FULL CONTACT

How a lifetime of football blows ended in tragedy for Jevan Snead

Jevan Snead and the Longhorns feel the pain of a 12-7 loss to Texas A&M in 2006. [Jay Janner/AMERICAN-STATESMAN]

On a muggy April evening, Corey Kenyon sat on his back porch with his high school football buddy Jevan Snead, cooking steaks on the grill, listening to the buzzing cicadas and reminiscing about their glory days on the field. It was one of their usual trips down memory lane.

For 15 years, even as Jevan Snead’s football career took him to the heady heights of NCAA stardom and the crushing lows of NFL flops, the Stephenville High School stars had remained close.

But as they reminisced that night, Kenyon recalled, something was amiss with his friend. As he recounted the smacking of helmets, the pileups of pads and the thunderous applause of fans watching their stunning plays, Snead sat expressionless.

“He just kind of laughed, like a weird, stressed-out kind of laugh, and said, ‘I don’t remember any of that kind of stuff,’ ” said Kenyon, now a Cedar Park Middle School assistant football coach. “It was like, ‘What are you talking about?’ And I would say, ‘That was one of our best games. You did this and this and this.’”

Kenyon brought up the 2010 Cotton Bowl. As quarterback for the University of Mississippi, Snead came back from a skull-jarring helmet-to-helmet collision that left him dazed on the turf and led his team to a 21-7 victory over Oklahoma State. The game was a highlight of Snead’s career.

“He was just like, ‘I don’t remember it,’ ” Kenyon said.

The words were worrisome. Football had been his friend’s life. He spent most of his childhood, teen and college years on a path to football stardom, devoted to a sport that had made him a top national recruit and had given him a ticket out of small-town Texas. He was a two-time all-state performer at Stephenville before landing at the University of Texas.

Hoping for a bigger role on the field, he transferred to Ole Miss in 2007. By the time he left three years later to enter the NFL draft, the dark blond-haired, blue-eyed football player was so popular that he was often asked to sign autographs or have game-day pictures taken with fans in the university’s picturesque tailgating mecca called the Grove.

But nearly a decade after the peak of Snead’s football career, his family and close friends believe the sport he so dearly loved unraveled him. By his early 30s, he fought symptoms of dementia, struggled with depression and could scantly recall mundane details of the previous day or even the thrill of bygone victories.

Snead’s post-football descent deepens questions about the dangers of a beloved American pastime and what experts say routine head trauma does to the brains of young players weekend after weekend during football season. It has put the issue of chronic traumatic encephalopathy, known as CTE, on center stage for Snead’s loved ones, who have now devoted themselves to educating parents and youths about the dangers and the need for top-line safety gear.

Snead’s family — his father, mother and two siblings — believes he suffered a series of concussions throughout his life, from when he was a rough-and-tumble boy in rural Texas crashing into live oak trees to the infamous Cotton Bowl helmet-to-helmet impact captured on national TV.

Snead himself was so certain that he suffered from CTE that he instructed his family to donate his brain to medical research after his death.

A photo of Jevan Snead hangs on the wall of coach Chad Morris’ office near some trophies Snead helped win in 2005 at Stephenville High School. [Jay Janner/AMERICAN-STATESMAN]

Childhood to the Cotton Bowl

Jevan Snead was about 6 when his father realized that the middle of his three children was a gifted athlete. Not only did he have a strong right arm, but he was intensely competitive.

Over the next two decades, Jaylon Snead would become his son’s greatest fan. The two piled into his king-cab Ford pickup to drive to sports camps across Texas. When Jevan went off to college, his father crisscrossed the Southeast on weekends and never missed a game. His Twitter handle is @quarterbackdad.

Jaylon Snead, who managed a ranch in Concho County before becoming a school bus driver, says he first thought his son would become a baseball player. His skills were apparent the first summer he took Jevan from their home in Eden to a camp 90 miles away at Hardin-Simmons University in Abilene when he was 7. By the time he was 10, coaches clocked him throwing a baseball at 62 miles per hour.

“He was just a thrill to be around athletically,” Jaylon Snead said.

