Kristen Parisi

Kristen Parisi had never been apart from her chair until she flew to her best friend’s bridal shower

As she waited for a baggage handler to bring her wheelchair from the cargo hold to the jet bridge, Kristen Parisi felt a building dread that was confirmed when one of the JetBlue flight attendants asked, “Oh, are you waiting for something?”

“They didn’t realize they had a disabled passenger,” recalled Parisi, who was paralyzed in a car accident when she was 5. “I told them I was waiting for my wheelchair. … They’re like, ‘Sorry, there’s not a wheelchair in the plane.’ At that point, you go into crisis mode a little bit.”

A flight attendant called for a wheelchair agent to move Parisi off the plane. The chair was so large her paralyzed legs didn’t stay on the footrest, leaving her feet to drag across the ground.

After getting the attendant to stop, she sat cross-legged with her backpack in her lap. She held on tightly to the armrests so her unsupported torso would not tip over. The attendant found a smaller chair, but its foot plates were broken.

“One foot was up in the air with my ankle turned over,” she said. “At that point, I was like, this is the least of my problems. … It was heart-wrenching not knowing where my chair was. I have never been apart from it.”

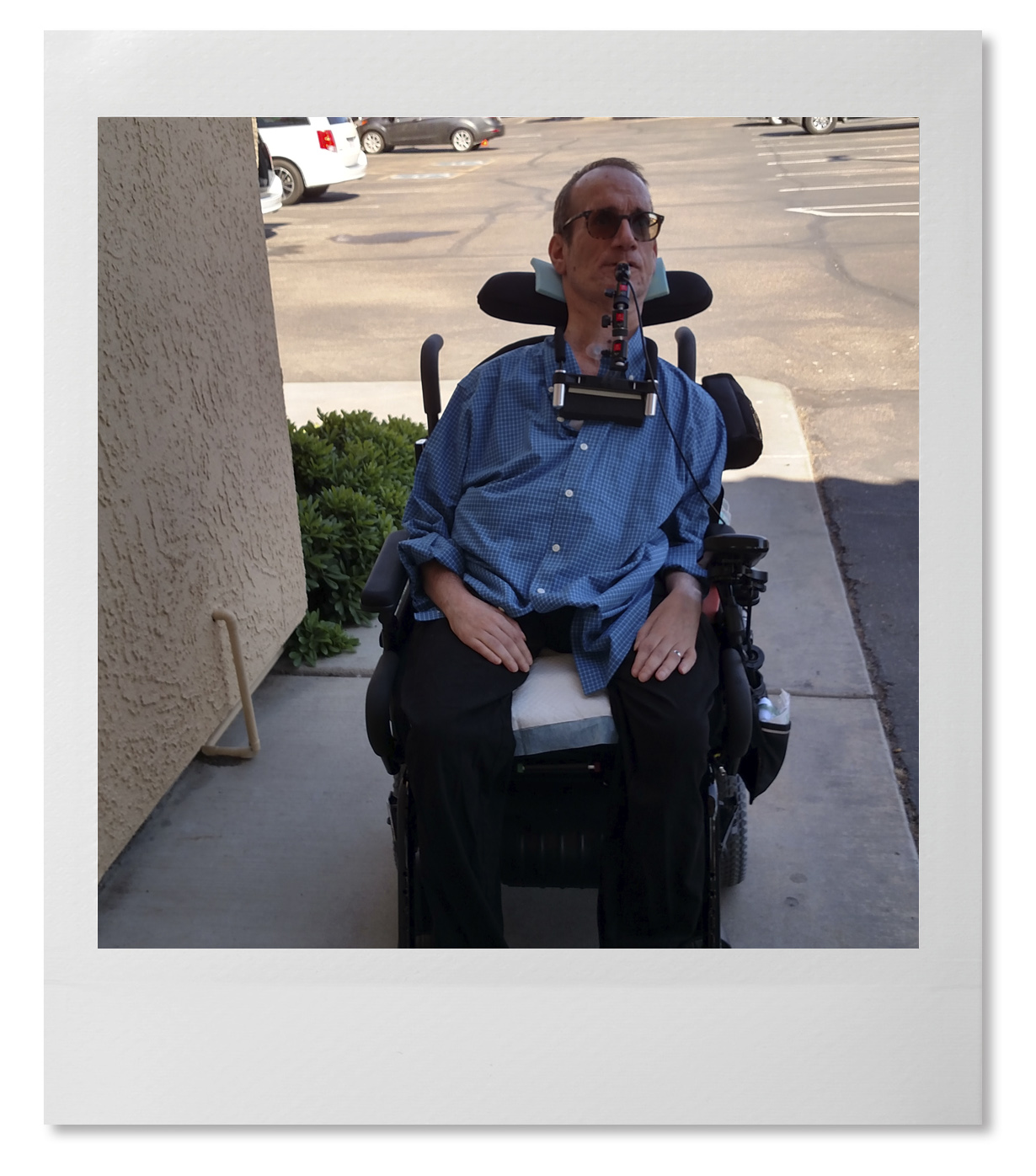

Kristen Parisi, a writer and diversity consultant from New York, was without her wheelchair for the first time in her life this summer when JetBlue lost it after a flight to a friend’s bridal shower. Kristen Parisi | Courtesy Photo

Her mind raced, trying to figure out what she would do. She’d flown to Syracuse, New York, for her best friend’s bridal shower. She remembered her parents’ dining room table included chairs with wheels. Maybe, she thought, she could use one of those at the shower.

She caught a break when it turned out her parents had one of her old, beaten-up wheelchairs at their house.

Parisi, in her 30s, resolved to not let her lost chair ruin the bridal shower. She did her friend’s makeup, drank mimosas and played Harry Potter-themed games. All the while, she was answering phone calls from the airline.

“It was the last thing I wanted to focus on that day,” she said. “My best friend is checking in on me. Yes, it’s important, but … this day should have been all about Kels finally marrying this guy.”

