High-stakes challenges for R.I. education

First in a year-long series on education

THE LANGUAGE DIVIDE

English-language learners are the fastest-growing population in Rhode Island’s schools, yet the state and the schools are failing these students.

They are failing them by not setting aside enough money, by not teaching English learners in dual-language programs, and by treating these students as a problem to be fixed instead of a valuable asset worth investing in, according to advocates, education leaders and the Department of Justice.

English-language learners are defined as students who require assistance with language acquisition, according to the Rhode Island Department of Education. Many are immigrants, but more than 40 percent of English-language learners in Rhode Island were born in the U.S.

“We’ve dropped the ball for decades,” said Marcela Betancur, executive director of the Latino Policy Institute at Roger Williams University. “Before we had a funding formula, we never included this population. It wasn’t taken into consideration that this population required a different attention and had different needs.”

“We don’t look at education as an investment,” she said. “That’s one of our biggest faults.”

Fifteen years ago, there were about 10,000 students in Rhode Island schools who were classified as learning English. Today, there are more than 15,000 out of a total student population of 142,481.

A third of Providence’s students are English-language learners, and that number has doubled in seven years. And it’s not just Latino students. More than 54 languages are spoken in the city’s schools.

This is no longer a primarily urban phenomenon. Students who are new to English are also moving to the suburbs, to Cranston and Johnston, Cumberland and South Kingstown.

“You ignore the English-language learner population at your own peril,” said state education Commissioner Ken Wagner, “because they are not only a rich source of the cultural tapestry of our state, but they’re the fastest-growing segment. They will make up a huge percentage of our workforce, and if we don’t invest in all of us, we’re shooting ourselves in the foot.”

The test results speak for themselves.

On the Rhode Island Common Assessment System, in third-grade English, only 12.9 percent of English learners meet the standard, compared with 44 percent of native English speakers.

— In third-grade math, only 13.2 percent of English learners were proficient, compared with 38.7 percent of native English speakers.

— Rhode Island students overall have an 85.1-percent graduation rate. That rate drops to 72.3 percent for students learning English.

— SAT scores are much lower for English learners, in both English and math.

A recent report by the Annie E. Casey Foundation concluded that there is a crisis for Latinos in Rhode Island. The foundation’s Race for Results report said Rhode Island’s Latino students ranked worst in the nation in terms of their chances for success.

Last May, a letter written by Gabriela Domenzain, then executive director of the Latino Policy Institute, and signed by a dozen state education leaders said the same thing.

“The Latino Policy Institute is all too familiar with the gaps that exist in educational opportunities for Latinos, having done research in this area,” Domenzain wrote in the letter. “We have all worked to bridge many of the gaps that exist for our students regarding emergent bilingual learning needs. It is time to make a large and ongoing investment in these programs sufficient to meet the need.”

This spring, after listening to their concerns, Gov. Gina Raimondo proposed increasing funding for English learners from $2.7 million to $5 million.

But funding for English learners is not embedded in the school-funding formula, which determines how much state money school districts receive, based on a district’s level of poverty and its ability to tax.

“The state has failed this population,” said Julie Nora, executive director of the International Charter School, which immerses its students in two languages, English/Spanish or English/Portuguese. “We need to do a better job of understanding who these students are, and then providing them with appropriate and robust programs.”

The population is not monolithic. Some students have just arrived here and have little formal education in their home language. Others have been here seven years and still struggle with English.

Meanwhile, last August the Providence school district agreed to a settlement with the U.S. Department of Justice to rectify widespread problems in its English-language programs, part of a broader investigation by the agency into whether big cities are adequately serving this population.

Among its findings, the Department of Justice concluded that not enough English learners were receiving instruction from certified English as a Second Language teachers, that some students weren’t getting enough ELL instruction, and that other English learners hadn’t been placed in the appropriate classes at all.

Providence Schools Supt. Christopher N. Maher said he was not surprised by the agency’s criticisms. In fact, he welcomed them.

Maher has been ringing the alarm bell about the historic underfunding of English learners since his arrival almost four years ago. At the time, Rhode Island was one of only four states that didn’t set aside money specifically for this population.

“This is a population that is expanding,” Maher said. “It will affect the entire state with a few exceptions. And we have a moral responsibility to provide all children with an adequate education.

If Rhode Island doesn’t do anything, he said, “Ten years from now, we will wind up with a population which will not be able to be successful in the workplace.”

We have all worked to bridge many of the gaps that exist for our students regarding emergent bilingual learning needs. It is time to make a large and ongoing investment in these programs sufficient to meet the need.”

Gabriela Domenzain, then executive director of the Latino Policy Institute

Dual-language instruction is the only approach that closes the achievement gap, according to one of the leading experts in the field, Virginia P. Collier, co-author of 77 articles on the topic.

“We’ve studied over 8 million student records around the country,” she said. “English learners who have an opportunity to attend school in their mother tongue and in English soar by the time they get to middle and high school.”

Yet only 1 percent of English learners are enrolled in such programs in Rhode Island, according to Erin Papa, chair of the Rhode Island Foreign Language Association.

Dual-language programs — where students spend half of their day learning in English and the other half learning in a second language — honor both cultures, that of the English learner and that of the English-speaking native, Wagner and other educators say.

Demand for dual-language instruction is strong. Papa said two students compete for every seat in a dual-language classroom. The demand, however, far outstrips the availability of such programs in Rhode Island. Dual-language immersion is offered in only eight of Rhode Island’s 306 public schools.

