Files detail investigation into Megan Rondini case

By Stephanie Taylor

The night of July 1, 2015, started as a typical one for both Megan Rondini and T.J. Bunn Jr.

Rondini had finished exams at the University of Alabama and was spending a few days in Tuscaloosa before heading home for the summer to Austin, Texas.

She and a few sorority sisters met at Innisfree Irish Pub on University Boulevard to play trivia and share pitchers of beer.

Bunn finished up work at his family’s business, ST Bunn Construction, that Wednesday evening and walked across the street to Innisfree, where he spent most of the night sitting at the corner of the bar having drinks and talking to friends.

What happened after they left the bar separately that night has become the basis of rape and corruption allegations that have captured the attention of people far beyond Tuscaloosa, eliciting strong emotions, opinions and outrage.

A young woman is dead, leaving behind a mourning family looking to hold someone responsible for her death, while seeking change within the system they believe failed their daughter.

A man has been cast by some as a dangerous predator — not convicted by a judge or jury, but by public opinion in an ongoing “trial by social media.”

Rondini was 20 when she reported to police that Bunn, 34 at the time, raped her at his home that night. The Tuscaloosa County Metro Homicide Unit conducted an investigation, and after consulting with prosecutors decided there wasn’t enough evidence to make an arrest. Bunn has denied the allegation, saying the sex was consensual.

That September, the homicide unit turned the case over to the Tuscaloosa County District Attorney’s Office, a common procedure in investigations that don’t result in an immediate arrest. Prosecutors then have the option of presenting the evidence to a grand jury for a final determination, which they did in this case, in February 2016. The grand jury did not issue an indictment.

Rondini moved back to Texas six weeks into the following fall semester, and would never learn the outcome of the grand jury deliberations. She took her life a few days before the panel met, hanging herself with a hammock cord in the bathroom of her Dallas apartment.

Her parents filed a wrongful death suit in early July this year against Bunn, the University of Alabama, UA President Stuart Bell, Tuscaloosa County Sheriff Ron Abernathy and the two lead investigators who worked the case. The suit claims their actions — or inaction — caused Rondini to suffer post-traumatic stress disorder, depression and anxiety, ultimately leading to her suicide.

The actions of those institutions and individuals will be reviewed by a federal judge and possibly a jury as the lawsuit progresses.

Ten days before the suit was filed, BuzzFeed News published a story online that had been read by 2.3 million people as of Tuesday. The story suggested Rondini was drugged, raped and later failed by medical professionals, law enforcement and UA counseling staff because Bunn comes from a wealthy family.

The BuzzFeed story included clips from videos included in the investigative file, which the court had ordered the Sheriff’s Office to release to the Rondinis’ attorneys. Bunn’s attorneys obtained the same file after the story was published.

The Tuscaloosa News sought the investigative file, not all of which would ordinarily be public record, in order to provide the public with as much information as possible about the case, rather than rely on what might have been selectively released or published elsewhere.

“A lot of information about this matter has appeared online and on social media, much of it unsubstantiated and unsourced,” Tuscaloosa News executive editor Michael James said when the paper requested the files. “We believe that’s irresponsible. Considering the gravity of the accusations and insinuations that have arisen with regard to institutions the public should have faith and confidence in, we believe it would be in the public interest for the court to order the release of the records.”

At a court hearing on Sept. 11, Tuscaloosa County Circuit Court Judge Brad Almond granted The News’ request.

According to the Sheriff’s Office, the file contains all investigative materials related to the case, including audio and video recordings of interviews with Bunn and Rondini. There are recorded interviews with Bunn’s friend, who spent the night at Bunn’s house, and Rondini’s friend who picked her up there after 2 a.m. Also included in the file are photos and video of the house, Rondini’s written statement and her text messages and phone photos dating back to 2013.

The News has made all of the material available online, with the exception of text messages and photos that aren’t relevant to the case. Some names, phone numbers and personal information have been redacted. An interview with Rondini’s friend that was provided as a video has been presented as an audio file to protect her privacy.

Click to read the written investigation file.

What follows is a chronological account of the night of July 1 and the subsequent investigation, based on information in the investigative file.

7 p.m. – 11:47 p.m.: July 1, 2015

Bunn arrived alone at Innisfree Irish Pub at 7:25 p.m. On surveillance video from Innisfree, he can be seen talking on his phone on the outside porch for about two minutes before going inside.