But Jevan was more interested in football. The summer between the third and fourth grade, his father began driving him 45 miles to San Angelo for after-school practice and Saturday games as part of a peewee football league. They were often so pressed for time that Jevan changed clothes in his father’s truck between school and practice.

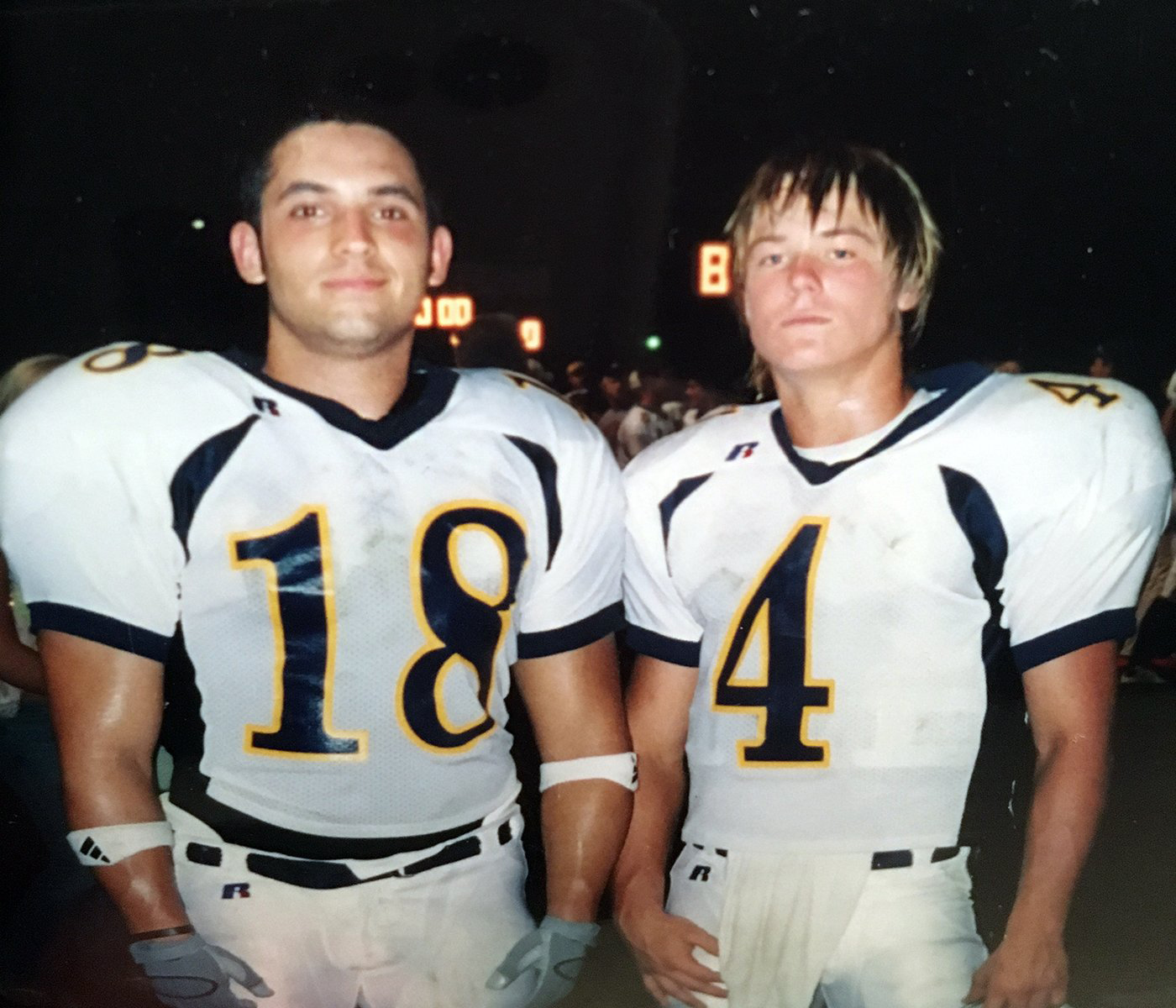

Corey Kenyon, left, with Stephenville teammate and best friend Jevan Snead, is now a coach in Cedar Park. [Contributed]

“He came to football naturally,” Jaylon Snead said. “The first day he went to practice, they did a tackling drill, and he planted his face mask right in the chest of the fella he was tackling. The coach just backed up and said, ‘Oh, my gosh. We have a player here.’ ”

Snead was No. 9 with the San Angelo Apaches through the sixth grade.

