My electricity was disconnected today without any notice and we are also under a heat advisory in Dallas …

But no one called or emailed to let us know how much or where to send payment to. So they cut off our power in the 100 degree heat. I called to see if there was any way they could work out a [redacted][redacted] so we could have air and our milk wouldn’t go bad. Or that we could even take a hot shower.

I have lost over $200.00 worth of groceries that I just brought yesterday.this company puts profit over people …

… it is extremely hot. My family and I had to sleep in the car, not to mention all the food …

Cp states that he has a new born and it is too hot for the baby. Cp doesn’t understand why his service was disconnected …

Found unresponsive in trailer home with no AC; window unit in bedroom where found not operational …

… lived alone, last seen 4 days previously; did not want to turn on AC in fear of her electricity bill getting too high.

Died at home; no ac running; 2 fans in living room; daughter said AC went out the day before and was in process of getting it repaired …

Today they cut my power off I am $[redaction] positive and I called they keep saying my power will come back on in a few minutes, it has been over 2 hours! The forecasted heat today is 103 degrees, it’s 101now! How is it even legal for them to cut anyone’s power off in this heat! This is the 4th time they have cut my power off when I have money on my account in the last week!

I’m in Houston and it’s hot, not only that I have health issues. PLEASE HELP!

Complaints filed with the Texas Public Utilities Commission

Death reports from Texas medical examiner offices

Back to top

hostage to heat

Texans fall victim to sweltering summer temperatures as regulators ignore skyrocketing power cutoffs

DALLAS — The ambulance raced through the streets of South Oak Cliff on a sweltering August afternoon, coming to a stop in front of an aging duplex.

Paramedics gathered around Clyde Jackson, 66, and helped him walk shakily to a waiting gurney. On the seventh day of an August heat wave that brought two weeks of 100-degree days to North Texas, Jackson had gotten dizzy, overcome by rising temperatures inside the home.

Clyde Jackson, 66, is taken by ambulance from his home on Fordham Road in the South Oak Cliff neighborhood in Dallas after he was overcome by the heat. Jay Janner | American-Statesman

“It just got too hot for him,” said his niece, Katrina Johnson. Affording enough electricity to stay safe hasn’t been easy for the extended family, which shares a duplex. The family has been trying to conserve energy after the power was cut off several times in recent years. As paramedics rushed Jackson away, his relatives worried about another disconnection.

Their bill was already a month late, and Johnson said she wasn’t sure how they would pay off their $340 balance, especially as searing temperatures continued.

Katrina Johnson adjusts her single window unit air conditioner at her home on Fordham Road in South Oak Cliff moments after her uncle was overcome by the heat and taken to a hospital. Affording enough electricity to stay safe hasn’t been easy for the extended family, which shares a duplex. Jay Janner | American-Statesman

“It just got too hot for him,” said Katrina Johnson, standing in the kitchen of her home in South Oak Cliff moments after Clyde Jackson, her uncle, was overcome by the heat and taken to a hospital. Jay Janner | American-Statesman

A GateHouse Media analysis of 320 medical examiner reports across the state, obtained through Texas Public Information Act requests, shows that more than 100 Texans died of heat-related causes inside their homes over the past decade. Many were rationing their electricity in an attempt to avoid massive summertime bills.

So far, though, the family has been luckier than some of its neighbors.

Rising summer heat has struck this southern Dallas neighborhood perhaps harder than any other part of Texas. In the past four years, neighbors in the eight-block radius surrounding the Jacksons have requested an ambulance for heat-related illnesses more than a dozen times. Nine people in the 75216 ZIP code have died of heat-related causes since 2010.

As Texans fell ill and died, state regulators and lawmakers failed to provide relief, turning a blind eye to skyrocketing summertime disconnections carried out by private electricity companies and chipping away at protections for low-income customers.

The six-month GateHouse Media/American-Statesman investigation found:

Among the two-thirds of Texans who receive power from private companies, summertime disconnections for nonpayment soared 117% from 2009 to 2018. An internal tally of summertime disconnections, obtained through a Texas Public Information Act request, shows private electricity providers shut off power nearly 4.4 million times during the summer months from 2014 to 2018.

In the summer of 2015, private providers cut customers’ power 987,000 times, the most during the time studied. In 2018, from June to September, providers cut customers’ power 834,000 times. In deregulated Texas, the disconnection rate is far higher than in other states that report disconnection data and dwarfs that of municipally owned utilities such as San Antonio’s CPS Energy and Austin Energy.

In 2009, the Texas Public Utility Commission, the agency charged with overseeing private electricity companies, stopped publicly tracking and analyzing disconnection numbers and rejected calls from consumer advocates to halt summertime shutoffs.

