Landri Torrez, 28, barely recognizes the East Austin neighborhood where she grew up. Corner stores she frequented as a child and homes where family members and friends had lived since have been replaced by condos and restaurants, largely catering to young, white professionals.

The neighborhood school, Metz Elementary, where she and her husband met two decades ago and where their daughter now attends, has been among the few remaining anchors of the community, she said. With the Austin school district proposing to shutter the school and consolidating it with another campus by next school year, the loss of the only neighborhood she has ever called home is imminent.

“This is not the east side anymore. This is not home, and that hurts,” said Torrez.

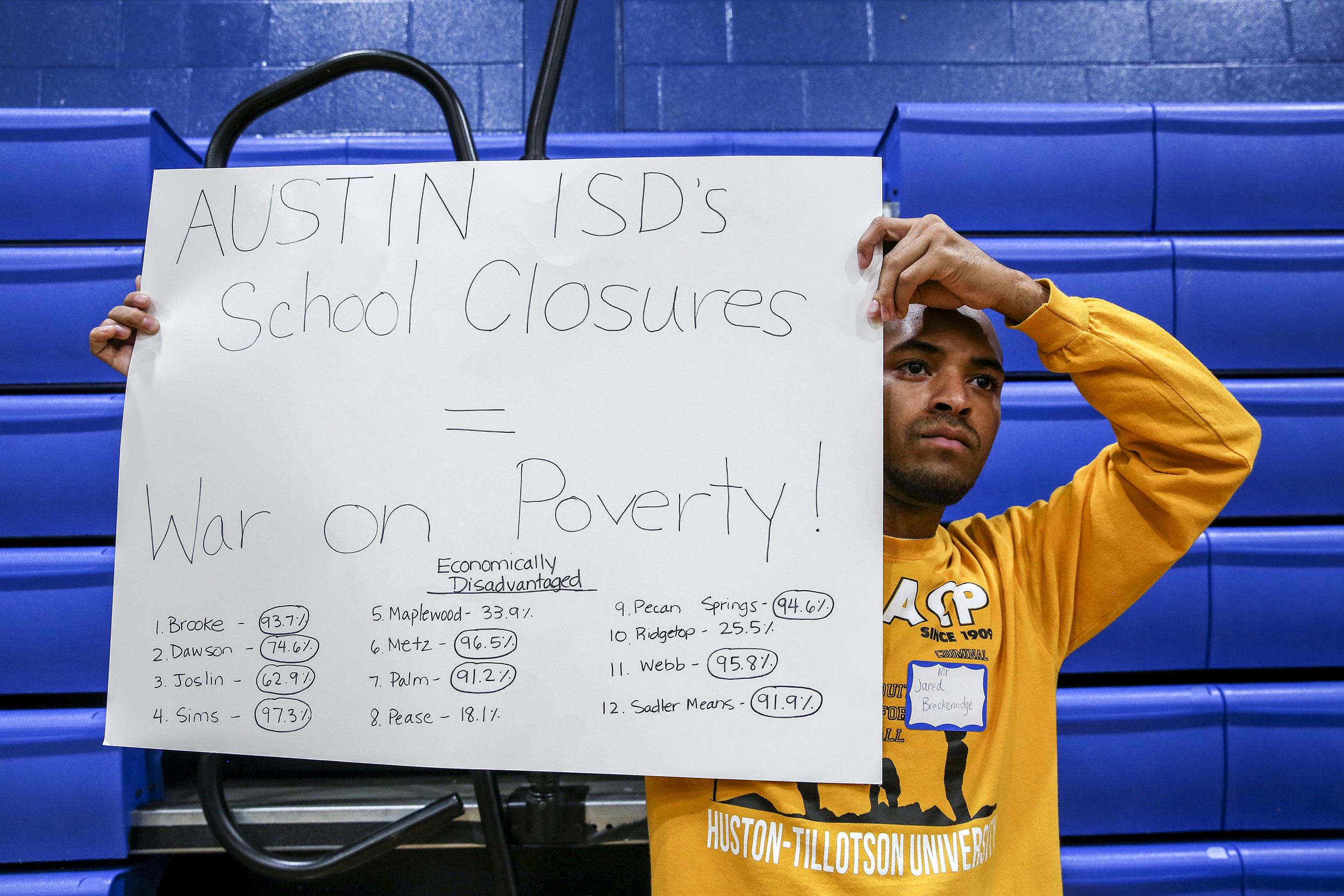

The Austin school district has proposed closing by the 2020-21 school year Pease, Metz, Sims and Brooke elementaries, the latter three of which are situated east of Interstate 35 and contain deep historical roots in Austin black and Latino communities. While district leaders have said the schools are underenrolled and too costly to maintain, many affected families told the American-Statesman they believe the district’s plan unfairly targets their communities of color, ignores their concerns and fails to acknowledge institutionally racist practices that have led to the problems at those schools.

