How the rise of

out-of-hospital

births puts mothers

and babies at risk.

Presentation includes sound A

Begin911 what’s the nature

of your emergency?

I’m a midwife attending a birth.

Hi, I’m a midwife.

She’s doing a home birth.

We have a failure to progress.

She’s gonna need a transport

over to the hospital.

How old is she? Is she breathing?

Is this her first delivery?

Can you see any part of the baby now?

Help is on the way.

I can’t get her to answer. Ma’am.

Please come, please come right now.

Oh my gosh. The baby’s

not breathing.

Click anywhere to skip K

Nov. 25, 2018

By Emily Le Coz, Josh Salman and Lucille Sherman

Baby Aquila never took a breath.

Her limp body slipped from between her mother’s legs in a river of blood during a Texas home birth in December 2009. The certified professional midwife, who missed a cascade of earlier indications of the baby’s distress, tried to save the girl. But she had locked her medical kit in the car and had to improvise.

So she sucked blood from the baby’s airway and spit it on the floor. Sucked more and spit. Sucked again and spit. Over and over until the room looked like a crime scene. Paramedics arrived minutes later.

But it was too late. The baby died from an infection with symptoms that should have prompted the midwife to call 911 sooner, according to a state investigation D.

Liz Paparella buried her daughter two days before Christmas.

“I had always heard home births were safer,” Paparella said, “but it’s not true.”

Planned births outside the hospital nearly doubled nationally in the past decade, riding a wave of disdain for the medicalization of pregnancies. Rather than endure the epidurals and C-sections, women sought a more natural experience.

Enter the midwife; an anachronistic figure boomeranged into the mainstream and rendered reassuring by popular TV shows and documentaries — the BBC hit “Call the Midwife” among them.

Midwives offer unmedicated, vaginal childbirth at the mother’s own pace and in the comfort of her own home or at one of the hundreds of freestanding birth centers opening across the country.

Nearly 60,000 women had an out-of-hospital birth last year alone, most without incident.

But it’s a deadlier practice than hospital deliveries, and it leaves families little recourse when something goes wrong.

Most out-of-hospital midwives lack nursing degrees. Some can’t administer drugs. Few carry adequate lifesaving equipment. Many are afraid to call 911 when emergencies arise. Almost none are required to have liability insurance. More than a dozen states don’t even regulate them.

GateHouse Media and the Sarasota Herald-Tribune spent nine months investigating the out-of-hospital birth industry. Reporters interviewed more than 100 mothers, midwives, physicians, attorneys, lawmakers and researchers. They read thousands of pages of disciplinary records, regulations, lawsuits and studies. They analyzed state and national birth and infant death data. They crisscrossed the country, visiting birth centers and hospitals, and even followed a mother through her home birth.

Among the findings:

- Midwives woo pregnant women by promising safe, out-of-hospital births. They routinely downplay the risks, overstate their capabilities and vilify the medical establishment. Babies born at home or in a freestanding birth center are twice as likely to die and suffer lifelong injuries as those delivered at a hospital. That data doesn’t count most hospital transfers, meaning the true risk is likely higher.

- Midwives and physicians don’t trust each other, and it exacerbates the danger. Midwives sometimes won’t refer high-risk mothers to physicians or call 911 when births go wrong. Midwives blame doctors for unnecessary interventions; doctors blame midwives for unnecessary gambles. The cross-camp collaboration safeguarding the practice in other nations doesn’t exist in the United States.

- Midwives should oversee only uncomplicated pregnancies. But they routinely flaunt risky procedures like vaginal births after previous C-sections. Some midwives break laws to give women the birth experience they seek.

- Midwives go by an array of confusing titles that obscure the chasm of educational differences and competencies that separate them. Some have graduate degrees; others high school educations. Some can prescribe medicine; others cannot. Expectant mothers often don’t know the difference — and it can be deadly.

- Families who complain about adverse out-of-hospital deliveries risk backlash from the natural birth community. Many are blamed for their own babies’ deaths. And they have little assurance their midwives will be held accountable. The feeling of helplessness drove one New York woman to suicide this year.

“You might lose it all just to have a baby at home,” said Charlie Romanelli, a New York father whose wife and infant son died in an attempted home birth in 2011. “You hear the nice stories. You hear the Ricki Lake stories, the empowerment stories. But you don’t hear about the people who are dead. The mothers who are dead and the babies who are dead or brain damaged.”