(The time stamps on Innisfree surveillance videos were not altered to reflect daylight saving time.)

Rondini and five friends arrive at Innisfree at 8:19 p.m., walking past staff members who didn’t check identification. They can be seen entering from the left at the 8:30 mark in the following video.

Four other friends joined them later for trivia. Several hours of surveillance video doesn’t appear to show Rondini and Bunn having any contact while inside the bar.

“I recognized him because we met on Thanksgiving,” Rondini told Investigator Adam Jones in an interview the following day. The interview began at 11:30 a.m. at the Tuscaloosa County Sheriff’s Office and lasted more than three hours.

“He probably didn’t remember who I was, but every time I go out, I see him there,” Rondini said. “He’s always there. As soon as we walked in I saw him, and he was sitting at the bar. We didn’t talk at all, he didn’t even acknowledge that I was there, I didn’t acknowledge that he was there. He didn’t talk to any of my friends.”

Click here to see all of the Innisfree videos.

Rondini can be seen in the video below, sitting under the left arch under the television at the 9:57 mark in the video, at 11:11 p.m. Bunn and his friend Jason Barksdale leave at 11:35 p.m., walking from the left of the screen to the exit in the far right corner. Rondini leaves at 11:36 p.m.

Rondini told investigators she drank around five or six cups of beer she poured herself from shared pitchers. In text messages exchanged with her father the following morning, after she had been examined at DCH Regional Medical Center, he asked whether the nurse had taken a blood sample “to document if he drugged you.” She replied, “I don’t think I was drugged bc my drink never left my friends but I can try to go back.”

Bunn and Barksdale left the bar at 11:35 p.m. Rondini left alone at 11:36 p.m., walking east on University Boulevard. Bunn’s white Mercedes can be seen on surveillance photo as it exits the ST Bunn parking lot at 11:39 p.m. and travels east on University Boulevard.

Bunn and Barksdale can be seen leaving at the 35:33 mark in the following video, with Rondini exiting at 36:46. His Mercedes appears on University Boulevard at 38:47.

Bunn told investigators in an interview that took place at the Sheriff’s Office July 6, that he saw Rondini walking along University Boulevard, about a block from Innisfree, before he stopped to offer her a ride.

“I’ve seen her, I knew her face,” he told Investigator Josh Hastings.

“After we left, I noticed that she was walking by herself down the road,” Bunn said. “I pulled over and asked if she needed a ride home. She gets in the car, as soon as she gets in the car, she calls me by name.”

“I don’t really remember actually leaving Innisfree,” Rondini said. “I feel I would have left with my friends that were going to drive us home. But I do remember being in the car with him on the road, in the back seat.”

Rondini said she remembered passing Denny Chimes on University Boulevard.

“It wasn’t like hostile, we were just all in the car together,” she said.

She recalled that Bunn asked what she was studying. She replied that she liked animals and wanted to be a veterinarian, and he told her about the room in his home with mounts of animals he’s killed on hunting trips. Rondini said that Bunn drove straight to his home in Cottondale, without making any stops.

“Originally, I thought he was just going to drive me home, and then I kind of realize that’s not what was…” she said, trailing off. “After being in the car awhile, I realized that’s not where we were going.

“He was drunk and he was driving and it was kind of concerning me,” she said. “I was kind of watching him drive the whole time because it was scaring me.”

But surveillance photos and cell phone data show that the group did go to Rondini’s apartment at Houndstooth Condominiums on 15th Street for 15 minutes.

“I did exactly what I told her, what I asked her to do, I drove her straight home to her apartment,” Bunn said.

11:47 p.m. – 12:15 a.m.

Surveillance footage from inside the apartment complex shows the group arriving at 11:47 p.m., and leaving at 12:02 a.m. Rondini is leading the way each time, followed by Bunn and then Barksdale.

They arrive at the 21:33 mark in the following video:

“She invited us to come in, we go upstairs, she fixes us a drink. I don’t touch anything, she made it,” Bunn said during the July 6 interview at the Sheriff’s Office.

Rondini told officers she didn’t remember going home. With her permission, they used her phone data to look at location history and texts that confirmed she was there for 15 minutes.

“I don’t remember being there,” she said during the interview with investigators on July 2. “There’s a gap. I don’t remember leaving, and I don’t remember getting in the car.”

