Kent State shootings on May 4, 1970, still shape Ohio colleges 50 years later

Mark Ferenchik, The Columbus Dispatch

April 30, 2020

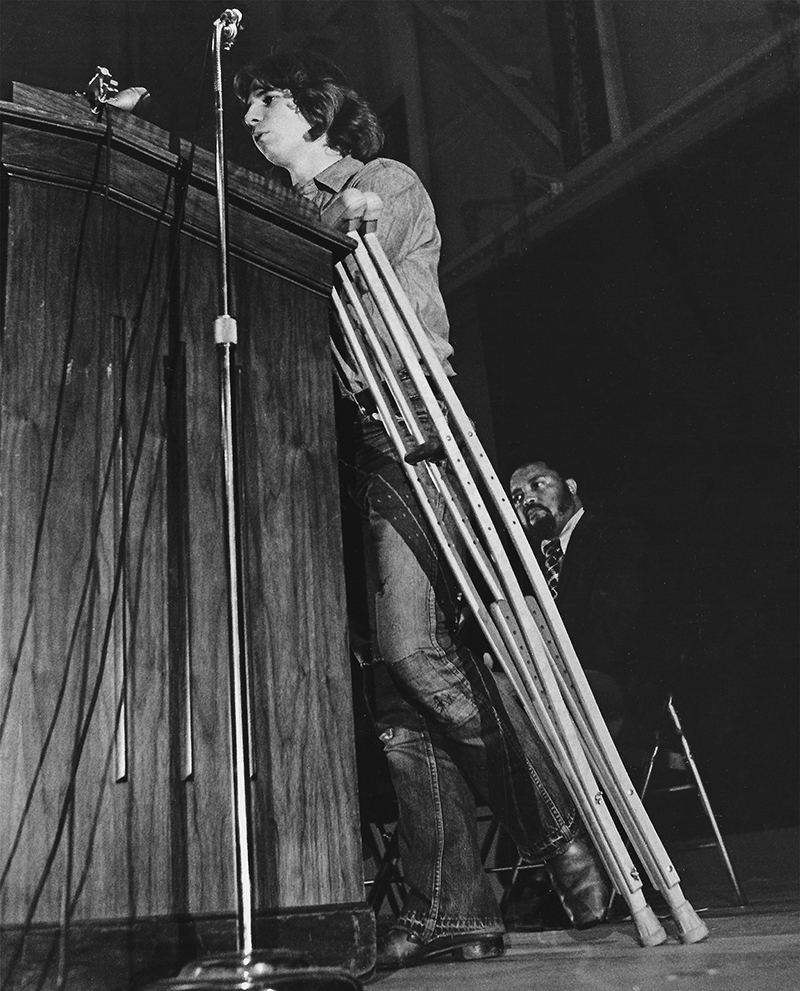

Thomas Hodson was an associate editor at The Post, Ohio University’s student newspaper, in May 1970. He was about to graduate and was ready to head up Route 33 to Ohio State University in Columbus to go to law school.

