NOWHERE TO Go

New Hampshire has been ravaged by the opioid epidemic. Rockingham County, the second largest in the state, has no housing for people in recovery, especially the formerly incarcerated. This story is the first in a series.

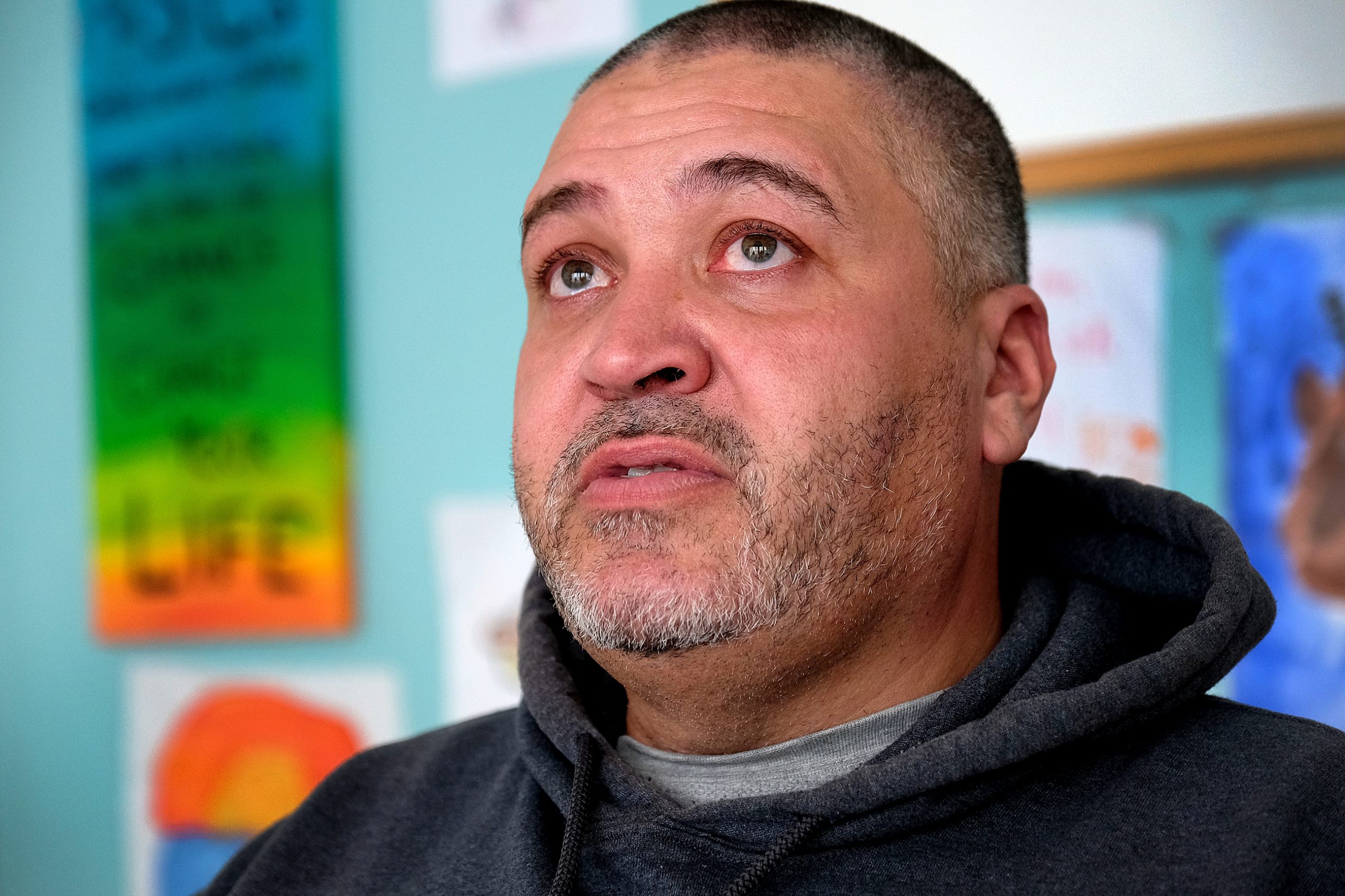

PORTSMOUTH — A thunderous man now living a rather gentle existence, Eric Mansfield stood inside his small, dorm-style room at the homeless shelter ahead of Thanksgiving.