Rondini voluntarily gave investigators her phone so they could download her location history. The investigators never requested information from Bunn’s phone.

When asked why Bunn’s phone wasn’t examined, Abernathy, in an email, said:

“Ms. Rondini voluntarily provided her cell telephone to law enforcement for downloading to provide investigators evidence supplementary to that provided by her oral statement. After she advised investigators she no longer wanted the investigation to go forward, this documentary evidence was retained, but no other cell telephone evidence was offered to investigators. Documentary evidence voluntarily provided by Ms. Rondini was beneficial to the investigation because it provided supplemented evidence not offered by her oral statement.”

Investigator Jones accompanied Rondini to her apartment that day, where he took photos and recorded their discussion. A photo shows one cup in the sink and a glass on the coffee table. A bottle of Everclear grain alcohol and a bottle of Canadian Mist whiskey were by the sink. She said she didn’t recall making drinks, but acknowledged there may have been a smaller amount in the bottles than the previous day.

“When we decided to leave, she chose to want to go with us and we got to my house and we pretty much, everybody went straight to bed,” Bunn said. “We didn’t fix another drink, we didn’t stay up. We went to bed, and it’s, of course, unfortunately we both decided to have consensual sex.”

The group can be seen leaving her apartment at the 21:09 mark:

Bunn said he drove from Rondini’s apartment with her in the front seat and Barksdale in the back. Video shows them leaving at 12:02 a.m. It’s about seven miles, an approximately 15-minute trip, to Bunn’s home on Cedar Drive in Cottondale.

Rondini told investigators that she didn’t call or text anyone while in Bunn’s car.

According to her phone records, however, she had the following exchange with a friend who, with Rondini, had met Bunn the previous Thanksgiving at Innisfree and who had been at Innisfree with her earlier that night:

12:05 a.m. Megan: Pick me up in the morning

12:06 a.m. Friend: Kk I have class at 10 so early ish

12:08 a.m. Megan: We are going to guck

12:08 a.m. Megan: (emoji with sunglasses)

12:11 a.m. Friend: Do it (money bag emoji)

12:11 a.m. Friend: Wear a condom

12:11 a.m. Friend: Good luck

12:13 a.m. Megan: Eww but I’ll make it real good

12:14 a.m. Friend: Hahah like a tru horseback rider

Click here to read all of Megan Rondini’s texts

She never writes that she is with Bunn, but had sent two Snapchat photos to that friend at 11:44 p.m. before arriving at her apartment. Investigators were unable to recover those photos from the phone.

Then, while at Bunn’s home, Rondini sent three videos to friends at 12:23 a.m., using the Snapchat app, that she later saved to her phone at 7:14 a.m. The videos were taken inside the room where animals are mounted on the wall — including a leopard, lion, elephant and hippopotamus. Rondini can be heard laughing while walking through the room, naming animals, while Bunn and Barksdale are talking in the background.

Two different friends responded at 12:29 a.m. and 12:32 a.m.

“Megan, where the hell are you?” one wrote.

“Where the f— are you?? Aren’t you a vegetarian?!”

There’s no activity on her phone until 1:04 a.m.

12:15 a.m. – 1:04 a.m.

Rondini told Jones that Barksdale was “very drunk” and that Bunn told him to stop when he made remarks about her legs. The three of them then went into the room with the mounted animals, where she filmed the Snapchat videos.

“I was just really trying not to be rude. I thought he just wanted to show me that room that had the animals in it and maybe we would leave, so I didn’t say anything at that time,” Rondini said in the interview. “I said, once we were in there, I said ‘I need to go find my friends and he just kind of ignored me.”

“I was just really trying not to be rude. I thought he just wanted to show me that room that had the animals in it and maybe we would leave, so I didn’t say anything at that time,” Rondini said in the interview. “I said, once we were in there, I said ‘I need to go find my friends and he just kind of ignored me.”

Bunn told Barksdale to go to bed because he was drunk, Rondini said. Barksdale and Rondini both went upstairs, she said, and went into separate bedrooms. Bunn had directed her to his bedroom, where she waited 10 or 15 minutes on a chair while he put his dog away, she said.

There doesn’t appear to be any phone activity during that time, according to the records.

