Predator

Pipeline

Two women separately accused University of South Florida football player LaDarrius Jackson of sexual assault in 2017, saying the 6-foot-4, 250-pound defensive end forced himself on them in their own homes.

Police arrested Jackson twice in two weeks on charges of sexual battery and false imprisonment. He pleaded not guilty and posted bond while awaiting trial.

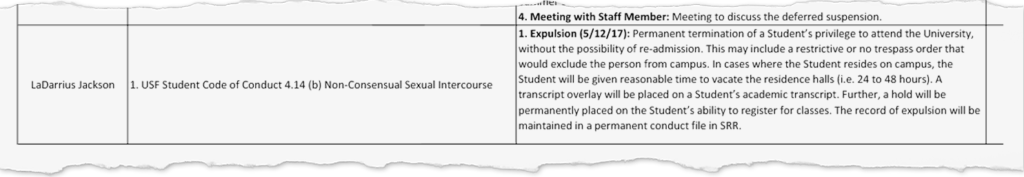

The university also opened a student conduct case against the then-22-year-old junior. It determined he violated its policy against “non-consensual sexual intercourse” and expelled him.

Yet one year later, Jackson played before a crowd of nearly 30,000 fans as Tennessee State University took on Vanderbilt in Nashville. Jackson played six games for TSU in 2018, transferring there while facing the possibility of decades behind bars in Florida.

That his expulsion and ongoing criminal case posed no obstacle to his collegiate football career isn’t unusual.

College athletes can lose their NCAA eligibility in numerous ways, but sexual assault is not one of them. Even when facing or convicted of criminal charges, even when suspended or expelled from school, NCAA rules allow them to transfer elsewhere and keep playing.

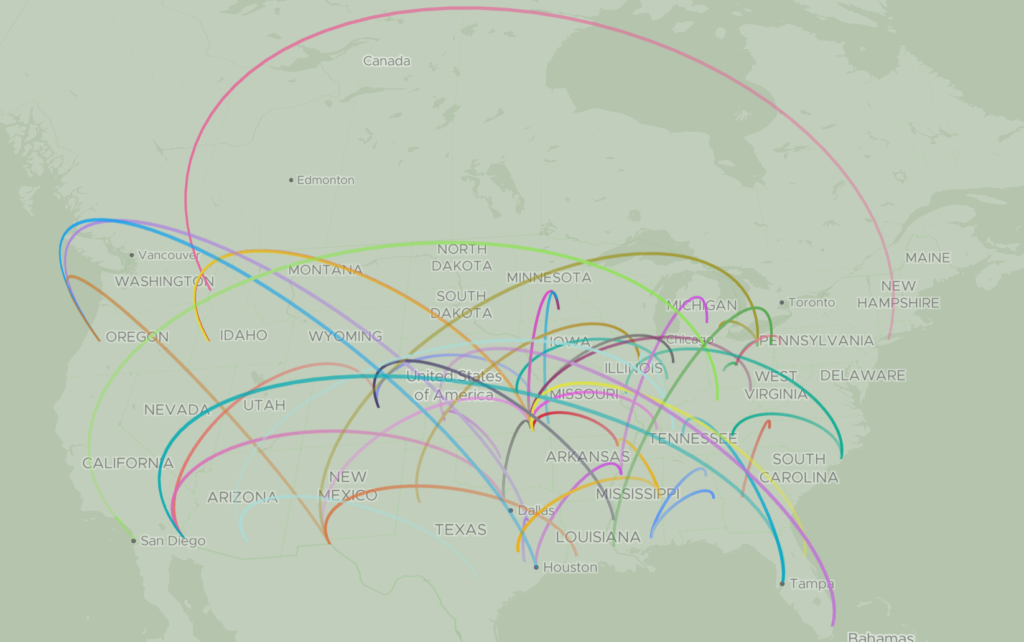

An investigation by the USA TODAY Network identified at least 28 current and former athletes since 2014 who transferred to NCAA schools despite being administratively disciplined for a sexual offense at another college. It found an additional five who continued playing after being convicted or disciplined for such offenses through the courts.

In addition to Jackson, who through his attorney declined to comment, these players include a pair of receivers from University of Oregon and Ohio State, a kicker from University of Kentucky, a defensive end from Purdue, and an All-American sprinter now at Texas Tech who helped the track team win its first-ever national championship in June.

