Redemption:

Abused and taunted, young Mark turns to drugs, alcohol, gang

In an emergency, call 911

Drifting toward death, Mark has a fateful encounter

As her son’s criminal record lengthened and Gonsalves served sentences at the Adult Correctional Institutions and elsewhere that eventually totaled a dozen years, Sara Rose waited tables, tended bar, owned a produce business and served as an accountant. She was good with numbers and good to her son, who sometimes stayed with her. Good with finances, she bought a house.

In October 1991, one of Gonsalves’ Hillside Posse buddies, Brent Davis, 20, was killed in New Bedford in what police called a drug-related turf war. Gonsalves was selling drugs in Virginia when his mother phoned to tell him that his good friend was dead.

“It hurt, but I don’t remember crying,” he said. “It was like my emotions were turned off. I had no emotions.”

Perhaps, he would later think, the traumas he'd endured had desensitized him. The childhood abuse. The blows to the skull during fights. The car crash when he was about 3 in which his head had struck the windshield with enough force to shatter the glass.

Between prison terms in the 1990s, Gonsalves had fathered four children, with two different women. He did not know and would not learn until much later that he had a fifth child: a daughter born of a hookup with a teenage girl before he left Florida in 1987 who had been put up for adoption and raised by a family in Texas.

By 2005, when Gonsalves was 33, it was all becoming too much.

“I was ashamed of myself,” he said.

For the second time in his life, he attempted suicide, with an overdose of pills.

Stories that inspire. Coverage that informs. Investigations that affect change. This is real news just when it's needed most. Subscribe today.

Subscribe

'God, please just let me live': Redemption proves elusive

A rising sense of purpose, and an emotional reunion

At Amos House, Gonsalves used the 90-day program “to develop the skills and the resources to remain drug- and alcohol-free,” Amos president and CEO Eileen Hayes said.

He also became “a diligent student in our culinary program,” Hayes said, “always willing to go the extra mile to help out in our soup kitchen as well as in our catering events. As if his plate was not full enough, Mark enrolled in college classes with the Reentry Campus.”

That came thanks to James Monteiro, who manages Reentry Campus, which provides presently and previously incarcerated people “an affordable pathway to accredited post-secondary educations and certification programs.” Education and training for good jobs, that is. Gonsalves today is enrolled in college-preparation courses at Roger Williams University. One of his ambitions is to become a social worker or counselor.

Setting and meeting goals was critical, and Gonsalves wrote his in a notebook, which he has kept to this day. Among his short-term goals: "Stay clean — 1 day at a time," "make meetings," "volunteer as much as possible," "enroll in college courses" and "last but by no means least: see kids regularly."

On his long-term list: "Stay clean — 1 day at a time," "continue meetings regularly," "complete schooling" and "last but by no means least: be a simple man."

And other people have played leading roles in the rise of Mark Gonsalves. A psychiatrist, a therapist and friends old and new.

Anthony Thigpen — like Monteiro, a recovered addict who spent years in prison before his own redemption — stands center stage. A community health worker with the Transitions Clinic at the Lifespan Community Health Institute in South Providence, Thigpen connected Gonsalves to first-rate mental and physical health care. He helped arrange federal disability payments. He listened. He encouraged. He took Gonsalves’ call at any hour, and still will.

Like Monteiro, he provided living testament to the possible.

Eventually, “Mark graduated from our program and moved to a sober house with a part-time job with Amos House on an extended internship funded through a Department of Labor grant,” said Hayes. Today, he is also employed at a major concert venue in southern New England, with responsibility for the personal security of the guest artists. He leads a Narcotics Anonymous group at Amos House. He has banked some of his income and is saving for a truck. He intends to find his own apartment.

Monteiro met him at a Narcotics Anonymous meeting. “I heard him sharing and I liked his message,” Monteiro said. “Usually, you can see when somebody’s talking just from remote memory and when somebody’s actually talking from their heart. The way Mark conveys his story, he’s speaking from experience. That’s from his heart. And that’s what stood out for me.

“The change that’s happening in him is genuine.”

Gonsalves, now 47, made amends to his children.

Learning through a Facebook connection and a phone call that he was the biological father of Ashlea, a 30-year-old woman living in Texas, Gonsalves had reached out to her before his suicide attempt. A registered nurse — and now mother of a toddler, making Gonsalves a grandfather — she flew to Rhode Island to meet him in 2015. They have remained in close contact since. Gonsalves also has developed a relationship with Marcus, his 24-year-old son who lives in Maryland.

Geography provided better opportunity for rapprochement with his three children who live locally: Mark, 27, a Providence resident who delivers pizzas; Khayla, 24, a Dunkin' Donuts employee who lives with her mother in Portsmouth; and Jhamal, 22, a Portsmouth resident who works at Newport Shipyard and is a rising star on the New England motocross circuit.

Khayla and Jhamal discussed their dad recently at their mother’s house. Gonsalves was present.

“I feel like since Nana passed away, our relationship grew really a lot stronger,” Khayla said.

“We talk almost every day and hang out more. It’s definitely a better relationship.”

“The same here, too,” said Jhamal. “Growing up, I didn’t even really talk to him that much. Now our bond is quite different.”

On his regular trips to Aquidneck Island, Gonsalves stops by the Dunkin' Donuts where his daughter works, sometimes passing hours there. Khayla lives with Type 1 diabetes, a potentially life-threatening disease requiring daily insulin that was diagnosed when she went into a diabetic coma several years ago. She finds support in her father, she said.

Gonsalves also sees Jhamal on Aquidneck Island — and at his son’s motocross races at tracks around New England. Fascinated by cars and motorcycles from a young age, like his dad, Jhamal was the fall 2018 NESC Motocross champion in the 450C category. It was his first year of formally racing.