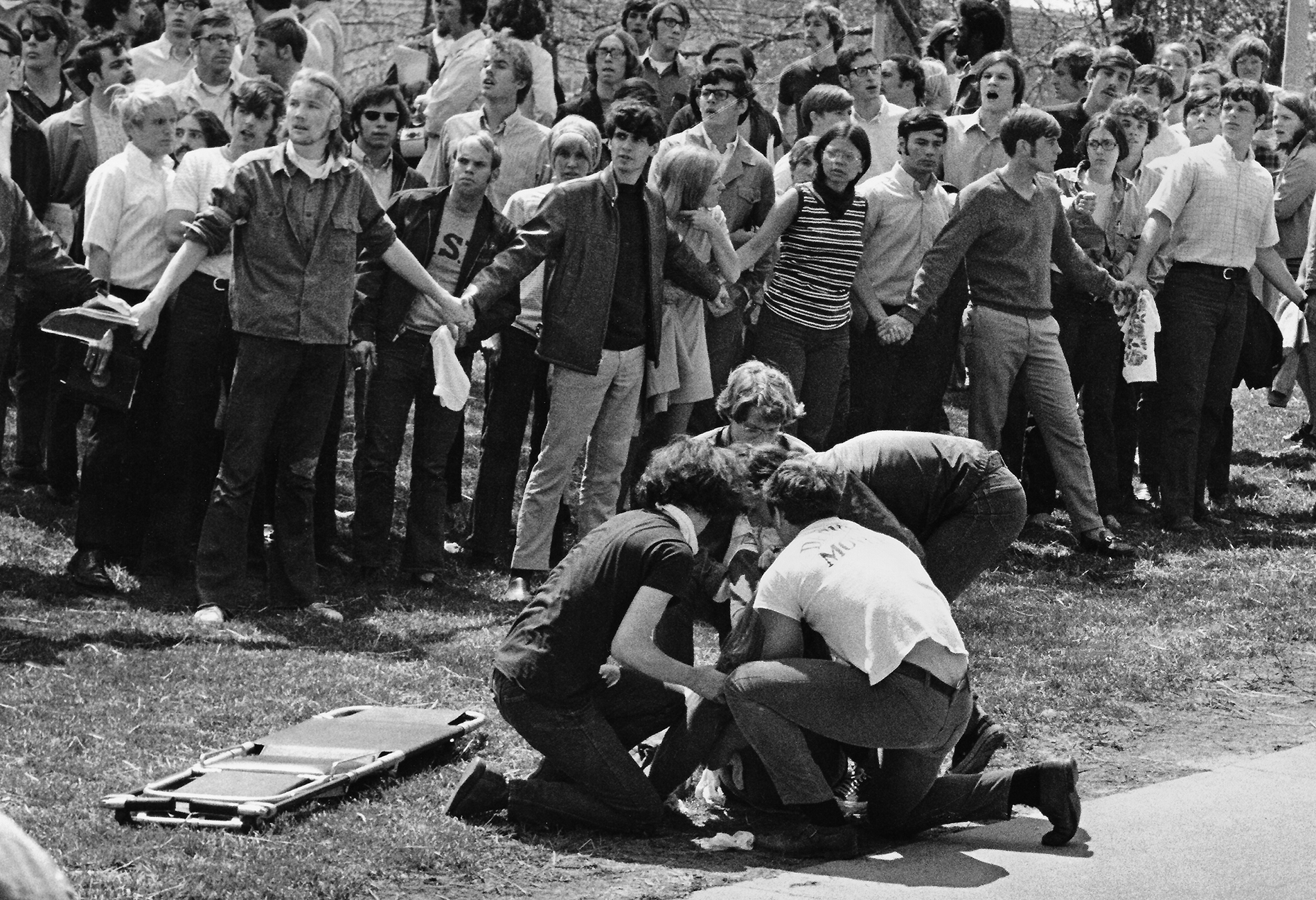

He was in class in Athens on May 4, 1970. News was spreading about the shootings that had just happened at Kent State University, a three-hour drive to the north.

Hodson went to the Post’s office and found out immediately what had happened.

“It was a sick feeling. It was like everything had been building to a crescendo,” he said. “This was not the crescendo that we expected.”

It was a crescendo that reverberated across the state and country, but especially at other college campuses across Ohio, some already charged with unrest because of the unpopular war in Vietnam.

