Kent State shootings: Iconic image stokes anti-war sentiment across US

By Bob Dyer, Akron Beacon Journal

May 3, 2020

The first display you see upon entering Gallery I at the May 4 Visitors Center at Kent State University expresses a concept initially advanced by famed playwright Arthur Miller.

“May 4, 1970, was the day the war came home.”

And nothing brought the Vietnam War home more dramatically than a photograph taken that day by a Kent State photojournalism major.

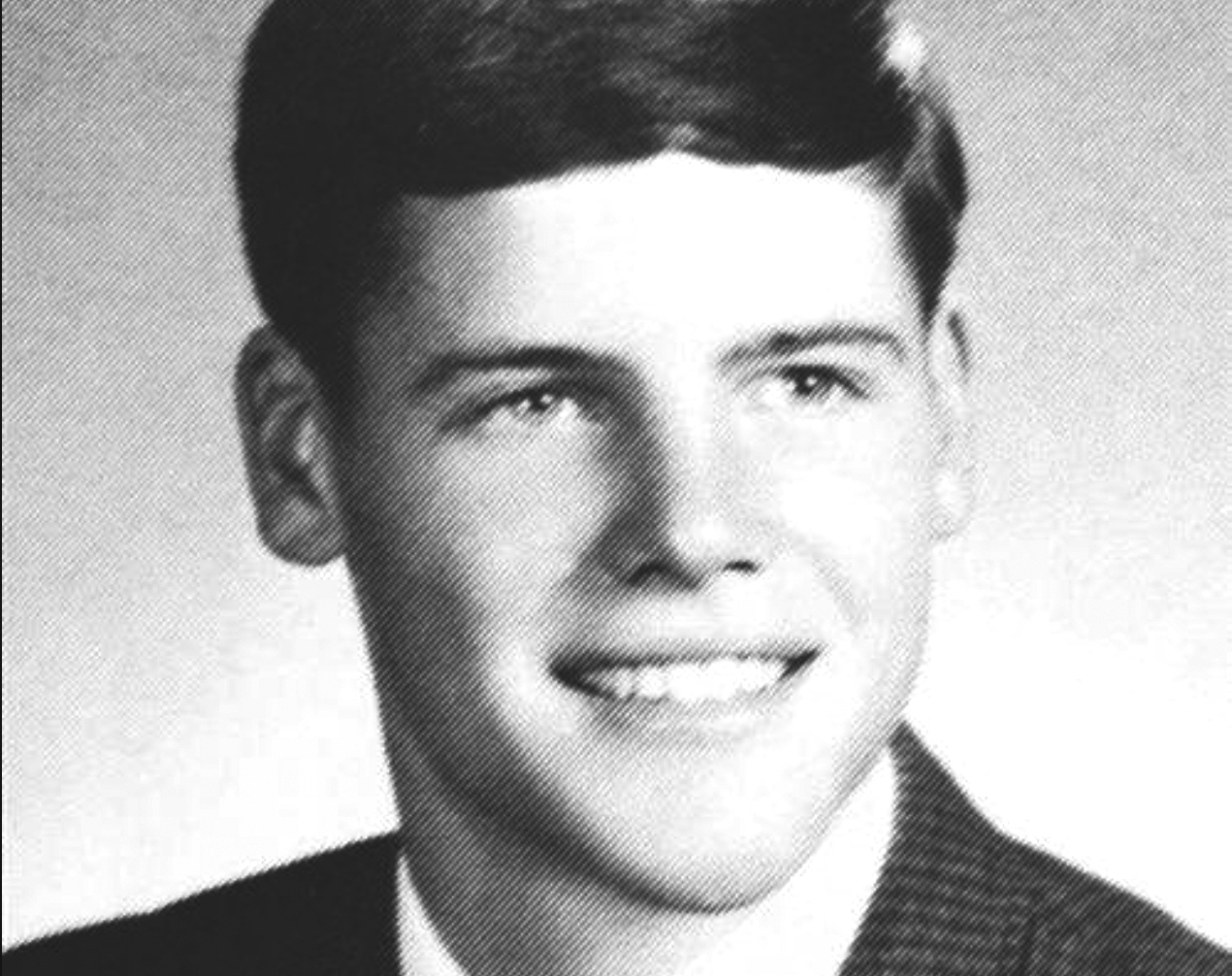

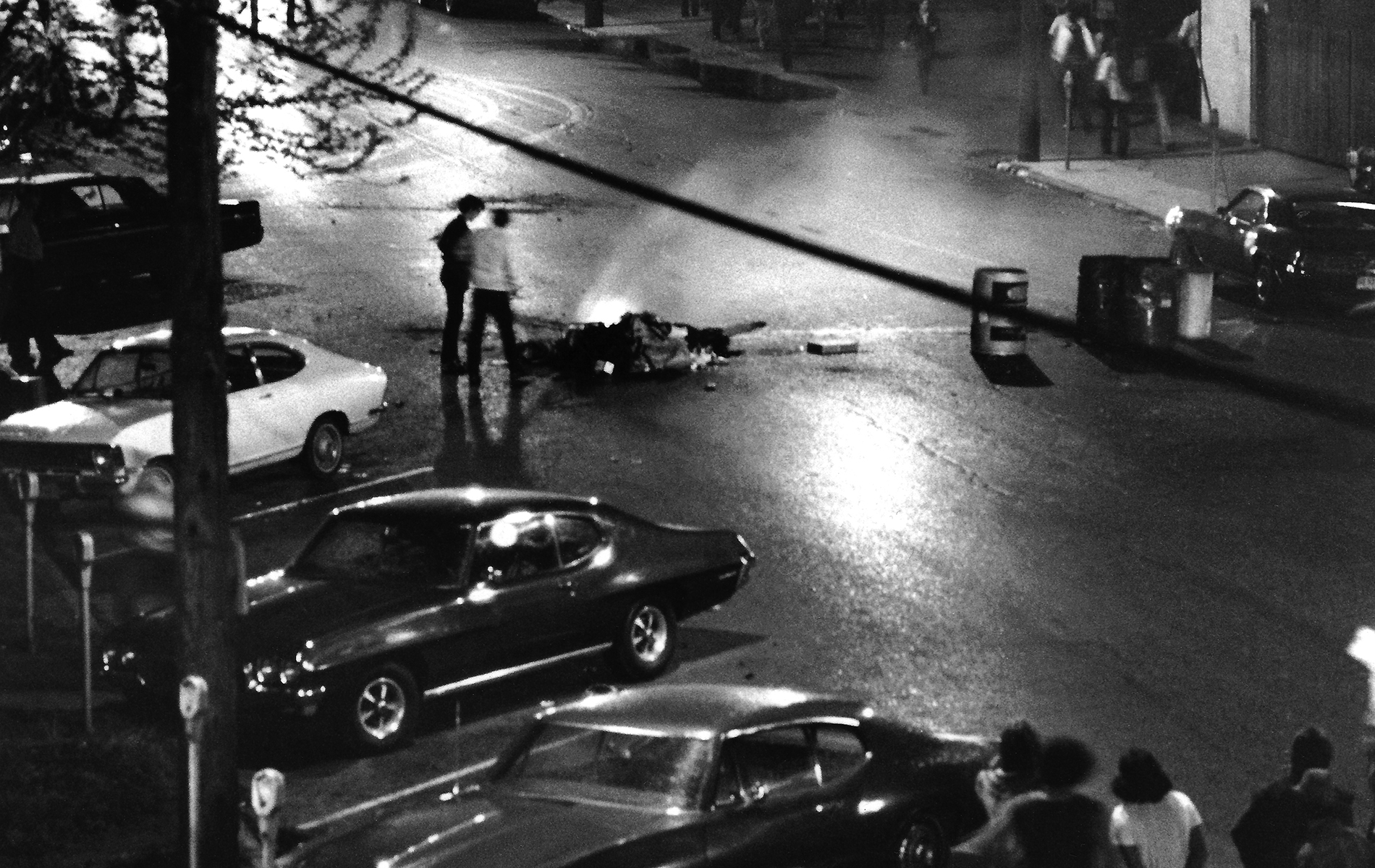

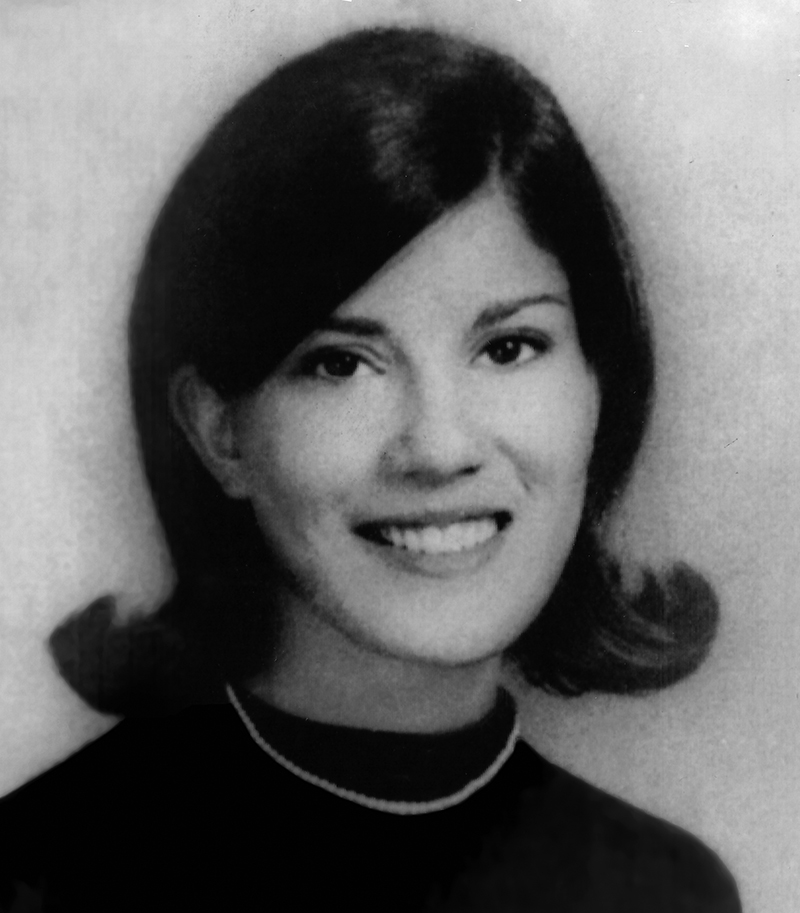

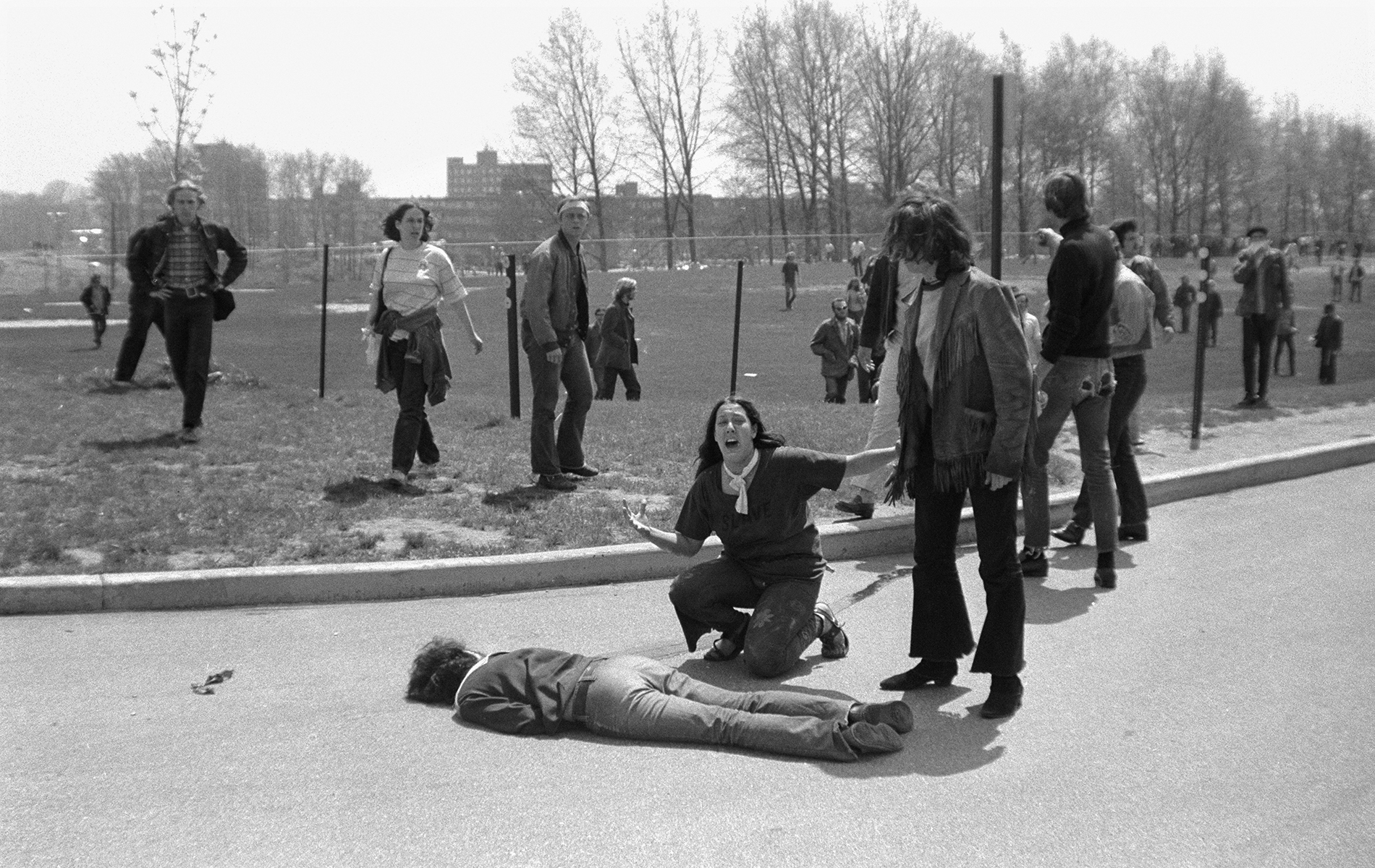

You probably already know which photo we’re talking about: Young Mary Ann Vecchio kneeling next to the dead body of student Jeffrey Miller, her hands turned upward in despair, a look of horror on her face.