The NCAA notoriously metes out punishments to student athletes for bad grades, smoking marijuana or accepting money and free meals. But nowhere in its 440-page Division I rulebook does it cite penalties for sexual, violent or criminal misconduct. And unlike the pro leagues, the NCAA has no personal conduct policy and no specific penalties for those who commit sexual assault.

The NCAA’s highest governance body, a group of university presidents, chancellors and athletic directors known as the Board of Governors, is well aware of the issue. But it has resisted calls by eight U.S. senators and its own study commission to fix it.

The NCAA declined to comment for this story.

The list of 33 players identified by the news organization — which operates 261 daily newspapers — is by no means an exhaustive count.

The USA TODAY Network filed public records requests for campus disciplinary records at 226 public universities in the NCAA’s highest echelon, Division I. It also combed through hundreds of pages of police reports, court filings and other documents, and spoke with dozens of school officials, victims, lawyers, researchers and advocates.

But 5 of every 6 universities refused to provide the records, even though federal law gives them explicit permission to do so. The disciplinary records from the schools that complied revealed the names of hundreds of students found responsible for sexual offenses — many of whom the USA TODAY Network identified as athletes who transferred and continued playing afterward.

Among the investigation’s other findings:

- No matter if schools suspend, dismiss or expel athletes for sexual misconduct, NCAA rules provide avenues for them to return to the field on a new team within a year and sometimes immediately.

- Approached by the USA TODAY Network about athletes on their rosters previously disciplined for sexual misconduct, many athletic departments claimed no knowledge of the past offenses. Most schools lack formal background check policies, instead relying on former coaches’ words and a questionnaire called a “transfer tracer” that often fails to capture past disciplinary problems.

- Players regularly exploit the NCAA’s own loopholes to circumvent its one meaningful penalty for those who transfer while suspended or expelled — a year of bench time. Athletes can go to a junior college for a minimum of one semester before returning to a Division I school. Or they can transfer to another NCAA school before the discipline takes effect.

- A handful of the NCAA’s nearly three dozen Division I conferences have adopted their own policies banning athletes with past behavioral problems. But their definitions of culpability vary, and most rely on the honor system — not actual record checks — to verify recruits. Some problematic athletes have slipped through the cracks.

- The records provided by 35 public Division I universities show they disciplined NCAA athletes for sexual misconduct at three times the rate of the general student population since 2014, and football players were disciplined the most. No news organization, university or athletic institution, including the NCAA, has ever done such a comprehensive study of athletes found responsible in campus conduct investigations.

Recent research has shown that a small fraction of students commit a majority of campus sexual assaults. That makes the practice of bringing athletes previously disciplined for sexual assault onto new campuses “an extreme liability,” said John Foubert, a rape prevention expert for the U.S. Army and dean of the Union University education college in Tennessee.

“I think it’s a fundamentally stupid idea,” Foubert said.

Campus disciplinary proceedings often are criticized as unfair toward the accused. Some students have complained that schools violated their due process rights and won favorable rulings in court. U.S. Education Secretary Betsy DeVos is working to allow schools to increase the recommended evidentiary threshold in those cases.

Some also argue that athletes disciplined by their schools are innocent until proven guilty in court and should not be disqualified from competing. However, athletes convicted of sex crimes and registered as sex offenders — including former Air Force football players Jamil Cooks and Anthony Daniels — are also among those who’ve received second chances.

Others criticize colleges for creating the sense of entitlement that can translate into sexually violent behavior. Athletes routinely receive exclusive access to multimillion-dollar facilities, free food, clothing, tutoring, training, medical treatment and equipment, priority registration in classes, full-ride scholarships and even monetary stipends.

If colleges and coaches do not instill in players a sense of responsibility that comes with these privileges, it can set them up to fail, said Laura Finley, a professor of sociology and criminology at Barry University in Florida.

“They are often your most idolized people on campus,” Finley said. “They may be getting preferential treatment by university officials or other people already. They are oftentimes used to doing what they want and being the big man on campus.”

The USA TODAY Network reached out to nearly 100 coaches, athletics directors and athletes for comment for this story. All but two coaches and one athletic director declined interviews. Others provided statements instead, or referred questions to university spokespeople and attorneys. Those sources said their schools scrutinized the players thoroughly, believed they were safe for campus and so far haven’t received subsequent sexual misconduct reports involving them.