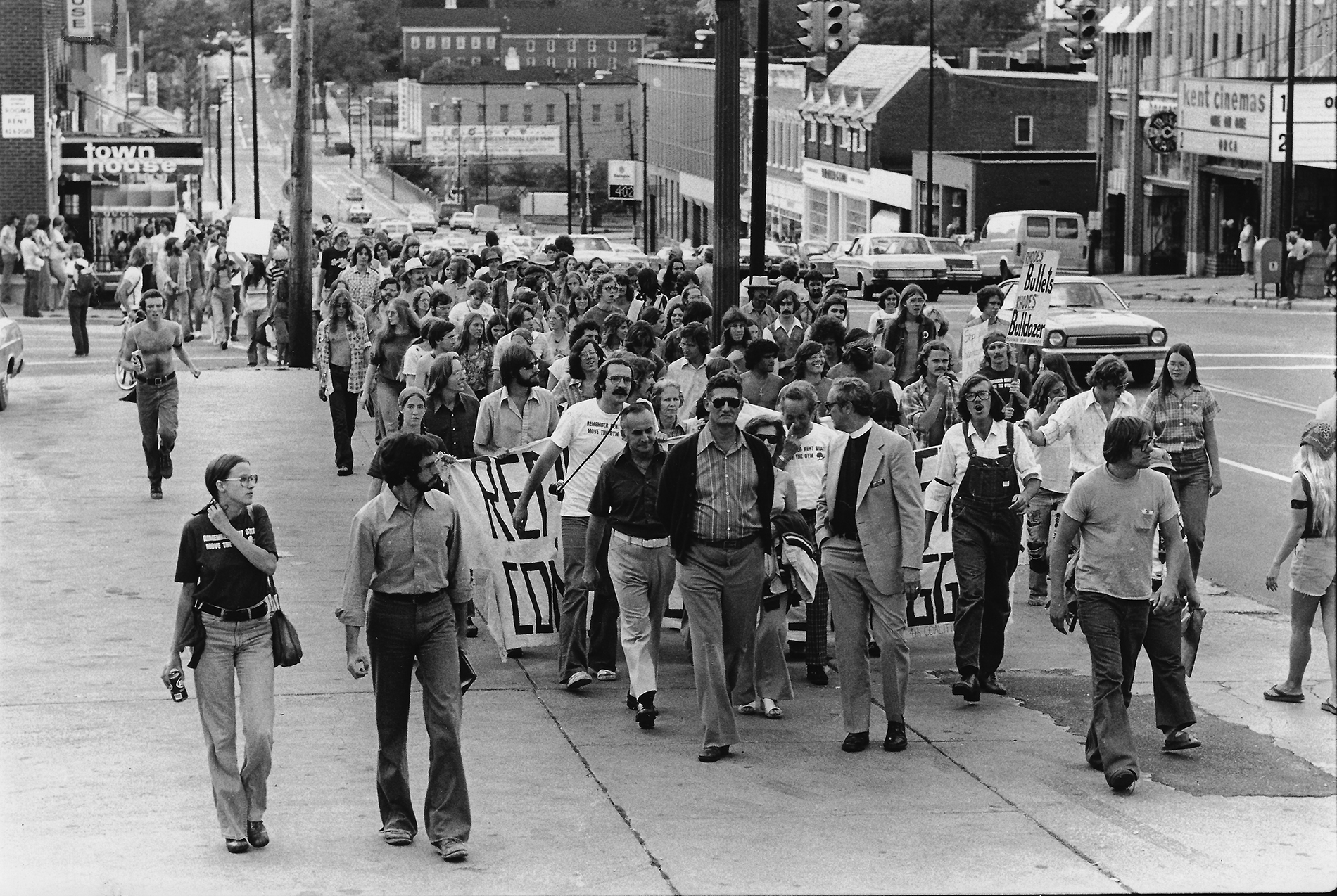

Demonstrations had broken out at Ohio State in late April. Ohio University students protested later in May. Universities across Ohio and the country eventually shut down following the Kent State shootings.

