Hidden and pervasive

Lindsey Cooper sits in one of Identity Dance Company's studios, with a verse from Psalm 139:14 is painted along the wall, "I am fearfully and wonderfully made." Cooper says that she wants her dancers to understand that they were made with everything they need for this life. [Dana Sparks/The Register-Guard]

Raising awareness and educating the community key to combating sex trafficking in Lane County

Lindsey Cooper walks down a hallway, past a paper plate Pac-Man on the wall, under life-size cardboard Nintendo controllers and into her dance studio's Blue Room.

As she opens the door, a horde of promising 5- to 7-year-old dancers gasp and rush through the wood-paneled studio with a wall of mirrors and a graffiti mural to her side.

“Miss Lindsey!” they shout out to her as they grab at her and she gives several rounds of high-fives.

After the giggles calm, she gathers them in a circle for a quick chat as they finish their second day of summer dance camp. They talk about the new dance they learned, how much they love their instructor, Miss Francesca, and how they are enjoying their video game-themed camp.

The dance campers are young, but Cooper still takes the time to talk about important life lessons and how dance can help them.

“In order to level up, sometimes we go through something hard,” Cooper explained. “But if we get back up and keep playing, we get stronger.”

These life lessons aren't just for her dancers. Cooper aims to live by those words, too.

Cooper is a vibrant and strong mother of three, passionate dancer and sex trafficking survivor.

Cooper's experience in the pervasive sex trafficking industry — when a person engages in a commercial sex act by force, threats of force, fraud, coercion or any combination, as defined by the U.S. State Department — unfortunately is not unique or rare, but she is one of the fortunate ones who has escaped the emotional and physical bonds of her experience.

And although pain and suffering may be a large part of her past, faith and hope are an even bigger part of her future.

It happens everywhere

Sex trafficking is a silent problem, its prevalence aided by a fractured system of welfare services and lack of public awareness. It hides in plain sight, debilitating the efforts to help trafficking survivors rebuild their lives at all levels — from international initiatives to a local county task force of agency officials and community members.

“Trafficking is a problem everywhere,” said Eugene police Detective Curtis Newell. “Our community is not exempt from that problem.”

The U.S. Trafficking Victims Protection Act of 2000 provides the tools to combat trafficking in persons both worldwide and domestically, creating the State Department's Office to Monitor and Combat Trafficking in Persons and giving the government the power to combat trafficking by reauthorizing certain federal programs.

The act addresses “severe forms of trafficking in persons,” including labor, involuntary servitude, debt slavery, debt bondage, sex trafficking or slavery. It defines sex trafficking in particular as a commercial sex act induced by force, fraud or coercion, or when the person induced to perform such an act is not yet 18 years old. Despite its name, a sex trafficking victim doesn’t need to be physically transported from one location to another for the crime to fall within the definitions of human trafficking.

An important takeaway from the TIP Office's 2018 annual Trafficking in Persons Report is that while human trafficking happens globally, it also happens at a local level.

“People have a disconnect because they don't want to believe it could ever happen in their neighborhood,” international sex trafficking expert Cyndi Romine said. “They want to believe it can only happen in a big area. The truth is, it happens in every village, every small town and every large town. It happens everywhere, all the time.”

In Oregon, according to the National Human Trafficking website, 135 human trafficking cases were reported in 2018 — 101 of those involved sex trafficking.

Those 135 cases may not seem significant, but much like its counterparts sexual assault and domestic violence, sex trafficking pervasiveness is hidden because it is largely underreported.

Reporting is a challenge for multiple reasons. Each sex trafficking case can present itself differently — trafficking situations can be disguised as different crimes, such as domestic violence, stalking, sexual assault or exploitation. Victims often don't realize they're involved in a trafficking situation or that they are victims. Victims also may feel shame or guilt about telling anyone about what is happening to them. When they do identify as victims, they can make contact with one of a variety of agencies, depending on the help they are seeking.

That lack of reporting in Lane County and across the nation leaves law enforcement or welfare services without sufficient data to make informed decisions on how to combat sex trafficking.

Locally, officials are working to address that void by developing a countywide system to consistently and uniformly collect data at all welfare agencies that interact or could make contact with girls, boys, men and woman who may be sex trafficking victims, said Sarah Stewart, executive director of Kids FIRST, a Lane County child advocacy group.