Read statements issued by coaches and/or their universities in response to questions from the USA TODAY Network

But that approach may expose universities to what California civil rights attorney John Manly called a “ticking time bomb.” They could be liable for legal damages if the transfers hurt someone there, and in most states, so could administrators and coaches, Manly said.

“If that time bomb goes off while that person’s at school, that university has full liability,” said Manly, who represented victims of Larry Nassar, the former USA Gymnastics and Michigan State University doctor sentenced to prison for sexually abusing young athletes in his care.

Michigan State did, in fact, recruit a troubled athlete who went on to reoffend while playing for the Spartans. In 2016, head football coach Mark Dantonio signed high school standout Auston Robertson despite knowledge of previous accusations of sexual assault by at least two women in his home state of Indiana.

One year later, Robertson was charged with raping one of his MSU teammates’ girlfriends. He was dismissed from the university, pleaded guilty to a lesser charge in 2018 and was sentenced to up to 10 years in prison.

MSU now is embroiled in a lawsuit filed by a former recruiting director, who claims the university wrongly terminated him in part over that case, despite his warnings to Dantonio not to sign Robertson.

For survivors of campus rape, the issue is not one of legal liability or policy consistency. It’s about the moral and ethical implications of reelevating the perpetrators of their traumatic assaults to positions of prominence while leaving the aggrieved to pick up the pieces.

“It blows my mind how transactional it is, and how they don’t think about the consequences for the student body or for the school,” said Daisy Tackett, a former University of Kansas rower who in 2015 reported being raped by a KU football player.

In that case, KU found long snapper Jordan Goldenberg responsible for engaging in “non-consensual sex” with Tackett and sexually harassing another rower in a separate incident, documents show. He was banned from campus, only to resurface on the Indiana State University football team a few months later.

Goldenberg did not respond to multiple phone and social media messages seeking comment.

Indiana State told the USA TODAY Network that only assistant coach Gary Hyman “was aware of Jordan Goldenberg’s student conduct background” at the time. Hyman had previously coached Goldenberg at KU. Once the news of his transfer broke, Indiana State dismissed Goldenberg from the team and suspended Hyman for two days with pay.

Hyman knew Goldenberg got in trouble at KU but didn’t know why or that he had been expelled, he said.

“I deeply regret that I was not more communicative with the limited information I had about Goldenberg,” said Hyman, who is now the University of Texas at San Antonio football team’s special teams coordinator. “At no time, though, was there any deception or ill intent on my part.”

There should have been rules to stop Goldenberg from joining the team in the first place, Tackett said.

“There are probably millions of other people that they could recruit,” Tackett said. “I don’t get why it’s so hard for the NCAA to say, ‘Rape is bad.’”

‘Compromising their values’

Schools are required by federal law to investigate sexual assault allegations involving students, including college athletes. For those found responsible, the highest form of punishment a school can impose — even in the most egregious cases — is expulsion.

But expelled college athletes can simply transfer elsewhere and keep playing.

The NCAA, meanwhile, employs a nearly 60-member enforcement staff to investigate potential violations of amateurism and academic eligibility rules, weighing in on issues like whether players ate too much pasta at a banquet or if a recruit’s father wrongly accepted a razor and shaving cream while on the road.

It has suspended athlete playing privileges for infractions as minor as lying about buying a used mattress from an assistant coach. And it can impose permanent bans for major violations, not only ending players’ college sports careers but jeopardizing their scholarships and chances of going pro.

Many experts criticize the NCAA for placing too much emphasis on minor infractions and not enough on serious misconduct like sexual violence. But one former NCAA investigator noted that schools could solve the problem on their own by refusing to recruit such athletes.

“It’s another example of schools compromising their values to win games and make money,” said Tim Nevius, who led dozens of NCAA rules enforcement cases from 2007 to 2012 and now runs a New York law practice representing college athletes in eligibility issues.

Right now, the USA TODAY Network investigation found, troubled transfers easily gain acceptance at new schools where they can get a fresh start.

For Jackson, the former University of South Florida player accused of rape, he found acceptance in Tennessee.

Jackson was arrested by USF police on May 1, 2017, on charges of sexually assaulting a female student earlier that day. According to her statement in a campus police report, Jackson forcibly pushed her into her room, straddled her on her bed and masturbated on her chest.

A day later, a different female student told the Hillsborough County Sheriff’s Office that Jackson trapped her in the bathroom of her apartment, forcibly removed her clothes and raped her in March.