To be sure, no childbirth is without risk. The best doctors in the best hospitals can have adverse outcomes, as evidenced by America’s high maternal and fetal mortality rates compared with other industrialized nations.

Midwifery has been shown to reduce those death rates in other countries, especially those lacking access to doctors and hospitals. And their care lowers unnecessary medical interventions in the United States and abroad. Midwives offer women a more personalized choice in prenatal, perinatal and postnatal care.

“In the hospital, she’s treated like she’s sick, and she’s treated like everybody else,” said Oklahoma-based certified professional midwife Venessa Giron. “Whereas with midwives they know that the care that they’re getting is very individualized.”

It also should be noted that most out-of-hospital deliveries end well in America. Infant death remains rare regardless of birth setting, and occurs at a rate of roughly 1.3 per 1,000 full-term babies born at home or in a freestanding birth center, based on a GateHouse analysis of data from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

But that’s still double the death rate of hospital-born babies.

“The occasional bad outcomes that occur in hospitals are widely known,” said Steven Clark, a leading childbirth safety expert at Baylor College of Medicine. “On the other hand, home birth has some of the most incredible attempted cover-ups, like burying babies in the backyard, which is something I’ve experienced in my career. So, for a mother who’s vulnerable, you’ll never hear the bad stories from home.”

Actress Ricki Lake reclines in the tub of a dimly lit bathroom. She breathes heavily as a newborn slides out from between her legs.

His arrival appears effortless. With the help of a certified nurse midwife, Lake reaches for her son and pulls him onto her chest, cradling him in the warm water.

“Oh my gosh, you’re gorgeous,” she coos, as the midwife adjusts the umbilical cord and strokes the baby’s skin with a cloth. Mother and baby bond as the child first opens his eyes and eventually cries. Lake covers his head with kisses.

It’s a quiet, cozy and familial scene in the 2007 documentary “The Business of Being Born.” The feature-length film, co-produced by Lake, contrasts tender moments of home births with black-and-white footage of hospitals blindfolding pregnant women, strapping them to beds and forcing upon them unnecessary interventions.

Its message: Home births empower women; hospital births subjugate them.

Midwifery and home births were the norm for generations, until medically managed hospital births all but drove the practice underground by the late 1960s. Rural, religious or counterculture families largely accounted for the less than 1 percent of home birthers who bucked the trend.

The low rate remained unchanged for decades.

But growing concerns about hospitals’ skyrocketing C-section rates W, which surpassed 30 percent by 2005, rekindled an interest in home births. This coincided with the release of “The Business of Being Born,” which many midwives recommend to their clients and many women say informed their decisions.

“I watched the ‘Business of Being Born,’ and it really made sense to me at the time,” said Florida mother Chelsie Shock, whose 2014 out-of-hospital delivery resulted in severe blood loss that could have cost her her uterus. “I was very naïve.”

From 2005 to 2017, U.S. out-of-hospital birth rates nearly doubled from 0.8 percent to 1.5 percent. It’s even higher in western states like Montana, Washington and Oregon, where nearly four in 100 babies are born outside a hospital, CDC data show.

One-third of these deliveries happened in homes. The rest occurred in freestanding birth centers, most of which are unaffiliated with hospitals, operated by midwives, and resemble bed-and-breakfasts with plush furniture, tasteful artwork, and deep bathtubs. Not all are regulated or accredited.

Women who never would have considered the practice a decade ago now see it as a reasonable option.

They’re often told it’s just as safe: “There is no difference in infant mortality between midwife-attended and physician-attended births for low-risk women,” according to the Midwives Alliance of North America.

For in-hospital births, that is true. It’s also true in countries like the Netherlands D and Canada D — both of which require D midwives to have bachelor’s degrees, offer both in-hospital and out-of-hospital births, and be fully integrated into the health care system.

But it’s not the case in America, where some midwives have no more than a high school education and where more than a dozen states let anyone practice without rules or oversight.

“It’s not really apples to apples,” said Louise Aerts, registrar and executive director of the Canadian Midwifery Regulators Council.

U.S. babies are twice as likely to die during — or within a month of — delivery when born at home or in a freestanding birth center as babies born at a hospital, according to a GateHouse Media analysis of CDC data on more than 35 million live births from 2006 to 2015.

That risk climbs when comparing only babies delivered by midwives.

Infants are three times as likely to die with midwife-assisted home births as midwife-assisted hospital births. In hospitals, midwives are advanced registered nurses who perform the kind of low-risk, uncomplicated deliveries that out-of-hospital midwives are supposed to handle at home.

