the macdonald Family murders

Fort Bragg murder Case intrigues 50 years later

Former Army doctor Jeffrey MacDonald, serving three life sentences for the deaths of his wife and daughters, has always maintained his innocence.

The call for help came shortly after 3:30 on a Tuesday morning. The man who dialed the operator relayed a desperate situation.

He said his name was Capt. MacDonald, there had been stabbings, and he needed a doctor, military police and an ambulance to come to his home at 544 Castle Drive on Fort Bragg.

The man dropped the phone, but the line stayed open. The operator called the military police at Fort Bragg, and she connected the man when he picked up the phone a few moments later.

Soon, MPs were on their way. It was Feb. 17, 1970, some 50 years ago.

• • •

When military police arrived, they found Jeffrey MacDonald lying next to his wife on a blood-covered floor in the master bedroom. The 26-year-old Army doctor had a puncture wound to his chest, but he was alive.

Colette MacDonald, 26, lay dead. So did 5-year-old Kimberley and 2-year-old Kristen in their bedrooms nearby.

Who did this?

The question terrified the people of Fayetteville and Fort Bragg on that miserable February morning. And it has captivated the public for five decades.

MacDonald, 76, is serving three consecutive life sentences in federal prison for the murders. He says he was wrongly convicted while the police let the real killers, often described as a group of four “drug-crazed hippies,” get away.

MacDonald has been in and out of courtrooms since the summer of 1970 to assert his claim he is innocent.

Sometimes he won; ultimately he lost.

The facts for and against MacDonald have been hashed out since 1970 in news accounts, at least five books, on television and, in modern times, on websites and in true-crime podcasts. This account of the MacDonald murders and their aftermath is drawn from court documents, newspaper archives, the true-crime books “Fatal Vision,” “Fatal Justice” and “A Wilderness of Error,” and the memories of people who lived here.

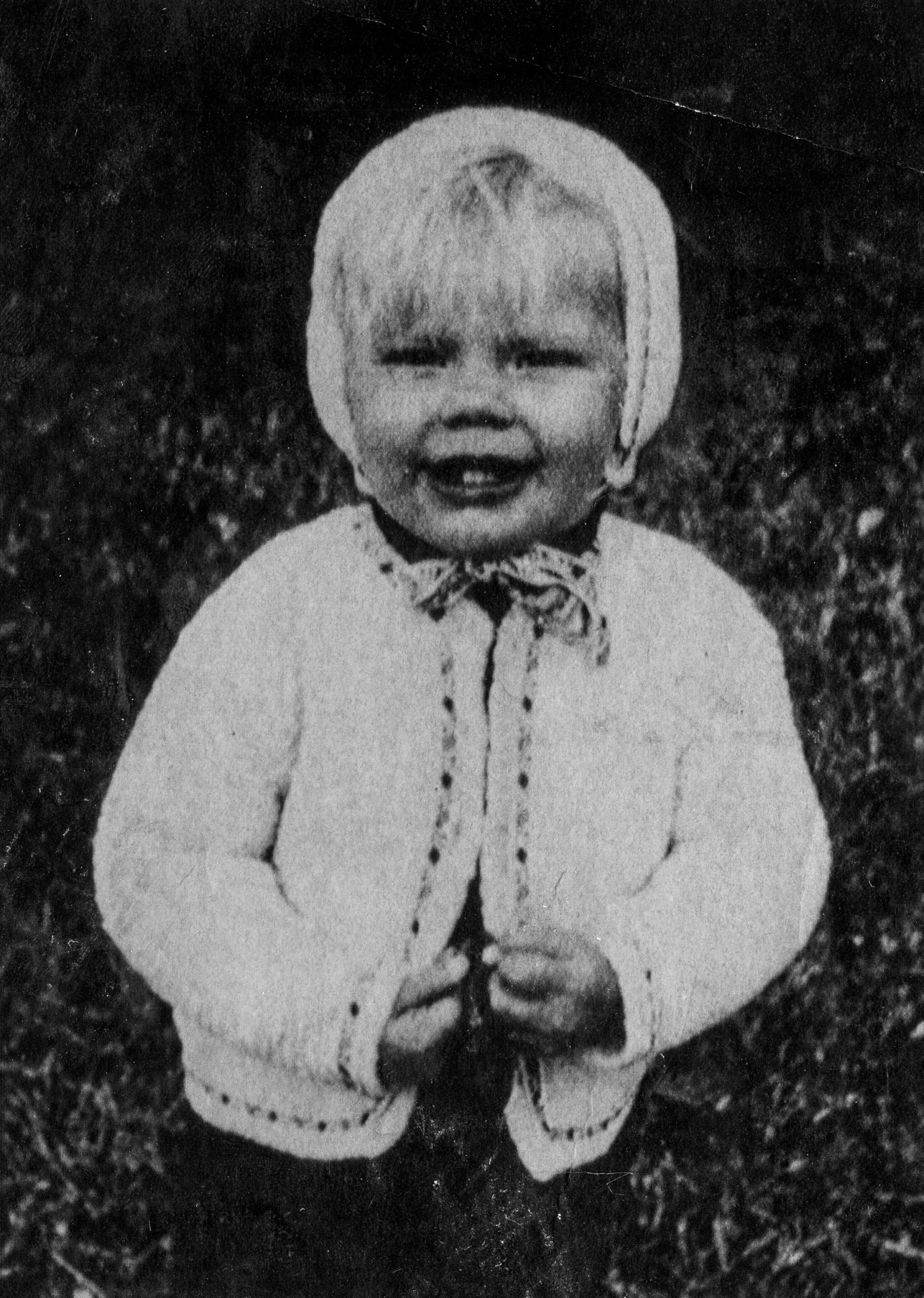

Kimberley MacDonald. [AP photo]

Colette MacDonald [UPI photo]

Kristen MacDonald [AP photo]

THE CRIME SCENE

The MacDonalds lived in Corregidor Courts, a housing area for officers and noncommissioned officers. The residence was one of four units in a brick building. There were two one-floor apartments on the ends, and two two-story apartments in the middle. The MacDonalds lived in an end unit.

“It was a nasty, rainy, cold day,” said news reporter Jeff Thompson of Up & Coming Weekly. In 1970, Thompson was the news director at WFNC radio and one of the first reporters to arrive at the MacDonald home.

One of the MPs later testified that while he was en route to Castle Drive, he saw a woman standing at an intersection about a half mile away. She was wearing a dark raincoat and a wide-brimmed hat. He thought it unusual that a woman would be out in the rain shortly before 4 a.m. This would later become a significant point.

All seemed quiet when police arrived. The books say eight to 12 MPs were there.