USF expelled Jackson later that May after he accepted responsibility, according to records obtained by the USA TODAY Network, not contesting the charge and waiving his right to appeal.

The Hillsborough County State Attorney’s Office is prosecuting both criminal cases. Between them, Jackson is charged with three counts of felony sexual battery, two counts of false imprisonment and a count of misdemeanor battery. He pleaded not guilty.

Jackson sat out the 2017 season, but by 2018 he was back on the field in a Tennessee State uniform under head coach Rod Reed.

Tennessee State officials declined to answer questions about Jackson.

University spokesman Emmanuel Freeman said the school “is not always made aware of matters in which a student may have been involved at a previous institution.” Generally, he said, if TSU discovers information about a prospective student, it “evaluates the risks associated with” his or her presence on campus.

“In all instances,” Freeman said, “the institution’s paramount interest rests with ensuring the safety of its students and campus community.”

Jackson’s academic transcript noted he was not in good disciplinary standing because of his expulsion, records show. A Google search also would have yielded alarming results.

Jackson wasn’t the first accused player Reed added to his team.

Quarterback-turned-wide receiver Treon Harris joined Tennessee State in 2017, a year after his suspension from the University of Florida football team amid a sexual assault investigation. It was the second time UF had suspended Harris for such an allegation; the first time was in 2014.

UF did not find him responsible in either case, records show. Harris struck a deal with the latest victim in which he apologized and voluntarily withdrew from the university in exchange for suspending the proceedings, according to a source with first-hand knowledge of the agreement who was not authorized to comment publicly on the matter.

The University of Florida is based in Gainesville and not affiliated with the University of South Florida, which is based in Tampa.

When coaches recruit players like Jackson and Harris, they send the message that sexual violence is tolerated, said Brenda Tracy, a national advocate who speaks out about her own 1998 rape by four men, including two Oregon State football players, and the impact it had on her life.

“I know what it looks like to have tens of thousands of people cheer for your rapist,” Tracy said. “All it does is normalize what the perpetrator has done and completely minimize the experience of victims.”

The players in Tracy’s case received a one-game suspension for what their coach called “a bad choice.” They were arrested but not prosecuted after Tracy declined to move forward with the case.

Since then, the mother of two has formed a nonprofit called Set the Expectation to curb sexual violence in sports. She has spoken before dozens of teams across the country.

Not among them is the Tennessee State football team, which in addition to Jackson and Harris recently featured yet another player shadowed by sexual assault allegations — quarterback Demry Croft.

Shortly after transferring from Minnesota, Croft was accused of rape by a TSU student and indicted in August on eight felony counts — six rape and two sexual battery, court records show. He has pleaded not guilty. He was suspended from the team as a result and no longer appears on the roster.

“Predators hunt where they’re safe and thrive in cultures that enable them,” Tracy said. “We’re teaching our young men that it’s OK to hurt people as long as they can throw a ball or run fast. It’s just a complete lack of regard for this issue and other humans.”

Second chances

At the other end of the spectrum is the University of South Florida, where until Dec. 1 head football coach Charlie Strong’s stance on violence against women was heralded as one of the toughest.

USF fired Strong earlier this month after a 4-8 record in his third season.

Strong suspended or dismissed at least four players arrested for sexual assault, including Jackson, during his decade-long head coaching career. While at University of Texas, he was one of the first Big 12 Conference coaches to publicly support restrictions on recruiting athletes responsible for sexual assault and domestic violence.

“If you are a student-athlete and you have a chance to go to University of Texas, go to Oklahoma, Texas A&M, Baylor, TCU, wherever you go, and then for some reason you did something that they had to dismiss you from that program, I don’t think that you should be given another opportunity to go to another major school and just start all over like your slate is clean,” he said at a 2015 press conference.

“I’m all into giving guys second chances, but I want to give guys on my team second chances, not someone else from another program.”

But Strong appears to have contradicted his own position by recently recruiting an athlete found responsible for sexual misconduct at a previous school. He then put that player in a special “sexual assault awareness” game on Sept. 28 that featured Tracy as an honorary team captain.

All the players wore purple-and-teal ribbons showing support for the cause.