Rhode Island’s incoming public education commissioner, Angelica Infante-Green, is both bilingual and the daughter of immigrants from the Dominican Republic. Her two children speak Spanish and English at home.

As someone who championed the rights of English learners in New York, she is uniquely positioned to shine a light on this population in Rhode Island.

“Dual language is the way to go for Rhode Island,” Infante-Green said. “It breaks down a lot of barriers — the idea that dual language is for them, not us. It’s a place where everyone thrives. It’s very inclusive. It opens up the world for all of our kids.”

“Right now, we can’t imagine a world where English-language acquisition, Spanish-language acquisition, Mandarin acquisition, is valued, prioritized and taken seriously,” Wagner said. “We also can’t imagine that kids who have different learning needs … can hit the same high standards that everyone else has hit.”

“The beautiful thing about it is, it actually doesn’t require any additional money, because the way the dual-language model works is you teach the content areas in one language in the morning, and then you teach the other content areas in another language, let’s say Spanish, in the afternoon,” Wagner said. “You’re still teaching the same number of courses, you’re still teaching the core content areas, you’re just teaching them in different languages.”

The seal of biliteracy, a formal recognition on a student’s transcript of proficiency in English and another language, is one way that schools are starting to appreciate multilingualism, Wagner said. The seal of biliteracy, created by legislation passed in 2016, will be available in all school districts by 2021, but some, including Coventry, Pawtucket and Cumberland, have already started offering it.

“We built that not only into our graduation structure so kids can be recognized on their diploma and their transcript for the seal of bi-literacy, but it’s also built into our accountability system, so schools and districts get credit and have incentive to increase the percent of students who earn the seal of bi-literacy,” Wagner said.

Rhode Island also has a teacher pipeline problem.

Historically, the state’s teacher preparation programs have graduated a plethora of elementary-education teachers when what the state really needs is special-education teachers, high school math and science teachers, and teachers of English as a Second Language.

Wagner said schools of education are largely driven by what the tenured faculty wants to teach. That, in turn, influences what students choose as their majors, which generates tuition dollars.

At a recent meeting, Wagner said he was shocked that a higher-education department chair had no idea that Rhode Island has too many elementary-education teachers.

“My only response was, where have you been for the past 40 years?” Wagner said. “We know that 26 percent of our emergency [teacher] certifications are for English-language learners.”

Rhode Island’s colleges of education have to pivot — and quickly — so that teacher supply matches demand.

Rhode Island College, the state’s largest producer of teachers, is doing just that.

President Frank Sanchez said the college, after lengthy conversations with local educators, heard two things: we need more special-education teachers and more English as a Second Language (ESL) teachers.

The college decided to follow Massachusetts’ lead.

Starting next fall, every aspiring teacher will take a foundation course that teaches special education and ESL. Then, every one of those students will be required to take a second course in either subject.

“One hundred percent of our graduates will have the skills to support English-language learners,” Sanchez said. “The genius of this approach is it will be baked into the existing four-year degree. Chris Maher needs 1,000 ESL teachers today. We can never support Providence unless we redesign the entire pipeline, and that’s what we’re doing.”

But what about the immediate demand for these teachers? RIC is working on short-term needs, too.

The college is offering teachers in Providence, Woonsocket, Cumberland and Johnston an opportunity to get their ESL certification on an accelerated timeline. RIC offers the classes in schools where the teachers work, and it provides a tuition discount.

“Massachusetts said we have to level the playing field between the rich and poor,” Sanchez said. “What they did was stay the course, year after year. … Our graduates have to be as effective in a rural setting as they are in a suburban or an urban one. These are the essential skills they have to have.”

Raimondo seeks to boost spending for English-language learners

Proposes $5M line item, but advocates prefer funding that’s ‘baked into’ education budget

How much does it cost to educate an English-language learner?

More than what Rhode Island is spending, advocates say.

This year, Gov. Gina Raimondo has proposed tacking $5 million for these students onto the state’s education budget, but some want to see a change not only in how much funding is directed toward English-language learners, but also in how the money appears in the state’s education budget.

Rhode Island has included funding specifically for English-language learners since Fiscal Year 2017, when the General Assembly approved $2.5 million for the demographic on a pilot basis, said Kevin Gallagher, Raimondo’s deputy chief of staff.

The following year, Raimondo proposed making the funding a permanent feature of the state’s education budget, and in Fiscal Year 2019, the amount dedicated to English-language learners increased to $2.75 million.

Gallagher said funding English-language learners as a line item in the budget means the state can more easily ensure that the money is being used specifically for teaching English as a Second Language. But some advocates say tacking the money on this way makes it more susceptible to cuts by legislators.

Stephanie Gonzalez, co-founder of Parents Leading for Educational Equality, a parent-led grassroots organization advocating for underserved students, said she would like to see funding for English-language learners calculated on a per-pupil basis and distributed with the rest of the state’s education budget.

“Because it’s not baked into the per-pupil bucket, it’s not predictable, and so districts can’t actually use that money as effectively as they’d like to,” she said.

Because of the way this funding is decided, school districts can’t plan on a set amount ahead of time, said Providence Public Schools spokeswoman Laura Hart.

In Fiscal Year 2018, the Providence Public School District received just over $1.5 million in funding for English-language learners. That money all went toward salaries and benefits for teachers of English as a Second Language, according to Hart.