Physician-assisted deliveries have higher fatality rates because they must accept all risks.

The mortality rate climbs again for babies of first-time mothers, who are four times more likely to die.

When restricting the same analysis to deaths within one week of delivery, babies delivered by a home midwife are five times more likely to die.

For babies of first-time moms, the rate climbs eightfold.

“There’s no question that many more babies die. The only conflict is that midwives are not honest about it,” said Amy Tuteur, an obstetrician-gynecologist and former clinical instructor at Harvard Medical School. Tuteur is an outspoken and sometimes controversial critic of home births whose opinions have been published in The New York Times.

“Certified professional midwives have terrible outcomes compared to everyone else,” Tuteur said. “They’ll point to statistics in the Netherlands, and say, ‘Look. Midwives are so great.’ But that’s not them. It’s a bait and switch.”

The GateHouse analyses track with previous, peer-reviewed, CDC-based research D conducted by Amos Grunebaum, an obstetrician-gynecologist affiliated with New York-Presbyterian Hospital.

“It’s pretty clear it’s a dangerous undertaking,” said Grunebaum. “Mothers are being cheated. They are being given a false bill of goods from snake oil salesmen.”

The North American Registry of Midwives disputes out-of-hospital births are riskier.

“In a perfect world, mothers would know there are no extra risks to home birth versus hospital births,” said Debbie Pulley, who oversees public education and outreach for NARM. “But they’re different risks.”

Researchers say the risks are even greater, because the data doesn’t capture hospital transfers. Babies compromised during an attempted home birth but who are delivered or pronounced dead in the hospital count against the hospital.

Such was the case of Franklin Riley. His mother delivered him by emergency C-section after he went into distress during an attempted out-of-hospital birth in December.

“My husband and I had been trying for four years to get pregnant — and at that point, we didn't think we could anymore,” said Athena Riley. “It was just such an exciting time for us to know we could bring a child into this world.”

The laboring mom didn’t know her son was breech W when she checked into Gentle Birth Options, a freestanding birth center in the Florida Panhandle community of Niceville. Riley trusted the midwife to guide her through the process.

But Cynthia Denbow, a certified nurse midwife and birth center owner, didn’t check the baby for more than an hour. By the time she discovered its bottom-first position, Riley was fully dilated and ready to push, according to Florida Department of Health records D.

Florida restricted Denbow’s nursing license in February, claiming she failed to seek physician involvement and then attempted to cover it up. Denbow is challenging the sanction.

Most regulated states require hospital transfer or physician consultation because breech babies can get stuck in the birth canal. The majority are delivered by C-section.

Denbow called no physician. She encouraged Riley to stay at the birth center and push.

Riley did so for 22 minutes, as her unborn son went into distress and Denbow finally called 911. Doctors at Fort Walton Beach Medical Center delivered Baby Franklin by emergency C-section and rushed him to the neonatal intensive care unit for resuscitation. They couldn’t save him.

His death counts, statistically, as a hospital loss.

Denbow declined to comment, instead referring questions to her attorney, Suzanne Hurley, who said the baby had existing heart problems and would have died anyway. Riley’s attorney, Virginia Buchanan, disputed this, citing the autopsy, which shows the baby’s heart failed due to stress caused by birth trauma and asphyxiation.

“There is no question — zero question — that this baby would have survived had a timely C-section been done,” Buchanan said. “There was nothing wrong with their baby — he was healthy and full term. Any problems with the baby were caused by problems in the delay of the delivery.”

The family sued Denbow and her now-defunct birth center in May. Denbow denied responsibility for the death in a court document. The case is ongoing.

“We trusted her,” Riley said. “I wish we would have known. I really wish we would have known."

In Oregon, birth certificates indicate both the actual and intended place of delivery to better track the outcomes. In 2015, researchers used state data to conclude out-of-hospital births are more than twice as likely to result in death. The study was published in the New England Journal of Medicine.

A brochure from Central Florida’s Heart 2 Heart Birth Center compares the midwifery way of birth to that of hospital obstetrics in a chart with multiple points.

For example D: The midwifery birth setting is homelike and familiar while the hospital scene is bureaucratic and alien to women. Midwives are empathetic while obstetricians are threatening and punitive. Midwives are often mothers themselves; obstetricians are usually men and have never had babies.

The out-of-hospital birth community disavows the notion of pregnancy as a disease and blames doctors for stripping the experience of its power and dignity. Women for years have complained about the cold, clinical feel of hospital delivery.