More than 1,100 informal complaints filed with regulators about disconnections from 2015 to 2018 show summertime shutoffs have hit legions of vulnerable Texans, including those with medical problems, small children and elderly people. Texas residents have suffered heat-related medical issues and in some cases been forced to sleep in their cars to get relief, the complaints show. Elderly residents have been left without power for days during brutal heat waves. And the complaints show that disconnections happened on days when temperatures reached as high as 106 degrees.

As private energy disconnections approached 1 million per summer, lawmakers eliminated a state utility assistance program that provided tens of millions of dollars a year in direct utility assistance to needy Texans. The problem of rising disconnections never caught the attention of legislators, and no government entity is examining the public health fallout.

Consumer advocates say the findings raise questions of whether state regulators are doing enough to keep Texans alive as summers become increasingly brutal. A system that regularly permits nearly 1 million summertime disconnections is clearly dysfunctional, they say.

“Electricity service, particularly in hot states like Texas, is an absolute necessity of life,” said John Howat, senior energy analyst at the National Consumer Law Center. “It’s not a discretionary item that can come and go. These high disconnection numbers … should be viewed as a call for action to protect customers’ access to service.”

The Public Utility Commission did not identify any action it has taken in response to the growing disconnection numbers.

The agency hypothesized that the shutoffs rose because of so-called smart meters, which allow companies to remotely disconnect customers, and population growth. The state’s population increased 20% in the years that disconnections rose 117%. The agency pointed to its protections against shutoffs, including a prohibition against disconnections during heat advisories, as well as its advocacy for customers who file complaints, and noted that “customers wishing to maintain the consumption of a commodity provided them by a business are not without options.”

Vici Potts visits the grave where her late aunt, Rue Nell Swaner, is buried in Wylie. Swaner’s power had been cut off in the hottest part of an extremely hot year, Potts said. Nick Wagner | American-Statesman

Consequences of cutoffs, rationing

Rue Nell Swaner remained fiercely independent as she hit her 80th birthday. She insisted on staying in the southern Dallas home where she had lived alone for decades after her husband died, and she still drove her classic Lincoln Mark V like a “bat out of hell,” according to her great-niece.

In early August 2010, Dallas police forced open the front door of Swaner’s home, across the Trinity River from the Jacksons’ duplex in South Oak Cliff, and found Swaner on the bedroom floor. Officers tried to turn on the air conditioning and the lights.

“It is unknown how long the electricity has been turned off,” the investigative report says. There were no working fans, and all the windows were closed.

Swaner’s niece, Vici Potts, said she thinks her aunt had developed dementia and might have forgotten to pay her electric bill.

“That was an extremely hot year, and that was the hottest part of the year,” Potts said.

Swaner was one of two Dallas residents found dead after disconnections that year.

Vici Potts holds a portrait of her late aunt, Rue Nell Swaner, who was found dead in August 2010 in southern Dallas with her electricity not working. Potts said she thinks Swaner had developed dementia and might have forgotten to pay her electric bill. Nick Wagner | American-Statesman

Two days after her body was discovered, police found a 52-year-old man in his apartment complex north of downtown Dallas. He had “failed to pay his electric bill and the electricity was turned off,” the coroner’s report says.

The next year, when record summer temperatures and drought swept through Texas, six residents in the South Oak Cliff area died in their homes.

“One day you are delivering their mail. The next day they are dead,” said the neighborhood mail carrier, who asked not to be identified because he hadn’t been cleared to speak by the U.S. Postal Service.

As he walked past silent air-conditioning units on a scorching August afternoon, the mail carrier worried about 2011 repeating itself. “I think about it. I pray about it,” he said. “Some people really do need help.”

A mail carrier walks his route past storm-damaged trees in South Oak Cliff. Some homes’ air-conditioning units are silent as residents try to save money and avoid a power cutoff. Jay Janner | American-Statesman

Dallas’ 75216 ZIP code is an extreme example of the dramatic public health toll of rising temperatures and lax public oversight of private electricity providers across the state. In the past three years, residents in the 75216 ZIP code have submitted 2,946 requests for help paying utility bills through the Texas Health and Human Services Commission’s 211 help line, more than anywhere else in the state.

How to get help: Click here

In this neighborhood, where many streets are lined with small, single-story homes, many with aging window units sagging off of exterior walls, about 37% of the ZIP code’s population lives in poverty — double the state average. Nearly 60% of residents are African American, and 18% are over 60, according to census data.

Ellis Cunningham, 74, mows the lawn at Deliverance Baptist Church where he is a deacon in the South Oak Cliff neighborhood in Dallas on a very hot August morning. Jay Janner | American-Statesman

Elderly neighbors who live alone, many on fixed incomes, have been hit especially hard. Those whose electricity hasn’t been cut off for failure to pay often ration their air conditioning to save money and prevent the scary and costly specter of losing power completely. But that has also had tragic outcomes.