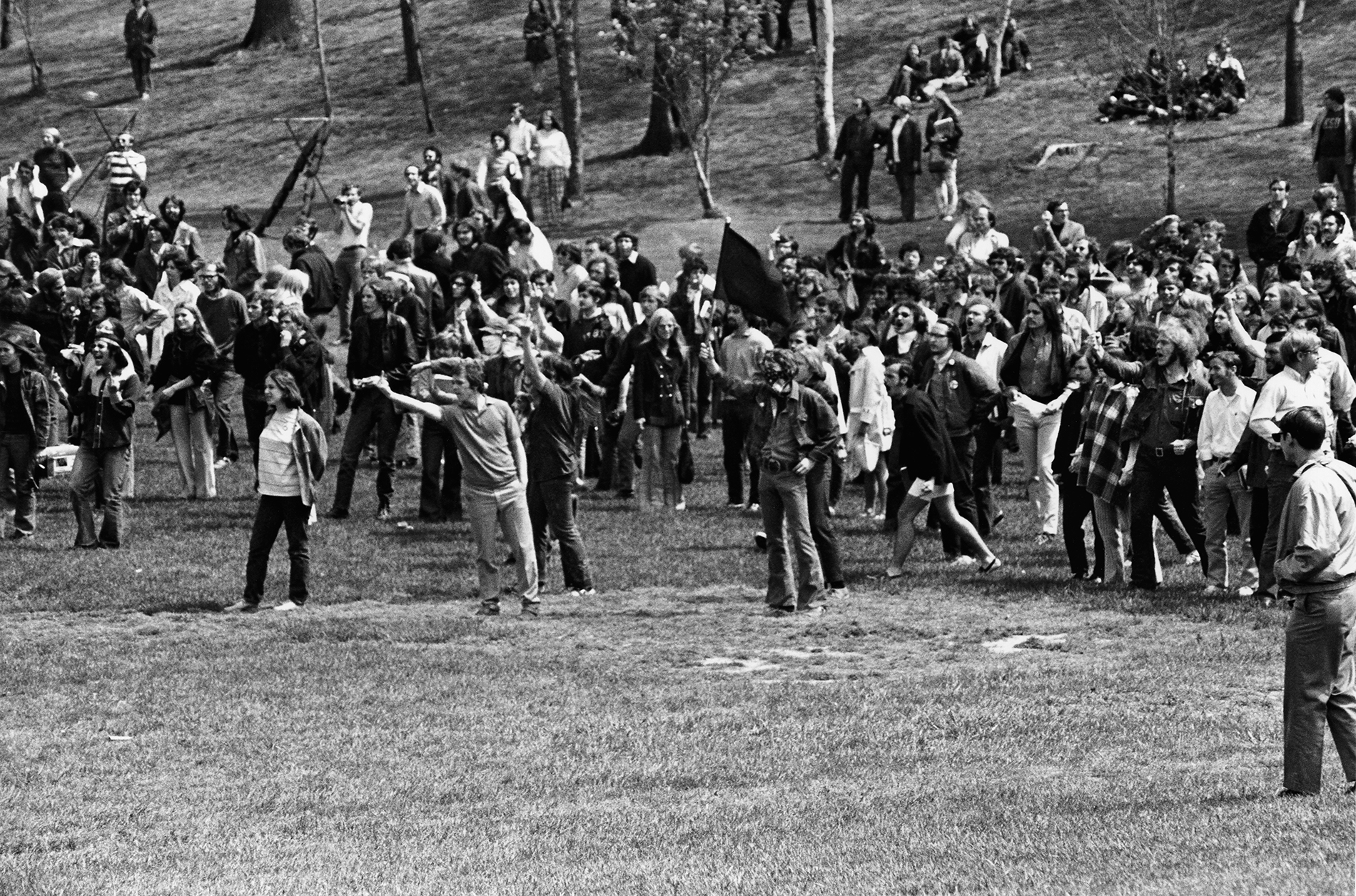

Crowds line the Ohio State University intramural fields as ROTC units are reviewed and protesters join a march on May 6, 1970, two days after four students were killed protesting the Vietnam War at Kent State University. File photo | The Columbus Dispatch

While the short-term effects of May 4 were clear, there were long-term effects for Ohio universities and for the students who populated them.

It changed the way universities and their communities interacted. It prompted changes in state law regarding campus protests and violence. Some universities enacted more controls on events.

And the shootings spurred people to action.

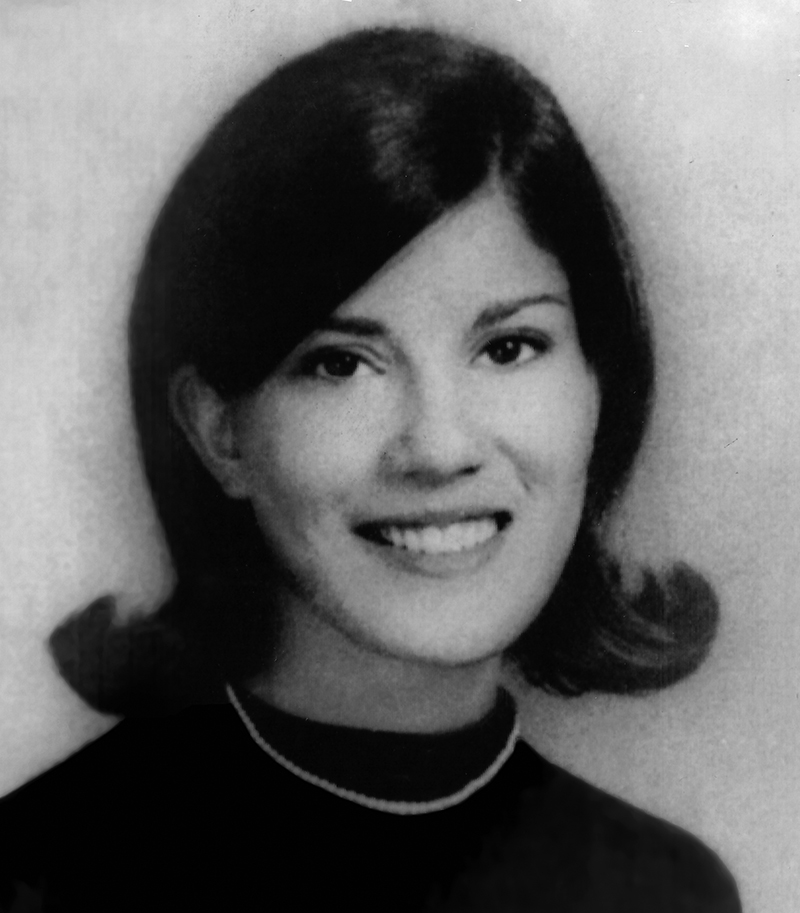

David Leland, now a Democratic state representative from Columbus, was a high school student living in Kansas when Jeffrey Miller, Allison Krause, Sandy Scheuer and Bill Schroder were killed at Kent State.

He and his family were about to move to Columbus, where his father had accepted a position as a professor of psychology at Ohio State and helped put together the university’s Nisonger Center, which works with people with developmental disabilities.

Leland said his high school friends were worried about him moving to Columbus.

“’What kind of state are you moving to?” Leland said his friends asked. “They were just frightened for me moving to a state that was shooting college kids on college campuses.”

Leland already strongly opposed the Vietnam War. What happened at Kent State spurred him toward activism even more.

Obviously the war was a tremendous rallying point for all of us. Kent State was just an example of how bad it could get; how bad society was moving in relationship to the war.

“Obviously the war was a tremendous rallying point for all of us,” Leland said. “Kent State was just an example of how bad it could get; how bad society was moving in relationship to the war.”

