Warnings ignored, labs slashed, expertise lost

Josh Levy struggled to breathe.

It was mid-March, just as the coronavirus was starting to claim lives in Florida. The 30-year-old Miami man called state and county health departments, trying to get tested. He warned them he had mingled with hundreds at a gala just before he got sick.

Health officials didn’t test him until his father nearly died of COVID-19. They didn’t tell him it would take eight days to get results. They never tracked the people he told them he might have infected. And they didn’t follow up to make sure he was in quarantine.

They couldn’t.

Alan Levy with son, Josh, and wife, Lynne, before the coronavirus hit, sending Alan to the hospital for weeks. Levy and his son, Josh, tried but could not get tested by the state and local health departments in early March, when they first got symptoms. Lynne Levy | Submitted

Over the past decade, politically popular budget cuts crippled the Florida Department of Health’s ability to track diseases and test for viruses, according to state budget documents, health department records and current and former health officials.

Written warnings of an inevitable viral epidemic had started piling up just before then-Gov. Rick Scott’s 2011 decision to slash millions from the only state agency capable of handling an epidemic. So did pleas for money to fix safety issues at labs and hire people who could track diseases.

Elected officials, agency heads and experts responsible for the state’s public health system knew an epidemic capable of killing thousands and decimating the state’s economy would come.

But Florida didn’t fix the problems. It contributed to them:

» Warned during the 2009 swine flu outbreak that the state’s five labs were overwhelmed and needed more trained workers, DOH instead shuttered two labs and allowed two others to repeatedly fall into dangerous disrepair.

» Despite evidence that job cuts to local health departments played a role in the spread of a 2012 tuberculosis epidemic, the state slashed 3,700 local positions. By 2016, counties had so few trained epidemiologists to track outbreaks that the overworked staff could not meet a critical threshold, the ability to effectively investigate more than one disease at a time.

» The health department in 2013 undercut its own infectious disease division, merging it with the environmental health division and cutting 300 jobs from both. The combined department oversees not only disease outbreaks, but public pool inspections and animal bites.

» After trying, and failing, to keep the scope of the 2012 tuberculosis outbreak secret amid aggressive budget cuts and department reorganization, DOH rushed to shutter and sell the state’s tuberculosis hospital. It was the only state-operated hospital that safely could have quarantined large numbers of people with COVID-19.

Officials for years warned that Florida was ill-equipped to respond to outbreaks, citing their concerns in state reports in 2010 and 2011, in a 2019 study by top health officers and in multiple budget requests over the course of a decade. But the warnings did not make it to the Legislature where they could have been openly debated.

Former state Rep. Matt Hudson, the Naples Republican who nearly a decade ago championed the sweeping overhaul of the health department, said he doesn’t recall whether they discussed the epidemic preparedness warnings.

Neither does former state Rep. Mark Pafford, a West Palm Beach Democrat who served on the House Health and Human Services Committee between 2011 and 2014, when the deepest budget cuts were being rolled out.

“Absolutely” they should have been on the table for discussions, said Pafford, who opposed the cuts. But at the time, he said, “All the work, all the effort, went into smaller government, leaner government. Planning and preparation never seemed to be a priority.”

Although the belt-tightening started before he took office, it was Scott, the former health care executive, who oversaw the most draconian cuts.

U.S. Sen. Rick Scott, right, speaks with U.S. Sen. Marco Rubio and health officials on March 6, 2020, at the Palm Beach County Health Department in West Palm Beach. As governor, Scott oversaw massive cuts in the state’s health department. Lannis Waters | palmbeachpost.com

In 2011 alone, Scott slashed $117 million from the agency’s budget, the largest such cut in a decade. He oversaw the elimination of thousands of positions at a time when Florida was adding millions of residents.

Scott, now a U.S. senator, declined to answer several specific questions about the budget cuts, including whether he was aware of repeated warnings about Florida’s need for more people and more money to counter an epidemic.

However, in a two-paragraph response, spokeswoman Sarah Schwirian wrote that, “Eliminating those positions had no impact on the Department’s ability to serve the public under Gov. Scott. Any assertion that efficiencies that were made reduced the ability to respond under Gov. Scott is false and misleading.

“We’re certainly not going to apologize for making government more efficient and effective for Florida taxpayers.”

