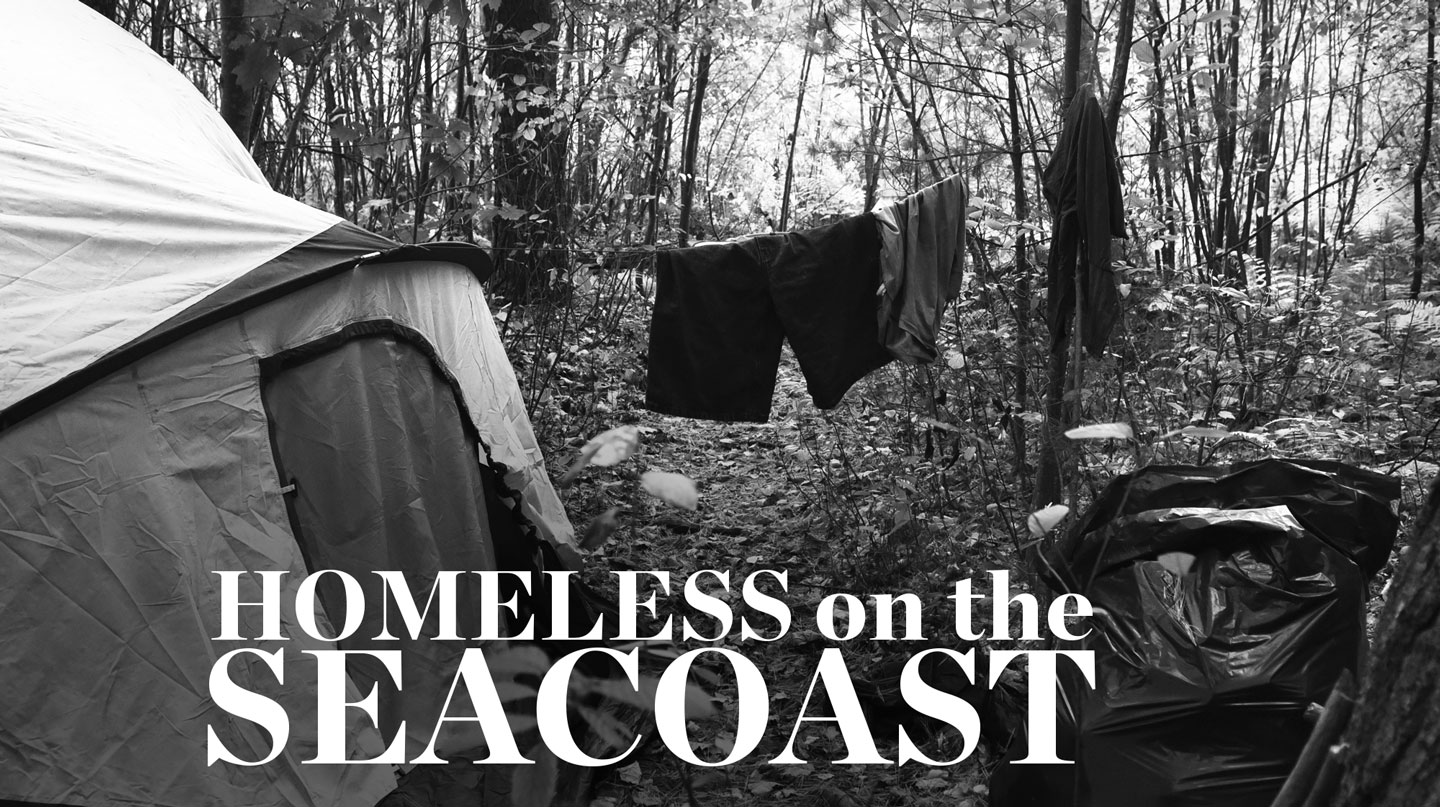

Editor's note: Homelessness is straining the Seacoast's already overburdened resources. There is no one "type" of homelessness. Over the past several months, Seacoast Media Group has spent time with families sleeping in vans, struggling single parents, youth, people tenting in the woods and others to learn about the challenges they're facing, as well the agencies and individuals trying to assist them. Here are their stories, which we hope will give a human perspective to this issue.

Part one

'At a dead end'

Tenters say public's complaints make life harder

Police, shelters, advocates and organizations across the Seacoast say 2017 has seen an uptick in the frequency of community members requesting the removal of homeless people.

Those closest to the issue say it has created an environment in which tenters and couch surfers feel less than human. That's tough, they say, because these people already feel misunderstood and pushed to the fringes.

“Just because some homeowners down the way didn’t want us (near them), they call to complain to the police department,” said Earl Lee Shaffer, a Rochester tenter who feels people are trying to push the homeless out of the city’s woods entirely. “I know eight to a dozen people who are homeless in this town who get completely pushed around. They feel like they’re at a dead end. They feel like there’s nothing they can do … but these are good people.”

Police officials say it’s difficult to quantify the increase in reports involving homelessness across the Seacoast, as individual officers and departments categorize those instances in different ways. Homeless data is also problematic at the state level, according to organizations like Portsmouth’s Cross Roads House and the Community Action Partnership of Strafford County.

In its 2016 report, the New Hampshire Coalition to End Homelessness stated the total number of homeless people in the state, based on the results of the annual HUD-mandated Point-in-Time count of shelters and wooded areas, dropped every year from 2012 to 2016. That includes a dip from 1,632 in 2015 to 1,317 in 2016, a one-year decrease of 19.5 percent. During that same period, Rockingham County decreased from 187 to 137 individuals (18.5 percent) and Strafford County decreased from 76 to 66 (10.8 percent), according to the coalition.