“He made comments like he wanted to have sex, and I really didn’t want to. He walked over to me, started trying to kiss me, and I didn’t really want to. I was just like ‘I need to leave, and he just ignored me, and I thought if I kind of let him do whatever…,” she said. “When we had sex I didn’t even face him at all. I didn’t look at him.”

She said that Bunn removed her shirt.

“I wasn’t really looking at him. I’d already said I’d needed to leave and he wasn’t really responding to that and I just, I kind of just let him do it.”

“When he started to touch me, I was not responsive to him at all,” she said later in the interview. “I honestly felt like if, because he wasn’t going to stop, if I just kind of let him, then I would be able to leave.”

Jones asked whether she ever felt like she was in danger.

“I did not want to be there,” she said. “I don’t feel like I was in danger, like he was going to kill me, you know, but…”

Later during the interview, Jones continued to ask whether she offered any resistance, and how she communicated to Bunn that she didn’t want to have sex.

“I did try to resist him. I said I wanted to leave, when he tried to kiss me I turned away,” she said. “I didn’t want it to happen, and I’m pretty sure I was clear that I didn’t want it to happen.”

“I believe that you’re telling me the truth about everything we’re talking about,” Jones said. “But when we’re talking about a rape…why didn’t you call the police?”

“I thought about it,” she replied. “At first, I wasn’t even going to go to the hospital, and my friends told me that I should go. I didn’t want to make it a big deal.”

Rondini said that she was on her side during the act. During his interview, Bunn said Rondini was on top of him.

Hastings asked Bunn if Rondini at any point ever told him to stop.

“At no point during y’all having sex did she ever say ‘stop’? She was a willing participant the entire time?” Hastings asked.

“Very willing participant,” he said.

Bunn rolled over and fell asleep afterward, Rondini said.

“I got up to leave, I went to the bathroom and I was kind of panicking,” she said. “I was trying to get my shoes on and that’s when I started texting my friends, saying that I need somebody to come get me right now.”

1:04 a.m. – 2:13 a.m.

Rondini said she tried to leave the room through several doors until she found the right one. She said she panicked when she couldn’t get the door unlocked.

She then sent a flurry of text messages to her friends, starting at 1:04 a.m. and ending more than an hour later when two friends arrived. The messages started with “Cb can you come get me right now” followed by “I need help.” At 1:10 a.m., she wrote “I can’t get out of the room help.”

At 1:12 a.m., she sent a photo to her friends of herself in Bunn’s room, in the dark, with a window in the background.

At 1:12 a.m., she sent a photo to her friends of herself in Bunn’s room, in the dark, with a window in the background.

Some friends responded that they were too drunk to drive to Cottondale and told her to remain calm while they tried to contact someone to pick her up.

She told police that she looked around, but couldn’t find her keys. She found a key ring on a shelf in Bunn’s room, but none of the keys worked on the door she was unable to open.

Rondini texted friends at 1:19 a.m., saying she was going to climb out of the bedroom window. Two minutes later, she reported that she had made it to the ground. After exiting the window, she crossed a flat roof and lowered herself to the driveway using a wrought-iron fence. She said she ran to the street and tried to call friends and taxi services.

“Please please please help me,” she wrote in a series of texts between 1:40 a.m. and when her friends arrived shortly after 2 a.m.

“Why will no one help me,” she wrote, followed by messages including “Please please please” and “Please I’m crying.”

She tried to go through the locked front door to check the first-floor animal room for her keys, she said, using keys she had taken from Bunn’s room.

She then stacked a trash can on a cooler to climb back on the roof and re-enter the bedroom to look for her keys again, but she crawled back out through the window when she couldn’t find them.

“I only went back inside because I knew he wouldn’t wake up,” she said during the interview at the Sheriff’s Office the following day.

While inside again, she searched Bunn’s pants pockets looking for another key that might open the front door, she said. She said she took $3 cash, some assorted papers and an old football ticket that were bundled in his wallet before leaving through the window again.

Rondini said she then searched the Mercedes for her keys. She found a Ruger pistol in the center console that she said discharged when she handled it. Police never found where the bullet landed, but found a shell casing in the front seat of the car, as if it had fired while she was sitting in the front seat.

She didn’t mention that she had found the gun until Jones asked if there were any details she had left out, and didn’t say that it had fired until later in the interview.

