SAN DIEGO — Donald Lewis is among more than 300 people who live in one of three San Diego tent shelters erected for the homeless in recent years.

Lewis, 48, said he came to the shelter about a month ago after living in a park. But time on the streets led him to become increasingly fearful of being overrun by rodents, disease or drugs. Since he arrived at the shelter, Lewis said he hasn’t had to worry about being robbed or beaten, has gained self-respect and is able to get up every day and speak positively about something in his life.

“I just want to get my life back together,” he said. “It’s a lot more encouraging.”

Austin business leaders largely have based their efforts on addressing homelessness on strategies used in San Diego, where in 2017 a scourge of hepatitis A tore through its homeless community, killing 20 people and sickening nearly 600 more.

Out of that devastation emerged a broad strategy to attack homelessness on a variety of fronts, including temporary pop-up shelters, large storage facilities, cleanup campaigns and increases in police enforcement of rules on public camping and encroaching on the public right of way.

Many cities and private groups throughout the country took notice, sending delegations to tour temporary shelters and storage centers — among them, leaders with the Greater Austin Chamber of Commerce. They came back to Austin with a plan to build a Sprung shelter, a brand-name tent facility made of tensioned fabric, to house 300 people, and to mirror San Diego’s family reunification program, which has seen an estimated 1,800 reunited with relatives in the last two years.

“They had a particular situation with a very significant homeless population that created some real health and safety issues,” Austin chamber Chairman Brian Cassidy said. “They were kind of in a position where they had to do something quickly. And they, you know, used this method.” He called it the gold standard for how to how to do something to address the crisis quickly.

The chamber on Nov. 7 announced the ATX Helps campaign to raise $14 million to erect the shelter, saying it could fill a gap in Austin’s homeless service network and get people into shelter immediately.

But exactly how that facility will interact with Austin’s current homeless outreach, intake and housing systems has yet to be seen. Some worry the new shelter could siphon money away from longer-term housing priorities sought by the city, or lead to increased criminalization of homeless people in Austin.

As in San Diego, the success or failure of Austin’s larger efforts will depend upon the service providers who run the facility, and how city leaders, state government and local service providers come together, or don’t.

Shelter life

For many still living on the streets of San Diego, the new temporary shelters spark fear and uncertainty. Several said they’ve seen facilities in the past where people are robbed, beaten or raped regularly, or that have barriers to entry that either keep them from getting in or get them kicked out.

But those living in the largest of the three shelters in San Diego, which is run by the homeless service provider the Alpha Project, say the facility is a godsend.

James King, 65, said having a place to go has been a tremendous help.

“When I came in here I could barely walk from sleeping on the ground at my age,” he said.

King said he’s been homeless for 20 years, and has sometimes worked day labor shifts that allowed him to get into hotels for a few nights, but nothing more permanent. He said he’s been on a housing waiting list for 17 months, and is still waiting to hear back.

San Diego Mayor Kevin Faulconer said he picked the locations for the shelters himself, and promised to make areas where they — and their accompanying storage facilities — stand cleaner and safer than they were before.

Alpha Project workers and shelter residents clean the facility and surrounding area frequently.

Alpha Project Chief Operating Officer Amy Gonyeau said two nearby elementary schools have become big supporters of the shelter because of how significantly the area’s cleanliness and safety improved after the shelter began operating. She said the facility sends outreach teams in golf carts or vans to work in the surrounding area, and it offers a work program for residents to pick up trash throughout the city.

“We always stress that that’s the kind of agency we are. We’re not required to do it. We just do it because the community deserves it,” Gonyeau said.

Kenneth On, who had been homeless periodically for the last seven to eight years, said the shelter is a great place to be. On has spent the last year at the shelter.

“Through it all, I was able to get on (an) income, which will allow me to pay for my rent for further opportunities and find my way back to being a productive member of society,” On said. “I’d still be out on the street without the Alpha Project.”

San Diego’s three shelters have provided nearly 700 new beds for people who are homeless to help them shift from life outside to more permanent options.

But while the shelters provide new temporary housing options quickly, advocates for homeless people in Austin and San Diego have raised concerns that such shelters could siphon resources away from long-term projects on which city leaders have focused, allow police to arrest more people who are homeless and serve as little more than another endpoint, rather than a through point for many who stay there.

Cassidy, however, says that while Austin city leaders focus on long-term housing, there has to be another option to address the immediate need for shelter.

“People talk about wanting to address the issue, (but) we can’t do that unless those folks do have somewhere to go,” Cassidy said.

Moving on

While the new San Diego shelters have added hundreds of beds, there still is a significant gap between shelter space and the number of homeless people living in the city. The number of people moving on to permanent supportive housing or other long-term options from the shelters is still relatively low, though city staffers said the figure is improving.

