Virginia Holleman poses with a photo of her son at her office in Oklahoma City. Chris Landsberger | The Oklahoman

looking for answers

Virginia Holleman went to bat for her son when he was denied coverage for mental health and substance abuse issues.

In crisis and out of answers, Virginia Holleman knew she couldn’t quit.

Her only son was in a spiral. An addiction to a dangerous combination of cocaine and anti-anxiety medication had him becoming more volatile by the day.

As Holleman, 53, pieced together the problems her 17-year-old was facing, she knew it was beyond her ability to fix.

His addiction left him a shell of the once fun-loving and gentle-natured kid she had raised.

“If he didn’t get help, he was going to die or end up in prison,” Holleman said. “He had done a 180 and was so out of control that we were scared for his life.”

Not knowing where to turn, Holleman looked for help from the experts. She found a youth treatment facility in Texas that specializes in drug abuse.

Holleman works as an insurance lawyer, specializing in claims for home, auto and life, so she knew enough to check her policy booklet for her Blue Cross and Blue Shield of Oklahoma health insurance.

She found one sentence: “Your Benefits for the treatment of Mental Illness include treatments for drug addiction, substance abuse and alcoholism.”

If he didn’t get help, he was going to die or end up in prison. He had done a 180 and was so out of control that we were scared for his life.”

“Perfect,” Holleman said she remembered thinking. “We were so relieved he was going to a safe place and to know that help was on the horizon.”

Believing her policy was clear, Holleman took her son to the facility, taking the first step in repairing her family and bringing her son back from the brink.

But two days after she dropped him off, Blue Cross and Blue Shield of Oklahoma called her and delivered a bomb.

Her son’s treatment was not going to be covered as they deemed it unnecessary.

“I could not believe it,” she said. “I had people talking to me in basically a foreign language to tell me why we were being denied.

“Here I am, an insurance coverage attorney, and I can’t figure this out. What is the deal?”

Mental Health Parity

Holleman’s fight for coverage is indicative of many families looking for answers from insurance providers when it comes to mental health coverage.

She was given multiple reasons for denial, but her insurer’s main reason was that treatment wasn’t medically necessary because her son wasn’t suicidal or homicidal.

In a survey of more than 1,200 individuals, more than 30 percent were denied, delayed or limited coverage for mental health and substance abuse services, according to the National Alliance of Mental Illness.

A new bill in Oklahoma is intended to help ensure federal requirements are met for health parity. This includes requiring insurance companies treat mental health disorders such as Schizophrenia, eating disorders or drug addiction with the same coverage options as those with a disease such as diabetes, cancer or AIDS.

The Mental Health Parity and Addiction Equity Act, which was passed in 2008, prohibits discriminatory insurance coverage for those with mental health and substance use disorders.

Even with federal law demanding parity, mental health groups around the country say insurers fall short of true parity and enforcement is inadequate.

The result has left millions of Americans at risk.

I think it’s very important that we do this to help those that truly are dealing with mental health. I think it’s one of those that could actually save lives.”

In Oklahoma, Senate Bill 1718, which addresses the parity issue in Oklahoma health coverage, already unanimously passed through committee and is expected to be heard soon by lawmakers who have shown the measure bipartisan support.

The bill would replace references in state law to “severe mental illness” like schizophrenia that must be covered with the broader “mental health conditions and substance abuse disorder.”

The bill would also prohibit insurers from imposing different limits on mental health care than they do on comparable medical care.

Sen. John Haste, one of the bill’s co-authors, said the bill will help families get the treatment they need and save lives.

“This is kind of where cancer was a lot of years ago when the coverage wasn’t happening,” Haste said. “Today, it’s just standard coverage. I think it’s very important that we do this to help those that truly are dealing with mental health. I think it’s one of those that could actually save lives.”

Around a half-dozen other states have bills similar to SB 1718.

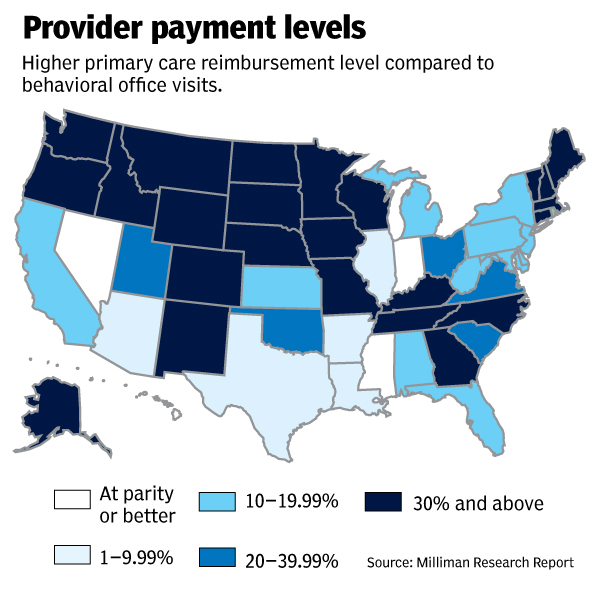

Prices to pay

For many families, the relief can’t come soon enough.

In 2017, 47,000 Americans died by suicide and 70,000 from drug overdoses, according to data from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. More than 17.3 million adults suffered at least one major depressive episode.

From 2008, when Congress passed the parity act, to 2016, the rate at which Americans died by suicide increased 16%. The rate of fatal overdoses jumped 66% in the same period.