He ended up working for the campaigns of two Democrats: Howard Metzenbaum for the U.S. Senate and John Gilligan for governor. He worked to seat more younger, progressive people on the Franklin County Democratic Party’s Central Committee. And ultimately, he ran for political office.

Bill Shkurti, a 1968 graduate of Ohio State and the university’s former senior vice president for business and finance, wrote a book in 2016, “The Ohio State University in the Sixties: The Unraveling of the Old Order.”

“The Kent State shooting was a bookend example of law and order getting out of hand,” said Shkurti, who was in an Army artillery unit in Germany on May 4, 1970.

“The most immediate impact was the universities changed with how they deal with students,” Shkurti said. OSU was caught off guard to a degree with how much students were upset, he said.

On April 30, 1970, President Richard Nixon announced the expansion of the Vietnam War into Cambodia. Students protested.

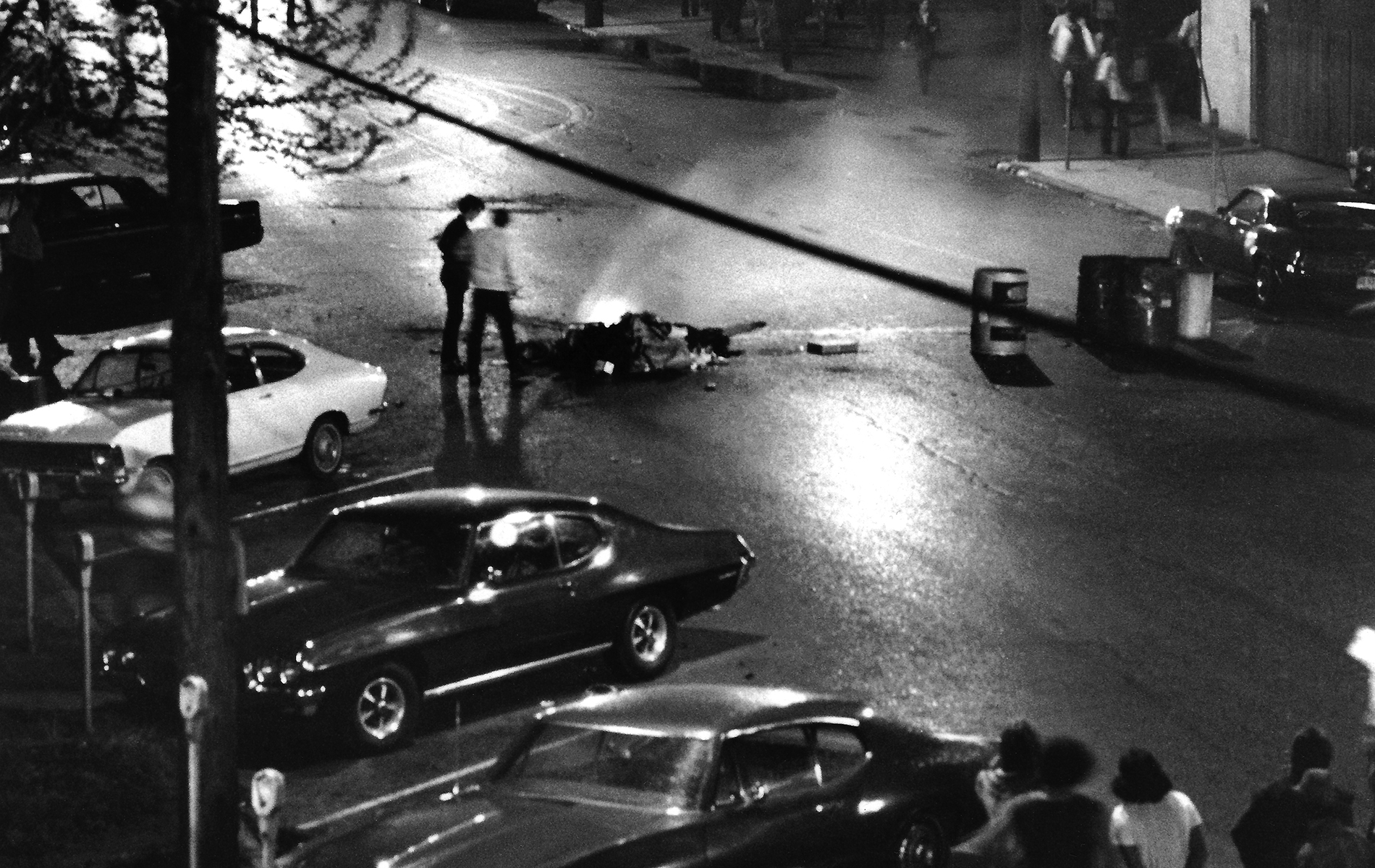

That same day about 2,000 students – The Dispatch called them “young rowdies” – clashed with Ohio National Guardsmen in front of the Ohio State Administration Building and on the Oval. A number of demonstrators were arrested, with some shouting, “Pigs off campus” and “Pigs go home.” Police imposed an 8 p.m. curfew on campus that Thursday.