The front door was locked, and the MPs were hesitant to break in. One found a back door to a utility room open. He went inside and found carnage.

The utility room led to the master bedroom where Colette MacDonald, four months pregnant, lay on her back on the floor. Blood soaked her pajamas and the carpet beneath her head from dozens of stab wounds to her neck and chest and blows from a bat or club that fractured her skull.

Jeffrey MacDonald lay face down, his head on Colette’s shoulder or chest. He was wearing only his pajama bottoms. His pajama top was on Colette’s body.

MacDonald had a stab wound that partly deflated a lung.

Someone had smeared the word “pig” in blood on the headboard of the bed.

MacDonald stirred and told the MPs to check on his children.

Down the hall from the master bedroom, 5-year-old Kimberley and 2-year-old Kristen were in their beds. Kimberley had been beaten in the head and stabbed. Kristen was stabbed to death.

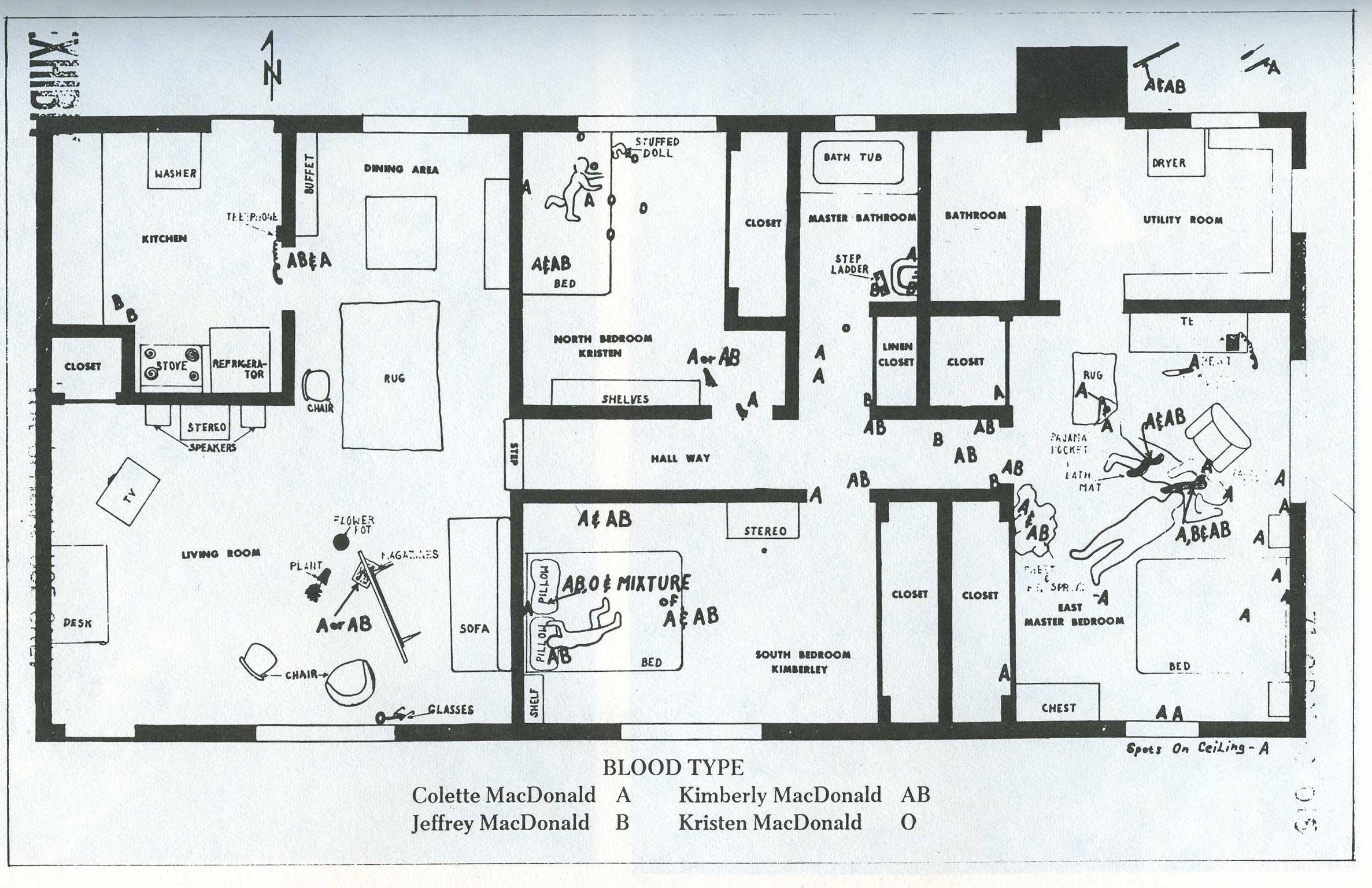

The hall ended at the living room. A crime-scene sketch depicts the coffee table on its side on top of a stack of magazines. A flowerpot was nearby, with the plant and its root ball lying on the floor next to it. There was a pair of eyeglasses on the floor by a wall with a speck of blood on them, say books about the case.

Special Forces soldiers carry the bodies of Colette MacDonald and her two children, Kimberley, 5, and Kristen, 2, into the JFK Chapel on Fort Bragg in 1970. [Bill Shaw/The Fayetteville Observer]

MACDONALD’S STORY

MacDonald appeared partly conscious when the police found him, according to the books and court records. In the house and in later interviews, he gave his description of what happened:

• MacDonald had been asleep on the living room couch and woke to the sound of screaming. He thought it was Colette or possibly Kimberley.

• When MacDonald awoke, he saw two white men, a black man and a white woman in the living room with him. He said the black man wore an Army jacket with sergeant stripes on the shoulder, and the woman had blond hair, a floppy hat and brown boots.

• The woman appeared to be holding a candle. MacDonald recounted that the woman was saying, “Kill the pigs. Acid’s groovy,” and, “Acid is groovy. Kill the pigs.”

• MacDonald said he fought the intruders. One hit him in the head with a bat or club, which he said he grabbed. He said he was stabbed with an ice pick. He said he kept fighting until he fell unconscious.

• MacDonald said he awoke on the hallway floor then searched the house and found the bodies. He said he pulled a knife from Colette’s chest.

FBI floor plan of the MacDonald residence as presented to the jury and included in “Fatal Justice,” a book about the murders and trial by Joe McGinness. [Fatal Justice]

Investigators found a knife in the bedroom. They also found a blood-stained club, an ice pick and another knife in the backyard.

At the time, Fort Bragg was an open post, with no security gates or checkpoints to stop anyone from entering and roaming as they pleased.