On his twin bed, dressed by a royal blue blanket, lay a large sketchbook. His drug court certificates earned thus far were framed on the wall.

Frosty November air spilled in through his open window.

Mansfield pulled down the stretched-out neckline of his shirt to reveal a Mother Mary tattooed on his chest, one he did himself in prison.

“Except she’s holding a grenade,” he said.

That artwork was a distinct metaphor for Mansfield’s life up until last year — a suicide mission.

He grew up in Boston, and was addicted to heroin by age 13, after he and friends discovered the narcotic lying out on his parents’ kitchen table. They’d thought it was cocaine. His mother worked as a prostitute, and his father was her pimp.

“Shot, stabbed, caught on fire, broke almost every bone in my body” — Mansfield’s entire existence revolved around heroin, cocaine and meth. He was a member of the criminal street gang Gangster Disciples; regularly assaulting police officers and once was arrested in Hampton Beach driving a stolen car, high on heroin, with 1,000 rounds of ammunition in the back.

His criminal record contains hundreds of cases between Massachusetts and New Hampshire, equating to 27 years in prison — his entire adult life. Mansfield, who recently turned 49, chews at the inside of his mouth as he talks about it, tapping his foot on the linoleum floor in rapid succession.

But last January, after release from the Rockingham County jail in Brentwood, there was a bed opening at Cross Roads House — Portsmouth’s homeless shelter — where Mansfield would be able to stay while participating in the county’s drug court program, a post-plea option providing structured treatment and accountability for high-risk individuals who have faced a series of criminal charges. He later moved into the shelter’s transitional program, a separate lodging space.

Eric Mansfield, now 49, has spent half of his life in prison. For the first time since he was 13, Mansfield is sober and free of heroin, crack, crystal meth. Mansfield has been living at Cross Roads House in Portsmouth, and facing all of his previous infractions in drug court. Rich Beauchesne | Seacoastonline.com

For Mansfield, a safe place to lay his head at night was the start of a new, substance-free life. An off-ramp from the justice system, a softer passage into a hopeful recovery. But the foreboding reality is most are never given that chance.

Many are asking, does a community have a responsibility to provide a foundation for these individuals?

In a small state disproportionately ravaged by the opioid epidemic, its second most populated county — Rockingham — is destitute of transitional, sober and supportive housing options.

Aside from Cross Roads House — Portsmouth’s 96-bed homeless shelter — and the 63-bed Granite House for Men in Derry, there are no other options in the county. Meanwhile, in 2019, the Rockingham County jail processed 5,300 individuals.

Thirty-seven cities and towns blanketing New Hampshire’s southeastern corridor, Rockingham County has a rapidly growing population of more than 300,000 people. What it doesn’t have is any residential recovery infrastructure. Housing solutions remain elusive for almost everyone in recovery, especially formerly incarcerated citizens.

Jessica Norton, director of inmate services at the Rockingham County Department of Corrections, said upon release, she has seen men check into emergency rooms and lie that they’re suicidal, just so they are given a place to sleep. One former inmate, she said, sleeps overnight at Planet Fitness because the gym is open 24/7.

Others would prefer to remain in jail, where at least they have regular meals and a bed. There, they don’t have the often insurmountable responsibility to make ends meet.

Mansfield’s story is an anomaly, because he found housing and treatment. Many like him end up dead or committing crimes through to their death, unable to find a springboard to reintegration.

A 2012 report by the What

Works Collaborative and Urban Institute tagged housing for formerly

incarcerated individuals as the “literal and figurative foundation for

successful reentry and reintegration.”

“What

we are starting to see is when people with substance use disorders have a

supportive community that is meeting various needs, including stable and

affordable housing, they are much more likely to receive the treatment they

need and then continue in their recovery,” said Katherine Easterly Martey,

executive director of the New Hampshire Community Development Finance

Authority. “That community-level connection and having it start with

affordable housing is the basis for people’s success.”