However, shelters and front-line case managers say those numbers don’t tell the whole story because of the way they're compiled every year. For instance, those numbers don’t include the 3,350 homeless students the state Department of Education reported in the 2015-16 school year alone. Individuals like CAP Outreach Specialist Alix Campbell say they also have a variety of their own statistics — from shelter stay lengths to rental data — that indicate homelessness may be a worse and more visible issue in communities than ever.

Rochester is at the forefront of the increase in homelessness, numerous local advocates say, and it also happens to be one of the communities in which officials have anecdotally reported the most pronounced increase in the frequency of reports to police.

Campbell said that may have something to do with the fact the city is “sandwiched” on one side by exploding housing markets pricing people out of Portsmouth and Dover, and on the other side by smaller northern Strafford County towns with limited funding and services to help those in need.

“I feel bad for Rochester because it’s getting it from all angles at this point,” Campbell said. “I feel like we’ve got a lot of people out on the street in Rochester, and I feel we’ve just barely scratched the surface on (fully identifying and assisting) that population.”

In terms of how authorities respond to citizens’ reports involving tenters and other transient individuals, Portsmouth was the only police department that told Seacoast Media Group it takes active measures to break up encampments. Others, like Dover, Rochester and Somersworth, reported they don’t move anyone along unless they receive a call from the person who owns the property or someone who has a legal basis to make such a request.

Many times callers don’t have that legal standing and when that's the case officers don’t take action, according to Rochester Police Chief Paul Toussaint.

“There seems to be a segment of the community that strongly believes that we as a police department are hunting these homeless camps and moving them out and displacing them and that’s what we do,” said Toussaint, echoing statements provided by Dover, Somersworth and other departments. “That’s not. If we don’t get a complaint, we don’t deal with these encampments, but when we do we have to. We deal with any violations of law that we have to, but we also have to keep in mind they’re human beings and that there’s a human side to this whole thing.”

Portsmouth Police Lt. Michael Maloney said he wouldn’t describe his department’s actions as hunting homeless camps, but added directed patrols occur “often” to ensure individuals aren’t tenting on certain city-owned parcels and at a few known campsites. He said the patrols began as the result of some “pretty significant” trash and waste issues in areas he declined to disclose.

However, just because Port City cops make targeted patrols doesn’t mean they’re out to get homeless individuals, according to Maloney. He said a major focus of the department’s active measures are built around the idea of providing outreach.

“We have to treat them with respect and compassion and help them with any assistance they may need, and at the same time if they need to be held accountable, they need (to),” said Maloney, who stressed the majority of his department’s interactions with homeless individuals come from citizen reports.

Tenters in Dover, Portsmouth, Rochester and Somersworth described instances in which they encountered hostile treatment from police. Seacoast Media Group wasn’t able to confirm or disprove those claims.

“They’ve got nothing better they can do?” said Danny, a Portsmouth tenter who has been without a home on and off his entire life. Danny asked Seacoast Media Group not to use his last name out of fear of retribution. “We ain’t bothering or hurting nobody. All we’re trying to do is make a living and people are discriminating. We’re not bothering anybody. Lay off the people who are just trying to survive.”

Monica Nagle is a Dover artist, poet and peace advocate. Her time with tenters along Portsmouth’s railroad inspired her to publish a book of firsthand stories, lyrics and other artwork called, “The Tracks,” which aims to raise awareness of homeless-related issues and the individuality of homeless people.

Nagle said too often, she’s found community members deem the homeless to be a drain on society, unworthy of assistance, particularly if they seemingly don’t want help or have multiple relapses into homeless situations.

In the recovery and mental health communities, advocates preach the need to continue to provide assistance and options for individuals even if they refuse treatment for their disorders. The idea is that if you increase the safety and overall dignity offered to people, the better chance you have of keeping them alive and healthy to the point they have the ability to pursue help. Nagle believes the community should adopt a similar stigma-free mindset in regard to homelessness.

“They are our community members,” Nagle said. “We have to consider that just because (people) don’t want to see someone panhandling or in a tent somewhere … that doesn’t mean they’re not worthy of help.”

Todd Marsh, Rochester’s welfare director and someone who has worked in multiple area shelters, agreed. “People view it as they’re making a choice, but they’re making that choice based on challenged decision making,” he said.

Toussaint stressed all community members, not just people who identify as homeless, should understand property owners shouldn’t be vilified for not wanting unauthorized people on their land.

“It’s not unreasonable for a property owner to say they don’t want someone on their property,” he said. “They’re well within their rights to say (that).”

Maloney acknowledged the reality of most departments’ homeless efforts are cyclical. Shelters are overburdened and limited affordable housing is available on the Seacoast, which he said means officers are often moving the same individuals from location to location or organization to organization within a community or multiple communities.

Welfare departments and social service agencies reported feeling like they were a part of similar cycles, and Campbell said these can create “compassion fatigue” that impacts the work of even the most helpful individuals. Many officials said that’s precisely why prevention and outreach are so important when they are called out to a specific site, as those are often the best times to offer help.

“The fact of the matter is we deal with (a lot of) the same people on a consistent basis,” Maloney said. “It really falls on the individual to (buck the cycle) and pursue resources they may or may not choose for themselves. We can’t enforce our way out of it by arresting them … but we can assist them.”

Read part two of Homeless on the Seacoast:

'Housing is nonexistent'

Low-income people left out in 'landlord's market'

Homeless on the Seacoast: the faces

They are single mothers, middle-aged men, teenagers, adults who were abandoned as kids, some have been in trouble with the law, many have not. They opened up their lives to a reporter and photographer so we can better understand the people who live here but often are invisible in our local community.