“I didn’t tell you this earlier, but I remembered when I was sitting down – when I went to go look for my keys in the Mercedes there was a pocket pistol, or whatever, and I just put it in my shorts for myself,” she said.

She kept the gun in her pocket, she said, and later left it in the grass by the roadside, along with the items from Bunn’s wallet, when her friends arrived. She gave the $3 to the cab driver who arrived just before her friends.

Bunn told police when they questioned him the following morning and the next week that he was missing a company gas card and more than $300.

In the recorded video of him speaking with his lawyer before the July 6 interview, Bunn said he had searched his house but never found Rondini’s keys.

“You’ve got reasoning behind why you did what you did,” Jones said before reading Rondini her Miranda rights and questioning her about the gun and missing money from Bunn’s wallet, in case they ended up charging her with firing a gun or theft. She never faced any charges, but prosecutors had planned to present charges to a grand jury before she died.

“I need you to tell me what your reasoning was about why you did these things,” Jones said. “We’ve just got to touch base on everything, that’s just why we’ve got to go over this. Because we’ve got to find out what happened in every aspect.”

“I was not intentionally trying to shoot anything,” she said. “At all.”

“Did you not tell me this thinking you would be in trouble?” Jones asked.

“I honestly forgot about it,” she said. “I knew the gun part, but I forgot about the cash part.”

He asked why she didn’t mention the gun sooner.

“I was just, they just make me really nervous,” she said. “I was not trying to hurt…I didn’t aim it. I just, I should not have touched it.”

She kept the gun in her pocket, she said, and later left it in the grass by the roadside, along with the items from Bunn’s wallet, when her friends arrived. She gave the $3 to the cab driver who arrived just before her friends.

2:13 a.m. – 6 a.m.

Rondini’s friends arrived at Bunn’s house at 2:13 a.m., just as she was getting into the cab she’d called and paid for with the credit card she kept in her phone case.

The two friends who picked her up had been asleep, and hadn’t been at Innisfree that night. They returned to their apartment, where they talked before they drove Rondini about a block to the hospital.

“She was telling me she wasn’t comfortable with what happened,” one friend said during an interview at the Sheriff’s Office.

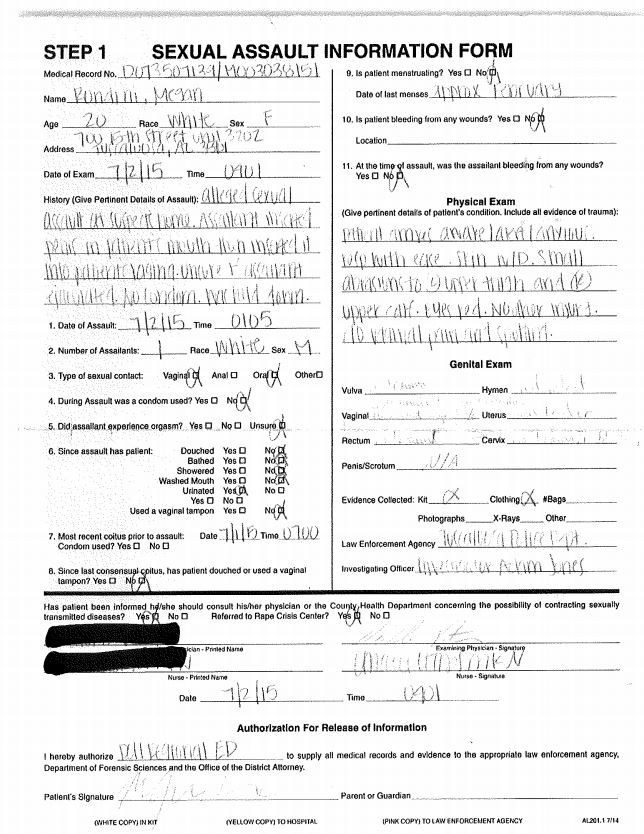

The roommates stayed with Rondini for the next few hours while nurses conducted an exam, collecting information for what’s known as a “rape kit.”

“She was freaking out,” the friend said. “She was very stressed and scared.”

The audio of the interview with her friend is posted below:

The nurse collected a urine sample, Rondini told her father in a text message.

Urinalysis results were not included in the exam report provided by DCH to investigators, Tuscaloosa County Metro Homicide Unit commander Capt. Gary Hood said.