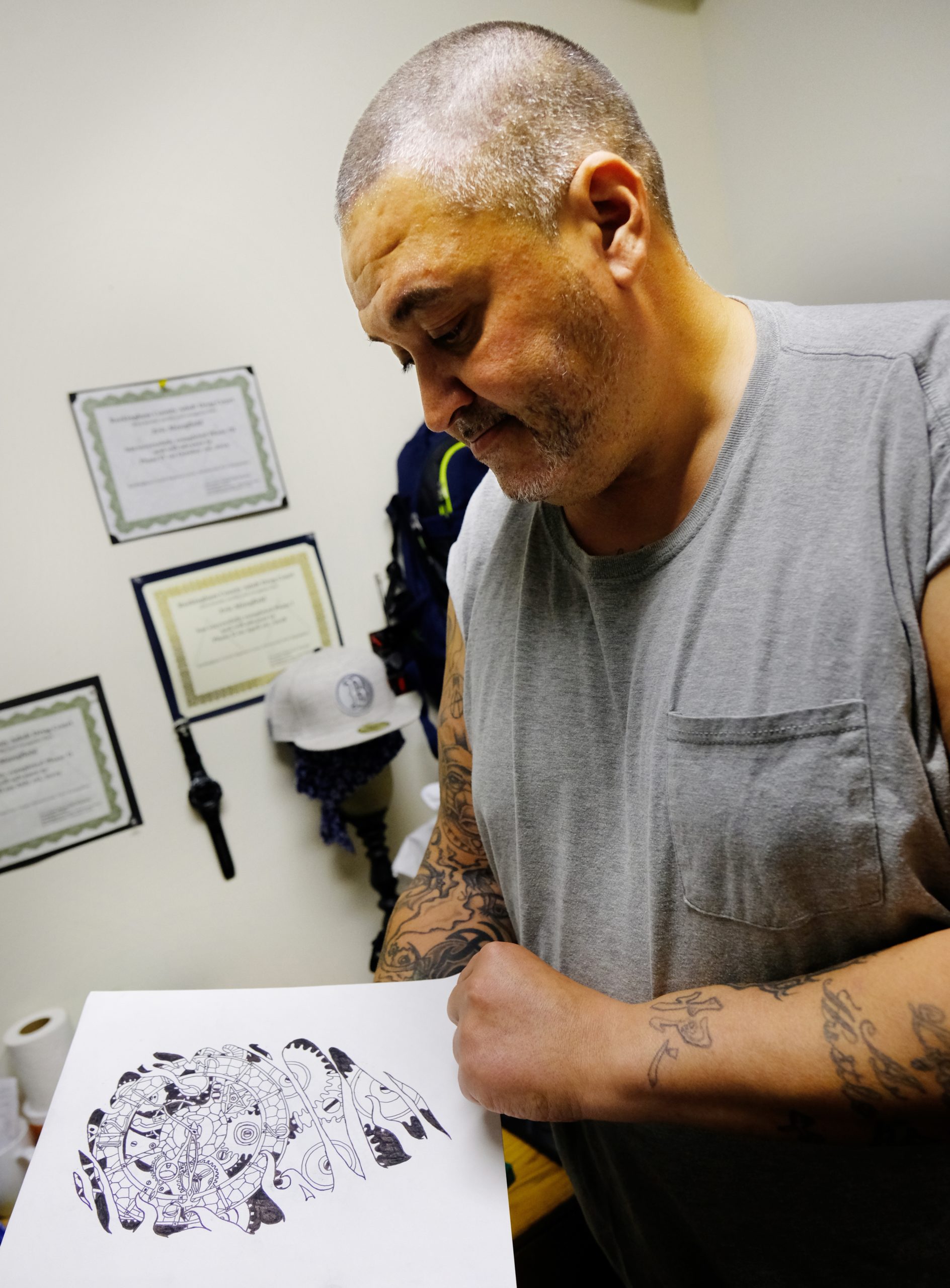

An angel sketched by Eric Mansfield. Hadley Barndollar | Seacoastonline.com

Fatal issue

Officials say whether or not Rockingham County bolsters its barren landscape of supportive housing for formerly incarcerated individuals battling drug addiction is a matter of life or death for many.