“I’m so proud of them,” Gonsalves said.

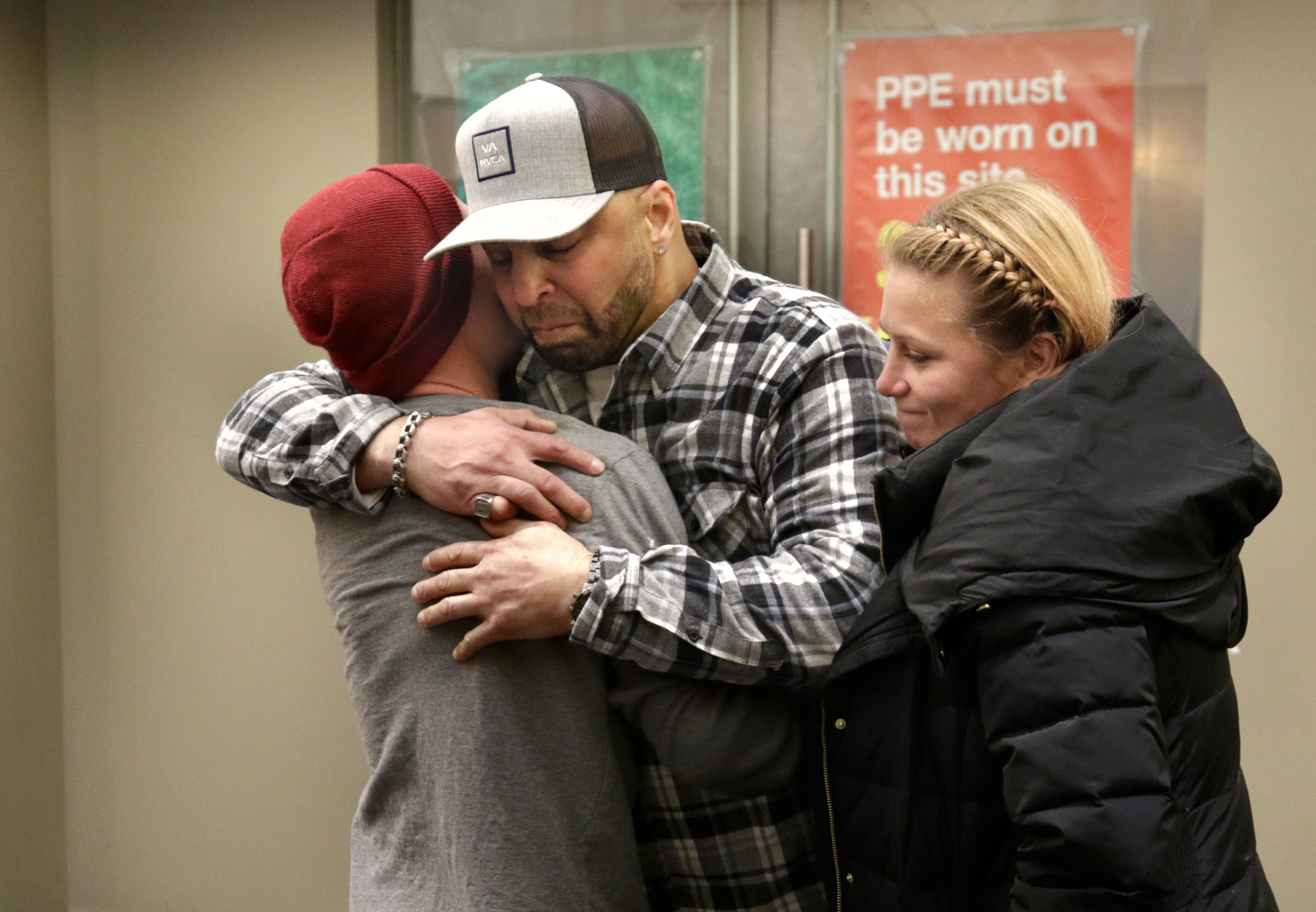

This being Rhode Island, with its negligible degrees of separation, it was perhaps inevitable that Ashley Brophy learned from a friend of a friend at Rhode Island Hospital that Gonsalves had lived. But she, Jeff Nichols and Dave Poland had not seen him since June 26, 2015.

Poland found Gonsalves on Facebook in September 2018, and following that, Brophy spoke with him at length by phone. The three boaters and the man they saved wanted to see each other again. They reunited on Dec. 4 at The Providence Journal.

Tears flowed. Hugs were exchanged, stories told; luck and the hand of a higher power were among the topics. The memory of Sara Rose Gonsalves, too.

After an hour or so, the four went to a nearby restaurant for dinner. There, they posed for a photograph that Brophy posted on her Facebook page.

“So after 3 years a long awaited reunion happened,” she wrote. “3 summers ago Dave Poland Jeff Nichols and i found a man floating almost lifeless under the Newport Bridge. We had been in contact and wanted to meet him and tonight we did. I didn’t quite know what to expect or feel. But it was awesome.

“He is actually a very inspiring and genuine man who has turned his life around and is using his second chance to help others. It was a super humbling experience. Mark, it was great meeting you and look forward to a new friendship among all of us. Keep up the positivity and moving forward. Great night tonight. God is good.”

Mark Gonsalves lives with daily pain from the injuries he suffered in his fall, but he manages. He carries sadness, at the harm he caused others years ago, and for the manner and year in which his mother died.

“She never got to see me get it, finally,” he said. “To become a man.”

A simple kind of man, as Lynyrd Skynyrd sang.

After a visit last autumn to Goat Island, where he looked up at the Pell Bridge, rising over a sparking Bay, Gonsalves reflected on why he, a person who the odds say should not be here, is.

“It’s all making sense to me now,” he said. “I believe in faith and God’s plan.”