LIVING IN LINDEN

Exploring a neighborhood's struggles and possibilities

City says efforts to revive long-troubled Linden working; residents skeptical

In one of Columbus’ most challenged neighborhoods, homes are sprouting where abandoned houses once stood. More babies are surviving long enough to dig into their first birthday cake. Fewer people are being robbed at gunpoint.

The data suggest that City Hall’s efforts in Linden are working, but residents and neighborhood leaders say it doesn’t necessarily feel much different yet.

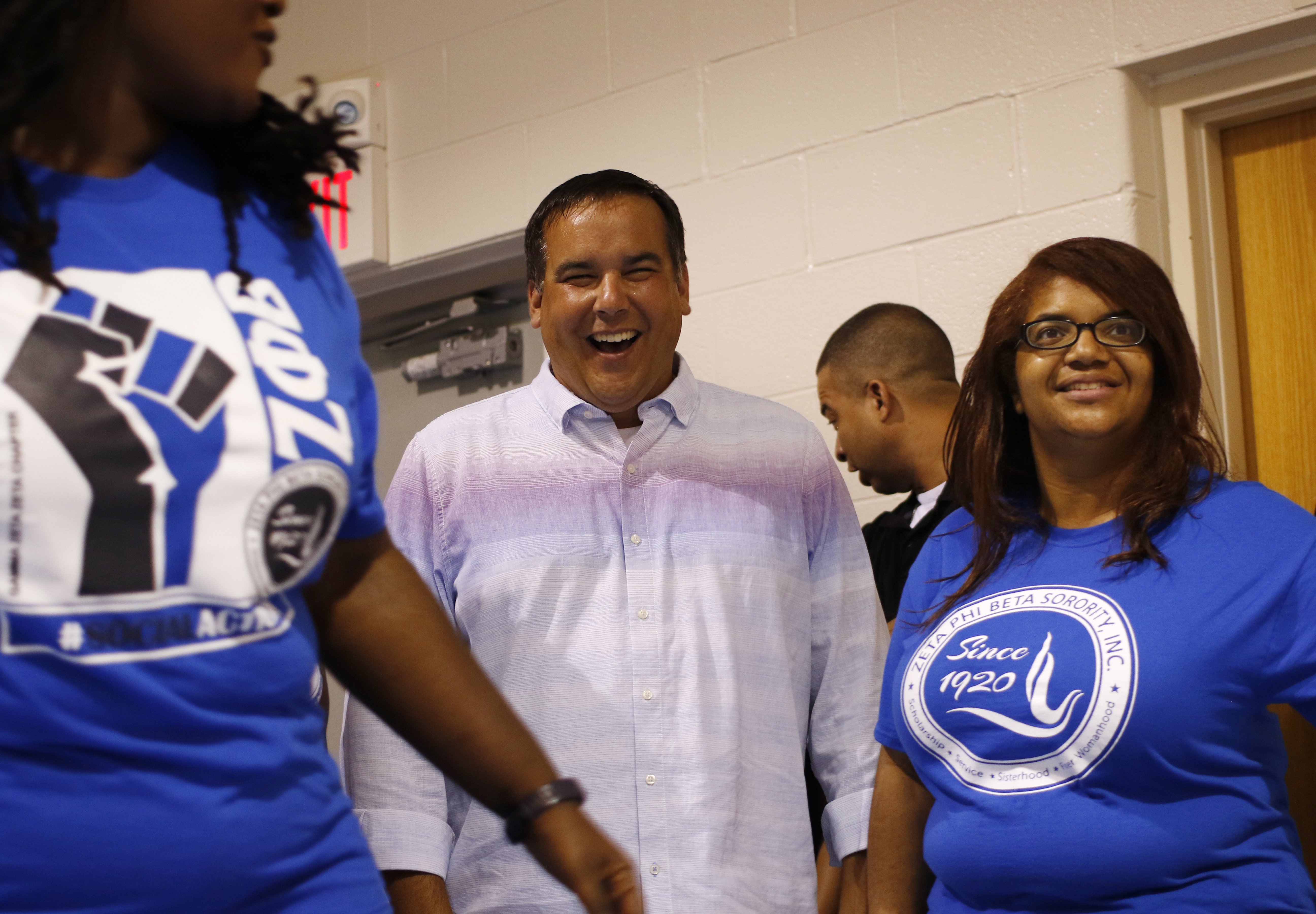

Since Mayor Andrew J. Ginther was elected in 2015, he has said his top priority is neighborhoods. Nowhere has the spotlight been brighter than in Linden. But progress takes time, said city officials and neighborhood leaders. They say that Linden’s problems have marinated for decades, and they will take years to fix.

“That’s a hard pill to swallow when you’re living in it now,” said Carla Williams-Scott, director of the city's Department of Neighborhoods.

On Cleveland Avenue, vacant storefronts still stare back. If you need fresh produce in Linden, you have to drive to another neighborhood. Crime might be reduced, but the neighborhood’s reputation hasn’t changed.

