Fortifying Florida’s coastlines

State’s infrastructure the bullseye as water issues engulf coastal communities

By Tom McLaughlin, GateHouse Florida

Hurricane Irma’s mid-September run up the Florida peninsula provided one of the sternest tests the state’s energy grid could undergo.

Officials estimated that more than 60 percent of Florida’s power customers, some 6.7 million, lost power as the monster storm climbed the state, wreaking havoc from the Keys to Jacksonville. The state’s largest power company, Florida Power and Light, confronted outages to 90 percent of its customers.

Experts said most of the damage to the grid was caused when debris battered power lines amid winds often exceeding 100 mph.

But it was the recovery, not the devastation, that riveted the attention of Julie McNamara, an energy analyst with the Climate & Energy program at the Union of Concerned Scientists. Just one week after the storm passed, Florida Gov. Rick Scott announced that more than 90 percent of all power had been restored.

“Many of those customers were back on line in just one or two days,” McNamara said. “That’s a big step forward.”

For McNamara, building resiliency into the energy grid is key in a world where sea levels are rising and climate change could contribute to the formation of more powerful tropical systems.

“Resilience is not about preventing power outages, it’s making the grid better for everybody. It’s accepting the grid won’t be perfect,” she said.

Strengthening the grid

By the time Hurricane Irma made landfall in Florida, the state’s power companies had been armoring themselves for more than a decade against the kind of beating inflicted in 2004-05, when eight hurricanes hit the state.

In 2006, at the urging of the state’s Public Service Commission, the investor-owned power companies committed to spending billions to protect delivery systems and find ways to improve the efficiency in restoring power after widespread outages.

“It’s impressive seeing the level of preparation,” Jimmy Patronis, Florida’s chief financial officer and a former PSC member, said just before Irma made landfall in Florida. “We are so much further ahead than we were.”

FPL, serving customers in 35 of Florida’s 67 counties, invested nearly $3 billion hardening its grid, which stretches along the Atlantic Coast from Miami to Jacksonville, and along the Gulf of Mexico from Naples to Manatee, said spokesman Chris McGrath.

The hardening included installing more than 100 concrete power poles, capable of withstanding 145 mph winds, in Daytona Beach alone. In Sarasota and Manatee counties, FPL enhanced more than 62 main power lines, inspected 122,372 power poles and installed more than 3,231 “intelligent” devices that detect and prevent power problems.

Duke Energy, which also serves customers in 35 Florida counties and major cities that include Orlando and St. Petersburg, invested approximately $2.4 billion to strengthen its grid, including replacing 802,000 power poles, according to company spokeswoman Ana Gibbs.

During the same time period, Gulf Power in Northwest Florida invested more than $225 million in storm hardening projects across the region.

The power companies also invested in technology that allows technicians to know where outages are occurring and use computers to confirm power has been restored, Patronis said.

As successfully as the power companies were able to restore electricity to most of the state’s residents, there were infrastructure failures as well, McNamara said.

In Homestead, home to the Turkey Point nuclear plant, a failure in a reactor’s cooling plant during Irma forced engineers to shut down the single reactor left online as the storm approached.

The St. Lucie Nuclear Plant also had to be shut down, after Irma passed, to allow workers to clean ocean salt off of machinery in a switchyard — “the area where electricity moves from the generators to power lines,” the TC Palm website reported.

“We know risks from flood issues still exist, and if sea level rise is not figured in, it could be a costly issue to address in the future,” McNamara said. “We believe there is still work to be done.”

That work, McNamara said, should include the big power companies using solar energy more effectively.

Also needed are strategies to protect critical utilities, ensuring that first responders are headquartered in locations that allow them to react quickly in times of crisis and safeguard “vulnerable populations” like those living in nursing homes, she said. “Who do we need to bolster and who needs support soonest?”

The Union of Concerned Scientists stresses that every storm is different and each will pose different challenges.

While Irma was primarily a wind and storm surge event for much of the state, Hurricane Harvey just weeks before had been mostly about rainfall, causing horrific flooding in Houston, which, like most of Florida, is in a low-lying area.

No. 1 issue: Stormwater

Coastal communities across the United States, indeed across the world, have come to recognize that sea level rise is — if not an immediate concern — certainly a future dilemma.

As warming oceans expand and glaciers and polar ice sheets melt, federal scientists are forecasting sea levels 6 to 12 inches higher around Florida by 2030 and 9 to 23.6 inches higher by 2050.