The health department in a written statement defended its epidemic training and the expertise of its leaders. It said it contacts coronavirus patients and emphasized its emergency hiring of extra epidemiologists to handle the virus.

“The Department is constantly evaluating all processes and is open to researching new recommendations to help keep Floridians safe from any and all situations,” the agency said.

In budget documents, though, health officials worried over an economy dependent on tourism and retiree-spending coupled with the state’s subtropical petri dish of a climate. A viral epidemic, experts believed, was not a matter of if but of when.

The Department of Health and the 53 county health departments it runs have never fully recovered from the Scott administration’s cuts. The agency’s $3 billion budget has edged up under Gov. Ron DeSantis, but adjusted for inflation, it still remains at least 11% lower than it was in 2010. Among counties, it’s 25% lower.

Yet Florida’s population has grown by 3 million since the budget cuts began. The number of tourists pouring into the state has increased by more than 18 million to top the 100 million mark.

Florida Gov. Ron DeSantis speaks March 30, 2020, at a news conference with Palm Beach County Mayor Dave Kerner and County Administrator Verdenia Baker at a drive-thru COVID-19 testing facility in West Palm Beach. Greg Lovett | palmbeachpost.com

Today, among the nation’s top five tourism states, Florida is on course to be the last to recover from the coronavirus, trailing even hard-hit New York, according to University of Washington projections relied upon by the White House.

Florida won’t be able to safely open businesses and lift travel restrictions until June 14, the university projected on April 27. That’s weeks behind other heavily populated and tourist-heavy states such as Texas and California.

Florida was late to impose a stay-at-home order and close nonessential businesses, so the virus likely will spread longer in Florida than in states with a higher volume of cases, said Dr. Ali Mokdad, of the University of Washington.

And a delay in lifting restrictions in Florida will have national implications, he added. States that can safely reopen in May, for instance, will have to take tourism into consideration.

“If New York and California are ready to open up before Florida, what are the measures we’re going to have to take to test people as they’re getting off planes into and out of Florida?” Mokdad said. “These are big discussions we’re going to have if Florida can’t safely reopen.”

Gov. Ron DeSantis on Wednesday started reopening much of the state, saying he would do so carefully and methodically. He also has said he would consider adding a fourth state lab.

The governor’s office did not respond to written questions about this story. However, in an April 18 news conference, DeSantis praised the health department for contacting people exposed to the virus and isolating people who have tested positive.

That wasn’t Levy’s experience.

“I had to make the argument that the reason they should test me is because I had been in contact with hundreds of people,” he said. “It was the most chaotic and unorganized system that I could have imagined.”

Julie Grasso gets a swine flu vaccination in October 2009 at the Tabernacle Missionary Baptist Church in West Palm Beach. The swine flu killed 230 Floridians and inundated the state’s five laboratories, laying bare weaknesses and prompting warnings that Florida needed to boost epidemic preparedness. Lannis Waters | palmbeachpost.com

Ignored warning signs

The 2009 swine flu that killed 230 Floridians and inundated the state’s five laboratories laid bare weaknesses in the Department of Health’s ability to handle an epidemic.

Some state lab technicians weren’t trained to process a simple flu test, a 2010 health department report found. Others were too overwhelmed taking calls from the public to handle tests or record needed data.

Not enough hospitals had emergency plans for running out of beds.

The state’s labs processed just 15,000 tests — a fraction of what would be needed a decade later to respond to the coronavirus.

Despite those problems, Florida got lucky. The virus was not as severe as originally feared. It had not spread aggressively among older people, the 2010 report said.

“Many experts say we dodged the bullet with this pandemic and that it could have been far worse,” U.S. Rep. Gus Bilirakis, R-Gainesville, said at a January 2010 congressional hearing on the swine flu.

Vials of swine flu vaccine offered to residents for free in October 2009 at a West Palm Beach church. State health officials were relieved the virus did not spread as aggressively as initially feared. Lannis Waters | palmbeachpost.com

The state needed to hire more scientists and epidemiologists, train its workforce and beef up its labs, the 2010 health department report urged.

But in 2011, as Scott’s administration honed its budget-cutting axe, the Department of Health started doing the opposite.