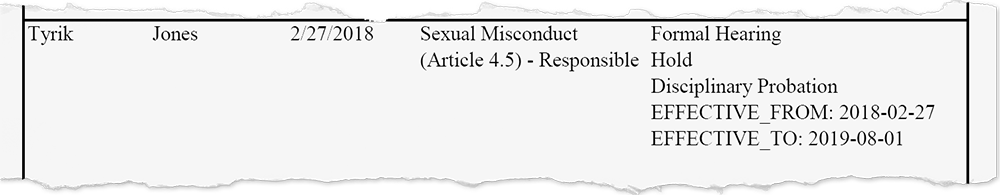

Except Tyrik Jones, a junior defensive end disciplined for sexual misconduct by the community college from which he transferred. No ribbon graced his helmet.

Jones declined to comment through a USF athletics spokesman. USF later said any missing decal was unintentional and may have been due to Jones’ use of a back-up helmet during that game.

According to a female student’s account in an Arizona Western College police report, Jones introduced himself to her after class one afternoon in October 2017. He invited her to his dorm room, which she declined, she said. But she agreed to give him a ride.

When they pulled up to the dorms, Jones began asking her questions such as, “Are you a virgin?” the report states. Then he reclined his seat and told her he had taken his penis out, she said. He told her to touch it, grabbed her hand and tried to pull it toward his groin, but she pulled her hand away, she said. He then reached over and fondled her breasts and groin area through her clothes as she tried to push his hands away, she said.

After suffering for months from stress and anxiety, the woman in February 2018 told campus administrators what happened, the report shows. She didn’t want Jones prosecuted, she said, but wanted the incident to be documented.

Following a formal hearing on Feb. 27, 2018, Arizona Western officials found Jones responsible for sexual misconduct and sanctioned him to disciplinary probation until August 2019. Jones was not on campus at the time, taking online classes remotely, officials said.

In December 2018, Strong signed Jones to USF’s 2019 recruiting class. He played six games this season, recording six tackles, a sack and a fumble recovery.

Strong declined to be interviewed but said in a Nov. 22 statement: “Neither I, my staff or our office of compliance was aware of any past issues involving Tyrik Jones when we signed him in 2018, and no information provided by Arizona Western or its coaching staff indicated an issue. Upon being made aware of a past issue, we followed standard processes in referring the information to the proper university office for a full review. That review is ongoing.”

Jones didn’t play for nearly two months after the sexual assault awareness game, but he returned to the field a day after Strong’s statement.

Tracers and loopholes

Most NCAA schools, including USF, have no policies for checking athletes’ backgrounds or formal procedures for responding when they become aware of a past incident, according to public records requests filed by the USA TODAY Network at more than 200 schools.

Many schools rely in part on questionnaire forms called “transfer tracers” to raise red flags. But tracers were never intended as substitutes for background checks, and they can give troubled athletes the false impression of a clean record.