A Government Accountability Office report filed in September estimated “coastal property losses from sea level rise and increases in the frequency and intensity of storms could range from $4 billion to $6 billion per year in the near term (i.e., 2020 through 2039), increasing to a range of $51 billion to $74 billion per year by late century.”

Dealing with stormwater is the No. 1 infrastructure issue related to sea level rise in Florida, said Jason Evans, a landscape ecologist and assistant professor of environmental science and studies at Stetson University in DeLand.

“Rising seas already are having an impact on stormwater and wastewater systems around Florida,” he said.

“If we think about into the future with sea level rise, if we don’t upgrade these wastewater systems and think about groundwater infiltration and tidewater infiltration, we’re seeing it’s going to become more and more of a chronic problem,” Evans said. “It’s a huge deal.”

One of the communities Evans works closely with is Satellite Beach.

“They’ve been very proactive in trying to identify where they have issues with flooding from stormwater and they’ve been upgrading their system,” he said.

Much of the city’s stormwater system, though, is designed to drain into the Indian River Lagoon. With rising tides, on top of seasonal high tides, pipes designed to let the stormwater flow out to the lagoon through gravity are no longer working as designed.

“And when you get a seasonal high tide and you get a heavy rainfall event, some of the pipes are filled up from the tide water,” he said. “You’ve got pipes and ditches that just don’t have capacity.”

“After Irma they got 9.5 inches of rain in one day and there was very significant flooding that happened in Satellite Beach and over in Melbourne as well,” Evans said. “When you’re sitting on an island, there’s just nowhere for the water to go when it rains really heavily. With every increment of sea level rise, it just makes that problem worse.”

Another issue: Wastewater

At many sites across the state, canals that collect and carry stormwater are increasingly experiencing higher water levels because rising sea levels prevent them from draining as effectively, Evans said.

Stormwater can also overwhelm systems local governments have set up to treat and dispose of wastewater being flushed from homes.

Flooding rainfall and related rising groundwater infiltrates damaged and cracked older pipes in the yards of homes connected to the wastewater systems and overwhelms lift stations that pump the wastewater to treatment plants.

“That infrastructure on private property that isn’t maintained whatsoever is contributing to the problem,” said Brad Blais, an environmental engineer who lives in Volusia County.

Many utilities in Florida experienced wastewater releases after Hurricane Irma and the continued heavy rain in the weeks after the storm, between power outages and the huge influx of stormwater.

Florida Department of Environmental Protection reports show nearly 100 million gallons or more of sewage and treated or partially treated wastewater overflowed at utility plants across the state during or immediately after Irma. More than 500 accidental releases were reported to the department by Sept. 20, and another 240 occurred over the next four weeks.

Miami Beach at ‘tip of the spear’

For many in South Florida, sea level rise has long since morphed from theory to reality, and officials there have had no choice but to take the lead in protecting and improving the infrastructure in their communities.

Daniel Kreeger, executive director of a group called the Association of Climate Change Officers, tells of returning to his boyhood home in Miami Beach after a long time away.

“My parents’ whole neighborhood was underwater,” he said. “I said to my mom, ‘You must have had a heck of a storm,’ and she said, ‘No, just a high tide.’ ”

The visit had a profound impact.

“This is the sort of stuff that will destroy a community,” Kreeger said.