"There are a number of organizations like (Kids FIRST) that are spending a lot of money and time tracking this information, and even then it's hard to find,” Stewart said. “We're working on making sure that the groups that we're working with are tracking data in a similar way. If we're all tracking different data, then we're not getting substantive samples.”

Despite lack of data, Lane County is creating programs and resources for survivors to help combat and prevent sex trafficking in the area. Stewart and Eugene police's Newell are members of the Lane County Commercial Sexual Exploitation of Children Multidisciplinary Team, or CSEC MDT. The team is a collaborative effort between various local agencies that serves as a response team for sex trafficking and to provide survivors and victims with the best possible resources.

Anyone can be a trafficker, but more importantly anyone can be a victim, said the CSEC team's lead coordinator, Tamara LeRoy, who also serves as the trafficking intervention coordinator for Sexual Assault Support Services, or SASS.

Victims may be of any gender identity, age, nationality or background. Marginalized and underrepresented communities — people of color, indigenous people, people with different sexual orientations or gender identities and those who suffer from mental health issues — have a higher risk of being trafficked.

“If you’re interacting with a human population, you’re interacting with a trafficked population,” LeRoy explained while talking about the magnitude of the sex trafficking industry. “It happens here and at shocking rates. If you think that you haven't directly come in contact with somebody who's been trafficked, you're kidding yourself.”

When Newell participates in community education sessions, he talks about how sex trafficking does not always look like how it’s portrayed on television or movies.

Those media portrayals can add to the confusion because trafficking scenarios often are sensationalized in pop culture, depicting stereotypes of black men trafficking young, promiscuous women. In reality, LeRoy said, trafficking situations can seem much more “normalized.”

“People assume that (victims) are already caught up in drugs and a promiscuous lifestyle, but they can be low-risk and come from good families,” she said.

How are victims drawn in?

Newell is one of four detectives on a special investigations team that handles sex trafficking cases, running sting and undercover operations to gain access to victims and catch traffickers.

Sex traffickers look for vulnerabilities in individuals and actively exploit them, LeRoy said.

In Cooper's case, the Eugene sex trafficking victim and now the owner of Identity Dance Company in Springfield, she met the man more than 15 years ago who would be her purchaser at a Eugene restaurant. Cooper thought she was meeting about a job opportunity set up by her roommate, she said.

“It can happen right under our noses, and it can look normal,” Cooper said. “I mean, we looked like we were having a business lunch.”

Once victims are caught in the lifestyle, sex traffickers keep them in the industry by using control and manipulation, including violence, threats, lies, drug abuse and debt bondage. Sometimes victims are forced into non-consensual drug use in order to create a drug dependence.

For the traffickers, there's money at stake. Sex trafficking is a financial-based industry, although sex trafficking can be an exchange of anything of value.

It's an industry that, sex trafficking expert Romine says, brings in more than $2 billion a year. One trafficker running four to five victims can make $200,000 to $300,000 tax-free, said Romine, the founder and president of Called to Rescue, an international nonprofit organization that helps children who are missing, abused or trafficked.

As a 21-year-old who was just fired from two jobs and rejected from several dance opportunities, Cooper was looking for a fresh start. So, when her roommate pitched a dream job offer that would take Cooper out of state, earn her a high wage and give her the opportunity to experience luxury, Cooper said yes.

Cooper felt like she had nothing, which made the promise of the job seem even more amazing, but the situation changed quickly. The 34-year-old man who was supposed to be her boss and became who she thought of as her boyfriend, turned out to be her purchaser, Cooper said. She said he groomed, coerced and abused her more than 4 1/2 months.

The man had Cooper complete paperwork and laundry, tasks he'd outlined in her job contract, Cooper said, but she was also coerced into sexual acts and made to believe that the man loved her.

When she confronted her roommate about the situation after having sex with her “boss,” Cooper said her roommate told her not to worry, “it’s just part of the deal,” and that Cooper should remember all of the great things she was getting out of it and stay. Cooper said she went along with it because she felt she had to.

“I was scared because I had seen him get really angry and frustrated at me,” Cooper said. “So I just did what it took for him to be happy. And that included sexual gratification, in the moment I realized that is why I was there. That’s why I was hired.”