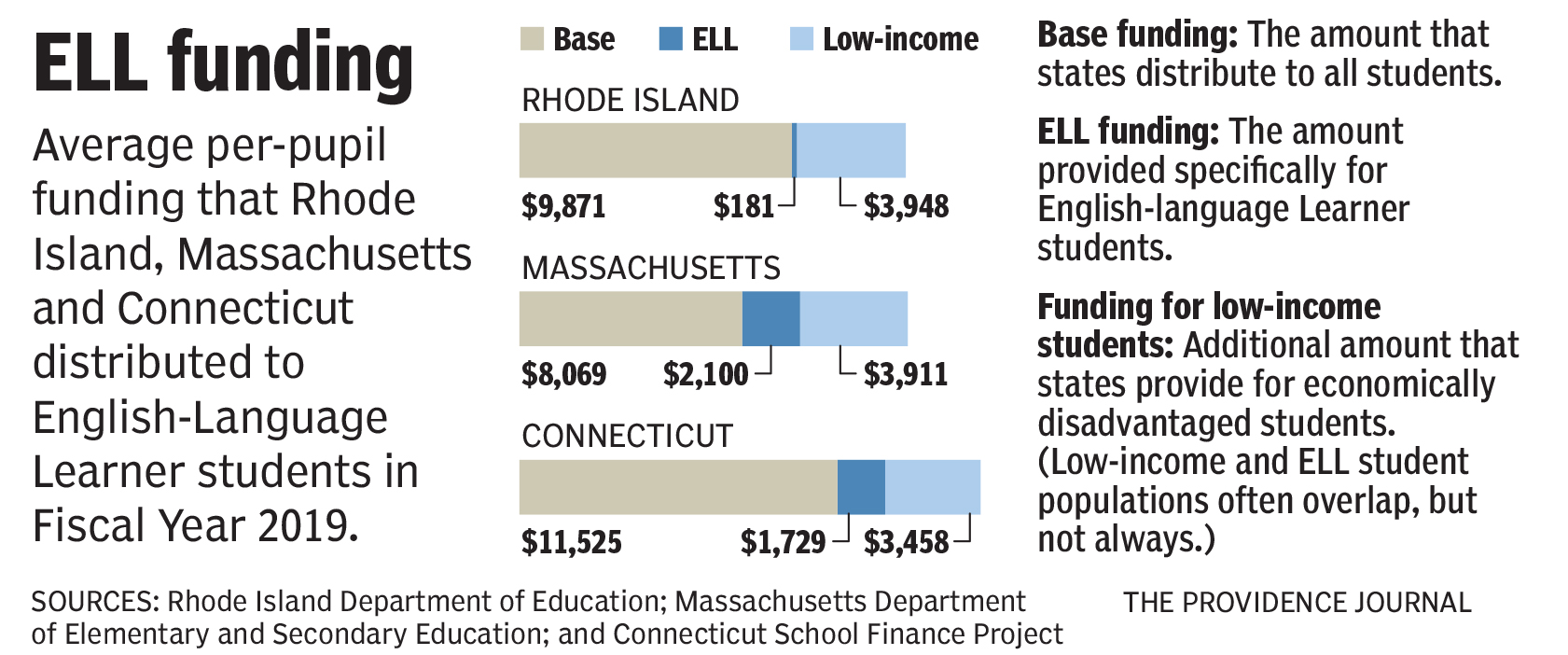

In Massachusetts, Gov. Charlie Baker has proposed increasing the state’s funding for English-language learners. Under Baker’s proposal, each ELL student in Massachusetts would be funded, on average, $2,490 over the base per-pupil expenditure — up from $2,100 in the current year — according to Jacqueline Reis, spokeswoman for the Massachusetts Department of Education.

In Connecticut, English-language learners receive an additional $1,728 above base funding, according to Katie Roy, executive director and founder of the Connecticut School Finance Project.

Connecticut also provides an additional $2 million a year for English-language learners as a line item. A school must have at least 20 English learners who speak the same language to be eligible for a share of this money.

If the Rhode Island General Assembly approves Raimondo’s proposed $5 million for English-language learners, that would give each ELL student an extra $329 above the base funding. Currently, ELL students receive about $181 above base funding.

Each of these states also provides additional funding for students in poverty. Education officials say the populations of English-language learners and students who receive free or reduced lunch often overlap. Many advocates, though, say that it’s important for states to provide separate funding streams that target ELL students because they have specific learning needs, and not all ELL students come from low-income families.

In Rhode Island, about 82 percent of English-language learners receive free or reduced lunch, meaning they are eligible for additional funding for economically disadvantaged students.

Gallagher said it’s difficult to compare education funding between tates because each state has a different funding formula, but there’s no doubt that more money needs to be dedicated to Rhode Island’s English-language learners. Gallagher also noted that the governor has proposed about a $30-million increase in state aid for all K-12 students.

“I believe that more resources are needed, and so does the governor,” he said. “But I would say that more money isn't the only thing that we need to do to help improve our schools so they’re performing at the same level as those in Massachusetts.”

Gallagher said Rhode Island also needs to continue assessing students using the standardized test RICAS, which mirrors the MCAS in Massachusetts, as well as ensuring that all schools are using high-quality curricula and teachers have access to professional development.

Adequately funding English-language learners isn’t only an issue for urban areas of Rhode Island, where the largest ELL populations are concentrated; it affects the entire state, said Marcela Betancur, director of the Latino Policy Institute at Roger Williams University, who said she would like to see Rhode Island funding ELL students at the same level as Massachusetts.

“When we have an educated population, it’s an economic driver for the future,” she said. “We are more likely to have individuals who have different job skills and job attainment. It's a long-term investment.”