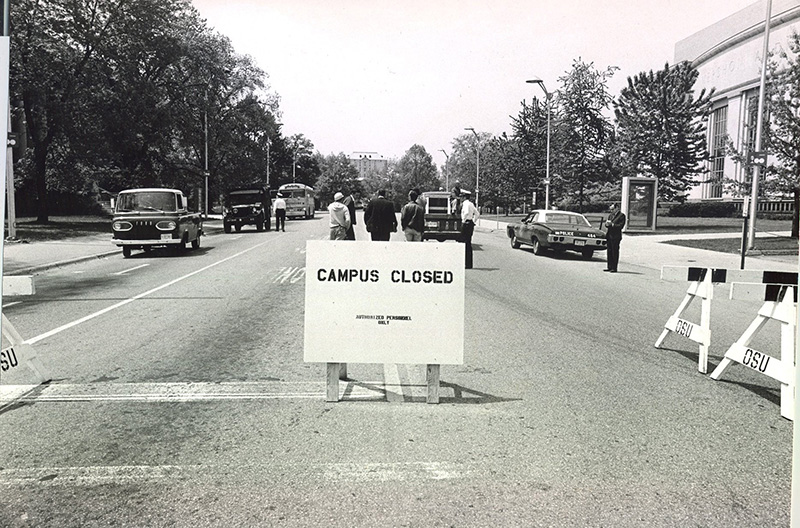

Police, guardsmen keep the Ohio State campus closed and sealed on May 8, 1970, after four students were shot and killed by the Ohio National Guard at Kent State on May 4, 1970. File photo | The Columbus Dispatch