The initial report of the killings was the top story in The Fayetteville Observer that afternoon: “Officer’s Wife, Children Found Slain At Ft. Bragg.” Longtime crime reporter Pat Reese wrote that Colette and the children were “apparently murder victims of a ‘ritualistic’ hippie cult.”

The killings and the parallels with the Manson murders six months earlier put people on edge, said Cumberland County Commissioner Jimmy Keefe, who was 8 at the time and whose father was a Special Forces soldier.

“There was a lot of fear that families weren’t safe,” Keefe said.

A longtime Fayetteville resident, who didn’t want her name in the news, recalled the sounds of her neighbors nailing their windows shut.

“I think the first night, I went to bed with a hammer under my pillow,” she said. “And then I started thinking, ‘Hey – if anybody breaks in, he could have killed me with the hammer.’ So I put it back in the toolbox.”

Many people bought firearms, said Thompson, the WFNC news director.

“Everyone went gun crazy. Given the recent Manson murders and then this, the pawnshops were all selling out of rifles and handguns,” he said.

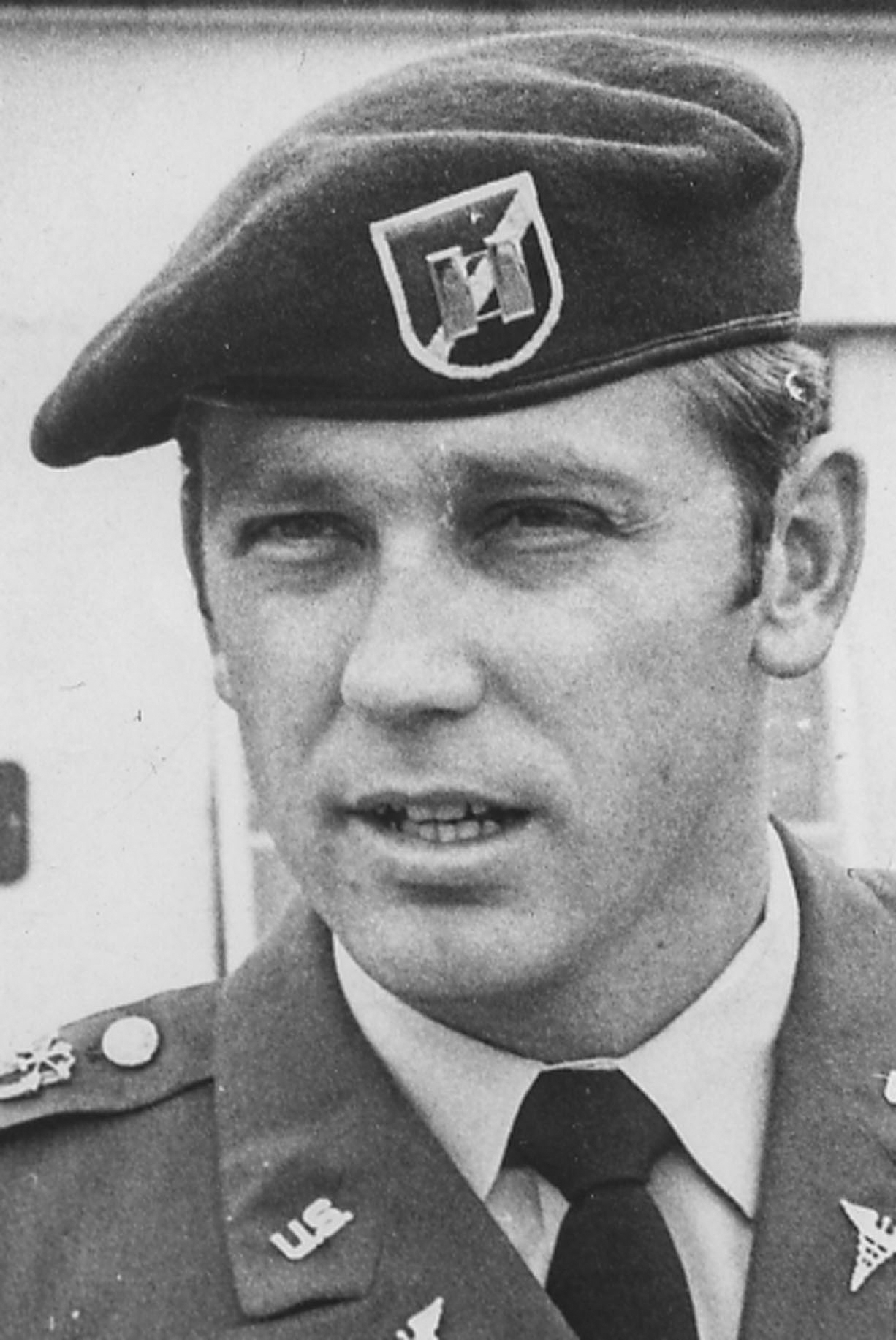

Capt. Jeffrey MacDonald in October 1970. [File/The Fayetteville Observer]

THE INVESTIGATION

Former Hope Mills Police Chief John Hodges, who died last summer, was an Army police investigator in 1970.

“He was actually the first CID agent on the scene that night,” said his son, Hope Mills Fire Chief Chuck Hodges. “CID” is a common term for the Army’s Criminal Investigation Command.

Chuck Hodges said his father and the other investigators had doubts about MacDonald’s story of a home invasion from the beginning.

“I think they pretty much saw — at least the CID investigators — pretty much saw right away that some stuff wasn’t adding up,” Hodges said.

They thought home invaders would have attacked MacDonald, the biggest threat, before attacking his wife and children, he said. The investigators also noted MacDonald’s injuries compared to those of Colette, Kimberley and Kristen.

“The wound that he had was nothing compared to what they got,” Hodges said. “So that kind of raised some eyebrows.”

The crime-scene and autopsy photos of Colette and the children are gruesome and bloody.

The reports say:

• Colette was stabbed 16 times with a knife and 21 times with an ice pick, and she was hit in the head with a club at least six times. Both of her arms were broken, as though she had been defending herself.

• Kimberley was hit twice in the head and stabbed with a knife eight to 10 times in her neck.

• Kristen was stabbed 17 times with a knife and had 15 puncture wounds in her chest. Her hands were cut in what appeared to be defensive wounds.

Accounts differ as to the overall severity of MacDonald’s injuries, but there is no question they were light compared to what his wife and children suffered. His most serious wound was an ice-pick stab to his chest that partly deflated his lung.

“Fatal Justice,” a book that says MacDonald was wrongly convicted, says MacDonald had at least three bruises on his head, a bruise on his shoulder and upper left arm, and a bruise on his left forearm that could be considered a defensive wound.