South Kingstown is suburban pioneer in dual-language instruction

The district is breaking down barriers for students and streamlining certification for teachers

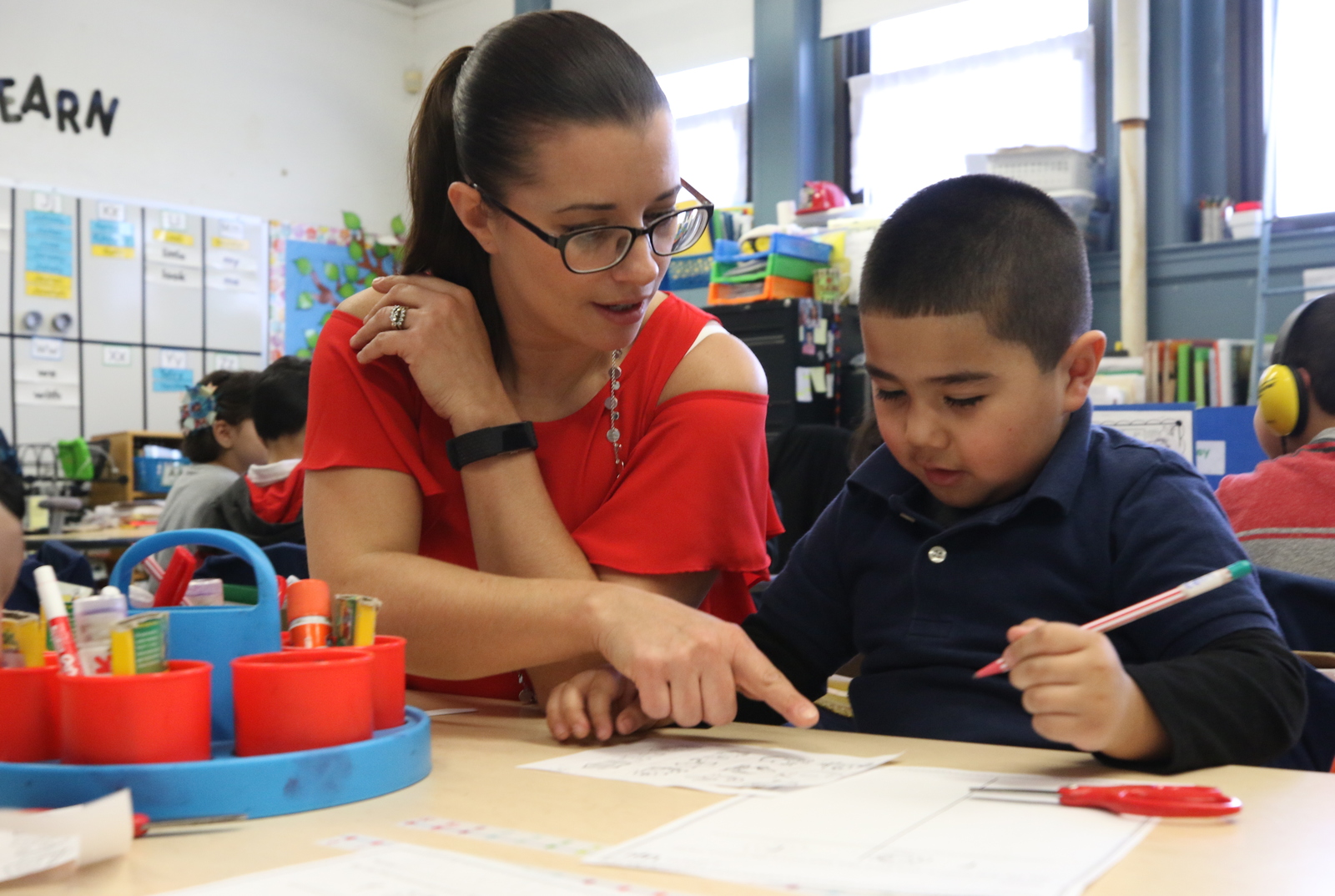

SOUTH KINGSTOWN — Historically, schools have seen English-language learners as having a problem that needs fixing. But that narrative is starting to change, and South Kingstown is leading the way.

In West Kingston and Peace Dale elementary schools, students — most of them native English speakers — are immersed in dual-language instruction, learning in English for half the school day and in Spanish during the other half.

A total of 350 students in kindergarten through third grade are enrolled in dual-language classes. They are selected by a blind lottery, and there is a waiting list (20 last year) to get in.

South Kingstown is seeing an uptick in English-language learners — as are Warwick, Cranston, North Providence and Johnston — though the phenomenon is more commonly associated with urban school districts.

In 2011-2012, South Kingstown only had 22 English-language learners. Now it has 59, according to state data. Last year, it peaked at 72.

Fifteen languages are spoken in South Kingstown. The most common are Spanish, Arabic and Chinese, the last two spoken by the children of University of Rhode Island faculty.

South Kingstown is the first suburban community in Rhode Island to offer dual-language classes, not simply in response to its growing English-learner population but because biliteracy benefits all children, no matter their native tongue, educators say.

“The positive impact on these dual-language learners is incredible,” said Lindy Fregeolle, the district’s dual-language program coordinator. “When you go into a classroom and see 23 students, 20 of them learning Spanish, and you see someone 6 years old who speaks Spanish helping their peers learn another language, that child has such a sense of pride. That child is using his culture to help others.”