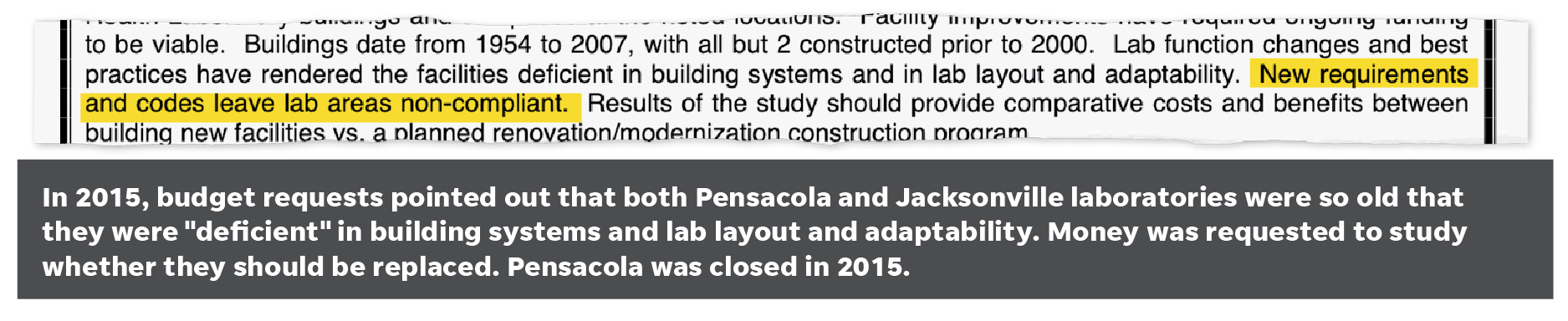

In 2012, DOH shuttered its Lantana lab in the middle of an historic TB outbreak. In 2015, it closed a second lab in Pensacola.

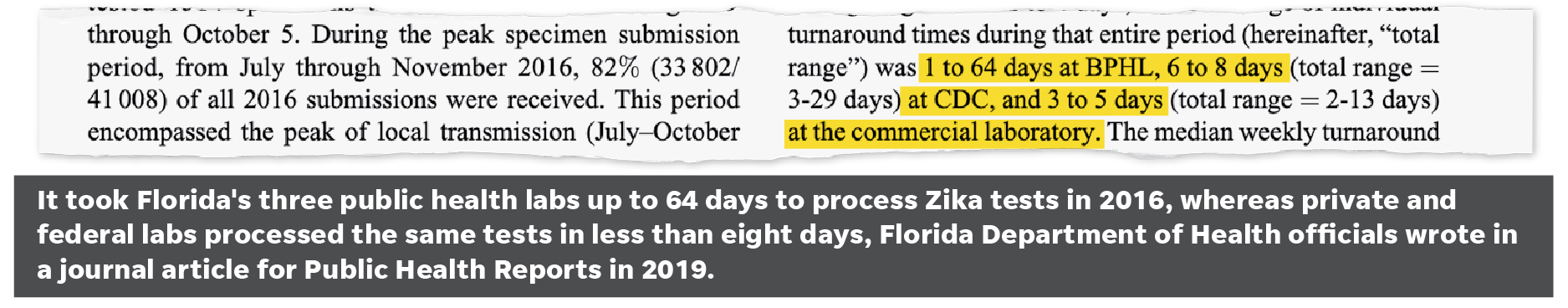

The next year, when Florida recorded its first case of the mosquito-borne Zika virus, the three remaining labs were overloaded.

Laboratory staff in Tampa worked 18 to 20 hours a day, the head of the lab later told the Association of Public Health Laboratories. But even running full throttle, it took up to 64 days to process Zika tests, a 2019 analysis by state health officials found. It’s one reason why federal and commercial laboratories were handling 80% of Florida tests.

Quick testing is crucial to containing an epidemic. Doctors need to be tested to make sure they are not spreading the disease they are treating. It identifies “hot spots” in the outbreak. People can get help faster.

The acceptable turnaround time for a Zika test result, according to the report: No more than four days.

In late February, Florida Deputy Secretary of Health Shamarial Roberson told reporters that the same three state labs that could not quickly handle Zika in 2016 would produce coronavirus tests results in 48 hours.

Instead, waits stretched to 13 days in some cases, delaying treatment and risking further contagion as people with mild cases continued to work, shop and socialize.

Within two weeks, Florida inked $1 million in emergency contracts with private labs to pick up the testing slack.