“He was eager,” peewee coach Art Rangel recalled. “Football was his life back then, and we knew he was meant to go to bigger and better.”

Jevan played junior high football in Eden, a town of about 1,200 people who began rallying around the young standout. His father’s voice cracked when he remembered the local banker stopping him one night after a game.

“He put his arm on my shoulder, and he said, ‘Jevan has always been known as Jaylon’s boy. But it won’t be long before you are just Jevan’s dad.’ ”

As Jevan prepared for high school, the Sneads decided it was time for a drastic change — one that would give their children more opportunities and help Jevan’s budding football career.

They had visited Jevan’s older sister, Jennah, who was attending Tarleton State University in Stephenville, and decided they liked the town, which had about 15,000 people at the time. The local high school was known for its football program.

“My dad said, ‘I just don’t know if he can cut it at a school as big as Stephenville,’ ” Jevan’s sister, Jennah Snead Walker, said. “The coaches looked at my dad and said, ‘He can cut it anywhere.’ ”

Jevan Snead and his family moved to Stephenville his freshman year of high school when he joined the Stephenville High School Yellow Jackets. He became a standout and was heavily recruited for colleges nationally. [Jay Janner/AMERICAN-STATESMAN]

The family left Eden and moved 120 miles northeast, and Jevan joined the Stephenville High Yellow Jackets.

“We saw this tall, blond kid, kind of skinny, and we were like, ‘Who is this kid?’ ” Kenyon recalled. “He picks up the ball, and he chunks it 50 yards easy as a freshman, and we were like, ‘I think we can be friends with this guy.’ ”

Over the next four years, Jevan was a typical high school student and kid brother to a sister five years older. The boy who had taunted her with pranks as a child now turned to her for opinions on his clothes or hairstyle, mastering the clean-cut preppy look he carried for years to come. Brother and sister joked that he wouldn’t know how to get dressed without her.

But on the field, Jevan was all about football.

Stephenville’s coach at the time was Chad Morris, who went on to be the head coach at Lake Travis High School, Southern Methodist University and the University of Arkansas and is now offensive coordinator and quarterbacks coach at Auburn University.

“He and Jevan just clicked,” Walker said. “He was a second dad to Jevan.”

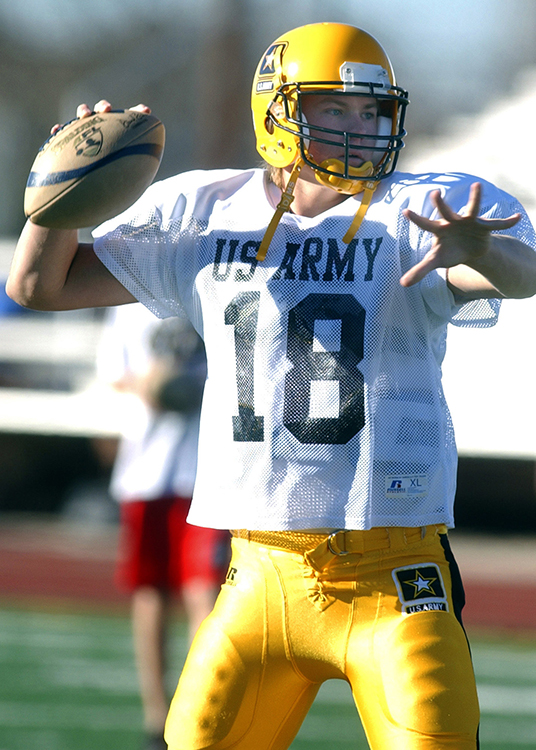

Over the next four years, accolades poured in. Jevan was named to the 2006 Parade All-America team. That year, he also was selected for the U.S. Army All-American Bowl. By his junior year, college offers filled the family’s mailbox. The Sneads still have those letters, piled neatly in Nike shoeboxes.