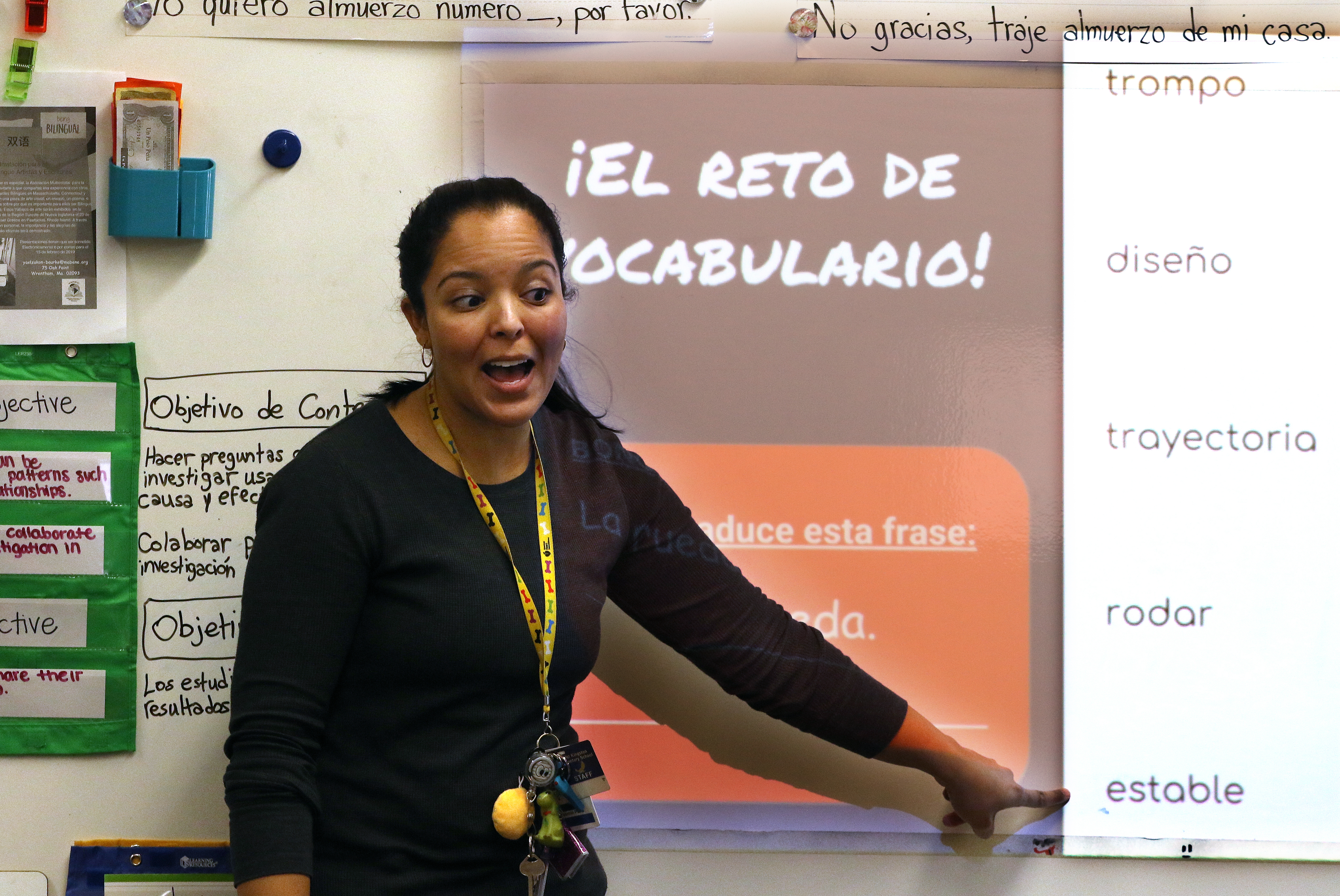

In a recent visit to a dual-immersion class in West Kingston Elementary School, the English and the Spanish teachers taught a third-grade class together. Students, switching from one language to another, searched for the English equivalent of certain Spanish vocabulary words.

“What is the English word for estable?” teacher Stephanie Balasco asked.

Several hands shot up. The energy in the room was palpable with lots of excited chatter among the children.

“Stable,” a student shouted.

“What strategy did you use there? Was it a cognate?”

Cognates are words that sound similar in two different languages, like “pattern” and “patron.”

The instruction switches seamlessly from one language to another. At one point, a child whispers advice to another student struggling with the Spanish equivalent.

“What is the Spanish verb for ‘to roll?” Balasco asked.

“Rodar!” said a child.

Two challenges — cost and time — discourage regular classroom teachers from pursuing certification in English as a Second Language, which typically requires two years of training.

That’s why South Kingstown, in 2015, decided to “grow its own.”

Working in partnership with Rhode Island College, the district offered English as a Second Language classes at the West Bay Collaborative, in Warwick, a closer location than RIC. The district pays 85 percent of the tuition; the teacher pays the rest.

“This is a priority for us,” Fregeolle said. “Teachers need this training” to have the skills necessary to teach English learners in mainstream education classes.

Historically, English learners were pulled out of class to get intensive language instruction.

Now that South Kingstown has 21 classroom teachers who are ESL certified, those students can remain in their math and science classes.

Meanwhile, the R.I. Department of Education is offering a fast track to train more ESL teachers by allowing education teachers to earn an endorsement instead of a full certification. Endorsement is a way for teachers to get additional training without going for a more time-intensive certificate.

The University of Rhode Island, in 2016, began offering a master’s degree in English as a Second Language and bilingual and dual-language immersion. Eighty-five people have completed the program or are in the process of doing so.

URI’s School of Education has partnered with five urban districts with the largest populations of English learners. URI is offering the 10-course master’s program at a reduced cost, a savings of $800 per class.