The exam report is included in the information provided to The News. The nurse noted that Rondini arrived awake and anxious, and was breathing easily. Her eyes were red and she had small abrasions on her thigh and upper calf, which Rondini told investigators were from the wrought-iron fence. She had no other injuries, according to the report.

Hood said that information sent from DCH in rape cases doesn’t always contain urinalysis results.

“Urine samples are obtained by hospital personnel and tested and stored according to hospital protocols and procedures,” Hood told The News last week. “A urine sample was not included with the kit delivered to law enforcement, and law enforcement did not participate in any medical provider’s decision to draw, test or store urine obtained from Ms. Rondini.”

“Whether to order a urine test in a hospital setting is a private and confidential doctor-patient decision, protected by medical privacy laws,” he said. “No evidence has come to the attention of law enforcement indicating that the patient or her medical care providers requested or obtained a urine test. The observed memory and behavior of the patient at DCH did not suggest drug or alcohol impairment to any investigator and there was no other evidence indicating that a urine test should be requested. To date, no DCH medical record of any urine test has been submitted to the Tuscaloosa County Sheriff’s Office.”

Discussing the rape kit, Abernathy said: “In this case, both parties admitted participation in a sexual act, and identified themselves as the only participants in that act. A kit was not needed to identify a suspect, or prove that an admitted sexual act occurred. After Ms. Rondini advised law enforcement she wished to have the investigation terminated, due to a decision to proceed in a different manner, the kit has remained securely locked in evidence.”

Rondini family attorney Leroy Maxwell wrote in the federal lawsuit that the failure to test the urine “shut and locked the door on any evidence that would have established whether Megan had been drugged in addition to being raped.”

The friend who drove Rondini to the hospital said she was “rambling a lot,” and said Rondini told her she didn’t know how she ended up at Bunn’s home.

Tuscaloosa Police were called to DCH at 3:50 a.m. Investigators from the homicide unit, which handles all reported violent crimes in the county, arrived at 4:30 a.m. and took an audio statement from Rondini at 5:37 a.m.

The recording is posted below:

It was the first of three times that day that Jones asked Rondini whether she resisted or felt she was in danger. For someone to be convicted of rape in Alabama, prosecutors must prove forcible compulsion, and that “earnest resistance” on the part of the victim must be demonstrated before the element of forcible compulsion is deemed proven.

Forcible compulsion, according to the law, is defined as force that overcomes earnest resistance, or a threat that places a person in fear of immediate death or serious physical injury.

“Did you ever resist him?” Jones asked.

“I know he’s an influential person in Tuscaloosa and I didn’t want to be like, I didn’t want to burn bridges, you know, so I was trying to be really nice and be like ‘I need to go, my friends are waiting on me,” she said. Jones ended the interview two minutes later, as Rondini was crying.

The investigators went from the hospital to Bunn’s home.

6:30 a.m. – 10 a.m. July 2

Several investigators from the homicide unit went to Bunn’s house. He invited them in, and gave written consent for them to search. He initially told investigators that no one but Barksdale had been at his home. Within minutes, he changed his statement and gave a recorded interview.

Bunn said he didn’t remember Rondini’s name, but recognized her as someone he’d seen at Innisfree before.

“We had consensual sex, and went to bed and Josh Hastings woke me up, ringing my doorbell at 6:45,” he said that morning.

The investigators took more than 100 photos and videos of Bunn’s home, and found a spent .380-caliber shell casing in the Mercedes.

Click here to see all of the evidence photos and here to see a video of the home.

Barksdale gave a statement that he was drunk, that Rondini went with them willingly and that he didn’t hear anything after going to bed.

Hastings asked Bunn in the July 6 interview why he first said no one had been at his house that night. Bunn replied that he was confused when the officers first arrived and woke him.

“Once I had time…of course when y’all rang the door and I’m thinking the worst, I wasn’t thinking about that, but once y’all were there for a few minutes and I got time to kind of collect my thoughts,” he remembered Rondini had been there, he said. “At that time, to be honest with you, I didn’t recall.”

“Were you scared?” Hastings asked in the interview.

“Of course, yeah, sure,” Bunn replied. “Still scared.”

11:30 a.m.- 3:15 p.m. July 2

Jones interviewed Rondini for about three hours at the Tuscaloosa County Sheriff’s Office. They left the department after about two hours to visit her apartment and returned for a final hour of questioning. She told him toward the end of the interview that she didn’t expect to press charges.