Inundated state labs are now processing only one in every 10 tests, according to health department figures.

Demolition began in November 2014 on the A.G. Holley State Hospital in Lantana. It is now the site of high-end homes. Damon Higgins | palmbeachpost.com

Infectious disease hospital closed

If the swine flu exposed shortfalls, cost cuts also did away with the only state-operated hospital capable of quarantining large numbers of patients with an airborne disease.

The 100-bed A.G. Holley State Hospital in Palm Beach County, designed for tuberculosis patients, was renowned for curing hard-to-treat cases.

Dr. Claude Dharamraj, former director of the Pinellas County Health Department. University of South Florida | Submitted

Florida was three years into the worst tuberculosis outbreak in a generation when Scott signed sweeping legislation closing the 100-bed facility.

The outbreak was largely secret, though. As the Centers for Disease Control told Florida officials about both its scope and what would be needed to contain it, officials simply sped up plans to sell the TB hospital. A proposal to build a new hospital with money from the sale was dropped. It’s now the site of high-end apartments.

Almost everything Holley offered would have been useful in battling the coronavirus. It had controlled air circulation. It had isolation rooms. Staffers were experienced at dealing with airborne disease and patients with more than one medical issue, such as nursing home residents.

But especially in the early days of the coronavirus crisis, stricken nursing home patients were left in those facilities, infecting others. A cruise vessel remained moored and effectively quarantined off the coast, allowing infection to spread among crew and passengers.

“You may not have TB as a problem in that moment, but you keep those epidemiologists, you keep that isolation hospital,” said Dr. Claude Dharamraj, former director of the Pinellas County Health Department.

“You keep them for the next disease that comes, because it will come.”

In 2012, Florida shut down A.G. Holley State Hospital in Lantana near West Palm Beach, one of the nation’s last dedicated tuberculosis hospitals, even as one of the worst TB outbreaks in 20 years raged uncontained in Jacksonville. Lannis Waters | palmbeachpost.com

Inside the A.G. Holley State Hospital in Lantana as officials shut it down in October 2012. Despite a tuberculosis outbreak, state health officials pushed up the hospital’s sale date as part of cost cutting efforts. Lannis Waters | palmbeachpost.com

Labs in disrepair

Florida’s three state laboratory campuses in Jacksonville, Tampa and Miami track and test some of the most dangerous pathogens in the world, including those causing swine flu, Zika and MERS, a virus that kills three of every 10 people it infects.

But just months before COVID-19 slammed into the state, aging equipment crucial to safety or operations were failing. But thousands of coronavirus specimens were sent to the same labs anyway, despite their ongoing, years-long list of needed work.

There is no evidence that incomplete or delayed lab repairs harmed workers or the public. But budget requests show that state health officials knew they were repeatedly risking safety by not promptly paying for repairs and renovations.

For instance, DOH requested money to complete a fire sprinkler system in a Jacksonville laboratory building in 2013. In 2016, DOH was still requesting money to finish installing sprinklers in the building. In another building on the campus, the state initially paid for fire sprinklers for only one of three floors.

“If you have a fire in the lab, it doesn’t mean that all the pathogens burn up,” said Beth Willis. Willis chaired a Maryland advisory committee of scientists and community members focused on ensuring safety at nearby high-level Army laboratories. “It means you have broken containment.”

Walk-in coolers are needed to store specimens and vaccines. Incubators are needed to grow cells for research and testing. Statewide in 2019, certain Florida lab coolers and incubators were so old — 18 to 28 years — that they were no longer being manufactured.

Chemical ventilation hoods, which limit exposure to hazardous materials, had not been replaced since some labs were first built, a “critical” issue at all three of the state’s lab sites.

Specialized ventilation and air handling are required to keep lab staff safe, research intact and viruses from escaping into the community. Throughout the Miami laboratory complex, “significant” parts of the air-conditioning system were 40 years old in 2019, providing “erratic” climate control, officials wrote in budget requests.

Critically, a high-level lab at the complex specifically handling the lethal swine flu virus needed unspecified “immediate” repairs: Both its safety and its continued operations depended on it.

Kevin Graham lived at Golden Retreat Shelter Care Center in Jacksonville in July 2012 when the assisted living facility housed a person with tuberculosis. Few knew the scope of the outbreak when lawmakers voted to shut down the state’s lone TB hospital in Palm Beach County. Palm Beach Post | File Photo

An experience exodus

More than jobs disappeared with budget cuts.