Roger Williams University is offering Providence teachers a fast-track program that will take only one year to complete instead of two and costs much less, with the school reimbursing $500 in tuition. It combines online training with classroom experience.

“Our biggest challenge,” Wagner said, “is breaking that lack of imagination about what kids can do if we prioritize language acquisition, if we believe in all of our kids, if we collectively say this is a priority.”

The positive impact on these dual-language learners is incredible. When you go into a classroom and see 23 students, 20 of them learning Spanish, and you see someone 6 years old who speaks Spanish helping their peers learn another language, that child has such a sense of pride. That child is using his culture to help others.”

Lindy Fregeolle, the district’s dual-language program coordinator

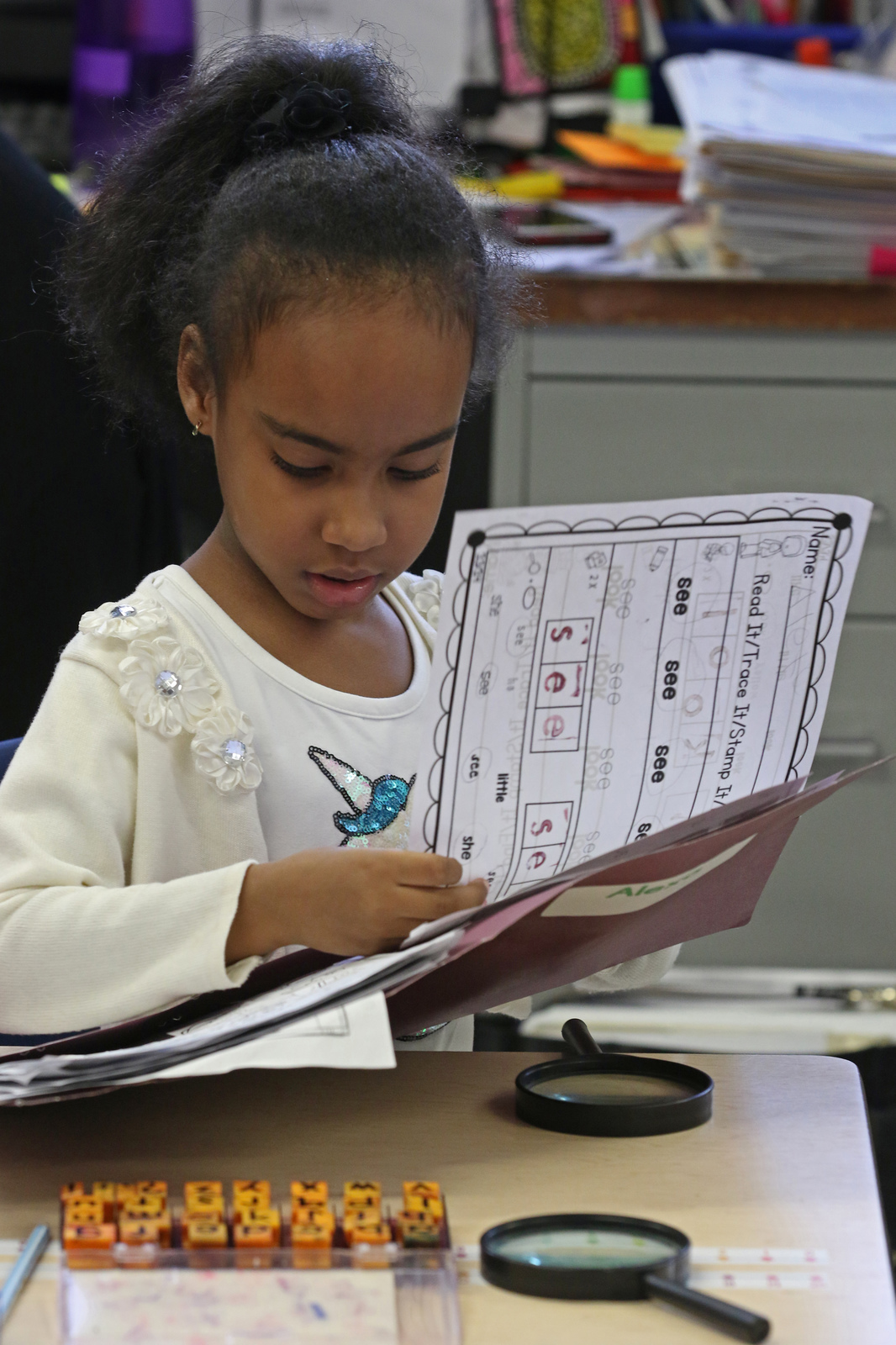

Two languages, one goal in Providence elementary school

Bilingual mastery starts in kindergarten at Providence’s Spaziano Elementary

PROVIDENCE — On a recent morning at Frank D. Spaziano Elementary School, around 20 kindergarteners sat in tiny chairs — some drawing, some writing, some plugged into iPads — while their teacher, Esperanza Vallejo, checked in at each of their tables.

Across the hall, another classroom full of kindergartners was working on similar activities while their teacher, Joana Santos, made her rounds.

The two classrooms mirrored each other except for one key difference.

Vallejo spoke in Spanish, while Santos taught in English.

The Spanish-English education is part of a dual-language program at Spaziano that has been in place since 2017 and is expanding every year.

After lunch, the children who started their day in the English classroom moved to the Spanish classroom and vice versa.

“They become biliterate,” said Santos, who has been teaching kindergarten on the English side for nearly two years. “They learn how to read and write in both languages, and I think that’s extremely important. Not every child’s able to do that or has that opportunity.”