In addition to the stabbing that punctured MacDonald’s lung, “Fatal Justice” lists a knife wound that went through MacDonald’s bicep, puncture wounds to his arm, two cuts to his hand, four or five ice-pick wounds to his chest, two knife wounds to his abdomen and several ice-pick wounds to his abdomen.

While the community fretted about murderous hippies, the investigators saw anomalies in the living room where MacDonald said he fought off four people.

“When one considered that it was an area in which a life-and-death struggle had taken place between a Green Beret officer and four intruders who had obviously been in some sort of murderous frenzy and at least some of whom had been armed, there seemed remarkably few signs of disorder,” wrote author Joe McGinness in 1983’s “Fatal Vision,” the first book published about the MacDonald case. McGinness portrayed MacDonald as guilty.

MacDonald had been a physician for a Green Beret unit at Fort Bragg. He took care of the health of the Special Forces soldiers, but he was not a Special Forces soldier. Special Forces soldiers receive intense training in combat and survival skills and in how to work with insurgencies in foreign countries.

The CID investigators concluded that MacDonald killed his family and then intentionally injured himself and staged the living room to support his claim of a home invasion.

The Army charged MacDonald with the homicides of his wife and daughters on May 1, 1970.

MUDDIED WATERS

From the beginning, the MPs and emergency workers fouled up, casting doubt on the quality and findings of their investigation.

There’s no question that the investigators were thorough. The books describe them meticulously collecting fiber samples, bits of blood-stained surgical gloves, and other physical clues. But they also made critical mistakes in the house and during laboratory work.

Some of these mistakes, according to the authors of the books about the case, are:

• An ambulance driver stole Jeffrey MacDonald’s wallet from the home and also set the fallen flowerpot upright. The upright flowerpot added to the impression that MacDonald staged the crime scene.

• Examiners failed to collect fingerprints from the children’s bodies. Some fingerprints from the crime scene were accidentally destroyed, and so were some bloody footprints.

Again it was raining, the whole area is muddy as hell . MPs were traipsing in and out of the house rather casually. Law enforcement back in the day isn’t what it is now.

• A piece of skin that was found under Colette’s fingernail, possibly from her scratching her attacker, disappeared after it was collected.

• MPs and investigators had picked up and read a blood-smeared copy of Esquire magazine in the living room. It was covered with their fingerprints. The magazine’s cover story was about the Manson murders.

• When the MPs first arrived, one of Colette’s breasts was exposed. But the crime-scene photos show her upper body covered with a towel — a signal that evidence was moved, writes author Errol Morris in 2012’s “A Wilderness of Error.” Morris says MacDonald is innocent.

• They let newsmen, neighbors and others roam the front yard and backyard before the evidence was processed. They let the garbage collectors empty the MacDonalds’ trash cans before they could be examined for evidence.

Thompson said he saw a news photographer walk to the side of the house and take pictures through the windows.

“Again it was raining, the whole area is muddy as hell,” Thompson said. “MPs were traipsing in and out of the house rather casually. Law enforcement back in the day isn’t what it is now.”

The crime-scene errors cast doubt on the prosecution’s case that summer when the Army conducted an Article 32 investigation, a trial-like hearing used in the military justice system to determine whether to court-martial a service member accused of a crime.

The MacDonald case provided a harsh lesson for the military about preservation of crime scenes, said Kelvin Culbreth, a local Cumulus Media radio executive who grew up in Fayetteville. In 1984, Culbreth joined the Army and went to military police school in Alabama.

One of the most important jobs of an MP is to preserve a crime scene to protect the evidence for the investigators, Culbreth said. His instructors had a training room modeled after the MacDonald home, he said, and they used the MacDonald case as a scenario and example of what not to do.

“There was just so many things, so many things that contaminated that crime scene,” he said.

At the time, Culbreth happened to be reading “Fatal Vision.”“It was all really interesting to me at that point,” he said.

Jeffrey MacDonald gets into a car on Fort Bragg in 1970. [Bill Shaw/The Fayetteville Observer]

ARTICLE 32

Jeffrey MacDonald’s Article 32 investigation ran from July 6 to Sept. 11.

The military often describes an Article 32 investigation as the military justice system’s version of a grand jury proceeding in civilian courts. But there are key differences: The defendant can have his lawyer present evidence, and the presiding officer, not a jury, makes a recommendation on whether to prosecute the defendant.

It became clear quickly that the law enforcement investigators did a poor job of protecting and preserving the crime scene. It also emerged that a hair found in Colette MacDonald’s hand did not come from Jeffrey MacDonald and candle wax found in the house did not match the candles that the MacDonalds owned.

The investigators contended that there was no way that the MacDonalds’ living room coffee table would have ended up on its side during a struggle. They said they repeatedly knocked it over to try to recreate the fight conditions that MacDonald described and it always landed upside down on the floor. This was evidence, they said, that MacDonald staged the scene.

The presiding officer decided to see for himself. He went to the MacDonald residence and kicked the table. It landed on its side.

Further, it was revealed that in February, 17-year-old Helena Stoeckley of Fayetteville, a drug-using police informant in the local hippie community, had made comments about the MacDonald case to the Fayetteville police officer she worked with. Her statements were vague and imprecise, but they potentially implicated her as being present during the murders.

But she said she was high that night and couldn’t be sure.