It was the face that launched a thousand protests.

It was the face that mirrored the nation’s shock that American soldiers would fire into a crowd of unarmed students.

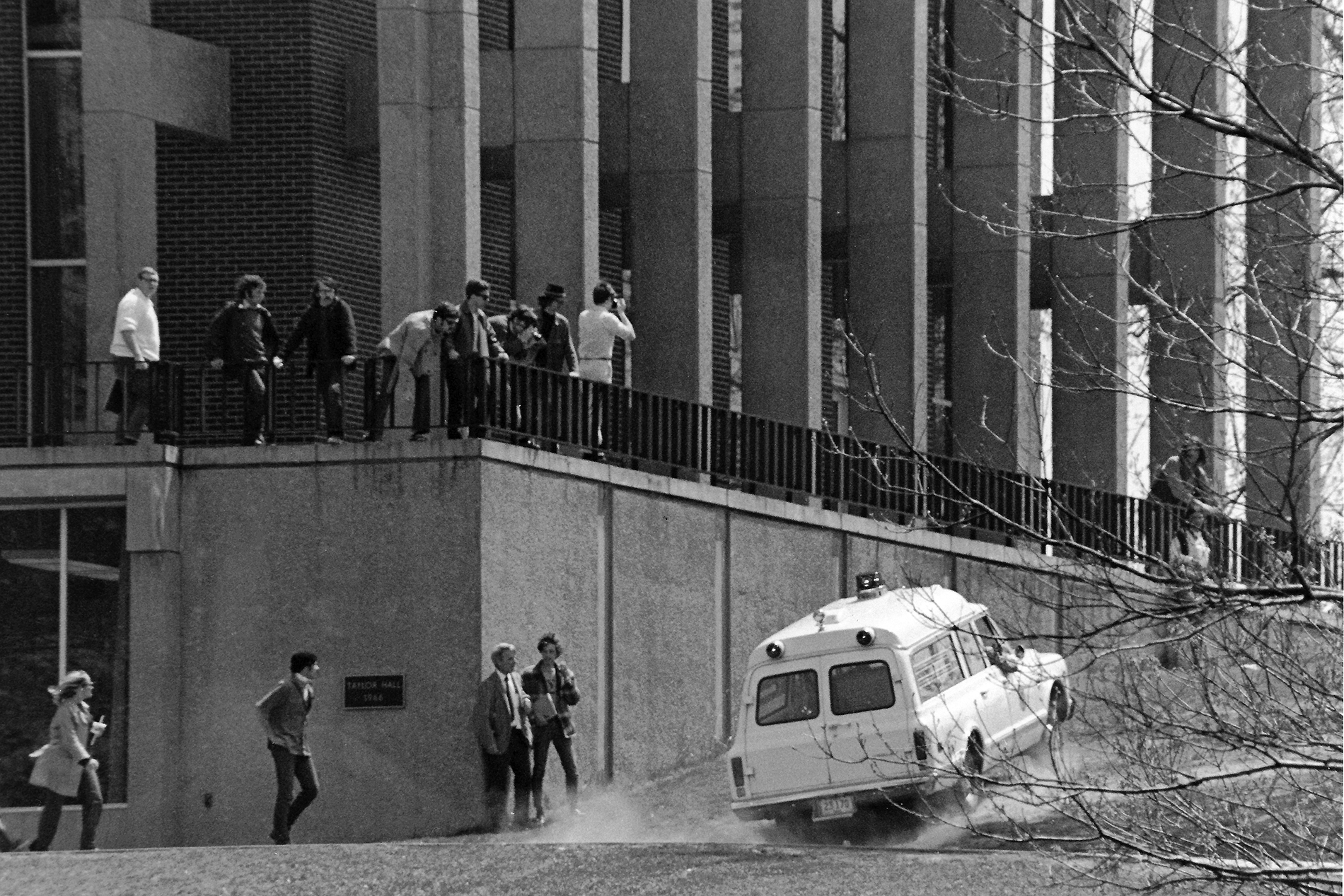

Teenager Mary Ann Vecchio screams as she kneels over the body of Kent State University student Jeffrey Miller who had been shot during an anti-war demonstration on the university campus on May 4, 1970. The protests, initially over the US invasion of Cambodia, resulted in the deaths of four protesters, including Miller, and the injuries of nine others after the National Guard opened fire on students. A cropped version of this image won the Pulitzer-prize. John Filo | Getty Images

It was the face that may, more than anything else, have turned middle America against the Vietnam War.

The photo, taken by John Filo, who won a Pulitzer Prize for it, flooded the media. Front page of the New York Times on May 5. A while later, the covers of Newsweek, Time and Life. Reproduced at one time or another by almost every general-interest publication across the continent.

Perhaps the only photo from the era that rivaled it, in terms of both usage and impact, was the blood-curdling 1968 image of South Vietnamese General Nguyen Ngoc Loan shooting a prisoner in the side of the head.

Kent State emeritus professor Jerry Lewis, 82, was in the crowd that horrible, sunny day in May, serving as a faculty marshal. He was standing a mere 20 yards from Sandy Scheuer, one of the four students killed. When he heard the shots, Lewis, an Army veteran, dove behind a bush.