Rondini was accompanied by Nesha Smith, a victim advocate who works for UA’s Women and Gender Resource Center, for the first two hours of the police interview.

Click here to see all interviews with Megan Rondini.

Rondini told her Smith was comfortable continuing the interview alone after the trip to the apartment. At one point, Jones spoke with Rondini’s father on the phone.

Rondini told Jones toward the end of the interview, after she had recounted her experience, visited her apartment and been questioned about the gun, that she didn’t want to press charges.

“To be honest with you, I’m pretty sure I’m not going to press charges at all,” she said. “I don’t want to make this a big to-do. I want to be done. I just want to move on.”

Before ending the interview, Jones asked whether she had taken medication or felt she had been drugged.

“I’m glad that they got a urine sample, but when I think of someone being drugged, I think of someone where they don’t remember the whole night, and I only don’t remember parts,” she said. “I don’t know if a drug can do that. I think of roofies, and you’re out.”

“I’m not doubting any part of your story,” Jones told Rondini. “The evidence there on the scene lines up with what you’ve told me.”

“I just feel like he has some advantage over me in this, and I don’t really understand why,” Rondini said. “I just feel like if this isn’t, I don’t know, like he’s getting the benefit of the doubt here because he’s a nice person and everybody likes him.”

“I’ll be honest with you, I don’t know him,” Jones said. “I haven’t gotten any orders from anybody above me that says ‘Hey, we need to sweep this under the rug.’ That’s what I tried to explain to your dad.

“We can’t allow money to influence the way we do our investigations. That’s just the way we do things. But that really stood out to me, because I felt like your dad was insinuating that.”

“He can be like that,” Rondini said. “I’m sorry. I made a big deal about it to him because I’ve seen how other people…but I didn’t make it sound like the police were going to do that, I was just saying he knows a lot of people.”

Jones encouraged Rondini to talk with her parents about her decision not to press charges.

“He’s a lawyer, he’s very hard-headed,” she said of her father.

“He wasn’t rude to me, I would just say matter-of-fact with certain things and I understand that, because you’re his daughter,” he said.

The interview ended around 3:15 p.m.

Since July 2, 2015

Rondini returned to Tuscaloosa for the fall 2015 semester, but withdrew after six weeks and moved back to Texas in October. She transferred to Southern Methodist University in Dallas, where she was living when she took her life in February 2016.

She returned to the Sheriff’s Office to collect her property on Aug. 25. She took the shoes police had recovered from Bunn’s home, but said she’d rather her clothing be destroyed.

Jones told her the case would be closed, and she said that she was looking into pursuing the case through a civil suit.

“Isn’t this going to be written down somewhere?” she asked. “That something happened, or that I said something happened?”

A Birmingham attorney representing the Rondinis had contacted the homicide office a few weeks prior, Jones said, and said he didn’t understand why they were no longer investigating Bunn for rape. The attorney later directed investigators to not contact Rondini, Jones said.

Even though Rondini said she didn’t want to prosecute, prosecutors presented the evidence to a grand jury for a final determination six months later. The grand jury did not issue an indictment. The prosecutors were prepared to present evidence for theft and breaking and entering a vehicle charges against Rondini, but never did because she had taken her life the previous week.

The BuzzFeed story and federal lawsuit came 16 months after Rondini’s death, which led to similar stories published by London’s The Daily Mail, CBS This Morning and other national publications and broadcasts. The resulting social media firestorm has been divided, with much of the anger directed toward Bunn, his family, the university and the Sheriff’s Office.

Online posts refer to Bunn as a “serial rapist,” although investigators told The News that he has never been named a suspect in any other reported sexual assault or rape cases in Tuscaloosa County.

Rondini’s attorney wrote in a motion filed in the lawsuit that a woman in 2012 reported that Bunn drugged and raped her, and that she is willing to provide testimony with her statements under seal for her protection.

“He was not a suspect in that case,” Tuscaloosa County Sheriff’s Office Division Chief Loyd Baker, who was commander of the homicide unit at the time, said this week. “He has never been named as a suspect in any sexual assault case here.”

Other online posts have personally attacked the investigators, because of what posters perceive as their attempts to protect Bunn from prosecution.