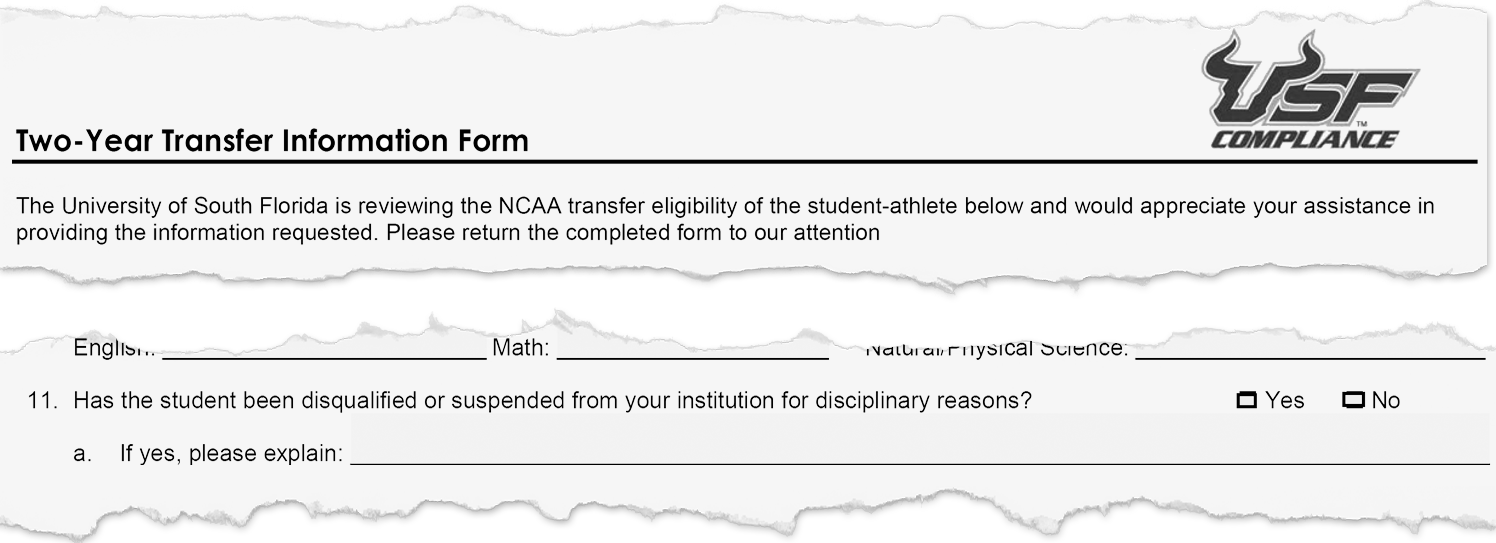

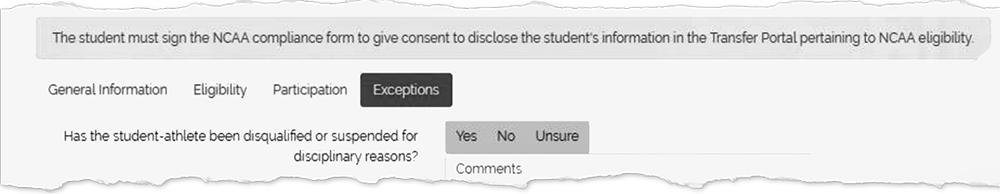

A transferring athlete’s outgoing school completes a tracer for the incoming school to determine NCAA eligibility. It includes questions about things like academic standing and whether the athlete was suspended or disqualified for disciplinary reasons.

But some tracers’ narrowly worded questions allow schools to withhold critical information.

The tracer USF sent Arizona Western regarding Jones asked, “Has the student been disqualified or suspended from your institution for disciplinary reasons?” “No,” Arizona Western marked, because he had been placed on probation — not suspended or disqualified, school officials confirmed.

Sometimes schools just answer incorrectly.

In March 2014, a female student told University of Kentucky police that football punter Tanner Blain sexually assaulted her at a party, an incident report shows. He was never charged criminally, but the university found Blain responsible for rape and suspended him for two years, a university attorney confirmed.

Blain did not return messages seeking comment, but his father told the USA TODAY Network that his son is innocent.

The university provided few details about the incident and redacted a campus police report almost entirely, saying it contains private information.

The report details the victim’s “efforts to fight (off) her attacker … her friends’ efforts to help her while the incident was ongoing,” and how the victim “escaped from her attacker and the private residence where the attack took place,” the university told the Kentucky Attorney General’s office in defense of its redactions against an appeal by the USA TODAY Network. The agency upheld the university’s redactions.

During his suspension, Blain transferred to El Camino College, a junior college in California. After a season there, he signed with San Diego State University, where he played two more years under head coach Rocky Long and helped the Aztecs win consecutive conference titles.

Time is a precious commodity for NCAA athletes, who have five calendar years to play four seasons in their sport. The “year of residence” rule is the one meaningful penalty the NCAA imposes on players suspended or expelled from school.

It benches them for a year when they transfer from the school that disciplined them directly to a new NCAA school, eating into their play time.

But athletes can avoid that penalty by stopping first at an intermediate school, like a junior college. By doing so, they technically transfer to the NCAA school from the intermediate school — not the school that disciplined them.

At the junior college, athletes can keep their skills sharp, competing at the lower level while completing at least a semester or associate degree. As long as they remain eligible and avoid trouble, they can transfer back to an NCAA school later and never lose that year.

Blain took advantage of the junior-college loophole and resumed play immediately after transferring to San Diego State.

“I take any allegation of wrongdoing regarding anyone affiliated with the San Diego State Football program seriously,” Coach Long said in a statement. “While recruiting individuals to join our University, we work diligently to obtain as much background information on the individual as possible.”

The San Diego State athletic department relies in part on tracers for checking athletes’ backgrounds, spokesman Mike May said. Although it sent tracers to both El Camino and Kentucky asking about prior suspensions, both forms came back clean, May said.