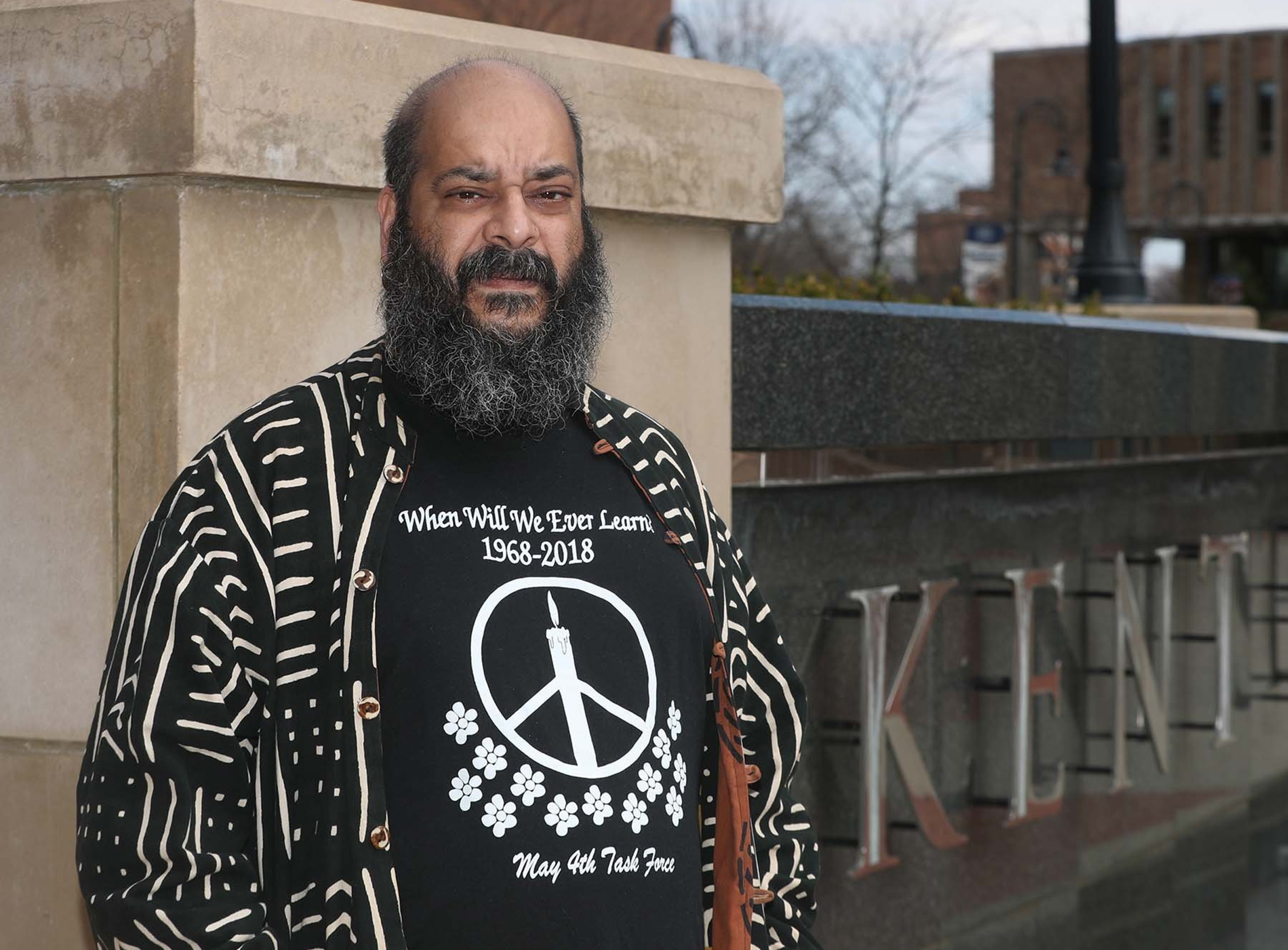

Jerry Lewis, emeritus professor of sociology at Kent State University, talks about what it was like on campus in 1969 during an interview at his home in Hudson. Mike Cardew | Akron Beacon Journal

A sociologist who has written extensively about the tragedy, Lewis compares the drama of the Mary Ann Vecchio photograph to nothing less than Michelangelo’s renowned religious sculpture The Pieta, which portrays the Virgin Mary cradling the dead body of Jesus.

Both the Vecchio photo and photos of the 500-year-old marble sculpture are “framed as pyramids with the top being the heads of two Marys while the bases are outdoor scenes with the earth for the Pieta and the tarmac of a Kent State University parking lot for Jeffrey Miller,” writes Lewis.

“The Mary Vecchio picture shows the shock and horror of the shootings at Kent State by the look on Mary’s face. Next, her upraised hands, as if in prayer, capture the sorrow of the moment. [Michelangelo’s] Mary expresses her grief over the death of her son, not in her face but with her left hand.”

Sitting in his office at the Hudson residence he shares with his wife of 60 years, Diane, Lewis says he believes the photo’s impact was felt internationally.

“The Mary Vecchio photo just grabs you and says, ‘Pay attention.’ ”

But the story of May 4 also was told in words – hundreds of thousands of words, many of them bitterly critical.

Life magazine’s article called the shooting “a senseless and brutal murder at point-blank range.”

Mary Ann Vecchio with John Filo, who won a Pulitzer-prize for the famous photo Vecchio reacting to the death of Jeffery Miller, posing for photographers after their talk during the annual May 4 commemoration program on the Kent State University campus on Monday, May 4, 2009, at Kent State. Paul Tople | Akron Beacon Journal

Newsweek’s story was headlined, “My God! They’re killing us!” and contained this summary:

“The guard insisted that the men fired as they were about to be ‘overrun’ by the students. But if the troops were so closely surrounded, how was it that nobody closer than 75 feet away was hit? And if the rocks and bricks presented such overwhelming danger, how did the troops avoid even one injury serious enough to require hospital treatment?”

Time magazine wrote, “It took [13] terrifying seconds last week to convert the traditionally conformist campus into a bloodstained symbol of the rising student rebellion against the Nixon Administration and the war in Southeast Asia. When National Guardsmen fired indiscriminately into a crowd of unarmed civilians, killing four students, the bullets wounded the nation.”