On Aug. 2, 2011, 73-year-old Bettie Mae Lawrence died in her home on a day when temperatures reached 107 degrees. Coroner investigators found a silent window unit. They flipped the machine on, and cool air came out. Later, a cousin told investigators Lawrence refused to run the unit, “perhaps to save money.”

A week earlier, police found Alice Simmons, 76, dead inside her home, where temperatures exceeded 100 degrees. Simmons’ air conditioning unit also was off. Her brother told investigators she “never used the AC whatsoever.”

Medical examiner reports indicate this sort of rationing contributed to deaths throughout the state in recent years.

Utility assistance workers say rationing is a common way to avoid not just high bills, but the ramifications of a disconnection. Those who survive the brutal heat of Texas summer without electricity often face a cascade of penalties.

After a disconnection, a customer can lose deferred payment plans and be forced to pay additional deposits and hefty fees, assistance workers say.

According to a February study by Texas ROSE, a ratepayer advocacy organization, private electric providers charge an average of more than $70 in disconnection-related fees.

“These fees exploit seniors, customers on fixed incomes and other economically fragile customers living paycheck to paycheck,” the report concluded.

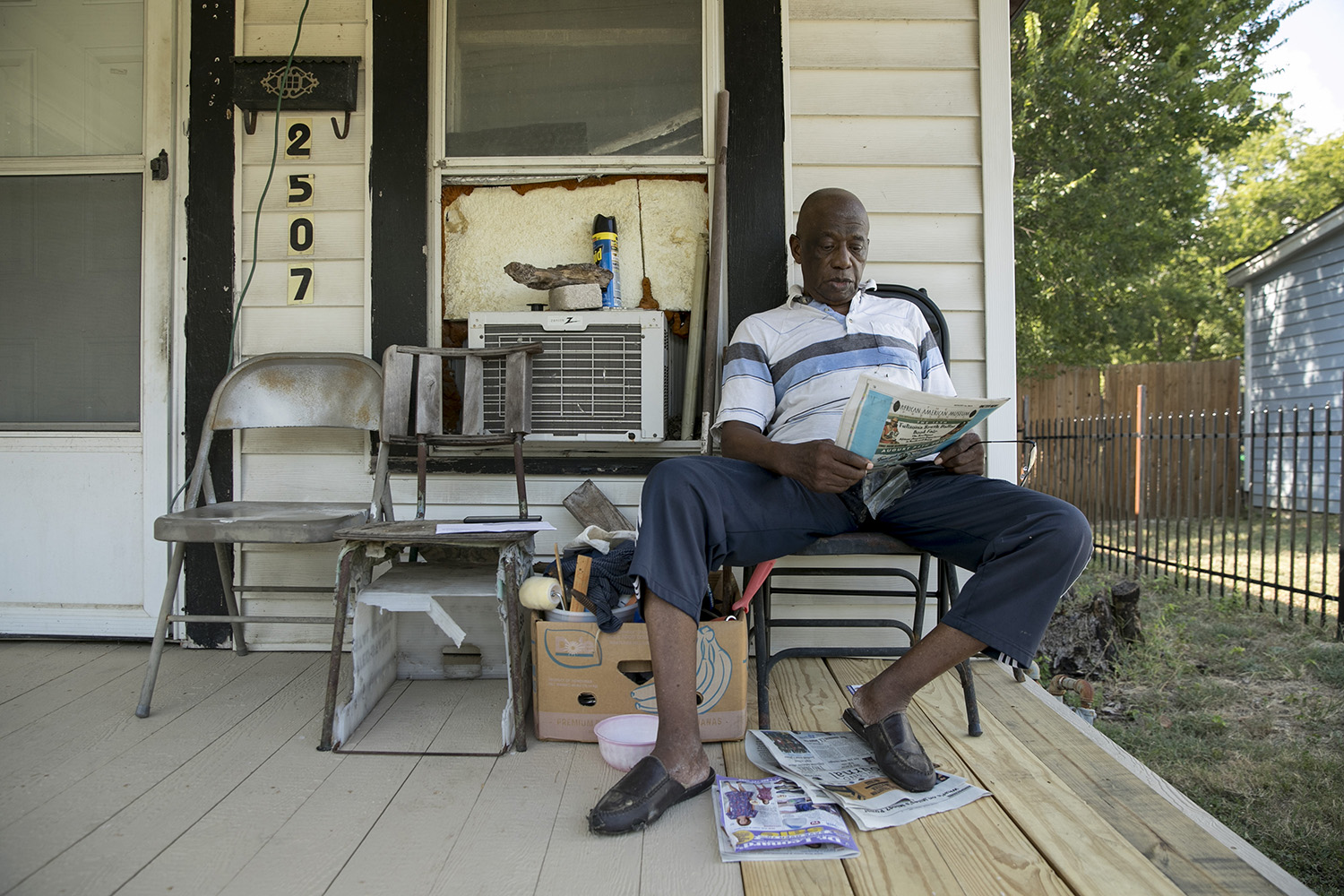

Ivy Mathis, 64, sits in the shade behind his home on Maryland Avenue in South Oak Cliff last month. Mathis spends his summers trying to beat the heat while keeping the electric bill manageable. Jay Janner | American-Statesman

Disconnections skyrocket

On a mid-August morning, Ivy Mathis sat on a folding chair in a nook of shade alongside his sister’s house in South Oak Cliff, drinking his morning coffee from a plastic foam cup. The shade holds until about 11 a.m., when the creeping sun sends him to a table under a leafy tree in the backyard.