Kentucky’s failure to note Blain’s suspension on the tracer “was simply a mistake,” said UK spokesman Jay Blanton. The university’s student conduct office is required to notify its athletics department if an athlete is involved in a disciplinary proceeding, but that didn’t happen in Blain’s case, Blanton said.

Universities now use a standardized tracer on the NCAA transfer portal, a nationwide database of athletes seeking transfers. But its narrow question about disciplinary action carries the same limitations as the old forms. And schools still use their own tracers for transfers from junior colleges, which don’t have access to the portal.

Absent a more stringent NCAA policy, schools have no incentive to conduct proper background checks, said Kathy Redmond, founder of the National Coalition Against Violent Athletes.

Redmond sued the University of Nebraska in 1995, alleging it was liable for her rape by a football player because it ignored previous sexual assault complaints against him by other women. It was the first Title IX lawsuit of its kind, and the sides ultimately reached a settlement.

Tracers provide schools plausible deniability, Redmond said.

“They don’t want to know,” Redmond said. “They want to be able to say, ‘We had no idea.’ We hear that all the time. It’s just willful ignorance.”

Universities have a duty under federal and state laws to keep students safe, said Manly, the civil rights attorney who represented Nassar’s victims.

“That’s your primary job as a university administrator, and director,” Manly said. “If you have no policy to screen people that are coming in from other programs where they’ve been dismissed for safety, you’re violating the law, you’re violating the standard of care, and you’re placing your students in peril.”

Schools may have a legitimate legal defense if they did a proper check and no one told them about a previous student’s sexual assault, Manly said. But that defense weakens in the case of an athlete rebounding from a top program, he said.

“If you’ve got a star athlete who’s leaving a prestigious Division I college football program and going to some Division II or low-end Division I school, if you have a brain in your head, you’re going to be on notice that something’s wrong.”

Policy fails

In the absence of an NCAA policy against sexual violence, some of the organization’s conferences are taking the matter into their own hands.

Since 2015, six of the NCAA’s 33 Division I conferences — the Southeastern Conference (SEC), Big 12, Pac-12, Big Sky, Southern Conference, and Mid-American Conference (MAC) — have enacted policies or procedures to prevent the recruitment of violent athletes.

They generally require universities undertake due diligence to vet athletes’ pasts and prohibit those disciplined for sexual assault, domestic violence and other serious offenses from transferring in.

Yet some players still find their way in.

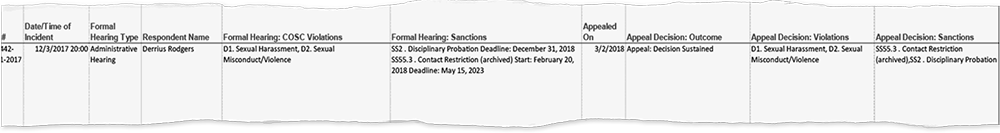

Two-time All-American sprinter Derrius Rodgers transferred to the Big 12’s Texas Tech from Illinois State University in 2018. He made his mark quickly, earning first-team all-conference honors in indoor track and helping the outdoor team win its first-ever national championship in June.

But months before his transfer, Illinois State administrators found Rodgers responsible for “sexual misconduct/violence” and sexual harassment stemming from a December 2017 incident, disciplinary records show.

The university placed him on disciplinary probation until the end of 2018 and imposed a contact restriction until May 2023, records show. The school upheld its decision after hearing his appeal.

Illinois State refused to provide additional details on Rodgers’ offense. Campus and local police said they have no incident reports.

Rodgers declined to comment.

Texas Tech said it didn’t know about Rodgers’ disciplinary action. His tracer form from Illinois State was clean — it only asked if he was disqualified or suspended — and the disciplinary action was not mentioned in communications with his former sprints coach, said athletics spokesman Robert Giovannetti.

Illinois State disputed this. “It is the University’s understanding that Texas Tech was informed that the student had troubles on campus,” athletics spokesman Mike Williams said.

Two weeks later, Texas Tech’s Giovannetti clarified: “While we were told that there were problems with girls on the team, we were also told they were handled internally.” He added, “There was no mention of a university Title IX issue.”

Giovannetti said coaches “conducted reasonable due diligence,” as is Big 12 policy. But that did not include obtaining Rodgers’ past disciplinary records — a step Texas Tech took after the USA TODAY Network brought the case to its attention, Giovanneti confirmed.

Rodgers’ offense would not have automatically disqualified him anyway. Big 12 policy allows schools to define “serious misconduct” on their own, as well as what it means to have “committed” it.