Employees who had dealt with past epidemics left as money dried up for training that could have offset new hires’ inexperience.

By 2018, four in 10 state lab scientists — most of them paid a wage roughly equal to a McDonald’s store manager — were quitting after just two years on the job.

Roughly one-third of county health department heads did not hold their current jobs during the 2009 swine flu pandemic and the 2012 tuberculosis outbreak, both spread by airborne viruses.

Medical backgrounds might help in meeting the current pandemic, but fewer than half hold a medical, nursing or osteopathic degree, according to their DOH-published biographies.

Several come from backgrounds in business, not health: One county department executive is a former manager of a small city and a self-help author. One is a former school district administrator. Four have accounting backgrounds.

Even with experienced employees, training is key. But the last statewide pandemic drill in coordination with the Centers for Disease Control took place in 2011.

“We set the course of public health actions during disasters and we were the ones forced to tighten the belt year after year,” said Mike McHargue, who headed training and preparedness at the health department until 2015.

Before the sweeping budget cuts, the Centers for Disease Control lauded Florida for the “impressive caliber” of its epidemiologists and their ability to track disease.

Epidemiologists are the foot soldiers deployed when there is even a hint of an emerging disease, “the tip of the spear for attacking this kind of outbreak,” said McHargue of the coronavirus. They spot and analyze patterns. They guide decisions on where to focus resources.

With each wave of budget cuts, though, the department slowly lost that ability, said McHargue. “It was quite devastating.”

Florida had to use emergency cash from the federal government in 2015 to hire 21 epidemiologists during the Zika outbreak. In 2016, budget documents show that there weren’t enough trained staff at the county level to quickly and effectively track more than one potential outbreak at a time.

The state has hired 223 epidemiologists to respond to the coronavirus, bringing the number of epidemiologists now working on the epidemic to more than 500, DOH stated.

However, epidemiologists are needed in the very first days of a disease outbreak, before it has time to spiral out of control, several experts told Gannett USA TODAY NETWORK.

Cynthia Harris, director of the Institute for Public Health at Florida A&M University. (Florida A&M University)

During the 2012 tuberculosis outbreak, for instance, the Duval County Health Department was responsible for tracking people who had come into contact with the schizophrenic man believed to be the original case. They needed to find 440 people.

Over the next three years, the department lost 246 employees and 25% of its budget.

Without enough staff to find people who had been exposed, the number of those who needed to be located and tested swelled to 2,488 in those three years, The Palm Beach Post first reported.

Before the outbreak was stopped, it spread to 18 counties. A barber appeared to have given it to a 14-year-old. A teenager was exposed in a juvenile justice center. Thirteen people died. Another 99 were sickened.

“It’s just mind-boggling to me — given the size of our state, the rates of HIV/AIDs and other diseases and a large elderly population — the willingness to cut the positions that stop the spread of disease,” said Cynthia Harris, the director of the Institute for Public Health at Florida A&M University.

Alan Levy and his wife, Lynne, wave to a parade of friends and neighbors passing their Boca Raton home April 21, 2020, welcoming Alan home after his hospitalization with COVID-19. Levy and his son, Josh, had unsuccessfully tried to get tested by their local health departments when they felt they had coronavirus in early March. Allen Eyestone | palmbeachpost.com

‘Almost killed my dad’

Josh Levy waited more than a week to get his coronavirus test results.

But he didn’t wait to start calling people he’d rubbed elbows with at a March 5 gala at his Miami-Dade County synagogue. That was just days before his headaches and dry cough started. At that point, Florida had reported only five coronavirus cases in the entire state.

The government didn’t take this seriously. Now is not the time for me to do the same.

With the pandemic in its early stages, some accused him of fear-mongering. Others shrugged it off. Many compared it to the common flu.

“It almost killed my dad,” he would tell them. “This is nothing like the flu.”

Levy tested positive. The day he got his test results back, the rabbi of his synagogue, who had attended the gala, tested positive for the coronavirus. So did one of Levy’s close friends.

Levy said health officials never called him or his father to ask whether they potentially had exposed others — though Levy said he offered the information in at least one phone call with the state.