There are at least nine schools in the state that offer dual-language programs. Schools do not need to seek approval from the Rhode Island Department of Education before beginning a dual-language program, so there could be others in their early stages, according to Megan Geoghegan, spokeswoman for the department.

Three of those schools fall within the Providence Public School District, and Superintendent Christopher Maher said he is seeking to expand to a fourth next year.

State education Commissioner Ken Wagner said dual-language programs are effective in teaching English to native speakers of other languages as well as in helping English speakers to acquire a second language.

“That really is the best practice model,” he said. “... I don’t care if it’s second-language acquisition where the kids are acquiring English as a second language, or the students are acquiring Portuguese, Spanish, Mandarin, whatever it is, the right model is the dual-language immersion model, and the right way to do it is to start as early as you can, ideally by kindergarten.”

Currently, dual-language programs in Rhode Island are concentrated at the elementary level, except for the French-American School of Rhode Island, a private school in Providence that offers English, French and some Spanish instruction through the eighth grade. Most dual-language programs consist of English-Spanish instruction, except for the French-American School and the International Charter School in Pawtucket, which offers two tracks: English-Spanish and English-Portuguese.

Wagner said he would like to see the programs expand to reach more students and higher grade levels in Rhode Island.

“If I were starting a high school right now … I would do a bilingual, dual-language immersion, STEM school,” he said, using the acronym for science, technology, engineering and math. “I would teach STEM in the context of language acquisition, because STEM is the biggest thing we need to push on in our economic development work, and because dual language is the biggest thing we need to push on in every aspect of our work.”

And dual-language programs don’t require additional funding, he said, because teachers are teaching the same number of courses and the same curriculum; it’s just that half the day is taught in another language.

While dual-language programs can provide an opportunity for native English-speaking students to become fluent in another language, they can also be an important tool for those new to English.

“The beauty of the model from the student perspective is everybody gets a chance to struggle,” Wagner said. “The kids who are native English struggle in the afternoon in Spanish. The kids who are native Spanish struggle in the morning in English. Everybody gets an opportunity to be an expert.”

But dual-language isn’t the answer for every English-language learner, Maher said. The program works best when students start in kindergarten and move up through the elementary grades, which is why schools that incorporate dual-language programs start with a kindergarten class and expand up one grade each year. (For example, Spaziano started its dual-language kindergarten program two years ago, expanded to first grade the following year and will bring the program to second grade classrooms next year.)

About 45 percent of English-language learners in the Providence Public School District are born in the United States, meaning they have the opportunity to start in kindergarten because they’re already here.

“This is a great way to serve them,” Maher said.

But this type of program is not a good fit for an English-language learner who arrives in the school district at an older age or speaks a language other than the one offered in the program. That is why other forms of English as a Second Language instruction will always be necessary, Maher said.

“It’s not just a one-size-fits-all approach, because the needs of English-language learners are very diverse,” he said.

In the dual-language kindergarten classrooms at Spaziano, most of the students are native Spanish speakers, like Kristopher Santo-Barahona, a 5-year-old student from Guatemala who sat in class on a February morning cutting out pictures of English words that start with the letter “F.”

Alexa Cabral, a 6-year-old student from Providence, said she speaks English at home with her family but liked her Spanish class at school best.

Her favorite Spanish word? “Familia,” she said.

“Most of the kids develop pretty well,” Santos said. “They’re able to distinguish the languages. They know exactly when they should be using the English, they know when they should be using the Spanish.”

Wagner said adults who can speak more than one language have an undeniable advantage in the workforce, but in order to get there, they need to start learning as children.

“Everyone who is acquiring a second language, whether that second language is English or something else, they’ve got the leg up in the 21st century, full stop,” he said. “The challenge is helping families, elected officials, district leaders to realize that if we don’t invest in language, we’re not investing in our future.”

Dominican native’s drive triumphed over language barriers

Years feeling like an outsider in ESL classes sharpened her ambition, and her motivation to help others

PROVIDENCE — Ashley Rodriguez Lantigua speaks confidently as she describes her goals, her passions and the people she wants to help.

“I definitely want to go to a four-year college, and I think I want to do graduate school,” the 17-year-old Classical High School senior said during a recent interview at The Providence Journal. “I hope to help students that are international students. … I’ll be able to guide them with resources and … help them figure out a way to get through this.”

Rodriguez Lantigua knows she can help these students because she came to this country herself as a 10-year-old from the Dominican Republic and had to navigate a new country and school system without speaking the language.

“It was so cold, and the trees didn’t have leaves, like I had never seen that, so it was just so weird,” she said. “My English level was at zero.”

It was a big change for Rodriguez Lantigua — a self-described “isleña,” or islander — who grew up walking to school and playing outside with friends and neighbors.

“It was completely different, and at first it was sad,” she said. “I feel like adjusting was really hard.”

But Rodriguez Lantigua said she never lost sight of the reason why she came to this country: to get the best education possible.

“My mom never got the chance to attain an education because she was so poor,” she said. “... She always wanted me to hold on to education because she knew that’s how you can make it far.”

Once she entered DelSesto Middle School, though, and was placed in an English as a Second Language, or ESL, program, Rodriguez Lantigua said she realized that much of her learning had to be self-driven.

She said the students in ESL classes were separated from other students in the school and looked at differently. She felt the curriculum didn’t accommodate students with more advanced levels of English, and that all the students ended up being left behind and unable to engage in the same activities that others students in school were participating in.

“We were looked at as the loud people and the people who were like intellectually behind,” she said.