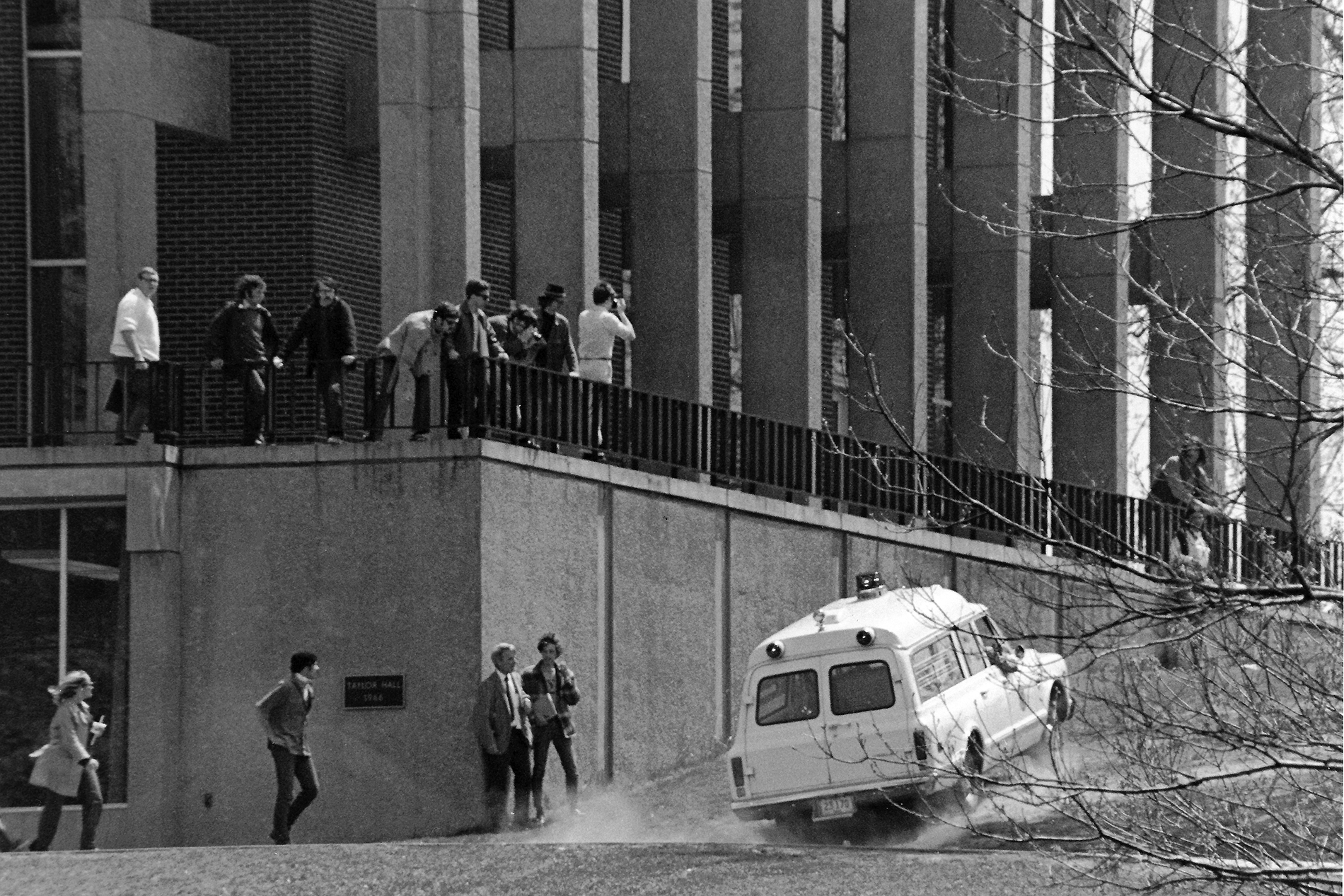

After more demonstrations following the May 4 shooting, OSU President Novice Fawcett on May 6 shut down the campus that at the time served 45,000 students.

Andy Alexander recalled when Ohio University officials closed the Ohio University campus, but that wasn’t until a week after Ohio State’s closure.

Alexander, 71, a journalist and former Washington Post ombudsman, vividly remembers May 4.

“There had been demonstrations on campuses through Ohio,” said Alexander, who was the editor of the student paper. He added that students were trying to keep the OU campus peaceful so as not to give politicians a reason to close campus.

He said local police were increasingly under pressure by people in the community to crack down on student protests.

“There was really the prospect of vigilante violence,” said Alexander, though he said he personally did not feel threatened.

By May 14, things had deteriorated to the point where about 1,000 students battled with police, leading to 26 arrests and the closure of the Ohio University campus, he said.

“I think Kent State accelerated the anger and student protests,” he said.

Hodson, now 71 and director of WOUB Public Media and Joe Berman Professor of Communication at Ohio University’s Scripps College of Communication, said he believes what happened in 1970 led to a decline in enrollment at Ohio University.

The student population in 1970-71 ticked up a little to 19,314, but decreased to a low of 12,814 in 1975-76, before rising again, to 14,209 in 1980-81, and 17,630 by 1990-91.

“They had to mothball dormitories,” Hodson said. “Mom and pop were not going to send their kids to a place that rioted.”

Hodson ran for municipal court judge in Athens in 1979 and won. Between 1970 and then, he said the community began to realize that it didn’t want a police force that was out of touch and belligerent.

“Police started doing a lot more training, interpersonal relationship training,” he said.

Front pages from the Columbus Evening Dispatch in May 1970 reported the closure of Ohio State’s campus following the shootings at Kent State.

Police in Athens in past years have often dealt with crowds of Halloween revelers.

“They’ve learned how to deal with large crowds and festivals. They still make arrests. But there’s not a confrontation,” he said.

That changed the way police think. “That’s been a change that has continued,” he said.

Hodson was also an Ohio University trustee from 1989 to 1998. He saw more of a working partnership between Athens and the university.

Shkurti said one thing the Ohio State protests led to was a decision to have two students as voting members of the board of trustees. “There’s a seat at the table for that, bringing dissent in house rather than out on the streets,” he said.

Bruce Johnston, the president of the Inter-University Council of Ohio, which represents the state’s 14 public universities, said the emphasis is now on respecting the rights of students to speak.

But a university’s educational mission can’t be compromised, he said. Also, the right to express opinions is not the right to destroy property, Johnston said.

The Ohio General Assembly addressed student demonstrations after the Kent State shootings.

The campus disruption law, Ohio House Bill 1219, was signed into law in June 1970. It gave universities the authority to remove students, faculty or staff members “so that law and order are maintained.” Schools can limit access to campuses, impose curfews and suspend or expel students who violate rules.