Even doctors concede the bad reputation is well-earned. They’re trying to change by offering cozier birthing rooms, performing fewer C-sections and embracing natural labor and delivery. Most obstetricians today are women.

But midwives already have capitalized on the negative stereotypes. Many are reluctant to involve physicians unless something goes horribly wrong, which, by then, could be too late.

Even a five-minute delay in childbirth can be catastrophic.

Hospital obstetricians across the country told GateHouse Media about the last-minute transfers that haunt them to this day.

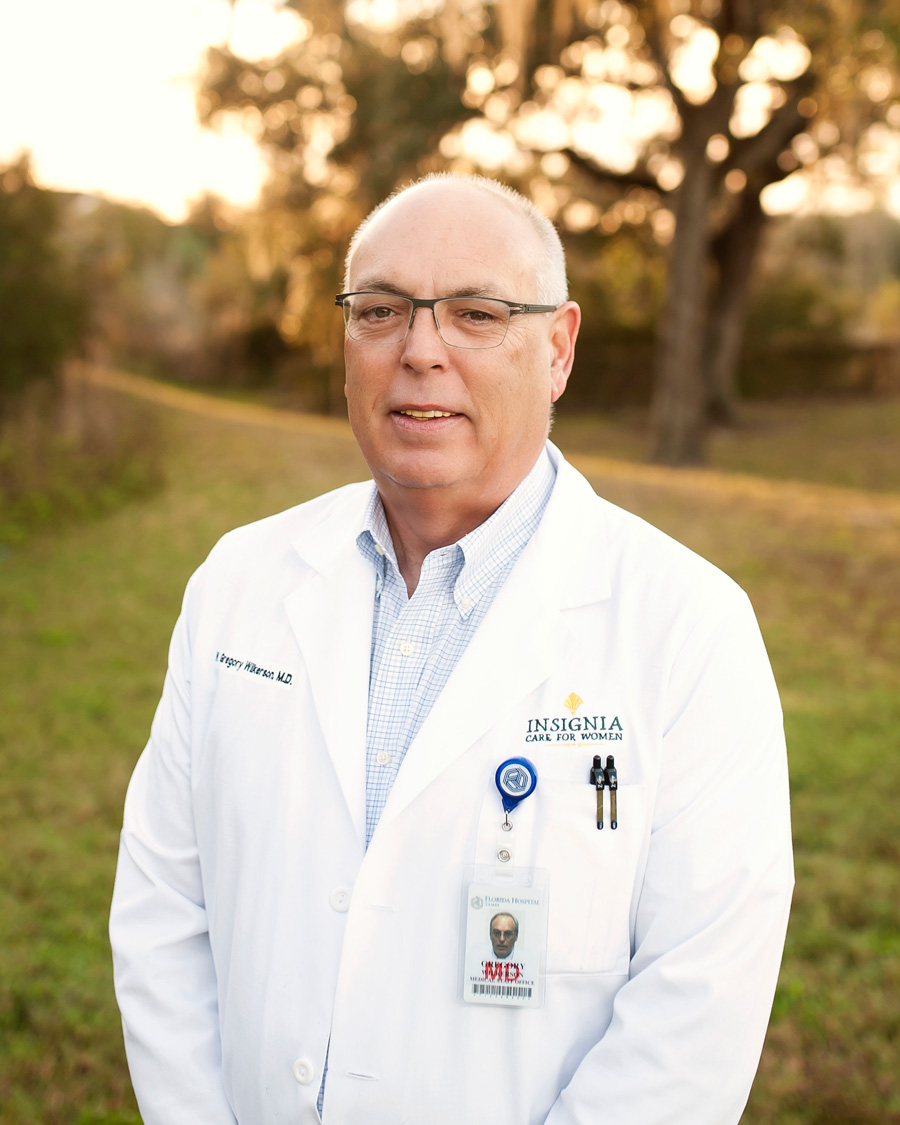

“I have seen a midwife miss a breech delivery, and the baby’s head got stuck, and that baby will be damaged for life — life support and feeding tubes — and I have seen a patient whose baby had shoulder dystocia for 12 minutes, and the baby died,” said W. Gregory Wilkerson, chief of obstetrics and gynecology at University Community Hospital in Tampa.

The worst fear among on-call obstetricians isn’t what comes through the emergency room, Wilkerson said. It’s what comes in from the community birthing center.

“Shame on our health system,” Wilkerson said, “for not monitoring this and allowing it to happen.”

