of cloak and dagger when it comes to the water department.”

No grand plan

Herzberg and Denny insist the city has no grand plans or the money to expand its wastewater lines into residential ares across the city and force residents to hook up

"The city can’t afford to tear up 460 miles of roads and put sewer lines in," Herzberg said. "It's a horrendous amount of money."

On the other hand, she said, residents might wish city sewer was available when the state requires them to put in newer, more expensive septic tanks.

To assuage fears, the city adopted an ordinance in 2018 stating even if city sewer lines are laid in front of individual homes, hook up is optional. However, officials with the Florida Department of Environmental Protection stated the Blue Spring rule supercedes a city ordinance, meaning when the rule requires a homeowner to hook up if city sewer is available, it won't matter what the city ordinance states.

The city is looking to expand sewer to commercial areas. City officials said the lack of city-wide sewer access is one of the biggest limitations to commercial growth. Despite its size, Deltona has lagged in commercial development. Herzberg said a developer wanted to build a Dunkin Donuts near the intersection of Saxon and Interstate 4, but there was no sewer access and the store wasn't built.

“If you don’t have sewer available, it somewhat limits what commercial entity can go there," said Denny. “Even if they decide they want to build, they’re limited on what they can build. A lot of our commercial lots just aren’t that big."

Reducing contamination

The Blue Spring restoration plan includes goals for Deltona and other cities to take a range of steps to reduce nitrogen in groundwater. The city's projects to expand reclaimed water treatment and distribution will reduce nitrogen and the amount of water used from the aquifer, said Denny. The city and other West Volusia utilities also are under a mandate to increase the flow of water at Blue Spring.

Any action to reduce nitrogen to groundwater could also benefit water quality in the city's expansive lake system, which the city doesn't test. State testing in the city's Butler chain of lakes showed septic tank wastewater might be finding its way into the groundwater. For example, the testing found several times more than the minimum detectable level of sucralose, an artificial sweetener used in diet sodas.

“It doesn’t surprise me at all that you would find something that you would typically find coming out of a drain field in lakes," said Denny. “We’ve got a lot of homes near lakes and the majority of them are on septic tanks.”

About This Series

DAY ONE: Hundreds of thousands of septic tanks leak nitrogen into Florida's water supplies, helping fuel algae blooms.

DAY TWO: Restoring water quality in the area's springs will require removing or upgrading thousands of septic systems.

DAY THREE: Deltona has more than 23,000 septic tanks. "No forced sewers" campaign is colliding with Blue Spring restoration.

DAY FOUR: Cities on the east side of Volusia grapple with septic tanks along Mosquito Lagoon and the Halifax and Indian rivers and the damage they may be causing.

DAY FIVE: Paying to convert septic tanks to sewer is no easy — or cheap — task.