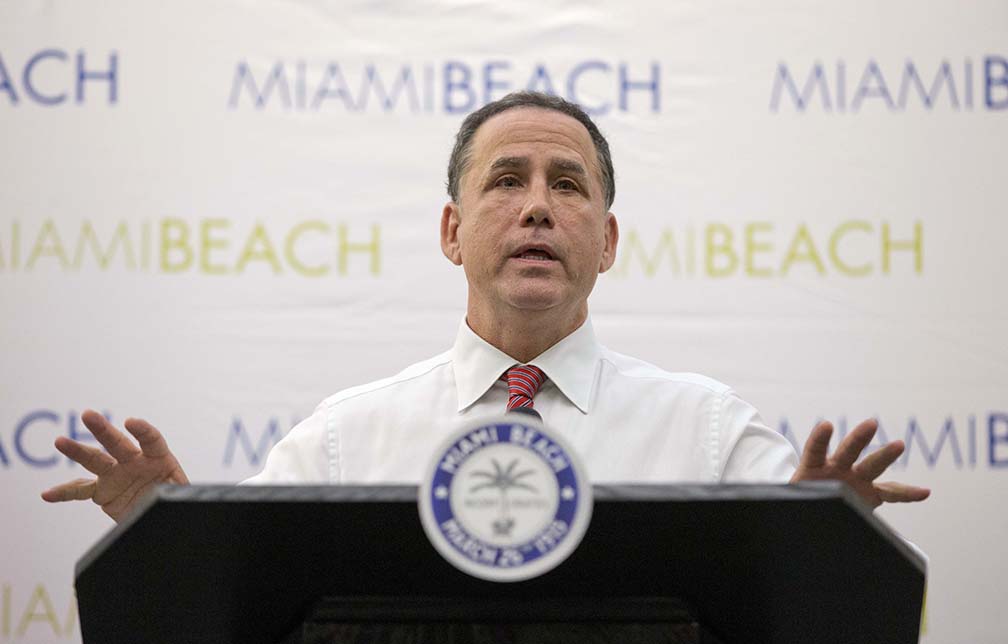

Philip Levine, a Democratic candidate for governor in 2018 and the just-departed mayor of Miami Beach, campaigned once from a kayak on a busy city thoroughfare. He said he came into office in 2013 knowing he had to act.

“You can debate climate change and sea level rise. We don’t do that; we get things done,” Levine said shortly before leaving office Nov. 1 to launch his gubernatorial campaign.

He knows his city is at the tip of the spear where sea level rise is concerned.

“We’re going to have to write the book as we go along,” Levine said. “We’re going to make lots of mistakes, but the one mistake we’re not going to make is failing to do anything.”

Levine got the city government to go along with committing to spend $500 million on armoring Miami Beach against sea level rise. To do so, stormwater fees were increased. About $100 million has been committed so far toward purchasing bonds for construction.

“When people protest, I ask, ‘Do you want to live in Atlantis?’ I think it’s a worthy investment to protect $30 billion in real estate and the lives of residents and friends,” he said.

One project underway in Miami Beach is an effort to move away from gravity-reliant drainage systems. Officials have begun installing expensive pumps designed to push water rushing into the city from formerly efficient outflow pipes back out to sea. Levine said the new systems are being fixed with filtration devices that help prevent debris from flowing out to sea with the pumped water.

Panhandle slow to react

In wealthy Miami Beach, raising roads and installing pipes to remove encroaching water might prove successful. Another major Florida city, Tampa, plans to spend $250 million during the next 30 years rebuilding its stormwater system.

But in places like Satellite Beach, Cedar Key or numerous other communities, finding the money to remove stormwater from areas newly susceptible to flooding could prove daunting.

Another coastal municipality, Northwest Florida’s Destin, has committed to spending $3.6 million on a stormwater program upgrade, according to city spokesman Doug Rainer. The new piping is designed to better dissipate water, he said, and clean what is being sent back to the Choctawhatchee Bay.

Eight counties along the Gulf of Mexico in Northwest Florida — Escambia, Santa Rosa, Okaloosa, Walton, Bay, Gulf, Franklin and Wakulla — have only this year received the first infusion of what will be a $1.2 billion total payout from British Petroleum by 2033 as part of a legal settlement resulting from the 2010 Deepwater Horizon oil spill.

Many Panhandle leaders, including Okaloosa County Commissioner Nathan Boyles, have argued that a significant portion of the funds, earmarked for economic development and diversification, should be spent to improve regional infrastructure.

But Bill Williams, the Restore Act coordinator for Walton County, said through all the infrastructure improvement discussion, he hasn’t heard anyone mention spending to gird against sea level rise.

Boyles said he’s not sure that even with the BP money, bringing sea level rise into Northwest Florida’s infrastructure equation makes financial sense.

“I think the reality is the basic immediacy of fixing what we have outweighs the need to plan for speculative future needs,” he said.

For much of Northwest Florida, sea level rise remains a nebulous future phantom. Part of the reason the region has moved more slowly toward facing rising seas is political. Much of the western Panhandle is deeply conservative, and conservatives, following the lead of officials such as Gov. Scott, have tended to be more skeptical about climate change.

Kreeger said, “Rome wasn’t built in a day,” adding that Northwest Florida is lucky to be a region with numerous military bases.

The Department of Defense, Kreeger said, is serious about the threats rising water poses to its facilities.

Levine, who likes to say “I kinda got floated into office” in Miami Beach, also launched plans to raise 105 miles of roadway in the city “making them significantly higher.”

Evans, the DeLand professor, believes more governments will be prompted to move on sea level rise when water begins impacting transportation.

“When there’s a big king tide, and there’s water in the road, that’s typically when governments start to plan,” Evans said. “People ask, why is there water in the street? Oh, it’s the tide coming up?”