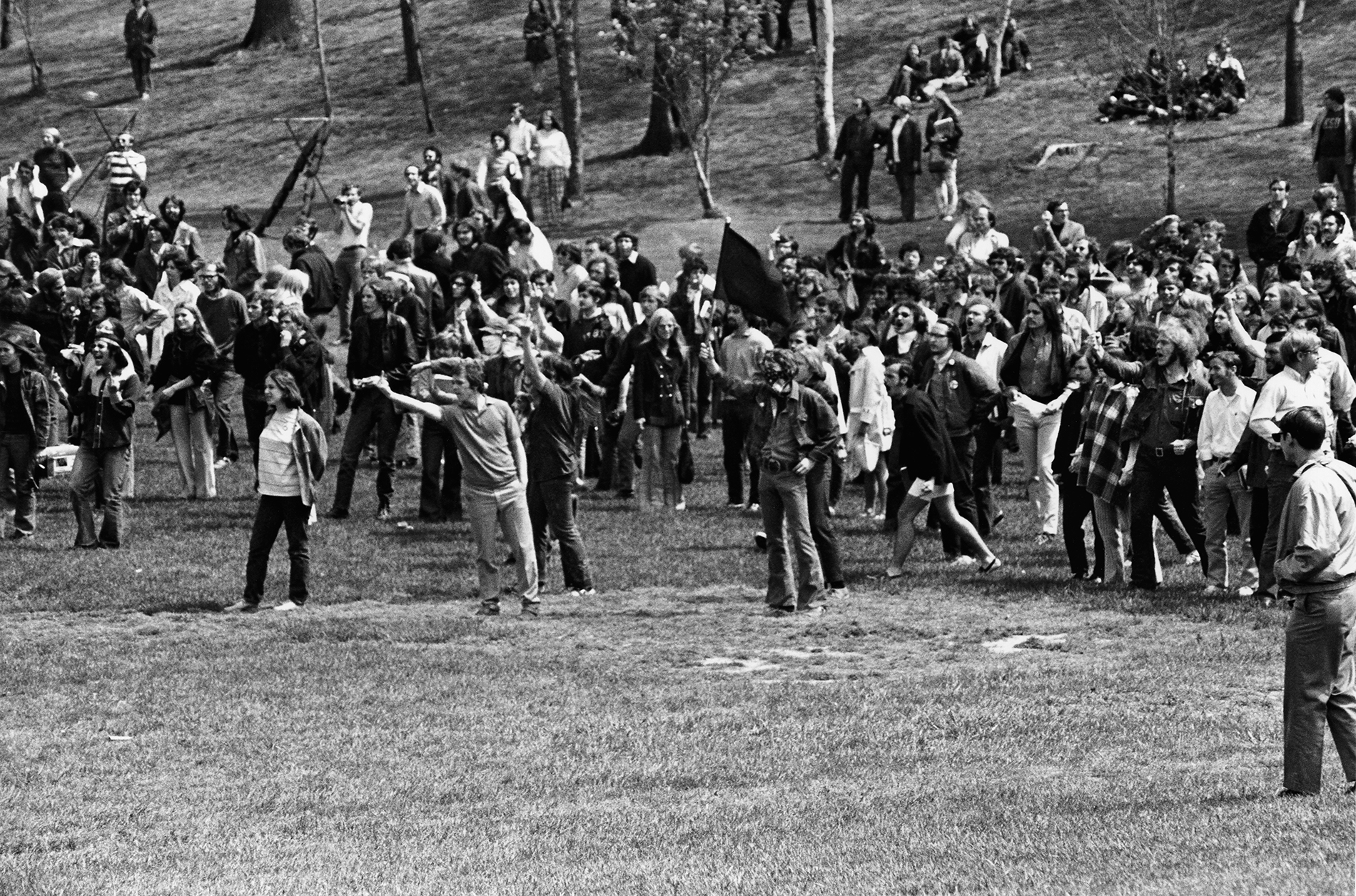

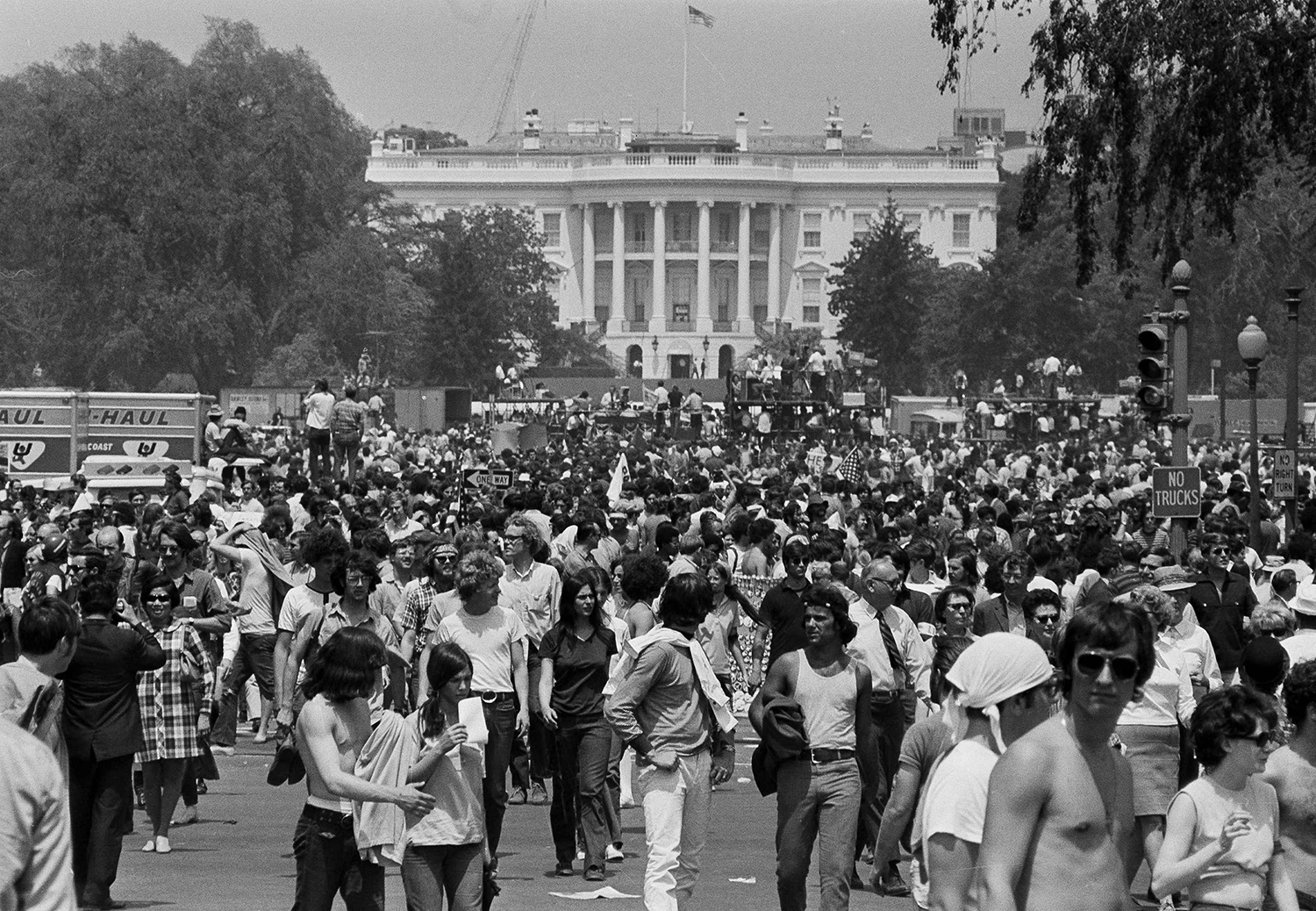

Anti-war demonstrators raise their hands toward the White House as they protest the shootings at Kent State University and the U.S. incursion into Cambodia, on the Ellipse in Washington, D.C., on May 9, 1970. Associated Press | File photo