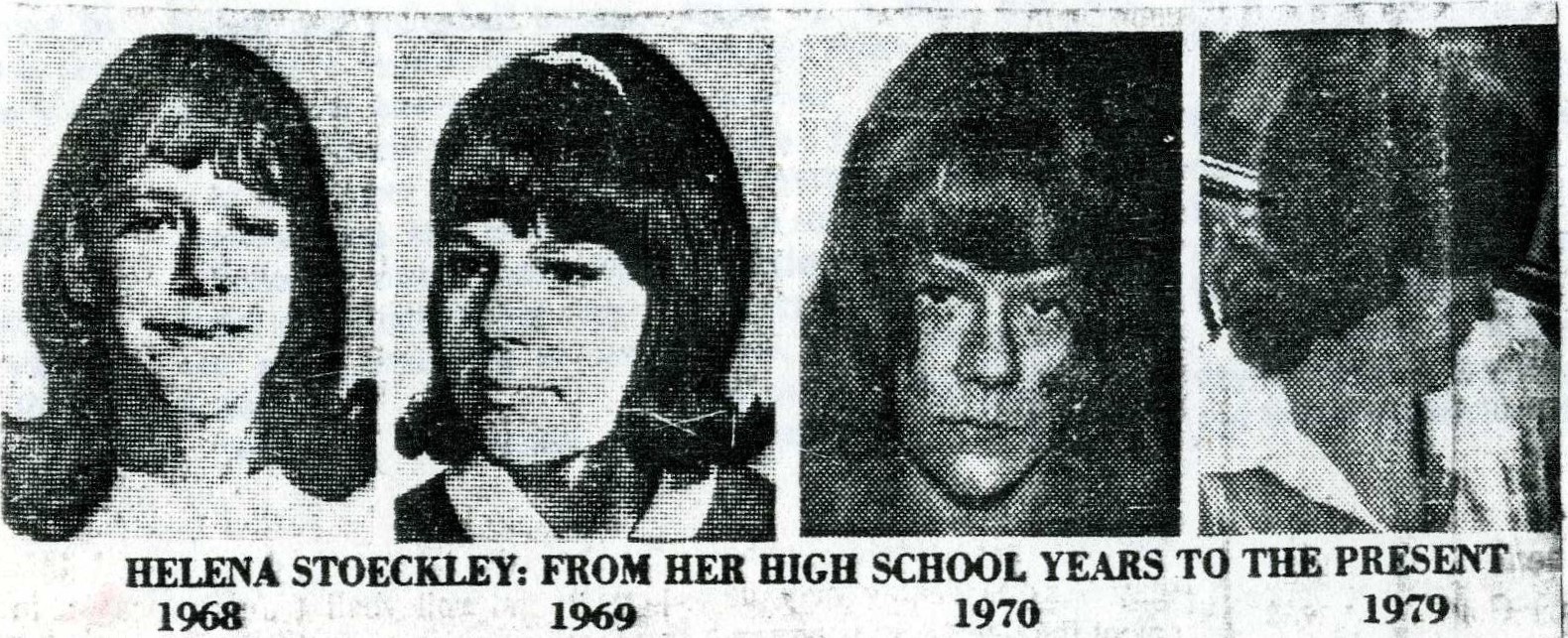

Photos of Helena Stoeckley from high school to 1979. [The Fayetteville Observer files]

Stoeckley was known to have worn a blond wig, boots and a large floppy hat.

Could Stoeckley have been the woman who one of the MPs saw standing in the rain a few blocks from the MacDonald home as he was en route to the crime scene? Google Maps says it takes 11 minutes to walk from that corner to 544 Castle Drive.

In October 1970, the Army dropped all charges against MacDonald. The investigating officer in the Article 32 hearing, Col. Warren V. Rock, said civilian authorities should investigate Stoeckley.

MacDonald left the military in December 1970, and in 1971 he moved to California to restart his life and his medical career.

By June 1979, wrote McGinniss in “Fatal Vision,” MacDonald was the director of emergency medicine at a hospital. His condo had parking out front for his sports car and was on the water in the back to accommodate his 34-foot yacht.

MacDonald would be moving into a prison cell less than three months later.

CASE REOPENED

In early 1971, Helena Stoeckley was again giving police contradictory statements about the MacDonald case. Sometimes she said she thought she was there. Sometimes she said she couldn’t remember that night. She also said she had nightmares.

In April 1971, she took polygraph tests.

An examiner concluded that Stoeckley believed she had been present during the murders and knew who killed Colette MacDonald and the children. However, the examiner said no conclusion could be made as to the accuracy of Stoeckley’s statements because of Stoeckley’s state of mind and her excessive drug use in February 1970, wrote author Morris in “A Wilderness of Error.”

An investigator took a hair sample from Stoeckley and got her fingerprints, “Fatal Vision” author McGinniss wrote. These did not match any that were found at the crime scene.

MacDonald remained a suspect as the investigation continued.

Colette MacDonald’s family originally believed that Jeffrey was innocent. But over time, this changed and they became convinced that he was guilty. Colette’s stepfather, Freddy Kassab, relentlessly lobbied authorities to keep the investigation alive.

Finally, in August 1974, a federal grand jury convened to evaluate the case. Jeffrey MacDonald was among the people interviewed before it. The jury indicted him in January 1975.

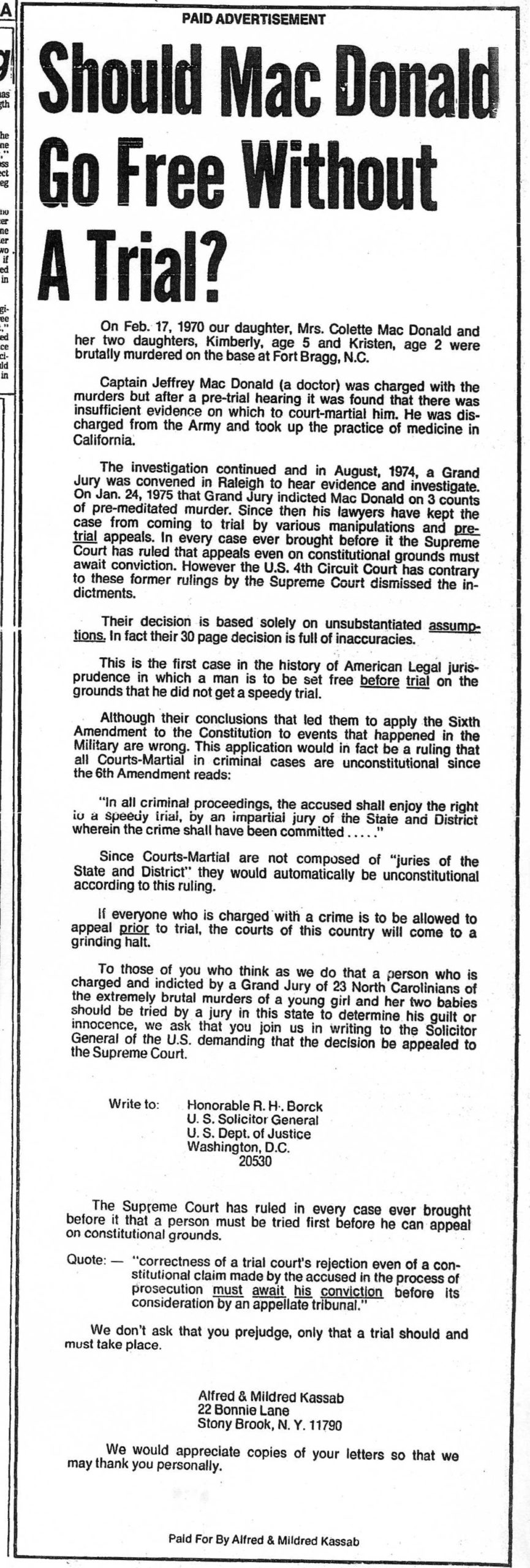

This ad, paid for by Colette MacDonald’s stepfather Alfred Kassab, ran in The Fayetteville Observer on June 6, 1976. [The Fayetteville Observer files]

CONVICTED

The trial ran from July 19 to Aug. 29, 1979.