Columbus is demolishing more abandoned properties, and parts of Ginther’s wide-ranging safety plan to cut down on crime focused on Linden. Other efforts have sought to tackle infant mortality, transportation issues and poor access to fresh produce.

After 18 months of research, the city is on the verge of rolling out its Linden community plan — a long-term proposal to revitalize the neighborhood.

The plan will be the centerpiece of the city’s work in the neighborhood, but city officials acknowledged that some neighborhood residents are skeptical because past plans weren’t executed.

“I think it’s absolutely a fair assessment for anyone to ask what’s going to be different about this one,” said Adam Troy, director of the Community of Caring Development Foundation, a development arm of New Salem Baptist Church.

Ginther said his administration had to show an “immediate commitment and investment” in the neighborhood first. The city located the newly formed Department of Neighborhoods at the Clarence J. Lumpkin Point of Pride Center in the heart of the neighborhood.

The city lined up Huntington Bancshares to remodel a vacant Meijer store on Cleveland Avenue in Northland into office space and lend $300 million in low- to moderate-income neighborhoods such as Linden. When the city gave the developers of Easton a $68 million tax break, the city netted about $5.75 million for Linden.

The city’s own capital budget, though, has ebbed in its support for Linden. North and South Linden combined represented 2.7 percent of capital spending through August 2018, down from 4.8 percent in all of 2017. Since 2014, the city has spent about $100 million of its $2.3 billion in capital funding in Linden.

Linden also benefits from citywide projects, the largest category of spending, Robin Davis, Ginther’s spokeswoman, said in an email. Other neighborhoods where spending eclipses Linden have water- and sewer-treatment plants with projects that inflate spending.

The neighborhood also is in line for several large projects: a $25 million reconstruction and expansion of the Linden Community Center and Linden Park, a new fire station and rain gardens to help with storm-water runoff.

More city spending will follow in Linden as the city rolls out the new community plan, said Council President Shannon G. Hardin.

“As we go into the implementation phase, it’s only logical there will be physical investment needed,” he said.

Ginther’s administration says it is making progress in the neighborhood. The number of babies who died before their first birthday decreased from 45 between 2008 and 2012 to 39 from 2013 to 2017, even though the number of births increased.

Smart Columbus plans to launch multi-modal trip planning, a transit card that can be used across transportation modes and kiosks where residents can access trip planning tools next year in Linden. It also is working on a way to provide on-demand transportation for pregnant women to get to the doctor.

After Kroger left the Northern Lights shopping center, the city spent about $40,000 to help start a farmers market in the neighborhood on summer Sundays to help bring fresh produce to the neighborhood. The market expects to return in 2019.

In 2017, Linden had 884 vacant properties, down from 1,388 in 2013. Much of that is attributed to the 367 demolitions during that period, but about one-third of structures the city's Land Bank acquires in Linden are sold for rehabbing, according to the city's Department of Development.

On some of those vacant lots, Habitat for Humanity is building new houses. Residents are mixed on whether that’s a good thing, though.

Nate Wilkins, a longtime neighborhood activist, regularly chides city officials about abandoned properties, but he wants to see more of them rehabilitated instead of razed, to maintain the historic character of the neighborhood.

“As the city tears down homes, people aren’t going to be able to afford to live here,” Wilkins said.

More private investors are needed to rebuild the Cleveland Avenue corridor, the commercial spine of Linden, said Kwodwo Ababio, owner of New Harvest Cafe. Ababio is optimistic about the city’s plan for Linden, but after 14 years in business, he is looking for others to follow him to Linden.

The city is working with the Mid-Ohio Regional Planning Commission on a corridor study that includes Cleveland Avenue. Improving the corridor is a priority for the city, but to attract residents and businesses, it has to change the perception that Linden is dangerous, Hardin said.

“When people feel safe, they feel secure. When they feel secure, they want to invest,” said Troy, of the Community of Caring Development Foundation.

As police investigated a record number of homicides in 2017, Ginther launched a new safety strategy and vowed to hire 100 more police officers. Part of the safety plan was to put more bicycle patrols in Linden so that officers would interact more with residents.

Violent crime ticked up in Linden during the period when bicycle officers were on patrol in the neighborhood over the summer, but gun-related violent crime reports dropped. After a spike in homicides during that period in 2017, they dropped back to 2016 levels this year, according to a report about the program.

The city also launched a violent-crime review group in which city departments marshal forces to respond to the neighborhood in 48 hours with social workers, investigate 311 complaints about problems that could attract crime, and determine whether gang connections existed.

The group has responded to six cases in Linden. It is learning more about the crimes, including that all of the victims knew their suspected attacker. That indicates that a person walking the streets of Linden probably isn’t the typical target of random, violent crime, said Dr. Mysheika Roberts, city health commissioner.

“In order for people to want to come to Linden and settle down," said John Lathram, a member of the North Linden Area Commission, "you have to get rid of the crime, get rid of the prostitution. You have to clean it up and get rid of the trash."

Like what you're reading?

Stories that inspire. Coverage that informs. Investigations that affect change. This is real news just when it's needed most. Subscribe today Subscribe