It’s been three weeks since his symptoms stopped, longer than the CDC’s recommended 14-day quarantine after a positive test.

Levy plans on staying home.

“I’m playing it safe,” he said. “The government didn’t take this seriously. Now is not the time for me to do the same.”

“Mr. Levy you did it,” says the sign outside the Boca Raton home of Alan Levy, who survived a hospital stay with COVID-19. Allen Eyestone | palmbeachpost.com

Andrea Wildman, left, Josh Levy and Carol Kaplan wave April 21, 2020, to neighbors and friends in Boca Raton welcoming home Josh’s father, Alan. Allen Eyestone | palmbeachpost.com

Support local in-depth journalism like this.

Subscribe to The Palm Beach Post or subscribe to USA TODAY.

Palm Beach Post investigative reporter Lulu Ramadan worked with Gannett USA TODAY Network on this story and can be reached at lramadan@pbpost.com.

Gannett USA TODAY NETWORK senior investigative reporter Pat Beall can be reached at pbeall@gatehousemedia.com.

U.S. Sen. (and former Florida Gov.) Rick Scott’s statement

We’re certainly not going to apologize for making government more efficient and effective for Florida taxpayers. The majority of the positions you mentioned were vacancies that were dormant. Eliminating those positions had no impact on the Department’s ability to serve the public under Governor Scott. Any assertion that efficiencies that were made reduced the ability to respond under Governor Scott is false and misleading.

Under Governor Scott, Florida’s public health network was nationally recognized for its quality and efficiency. Florida is the first, and only, state in the nation to have its statewide health department and every county health department pass the rigorous, peer-reviewed accreditation process. Governor Scott guided Florida through numerous crises, including the Zika outbreak, and deftly managed state resources to serve the needs of Florida families. He left the Department of Health and county health departments in a great position to continue to do so.

Sarah Schwirian, press secretary, Sen. Rick Scott

Tuesday April 21, 2020

Florida Department of Health statement and response to questions

The Department of Health continues to follow CDC guidance. As the COVID-19 outbreak has evolved, CDC guidance has changed to recommend self-monitoring for symptoms. Florida Department of Health has produced educational materials to help with this effort.

Wednesday, Governor Ron DeSantis held a press conference at the Florida Capitol and announced that two more private labs have been contracted to complete COVID-19 testing. These two new labs will be able to process 18,000 samples per day with results being processed within 24-48 hours.

The DOH-Alachua County Administrator does not hold dual roles. Additionally, there is a dedicated Director for Florida’s Office of Medical Marijuana Use.

The Department contacts persons who test positive for COVID-19 and asks them to identify their close contacts. The Florida Department of Health has more than 500 epidemiologists dedicated to responding to COVID-19, this includes 223 epidemiologists hired during the response and approximately 300 DOH epidemiologists not including the HIV, STD, Tuberculosis programs. Epidemiologists verify whether close contacts work or reside in health care settings, or are linked to outbreaks. Department staff also provide education to the case about how they need to care for themselves and their family while ill to avoid further disease transmission.

The Department is constantly evaluating all processes and is open to researching new recommendations to help keep Floridians safe from any and all situations. Efforts have been made to assure that all divisions within the Department are staffed with quality employees who are able to provide expertise toward assisting during health emergencies affecting the state.

The Training and Exercise staff are a team of professionals with a wide range of knowledge and expertise, dedicated to providing a streamlined process to accomplish your educational, training and exercise goals. We test exercise capabilities which are independent of the hazard.

Our staff strives to support Florida’s public health and health care partners to ensure each are properly trained, provided opportunities to practice their emergency response roles, and are well prepared to perform those response duties for any and all hazards.

Our Emergency Preparedness Team consists of seasoned DOH staff and Master Exercise Professionals that are well versed in the Homeland Security Exercise and Evaluation Program process. We have access to many subject matter experts in public health and medical and are ready to provide support in design, development and execution.

Leveraging resources through proactive planning and strategic collaboration with a variety of local, state and federal partners allows the Department to evaluate and prevent potential health risks from chemical, biological, radiological and physical agents in the environment.

Statewide exercises and After Action Reports can be found here

Additional information can be found on the Department’s Emergency Preparedness and Response website.

Thank you,

Alberto Moscoso, communications director, Florida Department of Health

April 24, 2020