In 2017, the county tied for the second highest suspected drug use resulting in overdose deaths per capita — at 1.36 per 10,000 population — while the statewide total was an unprecedented 490 deaths.

Nationwide, approximately 9 million people are released from county jails each year, and formerly incarcerated people are almost 10 times more likely to be homeless than the general public, according to the Prison Policy Initiative. The latter statistic naturally increases their chances of recidivism.

More than two-thirds of jail detainees and half of prison inmates have substance use disorders nationally, according to the U.S. Department of Justice.

In 2019, at the Rockingham County jail, staff conducted medical intakes on 2,275 individuals, and 1,080 were placed on detox watch, according to data from the county corrections department. At the state’s prisons, based on a search of active medical diagnoses, the state estimates that more than 50% of incarcerated individuals have a diagnosis of opioid use disorder.

The correlation between drug-related deaths and incarceration history is currently a missing data set in New Hampshire, despite the state ranking among the top five in the country with the highest rates of opioid-involved deaths. The state departments of justice and corrections and the county jail do not maintain that information, they all said, and the Office of Chief Medical Examiner is currently working through confidentiality issues to do so.

Meanwhile, in Connecticut, officials publicize a startling data set depicting overdose deaths with a Department of Corrections record. That data was recently able to show former inmates account for more than half of the people who died from drug overdoses in Connecticut between 2016 and 2018, and the numbers continue to creep up, the Connecticut Mirror reported.

At this time, the fatal impact of drugs on New Hampshire’s justice system-involved population is unquantifiable, and rather anecdotal. But corrections officials certainly see drug deaths, housing and transportation as intimately intertwined.

“Any type of stumbling block, that’s it. We lose that person, figuratively and literally,” said Stephen Church, superintendent of the Rockingham County DOC. He said the first 24 hours after an inmate is released are the most lethal, largely dependent on what immediate structure the individual is able to find.

The cities of Manchester, Nashua and Concord have been able to design that infrastructure, but are deluged by people from across the state seeking their services. They’re natural locations for sober and transitional housing, as individuals can walk or take public transportation to work, appointments and necessities like grocery stores. City zoning is also more conducive to such housing models.

In Rockingham County, that’s not the case. Much of it is rural. And in its populated Seacoast, the cost of living is among the highest in the state.

There are plans in infancy for Rockingham County to construct a $44 million facility that would house a community corrections program — a 90- to 120-day drug treatment center with roughly 80 beds — among other offices, on county property in Brentwood. If the new facility is included in the fiscal year 2021 budget, the county delegation of state representatives will vote on it in the coming months, and if approved, a public hearing on the bond would be held next year.

Mansfield knows firsthand how onerous it is for an ex-offender to find treatment and housing. He spent nearly 30 years in a cell block between Massachusetts and New Hampshire. The difference, this time, in addition to truly wanting sobriety, was a bed and case management, he says.

“I would have died,” Mansfield said. “I know in my heart that I would have died.”

How to address the void of housing options for at-risk populations as such has left many in a daze, as there’s no easy money to be made from transitional and sober housing models, and state funding in tax-free New Hampshire is limited. It’s either up to the county and its taxpayers, or grants and federal dollars must be sought out.

The $64 million in federal opioid funds given to the Granite State over the last few years to address the crisis went toward creating “The Doorway” hub-and-spoke model, but Rockingham County didn’t get its own hub. And the funds haven’t been used to create any residential options, either, though state officials say that’s coming.

‘People ain’t gonna make it’

Years ago, when Mansfield was brought to a hospital room in chains to bid his dying father farewell, the nearby police officers and security guards called him “the devil’s son.”

His whole life had been permeated by pain and misery, he said, though he now realizes how much was self-inflicted.