Mathis spends his summers trying to beat the heat while keeping the electric bill manageable.

His power has been cut before, and he’s keen to avoid that situation again.

“If it goes out, you hope you have screens on the windows,” said Mathis, 64, who grew up on a farm in eastern Louisiana, helping his parents harvest cotton. “You open the windows like we did in the old days. I know what that life is like.”

Mathis is one of perhaps millions of Texans who’ve been disconnected in the past decade by private electricity companies as regulators have looked the other way.

From 2004 to 2009, the Public Utility Commission produced reports analyzing disconnections during summer months at the request of former state Rep. Sylvester Turner, D-Houston, who led a largely unsuccessful fight for greater consumer protections. When Turner stopped asking for them, the reports stopped in 2009, agency officials said.

Turner, who is now the Houston mayor, did not respond to requests for comment.

As Dallas’ skyscrapers loom in the distance, people walk along Idaho Avenue in South Oak Cliff. Rising summer heat has struck this neighborhood hard. Jay Janner | American-Statesman

For years, groups like AARP have said the climate protections don’t go far enough. Even without heat advisories, temperatures in Texas can be too high for people to live safely without electricity.

Scores of customer complaints, obtained through public information requests and heavily redacted by the agency, indicate existing climate protections are failing many Texans.

On Aug. 21, 2018, a Round Rock customer’s electricity was cut off on a day when temperatures reached 102 degrees, just short of triggering a heat advisory.

“It is inconceivable that a company would feel compelled to turn the power off to any household during some of the hottest months in the state of Texas,” the customer’s mother told regulators, who concluded Pennywise Power had followed state rules.

In the summer of 2009, private companies cut off power for nonpayment 385,129 times, according to an unpublished, internal commission tally obtained by GateHouse Media. In the decade that followed, which featured the hottest 10 years in the state’s history, such summertime disconnections exploded in Texas.