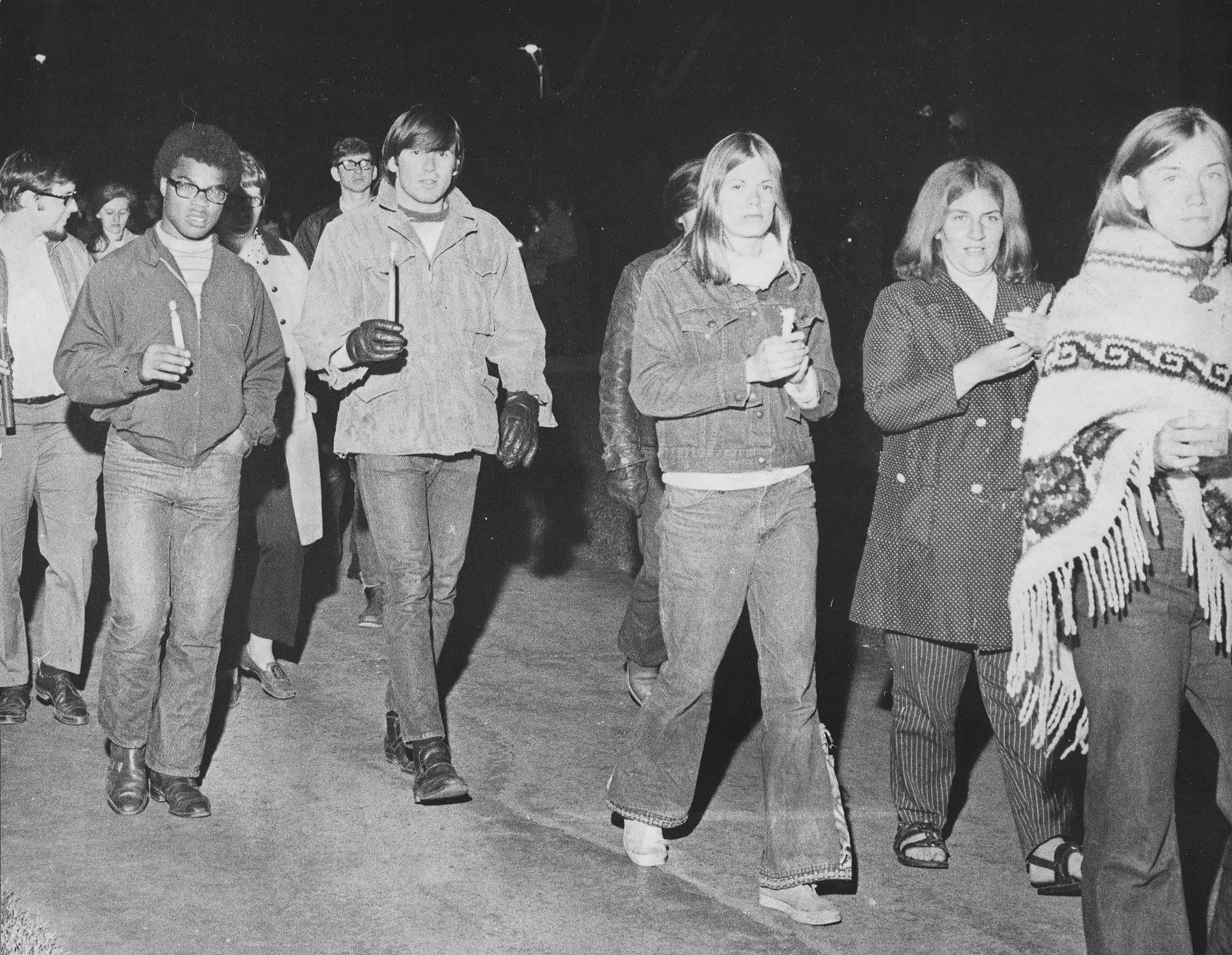

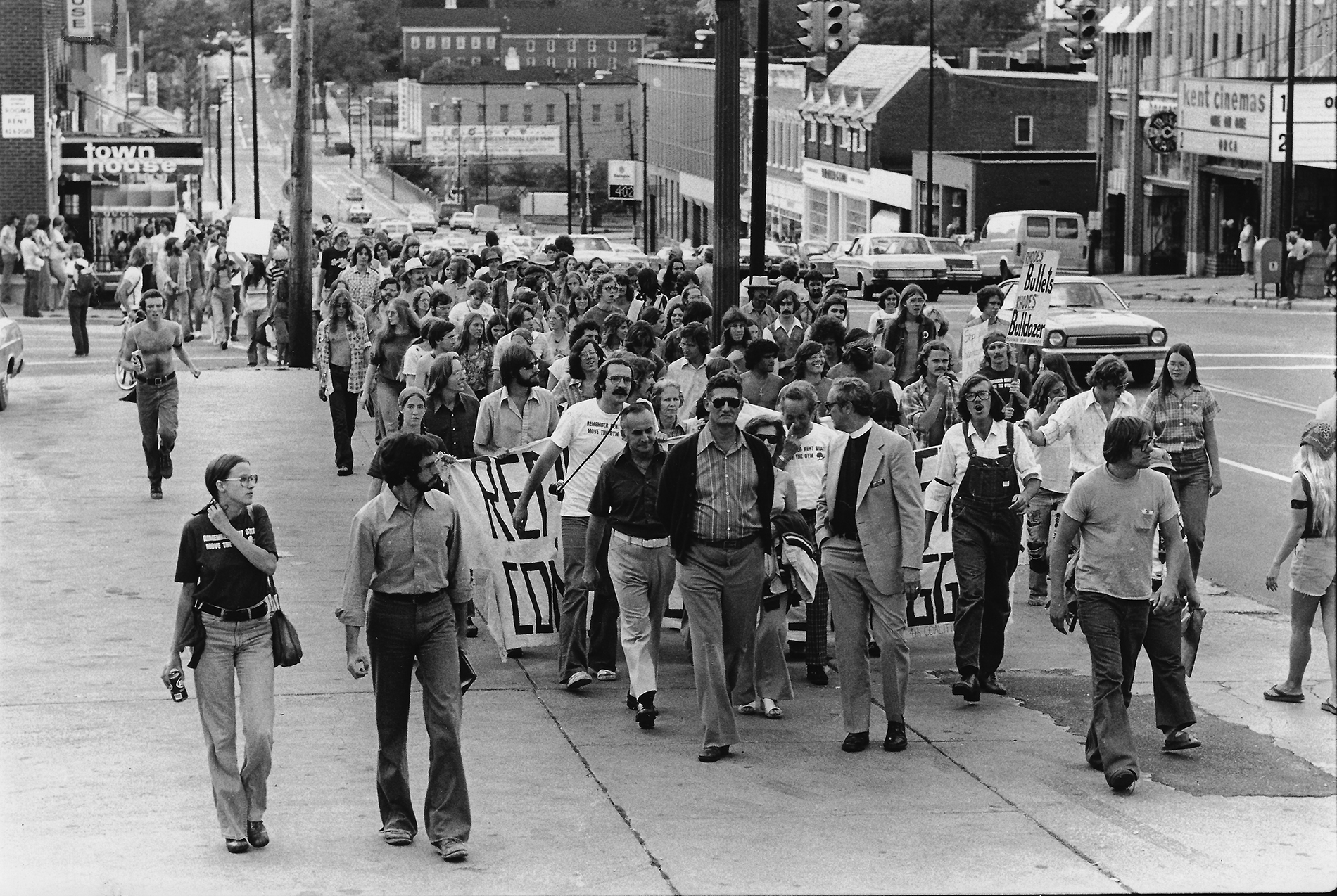

Within days, an estimated four million students went on strike, shutting down hundreds of colleges and universities.

Five days after the shooting, 100,000 people descended on the capital to protest the war.

On May 18, one of the era’s most popular bands, Crosby, Stills, Nash & Young, recorded a song called “Ohio,” which hit No. 14 on the Billboard chart.

Tin soldiers and Nixon coming,

We’re finally on our own.

This summer I hear the drumming,

Four dead in Ohio.

Even the historically conservative Wall Street Journal was unloading on President Richard Nixon a month after the shootings, saying his administration “has not seemed especially concerned about the dangers inherent in the situation to traditions of individual liberty.”

At Jeffrey Miller’s funeral in New York City, attended by almost 5,000 people, famed pediatrician and anti-war activist Dr. Benjamin Spock said the killings “may do more to end the war in Vietnam than all the rest of us have been able to do.”

Across the nation, peace signs were as ubiquitous as today’s smiley-face emojis.

A pro-Nixon war policy demonstration is held by hard hats — or construction workers – and other groups in New York’s financial district, in response to demonstrations against U.S. involvement in Cambodia and the Kent State University shootings, May 20, 1970. Associated Press | File photo

Gallup polls conducted in 1970 showed that 55% of the public believed it was “a mistake” to send troops to Vietnam.

At the same time, however, a powerful backlash was growing against college protests.

In many quarters, Nixon was able to sell the concept that “outside agitators” who were “enemies of the state” were responsible for most campus unrest. His approval rating remained relatively high in the wake of May 4, and two years later, he clobbered his pacifist opponent, George McGovern, in the presidential election.

Nixon’s followers became known as “the Silent Majority,” a phrase he had used in a 1969 televised speech in which he claimed a majority of the population declined to speak out publicly but believed in him and his “secret plan” to end the long, unpopular war.

The considerable public divide that predated May 4 grew vastly wider immediately after the shots were fired.

Many folks jumped on the fact that the girl in the famous photo was not a Kent State student, but a 14-year-old runaway from Florida, seemingly confirming Nixon’s claims.

But as professor Lewis points out, every person killed or wounded by the National Guard, as well as every person later indicted for criminal activities that weekend, was directly tied to the university, either as a registered student or a faculty member.

Nixon himself realized the gravity of Kent State – and the role he played in it.

On May 1, the day after he sent troops into Cambodia, widening the war he claimed to be winding down, he was leaving the Pentagon when he said, “You see these bums, you know, blowing up the campuses.

“Listen, the boys that are on the college campuses today are the luckiest people in the world, going to the greatest universities, and here they are burning up the books, storming around about this issue [invading Cambodia]….