“They say you hit rock bottom or you get to the bottom of the barrel, I was under the barrel,” Mansfield said.

Eric Mansfield, is a self-taught artist who keeps his sketches in a book for possible tattoo patterns. Eric has been struggling with substance abuse his whole life, but today is sober and living at Cross Roads House in Portsmouth. Rich Beauchesne | Seacoastonline.com

Mansfield estimates he’s witnessed more than 100 people overdose and die in his presence.

He, too, almost met death, and the woman he was with took pictures as it happened — his head laying in her lap. He keeps the picture on his cellphone as a reminder of that day, when he was later revived by Narcan.

Mansfield was 17 when an assault charge triggered his life in the prison system — at a juncture when Massachusetts still considered 17-year-olds as adults in its criminal justice system.

Since then, it’s been from the streets to jail, and back again — over and over.

After a 2011 arrest in Newburyport, Massachusetts, on larceny charges, a law enforcement official was quoted by the local newspaper saying “this is his job,” in regards to Mansfield’s criminal history. He was known well by most judges in the state.

“Stealing for drugs, always the same,” Mansfield said. “Everything that has happened to me is because of drugs. My whole life has just been chasing them, pretty much suffering the whole time.”

Mansfield was married before and has two children, both of whom he’s recently reconnected with after years of estrangement. He’s now been sober for nearly 14 months, since his last exit from jail on Jan. 23, 2019.

Last year, Mansfield was eligible for the county’s drug court program, but participants have to have an address to qualify — and one in Rockingham County, at that. Within one week of release, after a short stint at a transitional shelter in Strafford County, he was admitted to Cross Roads House in Portsmouth.

After his stay in the emergency shelter area, Mansfield was accepted into Cross Roads’ Transitional Shelter Program, where residents live in more private quarters and receive intensive case management support aimed at a return to permanent housing. In this program, acceptance depends on a commitment to living drug- and alcohol-free. The program has a capacity of 18 — six women and 12 men — but can only be accessed after a stay in the emergency shelter. The emergency shelter, at some points during the year, has an ongoing wait list of more than 150 people.

Eric Mansfield arrives back at Cross Roads in Portmsouth where he says that the place to come home to every night has given him a second chance at a sober life. Rich Beauchesne | Seacoastonline.com

Eric Mansfield often stops at the front desk at Cross Roads House to talk with members of the staff. Today, Jessica Parker, development director jokes around with Masfield who stopped using drugs in January 2019.

Cross Roads has been an empowering environment, Mansfield said, because everywhere he turns, there are caseworkers — he’s not alone with his own thoughts.

According to the nonprofit Corporation for Supportive Housing, approximately 75% to 85% of those who enter supportive housing are still housed after one year, and about one-third of those leaving move on to more independent living arrangements in the community.

Mansfield has been able to develop an armored fortitude and strength of mind — nothing will break his sobriety, he says. The giant man who once acted as a machete destroying his own life and the lives of others, now has a sense of tenderness.

“I never helped no one and now I want to help everybody,” Mansfield said, his voice cracking. “I don’t mind. I don’t mind being nice.”

He’s a skilled artist. Of the many drawings in his sketchbook, one depicts an angel carrying a flower-covered cross. Large roses at her feet are colored yellow and magenta. Beside her sits a dove.

While Cross Roads House gives Mansfield wraparound case management and a safe, consistent place to sleep, he notes the shelter itself is not a sober living environment. Many residents are still using, so temptation is everywhere. But the county’s only shelter shelter is having to fill the void for all other types of housing lacking in the region; transitional and recovery included.

“I got lucky, that’s all it is,” Mansfield said. “It took me 48 years. That’s a long time to finally get lucky, and that’s the problem. Addicts have nowhere to go, and the only place they have to go is back to the streets to get high or back to jail.”

He’s trying to get his driver’s license back, complete drug court, and forge a path toward permanent housing; another obstacle, since convicted felons are not allowed in most public housing, and the competitive market allows landlords to pass over potential tenants with a criminal history. He wants to make the despair mean something, by talking to justice system-involved youth before they head deeper in darkness.