Faulconer said his “action-oriented approach” barred homeless people camping in their own tents and makeshift structures, and created space for people to sleep and store their belongings when previously they had no other option. In addition to the bridge shelters, the city also has a handful of parking lots that provide a safe place for people to sleep.

PHOTOS: How San Diego is dealing with its homeless crisis

Faulconer acknowledged that long-term housing still is a critical piece of the puzzle, but said the public health crisis required a solution to get people into housing and off the streets immediately, rather than waiting for other housing options to be built.

A point-in-time count conducted Jan. 25 found that at least 8,102 people were living on the streets or in homeless shelters in San Diego County on any given night. In the city, officials counted just over 5,000 people, including 2,600 without shelter, according to the San Diego Union-Tribune, though homeless advocates say the actual figure is far higher. Citywide, there are a little more than 2,000 shelter beds available, city records show.

Even now, many living on the streets say they are waiting to get into shelters or some other form of affordable housing, but can’t.

Bridge shelters

The three new shelters vary in size, and each caters to a particular type of clientele.

One shelter provides 150 beds for single women or families with children. A second provides 200 beds to veterans. The third and largest facility provides 324 beds to single men and women.

The tent that housed single women and families was moved to a new location to serve as a fourth shelter after city leaders elected to move single women and families into a city building earlier this year.

These bridge shelters are not intended to serve as long-term housing options. Ideally, people coming in would exit within 90 to 120 days.

Since the facilities began opening in December 2017 through this September, they housed a total of 4,814 people, including 813 single women or families with children, 1,644 veterans and 2,375 single adults, city records show.

Across the three shelters, an average of 1 in 4 people who entered them moved on to permanent or longer-term housing. Those housed at the shelter for single women and families had the best positive exit rate at 40%. Veterans fared worse at about 21%, and other single adults even lower at 14%, leaving about 77% of those served since the shelters opened without a permanent long-term housing option.

Michael McConnell, an advocate for homeless people, referred to many of the San Diego mayor’s efforts as Band-Aids that ignore the structural issues of the city’s homeless service system.

“He’s not converting motels or hotels. He’s not trying to create tiny villages. He’s done some work on (alternative dwelling units) to make those easier to build. He’s changed some parking requirements, but nothing has been implemented to increase the supply of permanent housing for folks who are homeless,” McConnell said.

McConnell said shelters are a part of the system, but one that should be focused on housing solutions that move people through quickly.

“I compare them to an emergency room,” McConnell said. ”Emergency rooms tend to be small. Then you quickly get people where they need to be, whether you put them into surgery, you put them into a hospital bed, you get them to a rehab facility or you get them back into their home with proper care. That’s what emergency shelters need to be.”

Austin camping rules

Austin City Council members in June voted to allow camping in public spaces, provided those doing so did not pose a threat themselves or others, or block the right of way, a move local criminal justice advocates said decriminalized homelessness and helped those living on the streets to come out of the shadows. The council modified those rules in October to ban camping on sidewalks, near homeless shelters and business entrances. But, by and large, people who are homeless still can find places to sleep without fear of arrest or citations, provided they follow the rules.

In San Diego, while the shelters provided more housing options there, they also paved the way for police to enforce laws against blocking sidewalks and public camping more vigorously than before. It’s a practice local advocates fear could return to Austin.

The October rule change led Austin police and cleanup crews to clear out encampments around the Austin Resource Center for the Homeless. State officials also have been clearing encampments from underpasses controlled by the Texas Department of Transportation, instead referring people to a campsite at U.S. 183 and Montopolis Drive that provides bathrooms, showers, food and other services until the temporary shelter planned for Austin is built.

San Diego police Capt. Scott Wahl said encampments still spring up frequently in San Diego’s urban center, but police constantly are working to dismantle them and either get people who are homeless into shelters or make them move.

“We try to address them every single night, and again: ‘We’ve got a place for you to go. We’ve got a shelter. It’s cleaner, It’s healthier, It’s safer. It’s a better environment for you,’” Wahl said.

Due to a court settlement, people in San Diego still are allowed to sleep on the streets from 9 p.m. to 5:30 a.m. So police show up early in the morning to force people to move, and they still can enforce bans on tents overnight.

“The biggest issue, you’ve got to have a place for folks to go,” Wahl said. “If you don’t have a place for folks to go, the community is very divided on how this issue should be addressed.”