Some schools in the conference, including Oklahoma State University and the University of Kansas, define “committed” to include violations of the student conduct code. But Texas Tech and other Big 12 schools cover only criminal convictions in their definitions.

Rodgers remains on the track roster.

NCAA punts

The NCAA’s own study group, the Commission to Combat Campus Sexual Violence, last year advocated for the organization to tie athlete eligibility to behavior.

In its final recommendation, the commission “encouraged the board to direct the divisional governance bodies to consider legislation that reflects an Association-wide approach to individual accountability,” minutes from the board’s August 2018 meeting show.

But the NCAA Board of Governors did no such thing and disbanded the group instead. It promised, however, to “continue to monitor and track on sexual violence issues,” meeting minutes show.

Two major developments occurred behind the scenes in the months before the board punted on the opportunity.

Out West, members of the Big Sky Conference were unveiling the most comprehensive misconduct policy in college sports to date. It requires all their athletes to complete an annual questionnaire disclosing their involvement in any criminal, civil or juvenile investigations for serious misconduct. It also prescribes specific definitions for disqualifying offenses and includes a robust appeals process.

Big Sky’s then-chief Andrea Williams was also serving at the time on the sexual violence commission. She planned to present this sweeping new policy at the group’s final meeting.

Meanwhile, out East, Stony Brook University in New York was facing backlash amid revelations that, five years earlier, it recruited a football player while he was under investigation for sexual assault.

University of Idaho wide receiver Jahrie Level became the subject of an investigation at his school in May 2013 but withdrew and transferred to Stony Brook the following month. By the time Idaho found him responsible for sexual misconduct and expelled him in October, Level was already playing for Stony Brook.

And because Level transferred before getting disciplined — another loophole to avoid the year of residence — he faced no bench time at Stony Brook. Level competed for two seasons. He has been arrested at least three times since but not convicted, records show.

Level did not respond to multiple phone and social media messages seeking comment.

When the case made headlines last year, Stony Brook’s then-President Samuel Stanley was also serving on the NCAA Board of Governors. He was among the members who heard the commission’s final recommendation to direct the NCAA divisions to consider legislation like the Big Sky’s policy across all member schools.

And he was among the members who all but killed it. According to the minutes from that meeting, the board determined the commission had completed its charge to merely “explore” the issue. Over a year later, no action has been taken.

Mairin Jameson, a former University of Idaho diver, was the one who reported Level for sexual assault in April 2013. The incident was the culmination of weeks of inappropriate touching and verbal harassment, she said. At a bar one night, he walked up to her from behind, put his fingers up her skirt and rubbed her underwear from the front to the back, she said.

She remembered being “shell shocked” when she saw the news of Level’s transfer. Until that point, she didn’t know the NCAA allows athletes to transfer and play while under investigation.

“For him to just get to transfer and continue to do what he loves, really with no consequences, was upsetting to me first and foremost,” Jameson said. “My second feelings were of fear for the women on Stony Brook’s campus.”

During his senior year at Stony Brook, Level was jailed on charges of obstructing someone’s airway, an offense below strangulation, records obtained show. The charge was dropped, which in New York means the case is now sealed.

Stony Brook refused to provide documents, but an arrest record from Suffolk County shows the case was linked to Stony Brook University police.

Level has since been arrested at least twice in his home state of Florida on felony charges of grand theft and carrying a concealed firearm. The charges were dropped.

“I never felt like it was fair that Jahrie got to just go on with his life and play when mine was so affected and continued to be affected,” Jameson said. “I think playing sports is a privilege, and once you take that for granted and make mistakes that affect another person, you should lose that privilege.”

Stanley declined to comment for this story. He is now the president of Michigan State University, which continues to be scrutinized for its handling of Larry Nassar. More than 300 of his victims have come forward.

Stony Brook said in a statement: “We speak with coaches and administrators at the former institution(s) of all transfer student athletes. In accordance with our process, these conversations occurred prior to Jahrie Level transferring to Stony Brook and no disciplinary history was reported.”

Jameson said college athletes should be subject to a code of conduct, and sexual assault should be a disqualifying offense. She said she understands college sports is a business that makes money for universities but believes some coaches and administrators “get lost in that instead of doing what’s right.”

“I think the NCAA,” she said, “needs to take care of female athletes and other women on campus who are affected by this.”