Melinda Pino and Shawn McKee knew none of that when they hired licensed midwife Deborah Jacobs Marin to deliver their first child, Maddie, in a South Florida birth center. They wanted an out-of-hospital experience after watching “The Business of Being Born,” they said.

Marin told them about the dangers of hospitals, forced epidurals and C-sections, the couple said. The midwife made similar statements to the South Florida Sun Sentinel D newspaper in 2012.

But Marin promised she would transfer Pino in case of emergency, as state regulations require.

Instead, the midwife let Pino actively labor for hours while her baby was stuck inside the birth canal, her head turtling in and out. The little girl suffered irreversible brain damage from a lack of blood and oxygen, court records D show.

When Maddie finally emerged, she was covered in thick, pea soup meconium — the baby’s first stool — which stained her fingernails yellow, Pino recalled. She didn’t cry. She was purple and not breathing. Only then did Marin yell for someone to call 911.

The little girl lived in a semi-vegetative state until she died in February 2013, three days before her third birthday.

Had they gotten to the hospital sooner, doctors told the couple, Maddie likely would have been OK.

The family sued Marin, who denied the allegations in a court document but agreed to a settlement. Marin did not return calls for comment.

“You hire these people to guide you,” Pino said. “I’ve never done this before. I don’t know what point the situation becomes an emergency. That’s not the job of the mother.”

But midwives who do transfer clients to the hospital risk harassment. Doctors and nurses have banished them from the labor and delivery ward, filed complaints against them with regulatory boards, and mistreated their clients.

“Hospitals are openly hostile to home-birth midwives,” said Karen Baker, a longtime certified professional midwife licensed in California. “If they’re not hostile, they’re at least apathetic. It is a serious problem.”

Some midwives told GateHouse Media the enmity factors into their decision about whether to transfer — even in dire situations. They blame doctors for creating the rancor. Doctors blame the midwives.

The mutual distrust exacerbates the danger of an already risky practice, experts said.

“That toxic relationship leads to further delays in the quality of care,” said Aaron Caughey, chair of the Oregon Health & Science University’s Obstetrics and Gynecology Department and co-author of the 2015 Oregon infant death rate study. “Improving that relationship is going to be very important.”

Both sides acknowledge increased collaboration would improve the situation, but physicians in particular cite a reluctance to bridge the gap for a variety of reasons, including a lack of educational and regulatory standards.

“I guess the real question is, why do we allow a less-trained, less-educated group of professionals to provide care without oversight?” said Hal Lawrence, who was executive vice president and CEO of the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists when GateHouse Media interviewed him in August. He retired in October.

When physicians do work with non-nurse midwives, the relationship can cost them.

As an on-call obstetrician at Centennial Hills Hospital in Las Vegas, Steven Harter developed a reputation as a sympathetic provider. He sometimes allowed midwives to continue caring for clients transferred into his care, whereas other physicians relegated them to the waiting room. He also dispensed advice to midwives who sought it.

As a result, midwives considered him their “backup physician,” though he said no formal relationship existed.

Then one such midwife transferred a client to Harter after an attempted home birth during which the baby’s heart rate accelerated and the mother, who had an untreated group B strep W infection, ran a fever. Harter delivered the boy by C-section, by which time he had suffered a catastrophic brain injury.

The family sued D Harter, citing him as the midwife’s backup. Harter denied liability. The case settled in 2015.

“After the case, not only did my rates go up,” Harter said, “I was forbidden by my insurance company, upon threat of losing coverage, never to accept another home birth transfer.”

Midwives are supposed to handle only normal pregnancies and uncomplicated deliveries, according to best practices and most state regulations. All other cases should be referred to physicians.

But out-of-hospital midwives routinely accept high-risk patients. Among them: mothers with a history of previous pregnancy-related complications, those carrying babies beyond their due dates, and mothers who are older, overweight or managing medical conditions, all of which raise the odds of potential problems.

The North American Registry of Midwives itself condones high-risk pregnancies.

“We don’t tell midwives what they can do and what they can’t do,” said Debbie Pulley of NARM. “The mother has to know what the risks are. It’s the state’s responsibility to protect mom and baby.”

But hundreds of NARM midwives, including Pulley, practice where it’s unregulated or unlawful. They make their own rules.

Even in regulated states, some midwives skirt the rules. For example, they can alter due dates or induce women to avoid common restrictions on delivering post-term babies, said Leigh Fransen, a former certified professional midwife licensed in South Carolina.