One woman posted, and later deleted, a wedding announcement of an investigator’s brother. She included a photo of the announcement listing the groomsmen and ring bearer, adding the comment “May you all burn in hell!” Another post included photos of the wives and children of elected officials, with similar comments.

Bunn has received death threats, called in to the business, said Bunn family attorney Ivey Gilmore. Tuscaloosa Police placed extra patrols near the office in the days following the BuzzFeed publication.

Groups that have formed to support the Rondini family held a march earlier this month, taking a route that started at DCH, traveled past Innisfree and ST Bunn Construction and ended at the Tuscaloosa County Courthouse. They’re planning future activities and outreach to support sexual assault victims.

In July, U.S. Rep. Ted Poe (R-Texas) and Rep. Carolyn Maloney (D-NY) introduced the bipartisan Megan Rondini Act, which would require hospitals to have a SAFE (Sexual Assault Forensic Examiner) available at all times, or have a plan in place to transfer victims to a nearby hospital staffed with one.

The federal lawsuit was filed in early July. Saying the Rondinis lack standing to assert a wrongful death claim, all of the defendants in the federal lawsuit have filed motions to dismiss the case, citing constitutional and case law.

The Rondinis claim in the suit that UA and Bell contributed to Rondini’s suicide by failing to provide her with adequate counseling, suggesting the Bunn family’s wealth influenced their actions.

Rondini attorney Leroy Maxwell wrote that UA was “deliberately indifferent” to Rondini’s rape claim, and created “an abusive and hostile educational environment for Megan, sufficient that she was forced to leave the campus, and was ultimately a cause of her loss of life.”

“The facts underlying the failures of UA and the other defendants to protect Megan and to prefer its relationship with a wealthy donor family are shocking,” Maxwell wrote in the lawsuit.

Birmingham attorney Jay Ezelle, representing UA and Bell, filed a motion to dismiss Tuesday, writing that it is “absurd” to suggest the allegations against the university had any connection with Rondini’s suicide.

“This case is not about the University of Alabama,” Ezelle wrote. “Whatever happened on the night of July 1, 2015, it is undisputed that the University had absolutely no involvement. Defendant Bunn is not an employee or student; his residence is not owned or controlled by the University; and the University was not a sponsor or participant in the activities that occurred that night, all of which took place off-campus.

“The University, just like Megan Rondini’s parents, were powerless to control whatever happened that night. Further, the asserted details of that evening, which have unfortunately been fodder for yellow journalism and social media sensationalism, have absolutely no bearing on the claims against the University or President Bell.”

Rondini was seen by three mental health professionals at UA, according to Ezelle, after her first visit with a counselor who said she couldn’t treat her because she knew the Bunns.

UA staff provided mental health counseling, personal advocacy, academic assistance, and psychiatric treatment, he said.

The suit claims that Abernathy didn’t ensure investigators were properly trained to conduct sexual assault investigations, and that the officers didn’t conduct a thorough or professional investigation.

Attorneys for Abernathy and Hastings noted that state law makes Abernathy, as sheriff, immune from suits for damages based on official acts, because he is an executive officer of the state.

“In addition, the amended complaint fails to allege that Deputy Hastings had any contact with Ms. Rondini, or had any reason to know that she would be suicidal seven months after she initiated a complaint. The plaintiffs’ claim for wrongful death unavoidably fails,” attorney Robert Spence wrote.

In the lawsuit, Rondini’s lawyer wrote that Jones didn’t ask Rondini questions that would incriminate Bunn, could prove whether she was drugged or about why she would have jumped from a window if the sex had been consensual.

Attorney Christopher McIlwain, representing Jones, said that the investigator’s line of questioning was to determine whether evidence supported a strong enough case to prosecute.

“Any law enforcement officer knows that a rape suspect’s criminal defense lawyer will put the victim on trial and attempt to poke holes in the alleged victim’s credibility and version of the facts,” he wrote.

“In essence, someone in the investigative chain must test the case by role-playing the expected defense strategy. An examination of the questions posed by Jones to the victim about which Plaintiffs now complain — they call it bullying and a reflection of bias — are precisely some of the questions victims face in court.”

“The Plaintiffs say all of Jones’ questions demonstrate bias, but they actually show he was doing his job,” he said.

The Rondinis have asked for a jury to hear the case, presided over by U.S. District Judge R. David Proctor.

They are asking for unspecified compensatory and punitive damages.