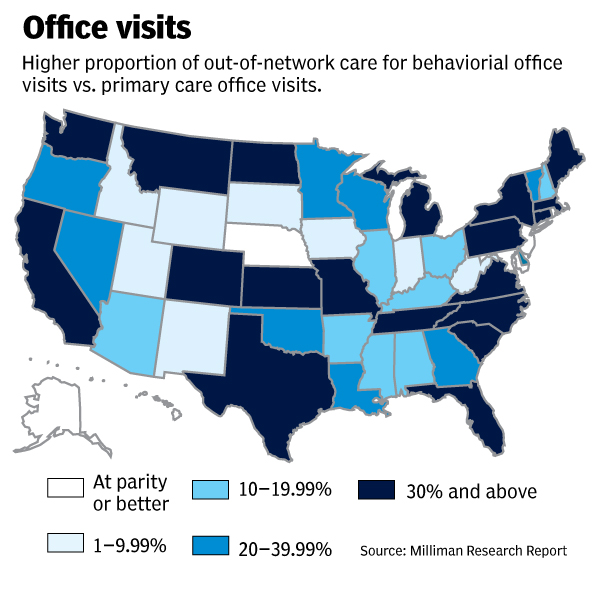

Despite federal law saying insurers must treat substance abuse and mental health conditions the same as any other sickness, advocates say there is a lack of enforcement that allows insurers to skate by.

Federal rules don’t say how to measure whether a health plan’s network of mental health providers is sufficient, so insurers have discretion over what they deem is an adequate network.

“The health insurers are not following the federal law requiring parity in the reimbursement for mental health and addiction,” President Trump’s commission on the opioid crisis wrote in its report in November 2017. “They must be held responsible.”

The Kennedy Forum, which works nationally to advocate for states to adopt legislative requirements like the ones currently being considered by Oklahoma’s Legislature, estimates mental illness costs the US nearly $200 billion each year. Yet only one in three patients who are diagnosed with a serious mental illness receive minimally adequate treatment.

Todd Pendleton | The Oklahoman

David Lloyd, a senior policy advisor for The Kennedy Forum, explained how behavioral health problems are financially costly for more than just those struggling with the health issues.

“They often lose their jobs and might go on unemployment, go on disability and not pay taxes,” Lloyd said. “When that happens, ultimately a lot of the costs fall on taxpayers.”

Lloyd said no single insurer is to blame, and that nearly all insurance providers struggle to provide true parity. But the financial and personal benefits should encourage attempts to improve.

“When people get the help they need you prevent pushing the cost downstream,” Lloyd said. “And of course, you save lives.”

For Holleman, the need to help her son outweighed any potential financial pitfalls.

She was told by the treatment facility she would need to come up with thousands of dollars out of pocket to keep her son in treatment.

She filed multiple appeals; and a complaint with the state insurance commissioner and in the end, Blue Cross and Blue Shield did end up paying for her son’s treatment.

The total cost for his 67 days in treatment came out to just over $26,000. Holleman had to pay approximately $11,000.

More transparency

When asked if the state’s largest insurance provider would support more transparency, like what is being suggested in Senate Bill 1718, to help ensure parity for mental health and substance abuse coverage, the company’s president released the following statement, but did not address the bill specifically.

“At Blue Cross and Blue Shield of Oklahoma, we believe in taking a holistic view to understand the emotional, physical and mental aspects of a person’s health that can lead to a better overall quality of life,” wrote Joseph Cunningham, M.D., Blue Cross and Blue Shield of Oklahoma president. “Our medical, pharmacy and behavioral health benefits all work together to ensure the best possible outcome. We have a dedicated internal department focused on timely review and compliance with the federal Mental Health and Addiction Equity Act that was passed in 2008.”

The company also pointed to a recent announcement in which the company award a $250,000 grant to Oklahoma State University Center for Health Sciences Addiction Medicine Specialty Clinic to address addiction and mental health in Oklahoma by improving access to behavioral health care.

A page on the insurance company’s website was designated to explain mental health parity and what the company is required to cover under the Mental Health Parity and Addiction Equity Act of 2008 and what limitations there are in coverage.

Near the end of the list of what’s covered is a disclaimer: “The Mental Health Parity and Addiction Equity Act of 2008 does not require plans to cover mental health or substance use disorders. However, the law generally applies if a plan covers both mental health or substance use conditions and medical or surgical conditions.”

Under limitations, Blue Cross and Blue Shield is less clear: “This information is coming soon,” followed by an urging to contact a customer service line.

‘Lives will be saved’

Since her fight with her insurer began in 2018, Holleman has not stopped researching and trying to help other families navigate the process of finding help for their loved ones.

She helped create an Oklahoma City Chapter of Parents Helping Parents, a peer-to-peer group where parents with children struggling with addiction share resources and guidance. She serves on the board of directors for Teen Recovery Solutions.

Holleman’s son was able to graduate from high school and is taking college classes now. She says recovery isn’t a straight path for anyone and says her family is grateful for each new day they are whole again.

Thinking on the importance of Senate Bill 1718, Holleman said she is immediately taken back to one of her first visits to see her son in treatment.

She and her husband Robert were checking into the visitor’s area when they saw him walk by with a group of boys his own age. He had a smile on his face and the light was back in his eyes.

She wants other families to have that same experience after battling the darkness of addiction.

“No family should have to go through what my family went through after our insurance company denied coverage and I am determined to help families in similar situations.” she said. “We were lucky because there have been numerous occasions when people have been turned away and have died as a result.

“I still have my son. If this passes, lives will be saved.”

If you or a loved one has experienced lack of coverage for behavioral health care and would like to tell us about it, email Adam Kemp at akemp@oklahoman.com