Jevan Snead practices for the 2006 U.S. Army All-American Bowl during his senior year at Stephenville High School. [Edward A. Ornelas/SAN ANTONIO EXPRESS-NEWS]

Texas quarterback Jevan Snead makes a run for the endzone against Sam Houston State in 2006. [Brian K. Diggs/AMERICAN-STATESMAN]

Ole Miss Rebels quarterback Jevan Snead rolls out to pass against the LSU Tigers in 2009. [Don McPeak/USA TODAY SPORTS]

Snead chose UT after graduating from high school in 2006. He believed famed quarterback Vince Young would be with the team for at least another year, giving him time to train and position himself to replace him. Instead, Young joined the NFL, and the starting job went to Colt McCoy, who had already been with the Longhorns.

Snead was then offered the quarterback position at Ole Miss. He visited and fell in love with the Oxford campus before enrolling in January 2007.

“They were needing a quarterback, and Jevan was needing a place to call home and feel like home,” his sister said. “As soon as he stepped foot on campus and the town, he called and said, ‘Y’all aren’t going to believe this place. The campus is beautiful, and they’ve got so much tradition.’ ”

Over the next three years, Snead flourished. His photo appeared on the cover of the Aug. 17, 2009, issue of Sports Illustrated with the headline: “The Rebels have the firepower to shake up the BCS.” Copies bearing Snead’s autograph are still for sale on Amazon for $400.

You could see his eyes roll into the back of his head, and he was out for what seemed like forever to us.

His time at Ole Miss culminated with the Cotton Bowl, where he completed 13 of 23 passes for 168 yards with three interceptions. On an interception return in the 13th minute of the second quarter, an Oklahoma State player struck him as Jevan closed in for a tackle.

The powerful crash vaulted Snead’s helmet into the air. He landed flat on his back. TV cameras showed him rolling over and later walking off the field and talking to coaches on the sideline.

His family remembers watching from the stands, terrified.

“You could see his eyes roll into the back of his head, and he was out for what seemed like forever to us,” Walker said.

Snead brushed it off and returned for the fourth quarter of his final college game.

But inside his skull, his family believes, the Cotton Bowl crash, compounded by a career dotted with traumas, unleashed a neurological reaction that turned the promising football star into an emotionally fragile young man who felt overwhelmed as his abused brain began to give out on him.

Jevan Snead lies on the field after a brain-jarring hit against Oklahoma State in the 2010 Cotton Bowl. [Tim Heitman/US PRESSWIRE]

Head injuries

In recent years, head injuries to football players have become a conversation with increasing urgency among sports and medical experts.