“While the other kids were engaging in plays and while they were reading in their English classes, we were doing the same [things], practicing words and stuff,” she said. “Which ... it was important, and we needed that, but we also needed to engage. We needed to do more ... literature. We needed to do more engaging work and activities that helped us with our public speaking.”

But Rodriguez Lantigua remained focused. She used a board and markers at home to learn new English words every day. Her mom, too, was a constant source of inspiration.

“When she came here, it was a big transition for her, too,” Rodriguez Lantigua said. “She had to go from a stay-at-home mom to a low-income worker here, and she didn’t know the language, either. … So seeing her struggle and seeing that she trusted that being here was going to be better for us, I trusted that hope in her, too.”

By the time she was finishing middle school, Rodriguez Lantigua said she was determined to get into Classical High School, a rigorous college-prep school where she didn’t see many of her ESL peers going.

Only about 20 percent of Classical’s currently enrolled students were considered English-language learners at some point in their K-12 schooling, according to Providence Public Schools spokeswoman Laura Hart.

Rodriguez Lantigua said she didn’t pass the entrance exam to get into Classical. She went through an appeal process and sent letters of recommendation from her teachers, but still wasn’t admitted.

At the end of the summer, though, Rodriguez Lantigua said she got a call from the principal, who said he was willing to give her a spot.

“Ashley is a real asset to Classical High School,” Principal Scott Barr wrote in an email. “A strong student and a hard worker, she has been a leader and an advocate in the school; from student activities to student government — roles she manages with grace and humility.”

At Classical, Rodriguez Lantigua said she finally realized how much her education had differed from that of her peers.

“The kids had completely different skill sets than I did,” she said. “I remember being able to translate really well, because that’s what I always did … but when it came to math or when it came to … reading comprehension, I always felt like I was falling behind.”

Determined to keep up her education, she worked hard and continued her involvement with community groups such as Youth in Action, a Providence-based afterschool organization for high school-age youths. Last summer, she interned in Gov. Gina Raimondo’s office and recently found out that she has been accepted at two of her top-choice colleges: Brandeis University and the College of the Holy Cross.

Rodriguez Lantigua said she’s come to see her former status as an ESL student as a benefit rather than a shortcoming.

“Before,” she said, “... I felt like it was a bad thing to be learning English. ... I felt like I was falling behind, so I felt at a disadvantage because of that.”

“But in reality, now, when I think about it, I can engage with newcomers, I can engage with even adults who didn’t get the chance to learn English,” she said. “I appreciate it a lot more now, and I know that it is hard for those students who are in the ESL programs right now to look at it like that, because they’re consistently being told that they are falling behind or that they’re at a disadvantage because they can’t be engaging in those activities … I feel like people should definitely look at it as a more positive skill.”

Refugee turns role model, with some helping hands

Learning English opened up a world of opportunities to Night Jean Muhingabo after early setbacks

Night Jean Muhingabo is an example of what happens when a strong will meets nearly insurmountable odds.

Born and raised in a refugee camp in the Republic of Congo, Muhingabo arrived in the United States with his mother and younger sister. He was 16, and spoke French but no English.

“To me, the dream was really to help my family get out of the camp,” said Muhingabo, who is now a student at Rhode Island College. “We always heard, ‘When you get to the U.S., there is free college, free health care.’ Even if I finish university in my country, there is no job for you.”

But fitting into an American high school — Central High in Providence — was daunting. Surrounded by a swirl of languages he didn’t understand, Muhingabo had to navigate the opaque intricacies posed by social media, the rush of a high school schedule, and loneliness that comes with being an outsider.

“I couldn’t speak English. I was really shy,” he said. “Some students attacked me in the park. I didn’t go to school for a week.”

Muhingabo was so stressed out that his doctor sent him to a therapist, who gave him the courage to return to school.

But he was fortunate. He had Brandy Moore.

Moore stayed after school to help him learn English. She also invited him to join the Dream Refugee Center, where Muhingabo could share his frustration with other refugees facing the same challenges.

“Knight showed a great deal of resiliency,” said Moore, who teaches introduction to literature to newcomers. He absorbed the language like a sponge.”

She said what helped Muhingabo become fluent so quickly was his high degree of literacy in other languages. Muhingabo speaks five languages: two of them he learned so he could communicate with other African refugees.

In 2015, he showed a poem to his English teacher called “We Can Make This World a Better Place.” He read it, in French, at World Refugee Day. Inspired, he began reading his poems at the Refugee Center, at Brown University and at Rhode Island College.

Muhingabo began to shine. He graduated from Central High School in two years and won a full scholarship to RIC from the Rhode Island Foundation.

But his dream doesn’t end with his own success.

He volunteers at the Refugee Center, where he mentors teenagers like himself. Muhingabo was also recently selected to participate at a global peace conference in South Africa.

“My dream is to go back to the Congo, to open a school. I [also] want to make a difference in Rhode Island. My family never had a home before. We were just moving. Here, is the first time I feel safe.”

What kept him going? His mother.

Muhingabo would say, “Mom, this math is really hard.”

“She was telling me, ‘You’ve been in a refugee camp. I’m sure you can go through it. This is just another challenge.’ She kept reminding me where we came from.”

Muhingabo wants districts to help refugees learn English and get the social and emotional support they need. Providence did open a program for newcomer students with limited formal education in the spring of 2017, but it was too late for Muhingabo, who was in his last semester of high school.

“It was hard for me,” he said. “I had to keep too much stuff to myself.”

Any words of advice for newcomers like him?

“Really, just like, keep going,” he said. “Fight hard. I hope other refugees, when they see me, they can say, 'If he can do this, so can I.’”