She later learned JetBlue found her chair sitting abandoned on a jetway. They promised to deliver it promptly as a priority item. The man who drove it to her didn’t get that message, she said, telling her he had “a bunch of other luggage to return first.” After 10 hours, Parisi got her chair back.

“Assistive devices are limbs. They’re not luggage. That’s my legs,” she said. “If I don’t have my specific chair, I can’t transfer. I can’t pick it up and fold it. I can’t go to work. My independence is taken away from me.”

Parisi used to think the Syracuse experience and others like it were bad luck, but after so many she has decided it is “systemic ableism.”

“People with assistive devices are often looked at almost as a nuisance,” she said.

Parisi said chair users experience discrimination and trauma so often it starts to feel routine rather an outrageous. That’s why she hasn’t always filed a complaint with the airlines and only recently learned that it’s a separate process to file a complaint with the U.S. Department of Transportation.

“You brush it aside, like, whatever, it’s just another ignorant person,” she said. “It’s time-consuming to file [complaints]. I’m not saying you shouldn’t. But if I filed something every time I was discriminated against, that would be a lot of times.”

Parisi sees plenty of “simple, common sense” changes that airlines could make to ensure their passengers with disabilities are as comfortable and safe as other passengers on every flight: better training for crews, improved communication between staff about passengers with accommodation requests, and transport chairs that are not broken.

“When you do a 5K, you’ve got a sensor in your bib that’s essentially a GPS unit. You can be tracked along the way,” she said. “There needs to be something where that technology is incorporated into the tags we put on our chairs. That way, you can see if your chair is at the wrong terminal in the airport. It would take two seconds to look up on your phone.”

Parisi said some of her friends who use assistive devices won’t fly at all. Those who have flown less often will call and bombard her with questions about how to minimize the risk of damage to their chairs.

“Traveling is something I get so much joy out of,” she said. “I hate the idea that someone is afraid to go simply because they’re afraid something is going to happen to their chair. That should be the last reason they don’t travel.”

Up next:

Ben Mattlin wouldn’t risk flying, so he drove 2,000 miles instead