A young girlfriend with an older boyfriend is a very common trafficking scenario, one where the victim might be tricked into thinking they love their trafficker, LeRoy and Newell said. These types of scenarios, they said, can take a turn after the trafficker manipulates a victim into a dependent role with them, called grooming.

Traffickers groom potential victims by providing them drugs, alcohol and other items of value. LeRoy said traffickers will take the time, even if it means months, to develop relationships and build trust with potential victims to gain control of them. From there, it becomes easier for traffickers to trick their victims and take control of many aspects in their life, or even threaten their friends and family if they don't comply.

For Cooper, she said the man who purchased and exploited her also provided everything for her. He also rarely left her alone. While he never sold her to anyone else, let alone let her talk or interact with anyone else, he continued to pay her roommate the money Cooper earned, she said. Cooper said she thought it was to pay her rent, though she later found out that her roommate had rented out her room while she was away, without her knowledge or permission.

During her time with the man, she said she never saw or was in control of the money she earned. The man would sometimes give her money for laundry or small snacks but that was it, Cooper said. She wasn’t aware of how much money she made, only that the man made wire transfers into her account back home, she said.

Cooper's time with the man ended abruptly, a little more than four months into her six-month "contract," the man gave her a plane ticket to Eugene.

“He sent me home early," Cooper said. "And to me I think that that was so miraculous, and saved me from a lot more heartache and just being around him.”

Beyond a situation that appears as people dating, there are many different ways a person can be trafficked, including through their own family. Newell said he’s seen cases where three generations of family members are involved in the trafficking of one or more members of their family, including children.

There is no “one size fits all” situation when it comes to sex trafficking.

“Generally, survivors aren't chained up or locked in at night,” LeRoy said. “The ties that they have to their traffickers are largely traumatic and emotional.”

Because sex trafficking can look like a relationship, victims of sex trafficking struggle to identify as victims at all. According to Newell, the amount of psychological and trauma bonding that happens between a trafficker and a victim causes the victim to be unaware of what is really happening.

“The attachment is marked by a shift in internal reality, whereby the victim begins to lose her sense of self, adopts the worldview of the abuser, and takes responsibility for the abuse,” said Amanda Swanson, the trafficking coordinator for the Oregon Department of Justice.

I-5: Corridor of broken dreams

While it can happen anywhere, there are specific places in the U.S. that are more prone to sex trafficking because of ease of access, not because of population.

The Interstate 5 corridor, a prolific area for sex trafficking, is 1,381.29 miles long from Washington's Canadian border to California's Mexican border. It intersects other major interstates, including I-90 in Seattle, I-84 in Portland and I-10 out of Los Angeles, offering easy ways for traffickers to gain access to potential victims and move them if they want. It also makes every city, like Portland, and towns, like Junction City, on the corridor susceptible.

“Eugene is on that corridor,” Romine said. “So any city anywhere along that corridor is targeted and there's a lot of kids that go missing in it. Eugene's a really big problem as well."

Law enforcement often sees traffickers move victims in a circuit or route within the state or county, using I-5 regularly, Newell said. But he noted victims can be trafficked in the place they live and never be relocated by their trafficker.

Locally, Eugene Police Department is in a position to provide the most resources to sex trafficking cases, said Detective Newell. He and the other CSEC team members can devote their resources to take the lead in local trafficking investigations.

Based on his experience in successful sex trafficking investigations, Newell has developed an investigative model for mid-sized police departments, including Eugene's, that includes surveillance techniques and sting operations.

“Sex trafficking is happening daily,” Newell said. “It's just a matter of coordination for our team to go and set up an investigation where we can focus on specific cases that we're aware of or keep tabs on the activity that's happening around our community.”