Transportation infrastructure

The Florida Department of Transportation hasn’t taken a firm stance on sea level rise. It has, however, worked with the University of Florida to create what spokesman Ian Satter called “a decision support tool.”

UF’s Geoplan Center tool “provides a better understanding of the vulnerability of transportation infrastructure to sea level change,” Satter said.

Evans and others in his line of work also use the Geoplan. It provides a way to map where roads will be most vulnerable in varying sea level rise scenarios.

“You get to just 9 inches of sea level rise in the Keys and we have pretty significant impacts on the roads,” Evans said.

A sea level rise vulnerability assessment published in February by Sarasota County found more than 40 segments of county, state and federal highways could be affected under a worst-case scenario for 2100, including a section of Interstate 75.

An earlier study, by the Southwest Florida Regional Planning Council, concluded that 27 percent of the major roads in the southeastern United States are built at or below four feet in elevation, as well as 72 percent of the ports in the region, “a level within the range of worst case projections for relative sea level rise in this region in this century.” The study also stated that more than half of the major highways in the region, almost half the rail miles, 29 airports and virtually all the ports are below 23 feet in elevation, and “subject to flooding and damage due to hurricane storm surge.”

Meret Wilson, a long-time Ormond Beach resident, travels to nearby Tomoka State Park several times a week and thinks coastal flooding events are putting the road north of the park under water more often than they used to.

“The last three years we have been having more flooding,” Wilson said. The Tomoka River gets pushed up by high tides and covers the low-lying Beach Street north of the park.

Wilson said she sees it “almost consistently” during the full moons in the spring and fall. After Hurricane Matthew, Beach Street was closed across a marsh on the north side of the park for a week. After Irma, and during the fall high tides, which happened to coincide with Daytona Beach’s annual Biketoberfest, she said the flooding was the “worst ever.”

Kathryn Frank, an assistant professor in the department of urban and regional planning at the University of Florida, has worked to document sea level rise on both coasts, in Flagler, St. Johns and Levy counties.

After Hurricane Hermine swept a 7.5-foot storm surge into Cedar Key, between the erosion and the floodwaters, Frank found sections of road that had been lifted up. The island archipelago on Florida’s Gulf Coast has some low-lying areas and some higher areas.

The town itself “won’t be inundated for a long time,” said Frank, but rising water “is going to fragment in between the hills.”

As roadways leading in and out of the town begin to flood more often in the low-lying areas, she said, “there are going to become areas that kind of cut things off.”

East of town, in a developing rural area, saltwater marshes have been moving closer to the main highway.

“The marshes are up to the highway already,” Frank said. “It’s just going to keep moving in.”

“As sea level rise continues, it becomes more common and then it starts happening in more places,” she added. “Sea level rise and the storms work together to create more frequent hazards and more severe hazards.”

‘It is now a mature effort’

Kreeger, whose Association of Climate Change Officers is dedicated to building a workforce capable of developing strategies to ensure institutions can survive in a changing world, is a staunch advocate of local governments initiating steps to address sea level rise.

He’s dismissive of both Scott and President Donald Trump as advocates for needed change in thinking.

“If your community is going underwater and your governor is saying, ‘by the way, it’s not happening and my staff isn’t allowed to use the words ...’ communities have to act,” Kreeger said.

Trump, who has said he wants to spend $1 trillion on infrastructure, has taken action to strip regulations that would require proper care be taken to build secure structures like roads and bridges in areas susceptible to climate change.

The president is “actually going to be a blessing” in the battle against sea level rise, Kreeger said. “He’s going to compel local and state leaders to step up most vigorously, which they should have done in the first place.”

The success of the grassroots movement to act now is exemplified by the Southeast Florida Regional Climate Change Compact.

In 2009, the counties of Miami-Dade, Broward, Monroe and Palm Beach banded together to create the compact, which represents nearly 6 million Floridians in a region whose gross domestic product, or GDP, exceeds all but about eight states, Kreeger said. It is the largest regional climate group in the country and claims 35 municipalities as members.

The group has developed a Regional Climate Action Plan with 110 recommendations of ways to make Southeast Florida more resilient to climate change and sea level rise. Its website trumpets steps being taken toward leveraging state and federal funding to mitigate the impacts of climate change and sea level rise.

Several municipalities within the compact’s boundaries are taking steps similar to those of Miami Beach to armor areas impacted or threatened by sea level rise.

“It is now a mature effort,” Kreeger said.

Daytona Beach News-Journal Dinah reporter Voyles Pulver contributed to this report.