In “Fatal Vision,” some jurors told McGinniss they were unpersuaded by the prosecution’s case until they listened to a recording of a law enforcement interview with MacDonald from April 1970.

“He just didn’t sound like a man telling the truth,” said one.

That was just one of the many pieces of evidence.

It appeared that someone wearing surgical gloves had written “pig” in blood on the headboard.

An analyst from the FBI gave extensive testimony about the blood patterns, holes and rips in the bedding and in MacDonald’s pajamas. The analyst concluded that someone had stabbed Colette in the chest with an ice pick through Jeffrey’s pajama top.

He just didn’t sound like a man telling the truth

In this era before DNA evidence, investigators used the different blood types of the MacDonalds and their children, and where their blood was found throughout the apartment, to convince the jurors that MacDonald had moved from room to room to commit these killings.

Over the objections of MacDonald’s lawyers, the prosecutors had articles from Esquire magazine about the Manson murder case in California read to the jury. This was the issue found with blood smeared on it in the MacDonalds’ living room.

The prosecutors pointed out similarities between the Manson case as described in the magazine and the MacDonald murders. For example, one of the killers had written “pig” on a door in the blood of Sharon Tate.

The jury deliberated less than a day. It found MacDonald guilty of second-degree murder in the deaths of Colette and Kimberley and first-degree murder in the death of Kristen.

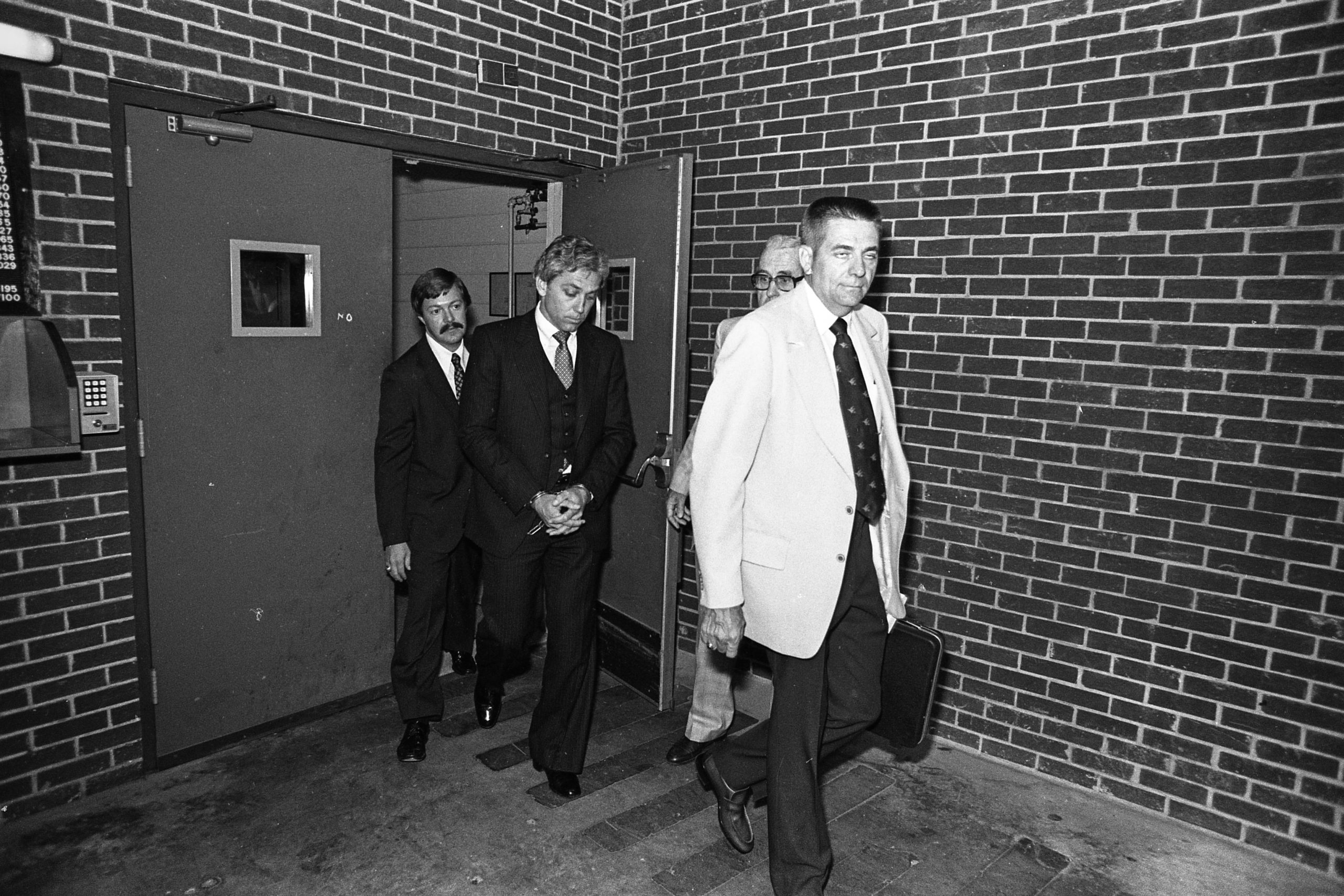

Jeffrey MacDonald, second from left, is led out in handcuffs at the federal courthouse in Raleigh on Aug. 29, 1979, after being found guilty of murdering his family in 1970. [Cramer Gallimore/The Fayetteville Observer]

HOMETOWN HAUNT

As much as the MacDonald case captivated the country, with its publicity in national magazines, major newspapers and on television, it also became part of the culture of Fayetteville.

Chuck Hodges, the son of former CID investigator John Hodges, said when he was growing up, visiting relatives asked about the case and the house at 544 Castle Drive.

“We would go and take family to see the ‘murder house,’” Hodges said. “We would get out and walk up to the front porch and walk around the back.”

Kelvin Culbreth, the radio executive, said he was a pizza driver in the summers when he was home from college. Sometimes he passed the house while making deliveries. “Ten, 12 years later, it was still boarded up,” he said.

The home had been kept sealed while the case was pending. But the street was accessible to the public as Fort Bragg was years from installing the security gates that now guard its entrances.

A longtime resident said that when she was a teenager, she and her friends used to sit in front of the house to see how long it took before they became scared.

Some to this day say MacDonald is innocent and was wrongly convicted. Others have no doubt he is guilty.