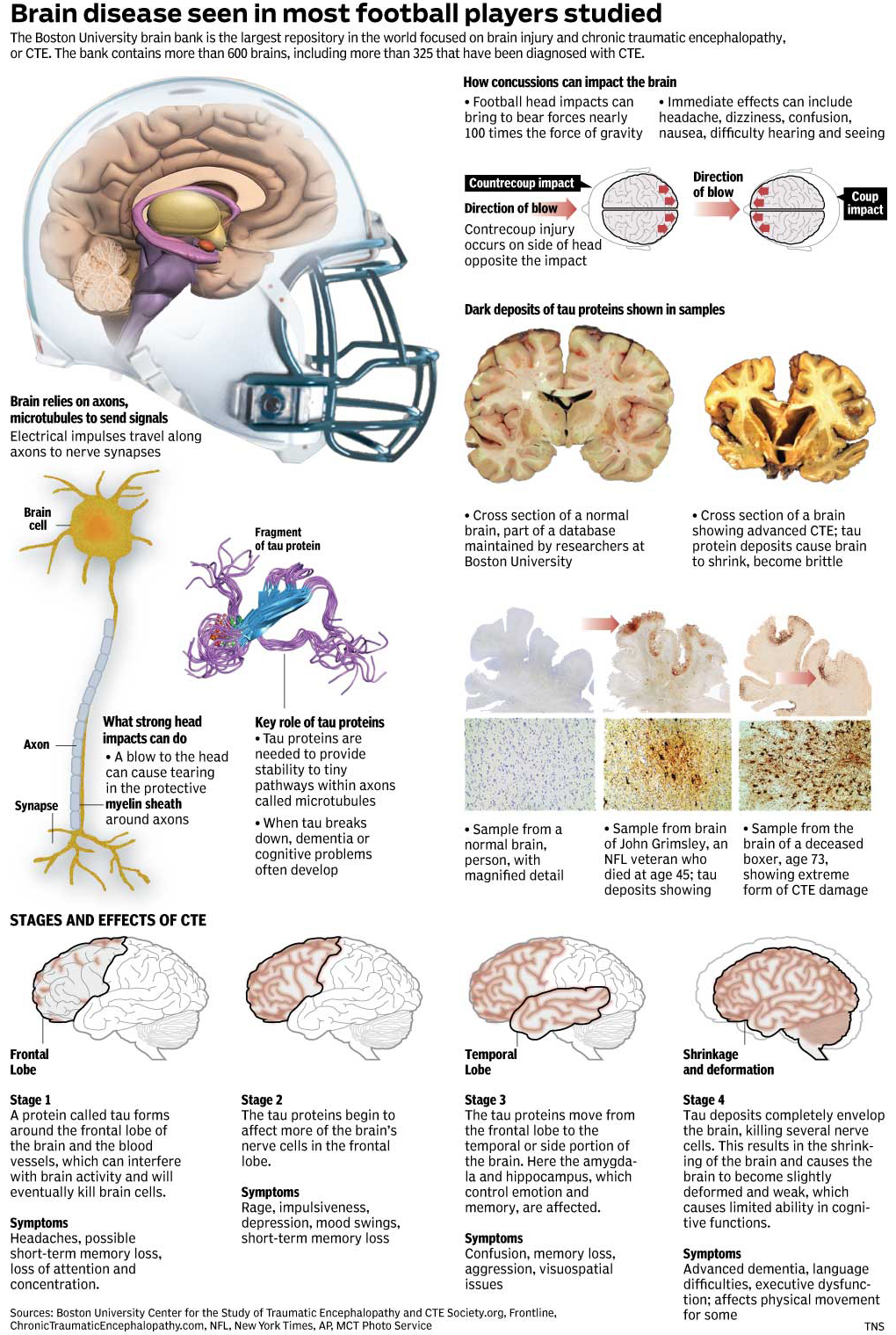

Chronic traumatic encephalopathy, which can only be diagnosed after a person’s death, is generally found in people with a history of repeated brain trauma, including athletes.

“We’ve seen CTE with boxers, football players and people who have had a history of recurrent head injuries, concussions or even subconcussions, where people may have hits to the head but no symptoms associated with it,” said Dr. John Bertelson, an Austin neurologist.

Repeated trauma triggers the buildup of a protein called tau, which can lead to abnormal brain functions months, years or decades later.

The disease is associated with symptoms such as memory loss, impaired judgment, impulse control problems, aggression, depression and suicidal tendencies — many effects that Snead’s family and friends said he showed.

It eventually leads to progressive dementia, according to researchers at Boston University’s Chronic Traumatic Encephalopathy Center who are working to more fully understand genetic risk factors, the age at which a person is at risk and other risk factors. Scientists hope to ultimately develop a treatment.

The issue of CTE has received increased national attention in the past 15 years, beginning with the publication of the first evidence of the condition in a U.S. football player: former Pittsburgh Steeler Mike Webster, whose life after football was plagued with turmoil that published reports say included bouts of homelessness, financial problems and long periods of reclusiveness. He was 50 when he died of a heart attack in 2002.

Since then, the Boston University center has received more than 600 donated brains, mostly from football players. More than 325 of the brains have been diagnosed with CTE.

Revelations about the condition have also led to lawsuits, including one settled last year in Dallas that was brought by the widow of defensive lineman Greg Ploetz, who played at Texas from 1968 to 1971. He died in 2015, and scientists ruled he had extensive brain damage. The lawsuit against the NCAA said he suffered from memory loss, communication issues and confusion. Terms of the settlement have not been made public.