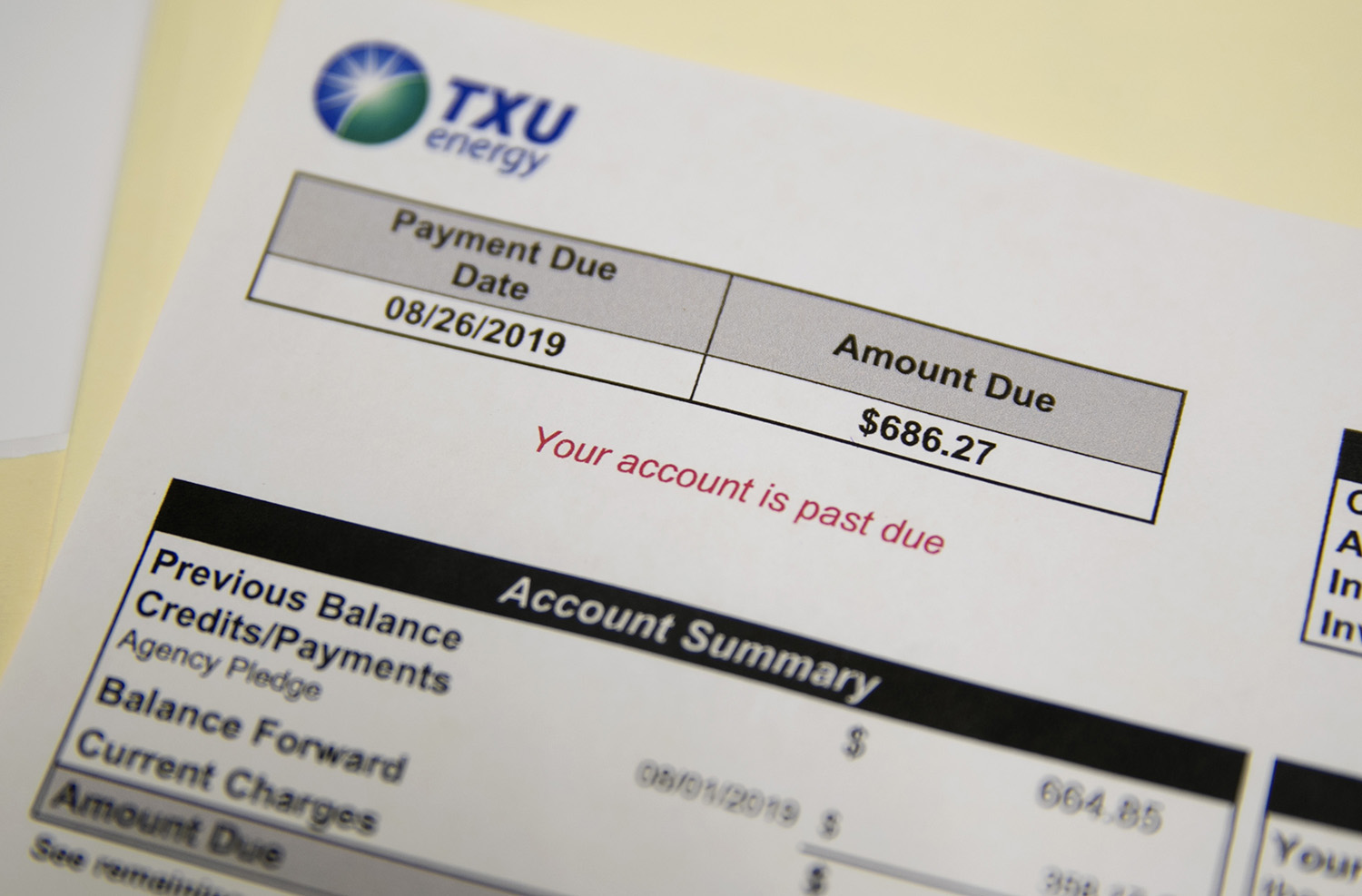

This past due TXU Energy bill was sent to a client of Caritas in Waco in August. Some private utility companies, including TXU, have their own assistance funds to help low-income Texans, but many of the state’s 50-plus private providers do not, according to assistance providers. Jay Janner | American-Statesman

By 2015, disconnections had reached nearly 1 million. Last year, private companies cut the power 834,000 times from June to September.

But because the commission did not report the numbers, the disconnections and the thousands of Texans who sweltered in the heat as a result remained far off the radar of lawmakers and consumer advocates.

Tim Morstad, associate director of advocacy with AARP Texas and a former member of the Texas Office of Public Utility Counsel, which is charged with advocating for ratepayers before the utility commission, said the agency should be regularly analyzing disconnection data and reporting it to lawmakers.

“A dramatic uptick in disconnections should be a red warning flag for state officials,” he said. “Protecting utility consumers is the core purpose of the Public Utility Commission. How can it protect the public if it doesn’t regularly collect, analyze and share electricity disconnection data?”

The commission has rules aimed at protecting Texans from high heat. The agency prohibits shutoffs during National Weather Service heat advisories, which are triggered in most of the state by temperatures of 103 to 110 degrees. It also prohibits disconnections on weekends and holidays.

In August 2017, a Stream customer told the agency: “My family and I had to sleep in the car. … This is life threatening because of the hot temperatures in Texas.”

In July 2018, during a deadly heat wave that killed at least 17 across the state, members of a family using Gexa electricity told regulators they were cut off after not paying a bill that was $300 more than anything they’d previously received. “What is particularly egregious about this violation, aside from the fact that we had no prior notice, is that this occurred at a time when average temperatures are well above 100 degrees and we have a baby in the house.”

Complaint data show Stream Energy, TXU, Ambit Energy and Direct Energy have received the most disconnection-related complaints since 2015.

A spokeswoman for Stream said the company follows agency rules on disconnections and works to avoid power shutoffs.

But it is impossible to know which companies perform the most disconnections, where they take place or which customers are most affected, because the utility commission did not release such data, citing concerns about the companies’ competitive secrets.

Agency officials say disconnection-related complaints have decreased in recent years, a fact they attribute to smart meters that allow for faster reconnections.

The commission has investigated companies for violating the prohibition on disconnections during weather advisories. In 2014, it found that Direct Energy initiated disconnections for nonpayment against 252 customers during an extreme weather emergency.

Most of the company’s requests for disconnection never went through, most likely because the electricity transmission companies that perform disconnections declined to cut the power due to a weather advisory. But 10 customers were shut off, including one who was without power for 36 hours, according to documents received through an open records request.

As a result, Direct Energy “implemented more efficient internal controls” and paid a $220,000 penalty, under a settlement with the commission.

Other investigations show that improper disconnections might be routine for some companies. The agency found Houston-based Spark Energy issued disconnection notices on weekends and holidays, both prohibited under state law, more than 14,000 times in 2017.

The company contended that the improper disconnection notices weren’t carried out and made changes to its system. The company paid a $90,000 penalty.