Fort Bragg MPs stand guard as workers prepare to leave the site of the MacDonald murders at 544 Castle Drive on Fort Bragg on June 7, 1984. The apartment was being cleaned out and repaired. [Cramer Gallimore/The Fayetteville Observer]

The house remained a crime scene for nine-and-a-half years and remained boarded up for 14 years in all, The Fayetteville Observer reported in 2000. The U.S. Justice Department released it back to the military in 1983 and by 1987 it had been renovated into a duplex. Families began living in it again.

In February 2000, 30 years after the murders, a 31-year-old sergeant lived at 544 Castle Drive with his wife and children. People still stopped on the street to take pictures of the home, the sergeant said, and some knocked on the door and asked to look inside.

The building was torn down in March 2008 to make way for an 11,000-square-foot community recreation center and swimming pool.

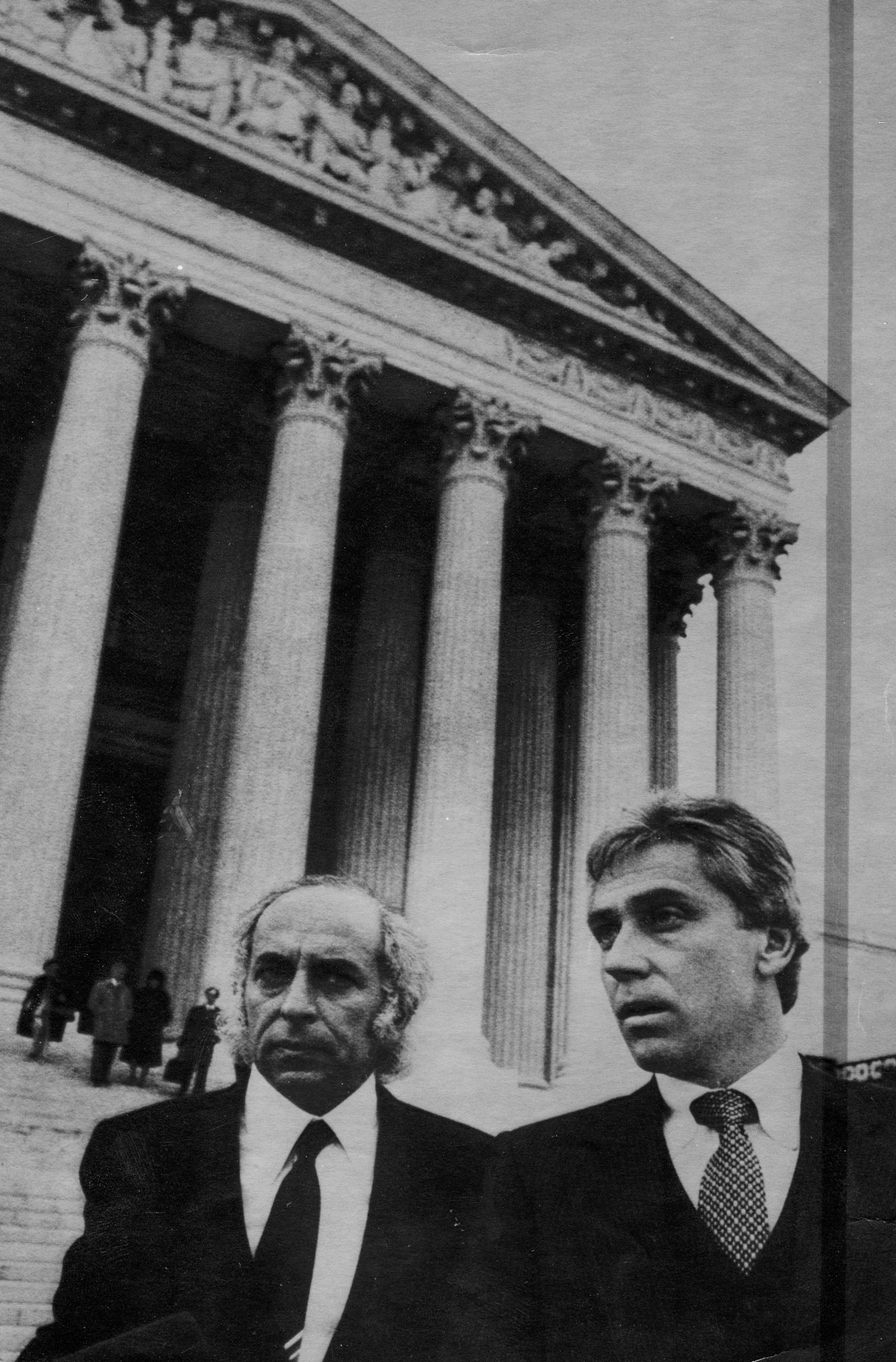

Dr. Jeffrey MacDonald, right, and his attorney Bernie Segal leave the Supreme Court building in December 1981 after a hearing before the high court on a government motion seeking to reinstate MacDonald’s murder conviction. The conviction was overturned by a federal appeals court, which said that MacDonald did not receive a speedy trial. [AP photo]

COURT FIGHT CONTINUES

MacDonald appealed his conviction.

He had a respite in 1980 when the 4th Circuit Court of Appeals ruled that his right to a speedy trial had been violated and he was released from prison that August.

But the Supreme Court reversed that ruling in March 1982, and MacDonald went back behind bars.

Helena Stoeckley died in 1983.

When DNA testing emerged as a new forensic tool, MacDonald sought testing of the evidence to prove someone else killed his family. In 2006, a strand of hair from under 2-year-old Kristen’s fingernail could not be matched to anyone.

In 2012, MacDonald finally got a new hearing. Prison officials brought him to the federal courthouse in Wilmington to be present while his lawyers made his case to U.S. District Judge James C. Fox.

They said MacDonald deserved a new trial for several reasons, including:

• A deceased U.S. marshal was reported to have said he drove Helena Stoeckley from South Carolina to MacDonald’s trial in 1979 and she admitted being in the MacDonald home during the murders. However, the marshal allegedly said, Stoeckley was coerced by a prosecutor to keep that to herself, lest she be charged with murder.

• DNA testing from three hairs found at the crime scene could not be matched to anyone, lending credence to MacDonald’s home-invasion claim.

The prosecutors countered that one of the hairs (it was the one from Kristen’s fingernail) may have been an incident of crime-scene contamination, and the other two could have been in the home long before the homicides.

They said the dead marshal’s claims couldn’t be trusted because travel records and testimony from other marshals showed he had gotten his facts wrong about the trip. The marshal died in 2008.

Fox ruled against MacDonald in 2014. MacDonald appealed but lost at the 4th Circuit Court of Appeals in 2018, and the Supreme Court declined this past October to take up his case.