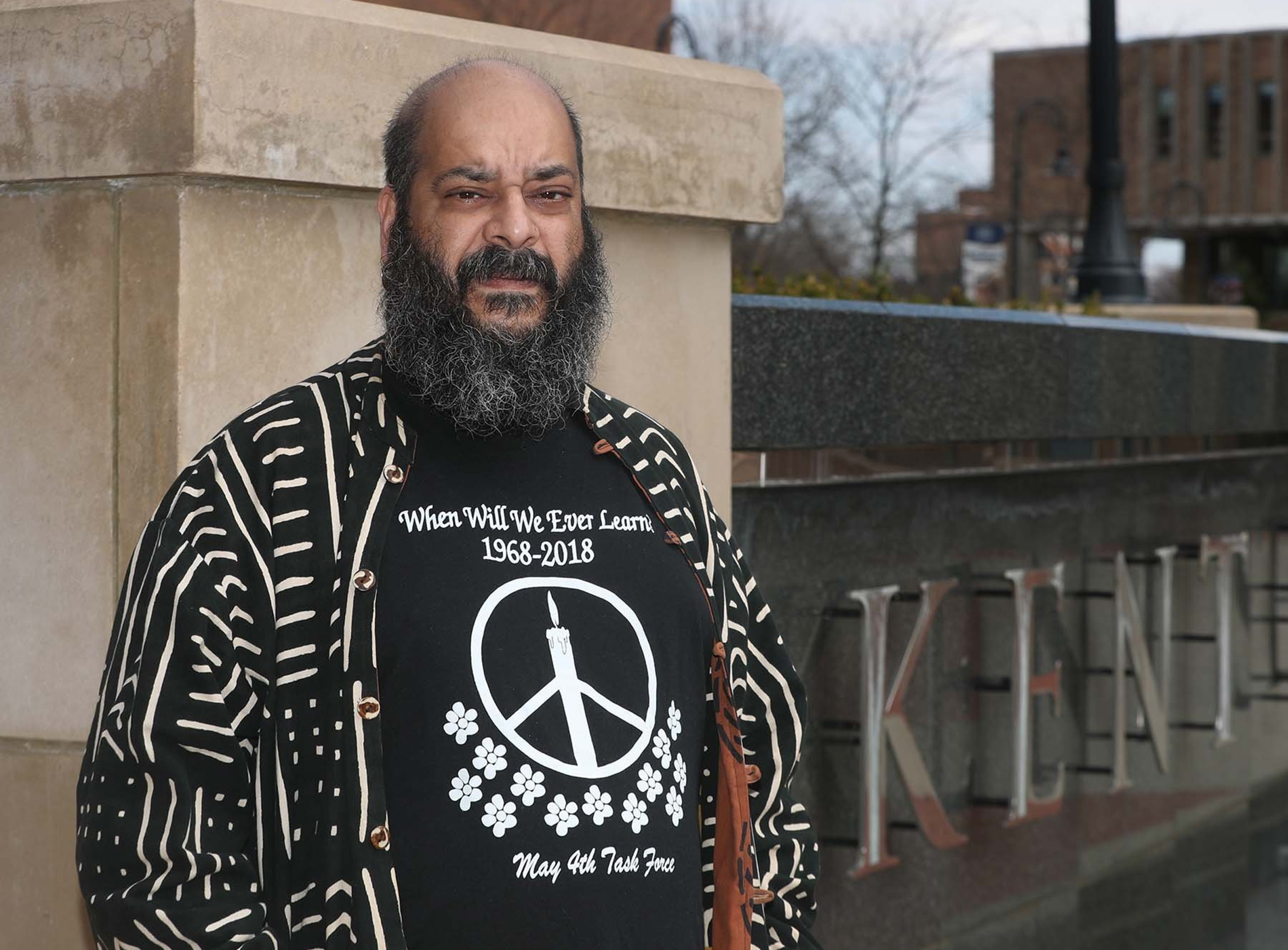

The website of Kent State’s Office of Student Conduct says the purpose of the law is to “protect university students, faculty, staff, and other members of the campus community from crimes of violence committed in the vicinity of the university or upon people or property at the university.”

At the University of Akron, Susan Ramlo, a professor of general technology and physics, said it’s hard to connect recent actions regarding students’ right to speak to what happened at Kent State 50 years ago. She said some schools may not want too much free speech.

Ramlo, who is vice president of the Akron chapter of the American Association of University Professors, said how universities react now is more about the corporatization of universities, with boards of trustees often filled with business people.

They look at freedom of speech on campus as a problem. They don’t want publicity.

“They look at freedom of speech on campus as a problem. They don’t want publicity,” Ramlo said.

When members of Wright State University’s faculty union went on strike last year, Akron students and faculty protested on the University of Akron’s campus.

“There were guidelines. The university told us where we could set up, what we could do,” Ramlo said. “It was meant to maintain order on campus.”

University of Toledo Police Chief Jeff Newton said he works with groups who want to demonstrate.

Good relationships and dialogue maximize the probability that events go smoothly, he said.

An unidentified demonstrator at Ohio State University defies the Nation Anthem and doubles her fist as members of the school’s ROTC unit salute during ceremonies. May 5, 1970. File photo | The Columbus Dispatch

“Generally speaking, we haven’t had anything we felt we couldn’t handle,” he said. But he said he doesn’t know that an event five decades ago plays a role in how he deals with demonstrations.

Leland called the Kent State shootings “a terrible moment in American history.”

“But it’s been 50 years,” said Leland, wondering if May 4, 1970, is just a historical marker for many people today.

Alexander said there are larger lessons too.

“One lesson for young people is that there’s a time in your life when you think the world is coming apart,” he said. “It hasn’t. There’s always a brighter day on the horizon.”

Gannett Ohio and Columbus Dispatch Reporter Mark Ferenchik can be reached at mferench@dispatch.com or @MarkFerenchik.