The Wilds has grown into nationally known animal conservation center

CUMBERLAND, Ohio — When Dave Clawson first arrived at The Wilds nearly 30 years ago, he saw promise in the foliage taking root in the 10,000 acres of near-nothingness.

There were no animals roaming the pastures. There was no running water, phone line or electricity.

Just a visitors' building, a half-finished animal barn and a few fences stood on the land that was once strip-mined for coal in Cumberland, about 75 miles east of Columbus.

But thanks to restoration efforts, grass covered it again. Tiny trees, their growth stunted by the damaged soil, dotted rolling hills filled with roughly 150 lakes that had been carved into the terrain.

To Clawson, it was perfect.

He envisioned herds of rare animals someday roaming the wide open spaces, replicating their natural grassland habitats.

So in 1990, Clawson took a chance and left a job he loved, caring for the Columbus Zoo and Aquarium's rhinos, elephants and other animals under the leadership of zoo Director Jack Hanna. At that time, The Wilds was a nonprofit group operated in partnership with several Ohio zoos, including Columbus. Clawson became its first animal management specialist, a title he still holds.

"I'm kind of a dreamer, and once you've seen The Wilds, you understand it's something totally different," Clawson, now 55, said. "It just seemed like the thing to do."

Today, under the management of the Columbus Zoo and Aquarium, The Wilds has grown into one of North America's largest conservation centers, with more than 500 animals representing 28 species, including some, such as Père David's deer, which are only alive in captivity. Breeding programs have successfully reintroduced rare animals into the wild. Ecologists gauge efforts to restore the area to its condition before strip-mining, which is positively affecting the area's native species, such as insects, birds and bats.

The site in rural Ohio even inspires Hanna, who has traveled the world.

"Every time I visit, I just still can't get over what they've done," Hanna said. "If I didn't have a cabin in Montana, I promise you, it would be at The Wilds. I'm a hyper person, but when I go there, I relax and become somebody else."

'Garden of Eden'

Hanna still recalls the first time he saw the site that was to become The Wilds.

Shortly after Hanna became the Columbus Zoo's director in 1978, Robert Teater, director of the Ohio Department of Natural Resources at the time, offered Hanna a helicopter ride. What he saw shocked him.

"When I looked down, I almost fell out of the helicopter," Hanna said. "I said, 'This is the Garden of Eden. They're going to give this to us?'"

Eventually, Hanna realized he had actually seen the site before.

With fellow Muskingum University students — including Suzi, who would eventually become his wife — Hanna rode bicycles by it in the 1960s to observe the world's largest coal excavator, the Big Muskie, tearing through barren earth that resembled the surface of the moon.

A lot had changed since then.

Planning for what would eventually become The Wilds began in the 1970s. Officials envisioned it as a partnership involving state agencies, zoos across the state and private partners. The plan was to use the space to breed and study rare zoo animals in large pastures resembling their natural habitats.

In 1984, the effort was formally incorporated as a nonprofit called the International Center for the Preservation of Wild Animals Inc. and received more than 9,100 acres donated from the Central Ohio Coal Company, an American Electric Power Company subsidiary.

The conservation center, eventually dubbed The Wilds, didn't officially open for another 10 years.

IN THE SERIES:

Jack Hanna's antics on TV put Columbus Zoo in national spotlight

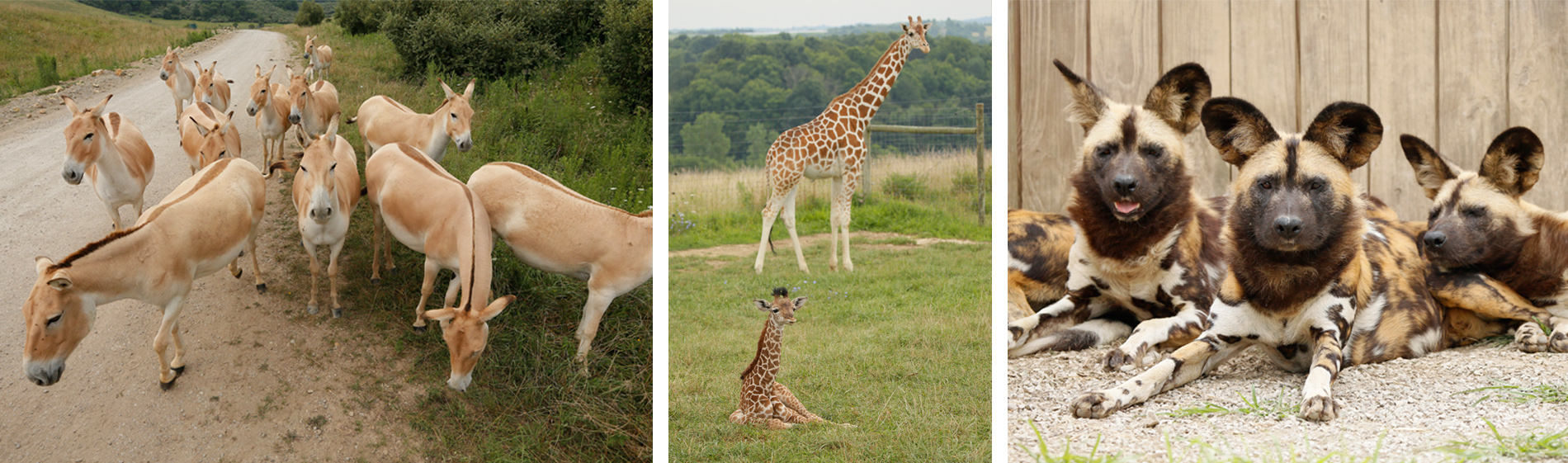

Its first animals, Przewalski's wild horses, an endangered species native to Asia, arrived in 1992. Two years later, safari tours started. That same year, Hanna became director emeritus of the Columbus Zoo, to focus more on his TV career and public appearances instead of the zoo's day-to-day operations.