For the moment, MacDonald has no more pending court actions, said lawyer Hart Miles of Raleigh. Miles represented MacDonald in his most-recent efforts to prove he was wrongly convicted.“Jeff has not given up and continues to explore avenues to get back in court but I don’t know when anything might be filed,” Miles said in an email Friday evening.

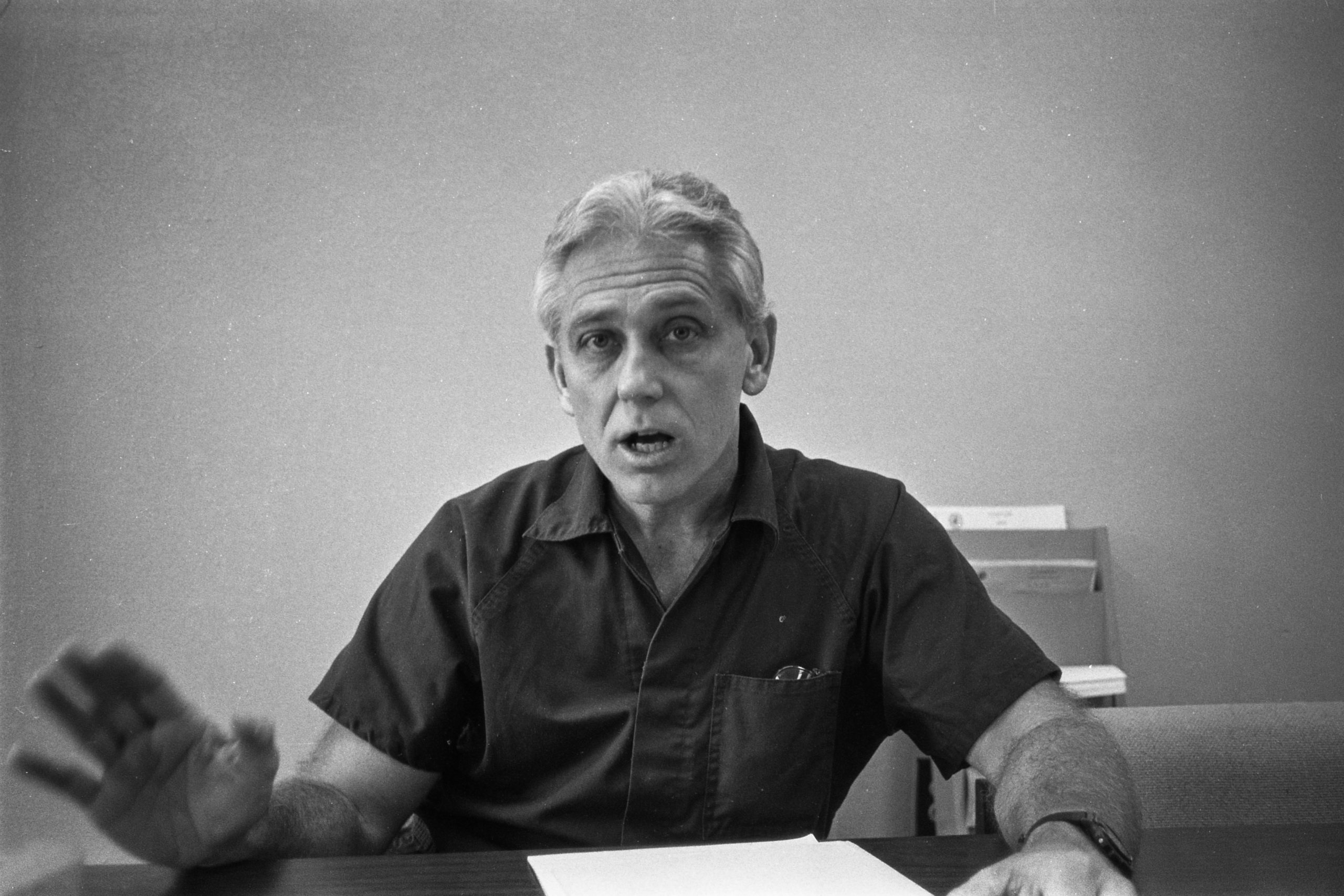

Jeffrey MacDonald speaks to a reporter at the Federal Correctional Institution at Terminal Island, Calif., on Feb. 14, 1990. MacDonald is locked up there for the murder of his wife and two children. [File/The Fayetteville Observer]

PAROLE?

For now, MacDonald’s next chance for freedom is parole.

He first became eligible in 1991, but he didn’t have a parole hearing until May 2005, the U.S. Department of Justice said.

Parole was denied then, and the U.S. Parole Commission said MacDonald must wait 15 years for reconsideration. His next opportunity is in May. A Justice Department spokesman said MacDonald has not applied for a hearing.

Will he?

MacDonald isn’t saying. This month he declined an interview request with The Fayetteville Observer and at least one other media outlet, according to the U.S. Bureau of Prisons.

His wife, Kathryn MacDonald, did not respond to requests for comment.

LEGACY

The case brought national media scrutiny to Fayetteville and Fort Bragg on and off for years.

Thompson, the former radio reporter, said the MacDonald homicides were the first of a series of cases over the next decades in which a military person was charged with a high-profile murder in the Fayetteville and Fort Bragg area.

“It certainly gave our community some notoriety,” said former Fayetteville Mayor Marshall B. Pitts Jr.

Even years later, Pitts said, “people you run into across the state or parts of the country, they would be well familiar with the Jeffrey MacDonald case. It definitely had a resonating kind of an effect from a high-profile standpoint.”

Out-of-towners rarely ask about the case nowadays, said John Meroski, president of the Fayetteville Area Convention and Visitors Bureau. It tends to happen if a television movie about it has played or if there is court activity, he said. It doesn’t necessarily scare people away.

People you run into across the state or parts of the country, they would be well familiar with the Jeffrey MacDonald case. It definitely had a resonating kind of an effect from a high-profile standpoint.

“I think an older generation who might have remembered it and passed the story along to others could contribute to some narrative,” he said. “However, since it’s so long ago, and because of today’s world of social media and short attention spans, it really doesn’t — it doesn’t really affect our industry.”

Talk about the case has faded as people who were alive at the time of the murders and the trial have died, said Pitts.

“It’s not as prevalent as it once was, of course, as time goes on,” he said. “But still, unfortunately, there are remnants there as far as our community goes.”

Despite the age of the MacDonald case, the publicity and national fascination continue.

The FX television network is preparing to broadcast a five-part documentary series about it, a spokeswoman said. The series is based on “A Wilderness of Error.”

The premiere date has not been announced.

Staff writer Paul Woolverton can be reached at pwoolverton@fayobserver.com or 910-486-3512.