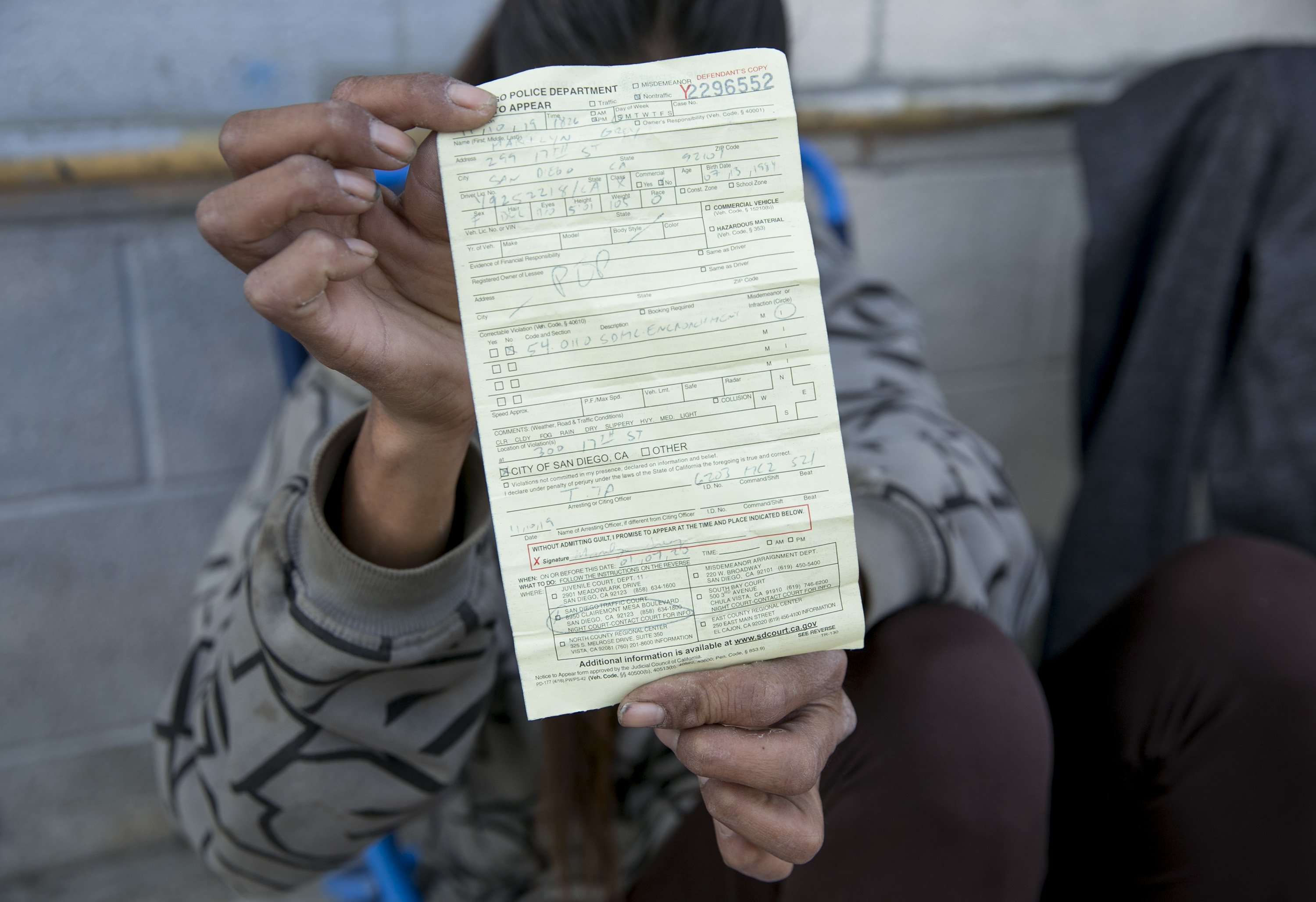

San Diego police have put in place a policy for enforcement that escalates as officers encounter a person multiple times. During the first encounter, they are warned. The second results in a citation. The third is a misdemeanor charge, and the fourth prompts an arrest, provided they do not accept shelter.

While police clear out encampments, they also deploy homeless outreach teams to provide care and advice to people who need it.

McConnell said San Diego’s homeless efforts focus too heavily on police, and amount to what he says officers refer to as “whack-a-mole” tactics that only move people around.

“The front of your effort has to be homeless service providers,” he said. “As long as you have law enforcement at the front, you are going to fail.”

In Austin, Chris Harris, a criminal justice advocate and organizer, is concerned an increase in shelter beds, no matter how effective at providing services, will lead to an increase in the criminalization of homelessness.

“We want to make sure people’s rights are protected while providing people with safer, better places to be, and ultimately to housing,” he said.

Downtown Austin Alliance President and CEO Dewitt Peart said Austin’s Sprung shelter will be part of a continuum of care for Austin’s homeless, and another resource for people to go immediately. Before they were left without any other choice, he said.

“We know that (this) is not the answer to solve Austin’s challenges,” Peart said. “It’s is a gap that we see from the business community that we think the private sector can step (into) and act very quickly.”