District officials have also said they should have done more to make their plan, which also includes improvements to academic programs, more equitable.

In 2017-18, the latest data available from the state, 67% of students at the schools on the closure list were Hispanic, 16% were African American and 75% were low-income — much higher than the percentages districtwide, by as much as 22 percentage points. While Hispanic students make up the largest share of the students at the four schools, black students are more disproportionately affected by the closures.

Austin district leaders have acknowledged their plan to close to schools did not focus enough on equity — ensuring that each child from all racial backgrounds develop their full academic potential. Although they have performed an equity analysis on whether academic changes in the plan would harm or benefit black, Latino and low-income students, among other student groups, officials have yet to conduct a similar analysis of how school closures would benefit or hurt those vulnerable student populations.

Had the school board directed district officials to develop a plan focused on addressing the district’s inequities and not solely on remedying facilities and financial problems, the schools on the closure list might have looked differently, and the timeline for implementation would not have been so rushed, said Stephanie Hawley, the newly appointed Austin school district’s chief equity officer.

ALSO READ: Sims' closure raises fears Austin district will further drive away black students

“Equity is all about the students, the communities that are on the margins…We all are interested and are committed to the well-being of the children, but you have to start there. Equity work starts there. Facilities and programs don’t always begin with the well-being of children,” Hawley said, who has requested her colleagues conduct an equity analysis of closing schools.

The district in September originally released a plan that would have closed 12 schools, most of them on the east side. After holding a series of community meetings, on Nov. 1, district officials announced they pared the list down to four schools that would be consolidated with other student bodies. All schools except for Pease, an all-transfer campus whose students will return to campuses in their own neighborhoods, would be consolidated at newly built modernized campuses. The board is expected to vote on the most recent iteration of the plan Nov. 18.

Why history matters

Among the steps to making the district’s plan more equitable is to understand the history of the schools on the closure list, said Rickey Lowe, a research associate with the University of Texas’ Institute for Urban Policy Research and Analysis.

“We don’t want to repeat historical practices” that have hurt black and Latino communities, Lowe said.

Some East Austin schools are underenrolled because they were built smaller and in close proximity to each other to accommodate racially segregated student bodies. The 1928 City of Austin plan forced black communities into the east side by barring public services outside of it.

Metz was built in 1916 in an area considered the “most desirable Mexican section,” according to documents from the Austin History Center. The school had a modest share of Mexican-American children — 27% in 1934 — but after Zavala Elementary School was built four blocks away to accommodate Mexican-American children, Metz’s percentage of such students dwindled to about 10% in 1940.

Shortly after World War II, the abundance of building supplies and desegregation of schools led to white flight of the neighborhood, leading Metz to become majority Hispanic, which is still the case today.

Because Metz had been a primarily Hispanic school, documents from the history center show that school officials had to fight for the district to invest in programs at the campus as well as for facilities maintenance. A lawsuit filed in 1987 accused the district of deliberately withholding “necessary enrichment and compensatory academic programs for minority children, delayed repairs to school buildings in minority neighborhoods and failed to provide adequate equipment to those schools,” according to a summary of the lawsuit found in the history center’s archives.

Paul Saldaña, a former Austin school board member and an activist for campuses in the city’s eastern crescent, said closing east side schools are forcing communities to pay for the sins of the district’s past.

“Of course schools east of Interstate 35 are going to be older and maintenance-and-operation is going to be more expensive, but that’s why you have to take the history into account,” Saldaña said.

Saldaña said those inequities persist today.

While on the board, Saldaña said he has watched wealthier white families, many of whom live west of Interstate 35, receive stronger academic programs, more experienced teachers and better facilities maintenance.

Look at differences in test scores between white children and their black and Latino peers to see how inequitable practices by the district have affected students, he said.

Last school year, 76% of white students in the Austin district met grade level on state standardized tests, while 34% of African American students and 41% of Hispanic students met grade level.