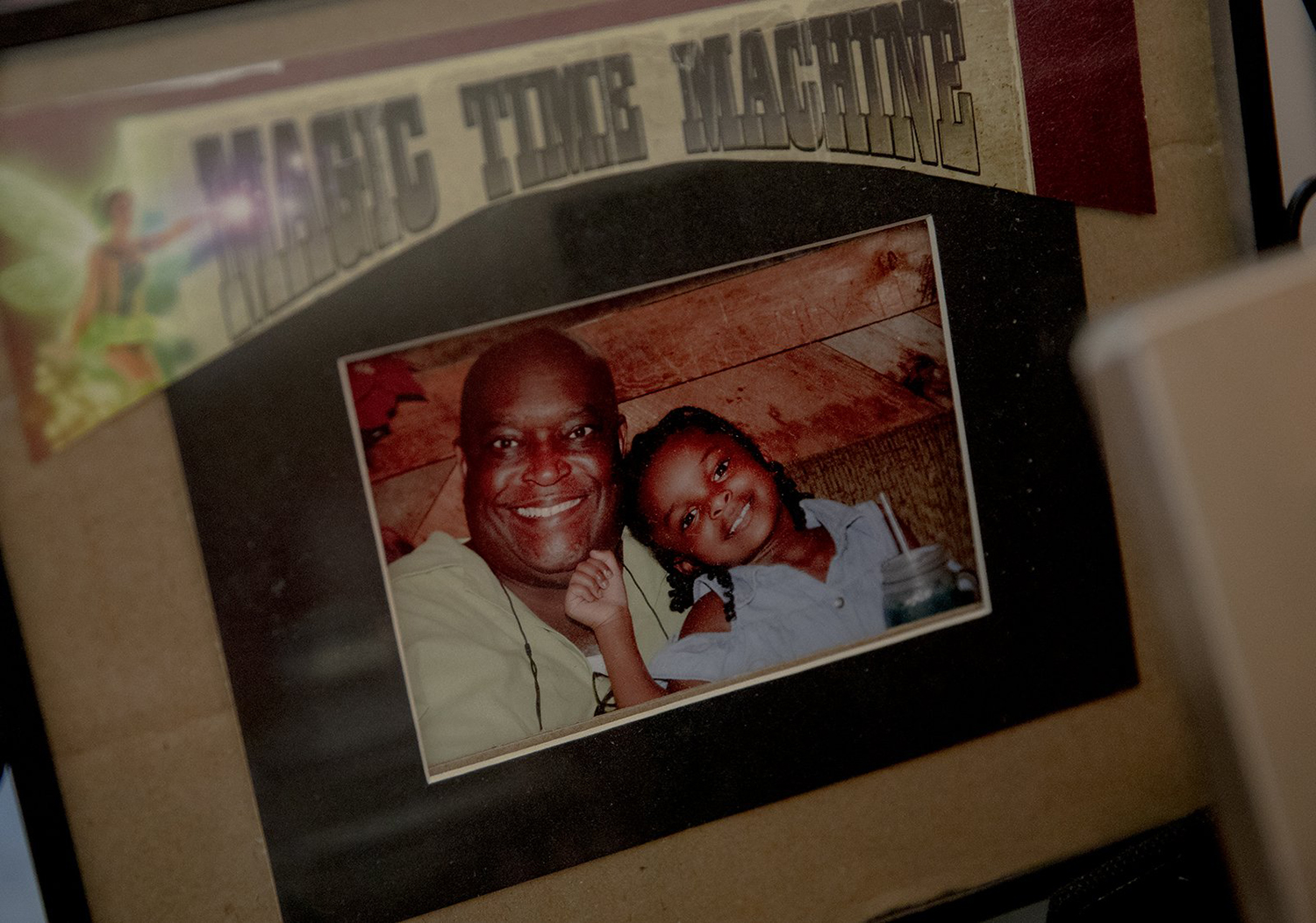

A photo of Carl King with his daughter, Carissa. Nick Wagner | American-Statesman

Assistance fund, protections eliminated

Carl King’s first thought when he got a disconnection notice in late July was of his 5-year-old daughter.

“I would have had to make provisions to make sure I had a place to send her,” the South Oak Cliff resident said. “If it was just me, I could work through that. You lose the power; all the food goes bad. I didn’t want to put her through that situation.”

King, a former IT worker and community activist in Dallas, had recently lost his job, and an unemployment check of around $1,500 a month left little to pay a $500 utility bill. “I said, ‘I’ll catch up next month.’ But you miss one month, it just gets to be a snowballing situation. You’re just trying to survive at that point.”

South Oak Cliff resident Carl King rations his electricity. He sets his thermostat to 80 during the day and turns it down to 75 when his 5-year-old daughter goes to bed. Once she’s comfortable, he turns it up a couple of degrees. Nick Wagner | American-Statesman

With utility assistance from the Community Council of Greater Dallas, he was able to pay his overdue bill, but this summer, he started rationing his electricity. He sets his thermostat to 80 during the day. He turns it down to 75 when his daughter goes to bed, and once she’s comfortable, he turns it up a couple of degrees.