“If you don’t have (shelter), your life will never, ever get back to normal,” Mansfield said. “Without some kind of help, stepping stone, somebody there to help you, you are never going to make it. This here, or a place like this, will save your life.”

He paused, looking out the window at a snow-covered parking lot during a later interview in December.

“The state and county gotta figure it out, because if they don’t, people ain’t gonna make it. It’s your decision to get sober, but having nowhere to go and still having your decision, pretty soon, you’re gonna get sick of that s***.”

Potential solutions

According to the U.S. Interagency Council on Homelessness, studies show communities spend less on shelters, jails, ambulances and emergency rooms when they invest in supportive housing models. And other New Hampshire communities have been able to do so — by establishing affordable housing with built-in services for vulnerable populations.

In February, U.S. Sen. Jeanne Shaheen, D-N.H., announced a $1.15 million grant for recovery housing in the state, to be administered by the New Hampshire Community Development Finance Authority, as a means to fill a gap in the funding of supportive housing projects across the state. Shaheen noted the stability that comes with “affordable, supportive housing” for society’s most vulnerable.

It’s too early to say if projects in Rockingham County will get a share of that money.

The NHCDFA recently granted $500,000 to Sullivan County, for example, to acquire and re-purpose a commercial building in downtown Claremont to house the “TRAILS” program — transitional housing and supportive services for ex-offenders trying to get back on their feet, into the workforce and their communities. The building will include 28 recovery beds for men and 14 for women, with room for expansion.

TRAILS, which started in 2010, has seen success in the form of a recidivism rate just below 20%, half of the state’s reported rate.

Strafford County provides county-funded transitional housing for men and women who are transitioning from the Strafford County House of Corrections. The program was kick-started in 2009 by a $190,000 federal grant from the Department of Justice. In 2016, it housed 127 male residents and 55 female residents in transitional living, with an average length of stay of 41 days.

Mansfield compared New Hampshire’s resources to those of his home state of Massachusetts, which has a “sober home industry.” The business model has its fair share of critics, because many homes typically go unregulated, resulting in facility mismanagement and sometimes overdoses. But done properly, sober homes can offer support, camaraderie and a safe environment.

In Manchester, where the city’s fire chief estimates the existence of 50 to 60 such homes, officials are calling on the state to establish a mandatory registration and inspection of sober homes, which otherwise can operate inconspicuously in residential areas and are often subject to neighborhood opposition.

A nonprofit called the Massachusetts Alliance for Sober Housing oversees operation and standards of 170 “MASH” certified homes, for example. A similar effort recently came online in New Hampshire, affiliated with the National Alliance for Recovery Residences, called the New Hampshire Coalition of Recovery Residences. Only eight organizations are NHCRR-certified so far, as registration is voluntary at this time.

Annette Escalante, director of the state’s Bureau of Drug and Alcohol Services, acknowledged the infrastructure void in Rockingham County, but noted counties around the state are having the same conversation.

On March 6, the Governor’s Commission on Alcohol and Other Drugs approved $1 million in new funding to expand transitional housing in New Hampshire, and $350,000 to go towards recovery housing, particularly in under-served areas.

Commission Chairman Patrick Tufts, CEO of the Granite United Way, said the Bureau of Drug and Alcohol Services will ultimately put out a request for proposals for those interested in getting a piece of the funding. The commission has been taking its queues from people in the field, he said, where transitional and recovery housing has been identified as a “critical gap.”

“We’re trying very, very hard,” Escalante said. “Hopefully we can make some sort of dent.”

About this project

Seacoast Media Group is exploring the absence of transitional, sober and supportive housing options in New Hampshire’s Rockingham County, as an opioid crisis trudges onward. While New Hampshire ranks in the top five states with the highest overdose death rates per capita, residential and shelter options remain elusive for many, especially formerly incarcerated citizens. In the state’s jails and prisons, approximately 50% to 65% of incarcerated individuals have substance use disorders.

This series will continue throughout 2020. If you have questions or suggestions, email reporter Hadley Barndollar at hbarndollar@seacoastonline.com.