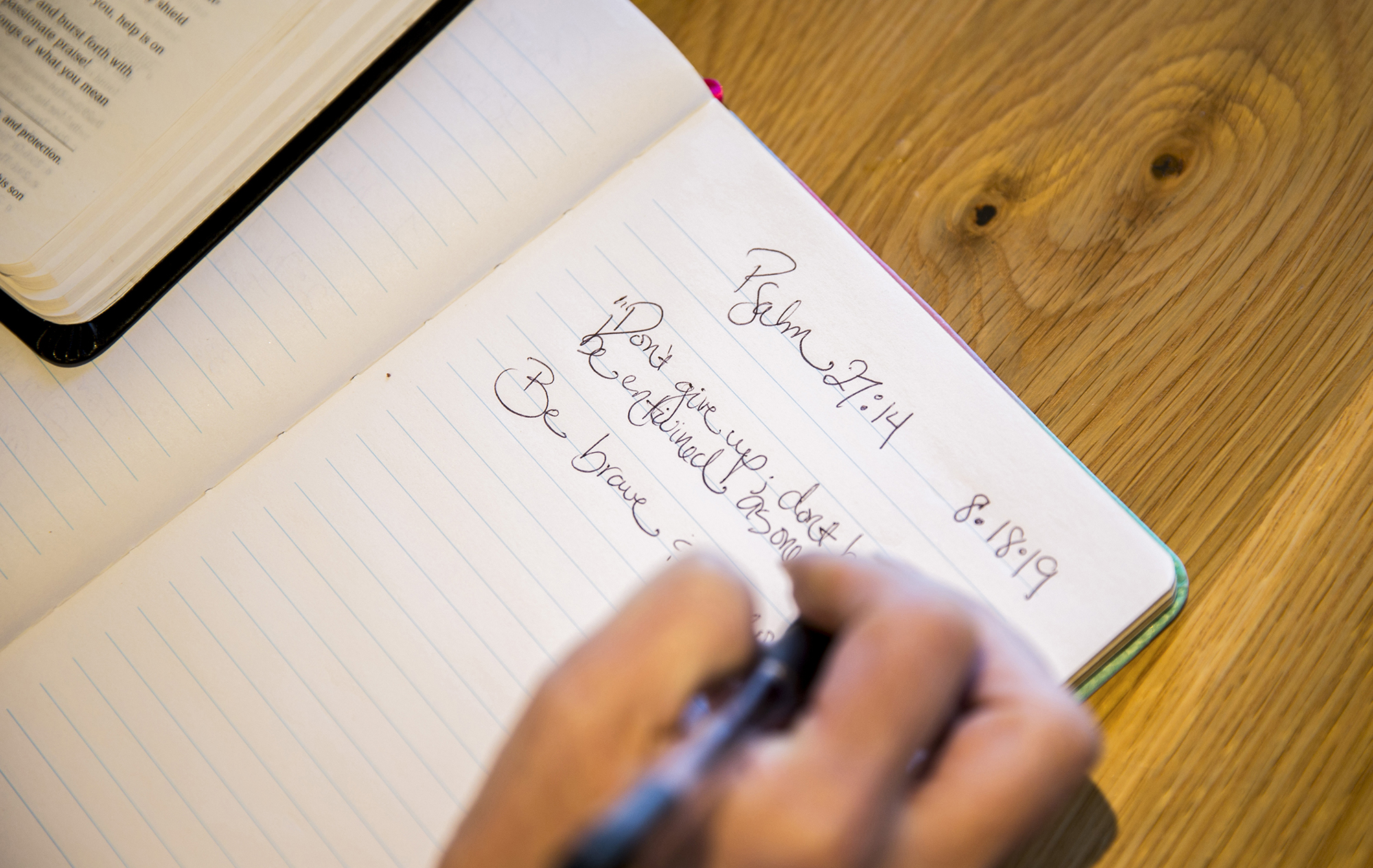

Never give up

After leaving her dance studio's Blue Room, Cooper walks into the Red Room where the 8- to 12-year-old campers practice adding acrobatic movements into dance.

Just like before, she rounds the campers up to talk. They gather around on the floor, a large graffiti mural beside them reading “You are fearfully and wonderfully made.”

The words were picked by Cooper, from Psalm 139:14, in hopes that her dancers will know they were created with everything they need to survive in this lifetime.

“What was yesterday's word of the day,” Cooper asks.

“Suffering,” the children say in unison.

“That’s right,” Cooper says. “Sometimes in life we suffer through things that are painful. But then we have today’s word, which was … ?”

“Perseverance,” the dancers shout.

“And what does that mean?” Cooper asks.

“Never give up!”

“That’s right,” Cooper says proudly. “We never, ever give up."

This project was developed by Destiny Alvarez and Dana Sparks, Charles Snowden Excellence in Journalism reporting and multimedia interns for The Register-Guard. Follow Destiny on Twitter @DesJAlvarez or email destinyjalvarez@gmail.com. Follow Dana on Twitter @danamsparks or email dsparks@registerguard.com.