Utility assistance workers say that scenario plays out for millions of low-income Texans every summer.

Over the past decade, lawmakers and regulators have eliminated both money and rules to protect low-income Texans.

Lawmakers in 1999 created Lite Up Texas, a utility assistance fund meant to ease the transition to a deregulated energy marketplace. The fund paid for a sometimes significant portion of low-income Texans’ bills.

The program rarely worked as intended. The Texas Legislature regularly raided the fund to balance the budget, even during some of the state’s hottest and deadliest summers. In 2011, the state’s hottest summer ever, lawmakers diverted tens of millions of dollars to avoid a budget shortfall.

“Essentially, it is stealing,” Turner, then a state representative, told the Houston Chronicle at the time. “They are using low-income and senior citizens’ money to maintain their pledge” not to raise taxes.

Former Gov. Rick Perry suggested eliminating the fund in 2007, arguing that the money wasn’t being used for its intended purpose.

Finally, after years of using the assistance money as a kind of piggy bank to balance the state budget, lawmakers in 2013 and 2015 filed legislation to shut the program down by 2017. Advocates say there was no discussion of the skyrocketing disconnections, which reached nearly 1 million during the 2015 summer — or the Texans suffering as a result.

With the fund’s demise in August 2016, poor Texans’ only recourse for assistance is a flagging federal program that currently reaches only about 6% of eligible Texans and is targeted for elimination by the Trump administration.

Some larger private utility companies, including the energy giant TXU, have their own assistance funds to help low-income Texans, but many of the state’s 50-plus private providers do not, according to assistance providers.

After Lite Up was eliminated, the PUC also got rid of the protections it offered, arguing it believed that was lawmakers’ intent.

In a move that caught advocates by surprise, the commission eliminated requirements that private electricity companies provide low-income customers with deferred payment plans, the ability to pay deposits over two months and an exemption from late fees.

The agency concluded the move would free companies to “compete for the business of low-income customers rather than being mandated to do so.” Officials claimed that several companies voluntarily maintain elements of the old requirements but couldn’t say how many.

Consumer groups have sued the utility commission over the changes.

Randall Chapman, an attorney representing ratepayers in the case, said the commission’s move is the latest in a series of decisions that have hurt low-income Texans.

Between 2007 and 2009, the commission rejected petitions to implement summertime moratoriums on power shutoffs after agreeing to a partial ban in 2006.

“The fact that the temperature, and with it, electric bills, increase in the summer months should come as no surprise to anyone,” then-PUC Chairman Barry Smitherman, said in 2009.

In 2010, the agency implemented a controversial policy of “switch holds” on delinquent accounts that would prevent customers from getting service from a new company before paying off their debt with their current company. Private companies said they needed the rule to protect themselves from high levels of bad debt due to unpaid bills.

AARP warned that under the new policy, “households can be held captive by their retail electric provider and stranded without power — indefinitely — until their entire outstanding balance is paid off.”

That prediction is borne out in complaints to the agency.

In September 2018, a First Choice customer begged the agency for relief from a switch hold: “This has left my 7-year-old daughter and I without electricity. I have pled with them to remove this switch‐hold and to bill me for the remainder. I was met with refusal and disrespect.”

Joppa, a former freed slaves’ settlement in the Dallas area, swelters in the midst of a rail yard, the Trinity River and a highway. Jay Janner | American-Statesman

Texas lawmakers not asking questions

The neighborhood of Joppa, a former freed slaves’ settlement, sits in the shadow of Dallas skyscrapers. In the northeast corner of the 75216 ZIP code, it is hemmed in by a rail yard, the Trinity River and a highway.

Montez Ashby, 24, said a lack of tree cover in his neighborhood leads to high temperatures inside his home, where his mother experienced what Dallas Emergency Medical Services called a heat-related emergency two years ago.

“There’s no afternoon shade,” he said, standing on his porch on a recent August day when temperatures rose into the triple digits. “The sun is beating up my house right now. By 5 or 6, my whole house is hot; I have to come outside.”

Andre Jones, 56, wipes his face outside his home on Fordham Road in the South Oak Cliff neighborhood in Dallas on a very hot afternoon. Jay Janner | American-Statesman

Frank P. Riley Jr. at his home on East Louisiana Avenue in the South Oak Cliff neighborhood. “Summers are getting tougher. It’s getting hotter, to me. I used to work outside at a furniture upholstery place in the summer. Now I can’t stand to be outside any more. It’s so much hotter than it used to be.” Jay Janner | American-Statesman

Heat emergencies are a regular part of summer life in the 75216 ZIP code, which had 246 EMS calls for summertime environmental exposure from 2008 to 2017, more than anywhere else in Dallas. The average Dallas ZIP code had 59 calls.

The state health department said reporting of heat-related emergency calls is so inconsistent, it was unable to provide any statewide data. But Texas Public Information Act requests to emergency medical services departments show that such emergencies occur by the thousands every summer.