The issue has prompted some states, including Massachusetts, to consider banning tackle football for children in grades seven and under.

Texas has taken steps in recent years to curtail head injuries to players, including the passage of a 2011 law that required school districts to create concussion oversight teams that must include at least one doctor and to establish “return to play” protocols that include an evaluation of a student athlete by a doctor after a possible concussion. The law also required the University Interscholastic League and the Texas Department of State Health Services to create required training courses for coaches and athletic trainers about the dangers of CTE.

Ole Miss quarterback Jevan Snead hits the turf hard enough for his helmet to come loose against Wake Forest in 2008. [Bob Donnan/US PRESSWIRE]

State Rep. Four Price, an Amarillo Republican, said he authored the 2011 law after reading articles about concussions among high school athletes and wondered whether the state was doing enough to protect its youths. The father of four also had two sons who played football.

“There is such a rich tradition of athletics and sports competitions in the state of Texas,” he said. “There isn’t anything I wanted to do to dial that back, but we wanted to promote that by making it safe and improving the health of students who participate.”

Jamey Harrison, deputy director of the University Interscholastic League, which governs Texas high school athletics, said the organization has taken multiple steps to curtail the chances of a student receiving head trauma, including limiting the amount of time a player can participate in full contact practice. Officials also recently began efforts to develop a database of athletes who receive concussions so that they can better answer questions such as the activities that are most likely to result in brain trauma.

“The emotional part of me wonders, ‘What are we doing? Would I let my own child play football? I think a lot of pediatricians don’t let their children play football.”

“All of this information is really about keeping kids safe,” he said. “That is the goal.”

Other organizations, such as the Texas Medical Association, also have become involved to help raise awareness, launching a webpage that has information for physicians, athletes and parents about the dangers of concussions and producing an educational video to help athletes and coaches learn about the effects of multiple concussions.

Dr. Maria Monge, who chairs the association’s committee on child and adolescent health, said many doctors are eager for more data that conclusively links certain activities with CTE. But she said she is hesitant to endorse sports such as football for children and youths.

“The emotional part of me wonders, ‘What are we doing? Would I let my own child play football?’ ” said Monge, an Austin pediatrician. “I think a lot of pediatricians don’t let their children play football.”

From left to right: Jayse, Jane, Jaylon and Jennah poses on Friday, Jan. 24, 2020 at Stephenville City Park as they remember Jevan Snead, a former UT and Ole Miss quarterback who died by suicide in September. [Ricardo B. Brazziell/AMERICAN-STATESMAN]

A spiral after football

After finishing that epic 2010 season and earning an Ole Miss marketing degree, Jevan pressed forward with football, expecting to step into a successful, lucrative NFL career.

He entered the 2010 NFL draft but was passed by. He signed with the Tampa Bay Buccaneers in April but was released in July. After the team’s starting quarterback broke his finger, Jevan signed with the Buccaneers a second time, but he was cut again months later after the injured quarterback returned. In January 2011, he signed to play with the Tampa Bay Storm of the Arena Football League, but he was released before the season after the coach who had recruited him was fired.

Jevan was bedeviled by disappointment that his football career ended so unceremoniously. He was tormented by the notion that he had failed his coaches and the community that had believed in him.

“He would get a little blue in the fall, when football came around. I think he missed it,” Jennah Snead Walker said. “The ‘what ifs’ would creep back in.”

He worked multiple jobs, including in real estate, land development and medical sales, as he tried to make a life in which football wasn’t the driving force.

His listlessness was a perhaps understandable symptom of long-pursued dreams dashed. But Jevan’s friends and family noticed behavior that was more deeply troubling, an increasing level of forgetfulness uncharacteristic of a man in his early 30s.