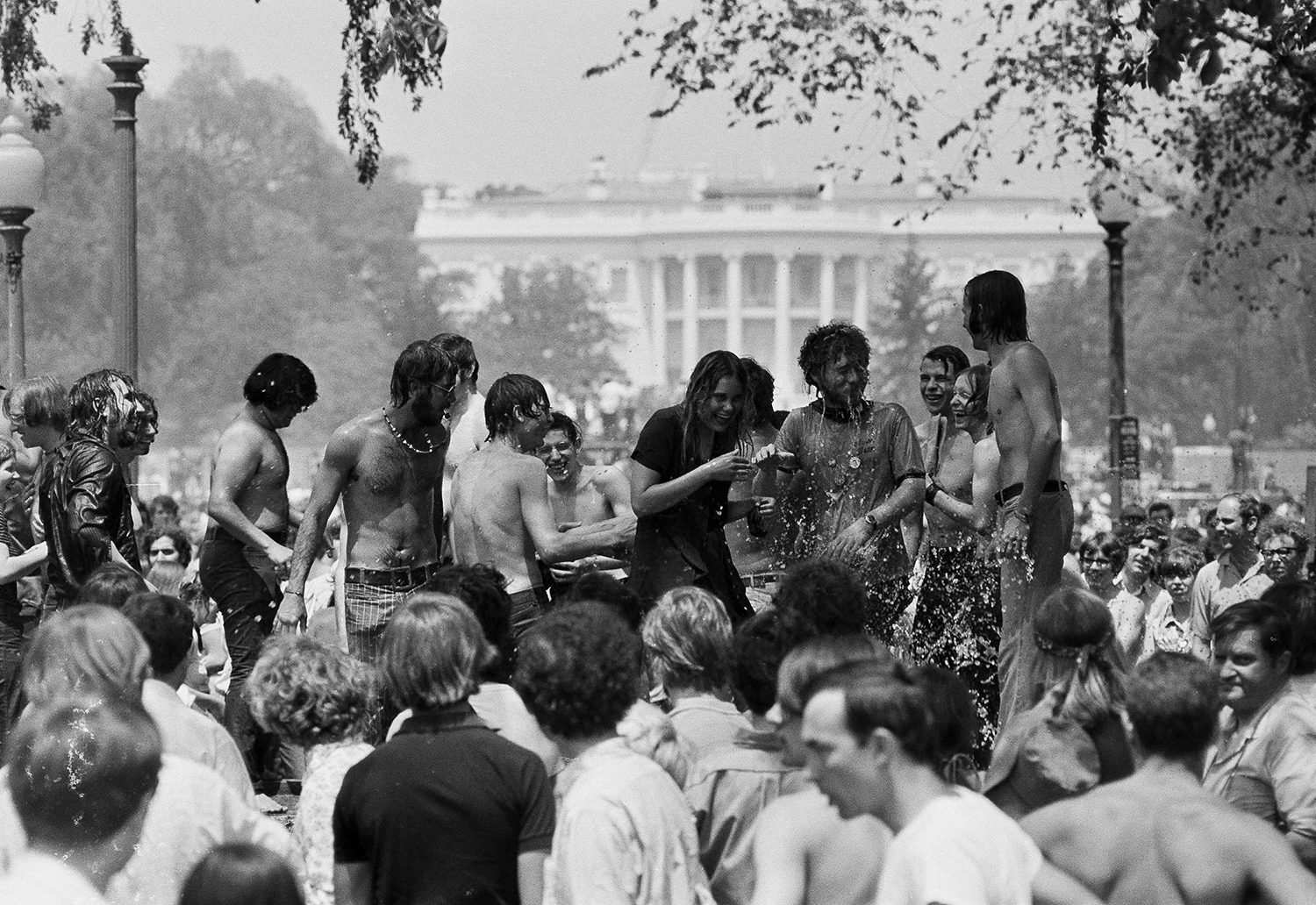

The water flies as young people clown a bit in the 88 degree weather during an anti-war demonstration on the Ellipse in Washington, D.C., on May 9, 1970. The demonstrators were protesting the shootings at Kent State University and the U.S. incursion into Cambodia. Associated Press | File photo

“Then out there [in Southeast Asia] we have kids who are just doing their duty. They stand tall and they are proud … and we have to stand in back of them.”

Nixon’s chief of staff, H.R. Haldeman, secretly kept a detailed diary of his interactions with the president that was published by Haldeman’s wife shortly after his death in 1994. Haldeman made this entry the day of the shootings:

“[Nixon is] very disturbed. Afraid his decision set it off…. Issued condolence statement, then kept after me all the rest of the day for more facts. Hoping rioters had provoked the shooting but no real evidence they did….

“Obviously realizes, but won’t openly admit, his ‘bums’ remark very harmful.”

Ohio Gov. Jim Rhodes was at least as culpable in fanning the flames. He arrived on campus May 3, and in a news conference attributed campus violence to students who were “worse than the Brownshirts and the Communist element and also the Night Riders and the vigilantes. They are the worst type of people that we harbor in America.”

Perhaps the best insight into Nixon’s general outlook on Kent State was revealed just last year by journalist Bob Woodward, who was speaking on campus on the 49th anniversary.

A researcher going through the voluminous collection of secret Oval Office tapes archived at the University of Virginia discovered a portion where Nixon and Haldeman were discussing the Attica prison riot, which left 29 inmates dead.

Nixon: “You know what I think? This might have one hell of a salutary effect. You know what stops them? Kill a few.”

Haldeman: “Sure.”

Nixon: “Remember Kent State? Didn’t it have a hell of an effect?”

It certainly did. It also had a fatal effect on Nixon’s career.

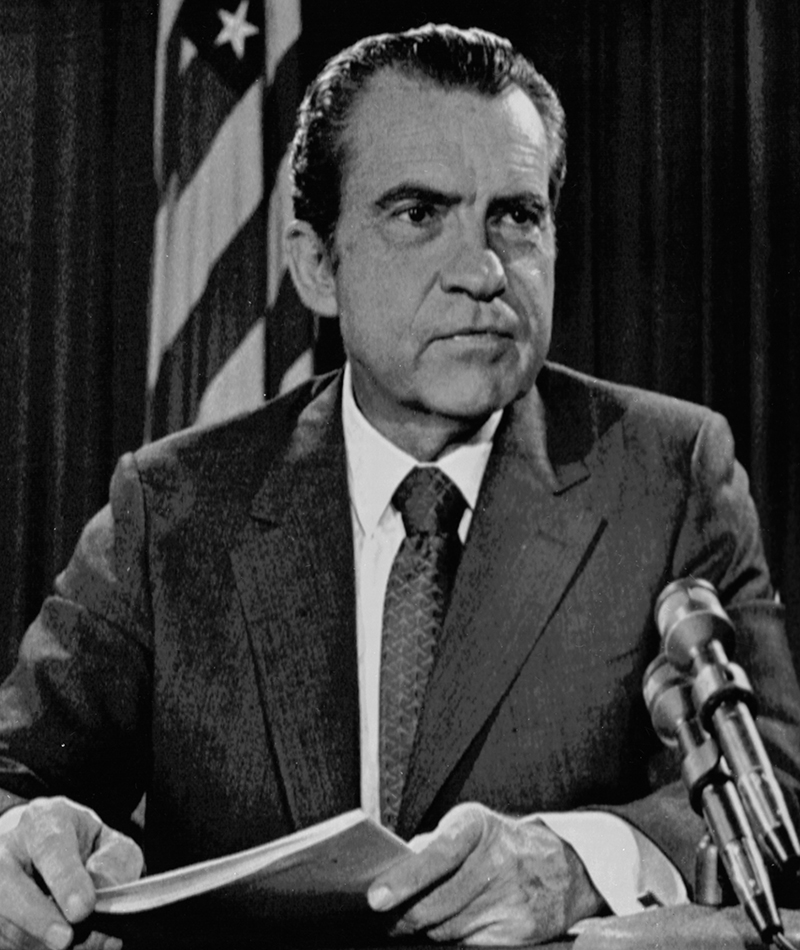

American President Richard Nixon poses for pictures in his White House office, on Aug. 15, 1971, after a nationwide television speech which dealt with economic policies. Associated Press | File photo

In his 1978 book “The Ends of Power,” Haldeman wrote that Kent State “marked a turning point for Nixon, the beginning of a downward slide toward Watergate.”

Those 13 seconds of gunfire 50 years ago changed the course of American history.

Bob Dyer can be reached at 330-996-3580 or bdyer@thebeaconjournal.com. He also is on Facebook at www.facebook.com/bob.dyer.31.