Dallas had 3,542 heat emergencies from 2009 to 2017, according to EMS data. Travis County’s EMS calls for heat emergencies increased 84% from 2010 to 2018. And the data show they hit low-income and minority neighborhoods hardest.

Joe Adkins, 81, sits on his porch in the South Oak Cliff neighborhood of Dallas on a 104 degree August day. Adkins, who has lived in the home for 40 years, spends his summer days reading the newspaper on his front porch in an attempt to keep his electricity bill at affordable levels. “It’s cool in the shade,” he said. He goes back inside in the evenings to watch Walker, Texas Ranger. Jay Janner | American-Statesman

Most Texas hospitals and public health agencies say they don’t ask whether energy insecurity played a role in the heat-related emergencies they see, which several cities have only recently begun tracking.

The Texas Department of Public Safety and the federal government expect heat-related deaths and emergencies to increase in the state in coming years.

Other southern border states have taken steps to ameliorate the effects of rising temperatures and disconnections. After California regulators learned electricity and gas disconnections had risen more than 50% between 2010 and 2017, they ordered utilities to reduce shutoffs and prohibited disconnections for Californians over 65.

This summer, Arizona instituted a moratorium against summertime disconnections after learning of the deaths of residents whose power had been cut.

But in Texas, lawmakers have largely refused to acknowledge the reality of rising heat, failing to even hold hearings on climate-related proposals during the 2019 legislative session. Lawmakers don’t know, nor have they inquired about, how many people are experiencing disconnections, much less how many are falling ill and dying as a result.

A spokesman for Dallas Mayor Eric Johnson urged lawmakers to take action. “The mayor is deeply troubled by these findings. He encourages the Legislature to take a hard look at the issue.”

Diana Hernandez, a Columbia University professor who is one of the few studying the nexus of utility policies and heat deaths and illnesses, said more needs to be done.

“I still don’t understand why this is hidden in plain sight essentially,” she said. “People are dying and at the least suffering.”

Dan Keemahill contributed data analysis to this story

In 2002, the Legislature deregulated the electricity market in most of Texas, allowing about two-thirds of Texas households to choose their power provider.

As part of a nationwide trend toward deregulation of utilities and telecommunications, conservative lawmakers in Texas and energy companies, including Enron, pushed for the move. They argued that a competitive market would lead to cheaper and more efficient electricity production and delivery. Opponents warned of price increases and the loss of consumer protections.

In the nearly two decades since, scores of private electricity retailers have entered the market, vying for residents’ business in places such as Houston, Dallas, Fort Worth, Abilene, Waco, Alice, Laredo, Round Rock and other communities surrounding Austin. The Texas Public Utility Commission oversees the competitive marketplace, and rule-making fights frequently pit private companies against consumer advocates.

Cities such as Austin, San Antonio and Lubbock retained their municipally owned energy companies, which have monopolies in most of their service areas.

Some rural areas, such as the Hill Country and parts of the Panhandle, are served by the state’s 75 electric cooperatives, which self-regulate their distribution systems.

In the years after deregulation, prices rose in the competitive marketplace compared with the rest of the state. The Texas Coalition for Affordable Power estimates that Texans in the deregulated market paid nearly $25 billion more for their electricity than fellow Texans served by municipal or cooperative utilities from 2002 to 2014. In recent years, as the price of natural gas has fallen, prices in the deregulated market have fallen below the U.S. average and are now close to prices in the noncompetitive Texas market.

Disconnection rates are also far higher in the deregulated marketplace compared with municipal electric utilities. (Cooperatives are not bound by the Texas Public Information Act, and Gatehouse Media was unable to obtain disconnection numbers.)

According to Public Utility Commission officials and experts, the disparity can be explained, in part, by the structure of the competitive marketplace. Municipal systems don’t face the same profit or competitive pressures as private companies, so they can absorb unpaid bills when setting new rates and provide customers extended deferred payment plans. Private companies are under competitive pressure to keep prices as low as possible to attract customers. They cannot as easily absorb unpaid debt and are more likely to use disconnections as a way to limit debt, experts say.

Barry Smitherman, who was chairman of the Public Utility Commission, which regulates electricity providers in Texas, left the board in 2011. In 2017, he joined the board of energy giant NRG, an appointment some investors challenged because some of Smitherman’s social media posts appeared to question the validity of global warming. Smitherman, who also had served on the Texas Railroad Commission, which regulates oil and gas interests, retired from the NRG board in 2018.

Other former commissioners have also gone to work for the energy industry. Julie Caruthers Parsley, a commissioner from 2002 to 2008, is CEO of the Pedernales Electric Cooperative. Paul Hudson, who served from 2003 to 2008, is president of General Infrastructure LLC, a subsidiary of an investment firm that has bought and sold debt belonging to deregulated electricity providers.