“He would get a little blue in the fall, when football came around. I think he missed it,” older sister Jennah Snead Walker said of her brother. “The ‘what ifs’ would creep back in.” [Ricardo B. Brazziell/AMERICAN-STATESMAN]

Jevan Snead and his brother, Jayse, in one of Snead’s post-football trips to the University of Mississippi, where he was a star quarterback. Snead loved Ole Miss, including tailgating in the Grove, and often talked about how much the university felt like home. [Contributed]

His sister says he couldn’t remember things she mentioned about their childhood such as funny memories from holiday meals.

During a golfing weekend with a friend, he forgot the course from one day to the next.

He so doubted his memory that he constantly made reminder notes to himself about anything from work assignments to dinner plans, then took pictures of them on his phone so he had them at all times.

His moods became erratic, and he was often impulsive.

“It was, ‘I’m tired of this job; let’s go in a different direction,’ ” Jennah Snead Walker said.

And he wrestled with periodic depression.

“The highs were really high, and the lows were really low, and it would change just like that,” she said. “It would turn on a dime.”

Jevan met with another disappointment after he moved to California to pursue a relationship last year. He returned to Austin after the breakup last spring and worked as a consultant for WeWork, a startup that provides office space for remote workers.

He began making new friends, rekindling old relationships and casually dating.

Whitney Wilson met Jevan casually a couple of years ago, and she said the two immediately had chemistry.

“It was an easy friendship to be in,” she said. “He had such good energy and made you feel comfortable.”

Jevan Snead lived in Newport Beach, Calif., for about a year and returned several times after returning to Texas to play golf. His parents believe this photo was taken in September 2019, a couple of weeks before his death. [Contributed]

Jevan Snead in Newport Beach, Calif., with a friend’s dog in the summer of 2018. [Contributed]

When he returned to Austin, the two began spending time together, often with a larger group of friends at Ranch 616, one of their favorite spots downtown.

Wilson says she knew last fall that Snead was struggling with depression and anxiety over everything from his football past to his professional future. He was consumed with self-doubt about almost everything, including his appearance.

“Here was a person who is tall, attractive,” Wilson said. “He had already achieved a considerable amount of success at such an early age. But for Jevan, it seemed to be just the opposite. I could tell him he was perfect, and he would just hear whatever he wanted to hear.”

On Saturday, Sept. 21, Jevan was supposed to pick up a friend from California at the airport in Austin. But when that friend and others, including Wilson, didn’t hear from him all day, they knew something was wrong.

They eventually called the police. When officers forced their way into his South Austin apartment, they found Jevan in his bathroom with a tan belt around his neck.

On Sunday morning Sept. 22, as Kenyon was leaving for church, Jevan’s parents called him with the horrible news.

“That’s the only time I’ve ever been mad at God and asked him, ‘Why didn’t you show up?’ ” Kenyon said. “‘Why didn’t you show him what you’ve shown me when I’ve been down?’ When he died, a little piece of me died.”

In keeping with his wishes, Jevan’s family donated his brain to the Boston center for research, hoping to learn something that could help the next generation of young football players. The family also has begun raising money to buy helmets for school districts that otherwise can’t afford top-of-the-line safety gear.

Six months after his friend’s death, Kenyon often scrolls through pictures of Snead on his phone. He’s dug up older ones, too, from their glory days on the field at Stephenville High School.

Kenyon often thinks back to the conversation he had with Snead on his back patio last spring, when the depth of his memory loss took full focus.

He is still haunted by his friend’s response when he mentioned one of the most pivotal moments of Jevan’s career, one that he has replayed over and over again on YouTube as he grieves.

He also thinks about the night Jevan took his life. Kenyon had been coaching in a football game and considered calling him around 11 p.m., as he was trying to come down from the night’s adrenaline rush.

He figured Jevan was out with friends, so instead he texted a video. Kenyon had used his cellphone to record a video that had been shown on the school’s Jumbotron introducing the football coaching staff earlier that night.

“Getting big time,” Kenyon joked as he typed what became his last text to his friend. “You know what this is all about.”

“Hahaha,” Jevan responded. “I love you.”

Jevan Snead gestures in triumph to the Mississippi fans after the Rebels’ 47-34 win over Texas Tech in the 2009 Cotton Bowl. [Stew Milne/US PRESSWIRE]