While district administrators have often pushed the narrative that families of color are fleeing Austin because they can’t afford to live in the city, UT researchers have found that black families have also left Austin for better educational opportunities.

Lowe said closing East Austin schools could repeat historical city and district practices of driving out black and Latino families by failing to place students in high-quality educational settings. Modernized campuses don’t guarantee a better education, he said.

“If … the schools are not prepared to accommodate them, you will see an outmigration of black and Latino residents of this area to schools in suburban cities or to charter schools,” Lowe said. “In that context, AISD is potentially contributing to more displacement of black and Latino communities and students. That repeats history.”

Feeling targeted

Ruth Tovar’s landscape contracting business sits in a corner of her parent’s East Austin home. Tovar, vice president of the Brooke Elementary Parent Teacher Association, grew up in the home, less than a mile away from the school where two of her four children are in kindergarten and fifth grade.

If closed, Brooke students who live north of the river would attend Govalle elementary school about a mile away and those who live south of the river would attend Linder elementary, about four miles away. Documents released by the district last week kept Brooke, where 85% of students are Hispanic, on the closure list tentatively, while district officials “continue a community discussion” about the school. But Tovar isn’t convinced the school is saved. Instead, she’s considering homeschooling her remaining school-age children, “until they get to middle school.”

“It's a form of grief, for sure,” Tovar said. “For people who aren't parents, or who haven't been in this situation, maybe they don't understand that, but it feels like a loss.”

Brooke has maintained the Hispanic culture of the community. Murals in the hallways painted by the late Austin artist Raúl Valdez depict Chicano children learning, painting and dancing. The school offers students opportunities otherwise unavailable to them, like ballet folklorico, acoustic guitar and beekeeping lessons as well as the ability to grow produce in campus garden plots and selling their products in a farmer’s market the school hosts twice a year.

Brooke also has transformed into a hub for services. A rack of free clothing sits at the school’s entrance for families and the school’s parent support specialists will sometimes organize food pantries. The specialists also connect families, many of whom only speak Spanish, to services to pay bills, to find transportation and to learn English.

“Spanish-speaking families will be affected mostly (by the closure). Unless the incoming schools are very welcoming and have support in Spanish for them, they will have a hard time building relationships and trust,” said Brooke Principal Griselda Vargas.

Vargas said requiring her Spanish-speaking families to change their routines, like picking up and dropping off their children, after a closure is not an inconvenience; it hurts their quality of life.

Guadalupe Hernandez Peralta is a grandmother at Metz, which is slated to be closed and moved to the new Sanchez Elementary School campus about a mile west toward Interstate 35. She currently walks two blocks to pick up her two grandsons, who are in first and second grade.

“I don't know what I'll do the day they close the school,” Hernandez Peralta said in Spanish. “I don't have a car. I always have to walk, whether it's in the cold or in the rain, to and from.”

Can closures be equitable?

Lowe, the UT researcher, said studies of closures that have happened across the country have mostly affected children of color and have not always improved educational outcomes for them.

Closures of Houston public schools between 2003 and 2010 that disproportionately displaced black students were not associated with higher achievement, save for small, short term gains in math, according to a 2016 UT policy brief.

Contemporary school consolidation efforts often fail to deliver the promised enhancement of academic offerings, according to a 2011 study published by the University of Colorado-Boulder.

Instead of closing schools, Saldaña would have preferred the district redraw school boundaries to further integrate Austin schools, but district leaders, including board members who represent the west side, have avoided the politically charged process, he said.

To analyze if closures and consolidations can be done as equitably as possible, the district leadership has more to do, Hawley suggested. As a part of the updated version of the school closures and changes plan released Nov. 1, district administrators conducted a basic equity analysis of each change they want to make, including the closures. Officials also stated in the analysis that “discrimination and favoritism in the district have resulted in segregated schools” and that “Austin ISD has been failing to meet the social, emotional physical and academic needs of historically underserved students.”

Although she applauds the district for naming those problems, Hawley is suggesting the next step should be an equity analysis of just the school closure proposals alone that ask more nuanced questions like, what will be the impact of the closure on the district for seven generations and what additional costs might emerge from the closures.

If the district still needs to move forward with closures, the district must have leaders who buy into and trained in achieving equity, which has already started, Hawley said.

“We’ve put a toe in the water with the little bit of training, but there will come a point where our leaders can’t think any other way except for how does this impact the most marginalized people in our system,” Hawley said.