Early on, the center faced some challenges, especially financial trouble.

Eventually, the four involved Ohio zoos and now-defunct Kings Island Wild Animal Habitat dropped out — leaving Columbus, which purchased part of the nonprofit and became its manager in the early 2000s to salvage it.

In recent years, new entertainment offerings beyond safari tours, including zip-lining, lodging, horseback riding, fishing and educational camps, have helped increase the center's revenue and the amount of time that visitors stay.

It's an approach happening at conservation centers across the country because most are facing similar challenges, said Katy Palfrey, CEO of Conservation Centers for Species Survival, a nonprofit group founded in 2005 to help centers work together and thrive. The Wilds was a founding member of the group.

Such centers require a lot of land and subsequently aren't usually close to urban areas. They're also not yet as well-known as traditional zoos, and typically don't "toot their own horns," so luring guests can be a challenge, Palfrey said.

By recognizing the value of entertainment, The Wilds can continue to provide cutting-edge education, conservation and research, Palfrey said.

"It has to go hand-in-hand, to some extent, to get people engaged," she said.

Like what you're reading?

Stories that inspire. Coverage that informs. Investigations that affect change. This is real news just when it's needed most. Subscribe today. Subscribe

Herd mentality

Once guests arrive at The Wilds, there's nothing more exciting than teaching them about the conservation work happening in the safari park's pastures as well as behind-the-scenes, said Jan Ramer, its vice president.

"We do our piece in Ohio, but we also have a global impact," she said.

Ramer took on the top job at The Wilds in 2017 after two years as its director of conservation medicine and staff veterinarian. Before that, she'd spent several years in Rwanda working for Gorilla Doctors, a team of veterinarians who provide lifesaving care to endangered wild gorillas.

The Wilds is as close to the real thing as you can get, she said.

In a herd, captive animals behave more naturally, Ramer said.

The extra space means breeding programs are less restricted. She said some of The Wilds' most impressive breeding successes involve hoofed animals that, at first glance, might not look too out of the ordinary.

IN THE SERIES:

Columbus Zoo's animal ambassadors bring need for conservation efforts to life

The center, for example, was the first institution to successfully use artificial insemination to breed Persian onagers, an endangered species of wild ass that has only 600 to 700 wild animals left living in two protected areas in Iran. Animals such as the scimitar-horned oryx, an antelope extinct in the wild since the 1970s, have been successfully reintroduced into their habitats in Chad, in part thanks to the work at The Wilds. The Père David's deer is another rare species at The Wilds that is currently extinct in its habitat of China.

But a naturalistic environment can come with trade-offs, too.

To provide animals with extensive veterinary care, they must be sedated and temporarily separated from their herds and social hierarchies, which can be difficult and risky. For example, a herd might not accept an animal if it is separated for too long, Ramer said.

"You have to be more creative and careful with your thinking," she said.

Exotic animals aren't the only ones being studied at The Wilds, either.

The center coordinates many programs aimed at conserving native species, including the Eastern hellbender salamander and the American burying beetle, both federally endangered. And restoration ecologists are studying how well native prairie grasses reclaim former mining sites; the plants are now being reintroduced into other damaged areas in southern Ohio.

Students also regularly take advantage of learning opportunities at The Wilds because of its proximity to Muskingum University, Hanna's alma mater, said its president Susan Hasseler.

Colton Wilson, 20, a junior biology major, spent this summer continuing ongoing research of rare birds that are attracted to The Wilds' unique grasslands — including some so elusive that people drive across the country to see them. The studies found that shrubs popping up in the grasses were driving the bird populations away, so staff members are removing the unwanted plants.

Wilson, of Indian Lake in Logan County, couldn't believe such a dynamic research hub goes unnoticed by so many people in Ohio. He hadn't visited until he started his internship, he said.

"It's massive, and unlike anything I've ever really seen before," Wilson said.

Smart growth

As those working at The Wilds look to the future, they hope to continue spreading their message, increasing their visitors and conserving wildlife. Hanna, though not involved much in the day-to-day operations of the center, continues to be one of its biggest champions, Ramer said.

This year, The Wilds debuted seven Straker Lake cabins and a partnership with the Mighty Oaks Warrior Programs, a nonprofit group that hosts retreats there during summer months for veterans with post-traumatic stress disorder.

The Wilds' annual attendance has grown to about 120,000 people.

A breeding program that reared the only fifth-generation southern white rhinos outside of Africa received the Edward H. Bean Award's top honors from the national Association of Zoos and Aquariums last year. The association is a nonprofit group of more than 230 accredited members in the United States and abroad, including the Columbus Zoo and The Wilds.

As The Wilds continues to grow, Clawson said he expects it to retain the same quaint charm it had when he first saw it in 1990.

"There was a lot of vision and speculation on what was happening out here at that time, both on-site and in the animal community," Clawson recalled. "There were some bumps along the road, but I'm not sure anyone knew it would be what it is today."