“We will just use any clinical information we can find to move the due date,” she said, “whether that’s something on the ultrasound that maybe could date the baby as being a little younger, or maybe asking the mother, ‘Are you sure your last menstrual cycle date was such-and-such a date,’ because if it wasn’t, that could buy us a little extra time.”

Fransen attended the International School of Midwifery in Miami before moving to South Carolina and opening a freestanding birth center in 2009. She stopped practicing in 2013 and now whistleblows on the industry through her blog, the Honest Midwife.

As a student, Fransen said, she learned how to slip the labor-inducing drug Cytotec into women’s vaginas when they exceeded their due dates. She said the pill was crushed into a powder and inserted along with a capsule of evening primrose oil — an herb that helps soften the cervix.

Although non-nurse midwives can use herbs, Florida prohibits them from inducing labor with medicinal drugs.

Clients at the school’s freestanding birth center, Miami Maternity Center, never knew they were being medically induced, Fransen said.

“That’s why we had almost no referrals for people going to 42 weeks,” she said. “Because at 41 and a half weeks, everyone was getting their membranes stripped by Shari, and everyone was getting Cytotec by Shari.”

Shari Daniels was the founder of the school and the maternity center. The certified professional midwife voluntarily surrendered her state midwifery license in 2014 after facing sanctions for infractions involving at least seven patients — two of whom lost their babies, state records D show.

Among her violations: administering drugs without a prescription, using vacuums to deliver babies, and failing to transfer women past their due dates. Daniels admitted neither guilt nor innocence in the relinquishment. She is no longer affiliated with the birth center. The school closed in 2015.

Birth center office manager Dahlia Porter, who also took over the school after Daniels’ departure, said none of the midwives there practice unlawfully. Daniels could not be reached for comment.

The situation doesn’t necessarily represent that of the entire industry, Fransen said. But GateHouse Media identified midwives in Florida, Washington, Arizona, California, Ohio, Wisconsin and Utah who unlawfully used drugs and devices as part of their practices. Two midwives in Oklahoma also told reporters they administer medicinal drugs without prescriptions.

Among the most dangerous procedures midwives handle is a vaginal birth after cesarean section, or VBAC. Its risk of uterine rupture can be fatal.

“I have seen women in the hospital break open their uterus and have to run them to the OR — and just seeing the blood and the baby in the abdomen — it’s terrifying and scary,” said Monica Tschirhart, an Oklahoma-based obstetrician-gynecologist. “I would not recommend it.”

But some midwives can’t make a living if they reject VBACs, said former certified nurse midwife Linda Johnson, who ran a freestanding birth center in Michigan for 14 years. It’s the bread and butter of their paycheck.

Gia McGinley wanted a VBAC for her third child. The 39-year-old actress found a certified nurse midwife, Sadie Moss Jones, who agreed to oversee the vaginal delivery at McGinley’s home in New York in September 2011.

But McGinley’s uterus ripped as she labored, and she passed out on her bathroom floor. Her husband, Charlie Romanelli, was in the kitchen getting ice water for everyone when he heard the midwife’s assistant scream for him to call 911.

Paramedics rushed McGinley to the hospital, and doctors delivered her baby by C-section. He was already dead. McGinley died a few hours later.

“She never saw Samson,” Romanelli said of his infant son. “I did. He was this little perfect baby. Everything was fine with him except he was dead.”

Romanelli sued Jones but dropped the case against her when she filed for bankruptcy in 2016, court records show. He also sued Keith Lescale, a physician he claims green-lighted McGinley’s home VBAC despite additional risks, like the baby’s large size — nearly 11 pounds. Both Jones and Lescale denied liability.

Lescale admitted he didn’t advise McGinley against the home birth because he wasn’t her primary provider and it was not his responsibility to do so, court records D show. But he claims to have told Jones to “proceed with caution.” Jones said she relayed the concerns to McGinley and told her to deliver in a hospital, but McGinley refused.

Romanelli disputed this, saying no one explained the risks and, had they known, they would have made a different decision.

After more than five years in court, the case was dismissed by state Supreme Court Judge Paul I. Marx, who blamed McGinley for what happened.

“This case is indeed a tragedy,” Marx opined in the 2017 decision. “More so, because Ms. McGinley might have spared herself and her unborn son an untimely death had she not been so intent on achieving the experience of vaginal birth.”

Romanelli said the decision crushed him.

“The people who suffer are me and my boys,” Romanelli said. “They don’t have a mom. They were 2 years and 9 months old when she died, and they have no memories of her. That’s terrible. Think about that.”

In the United States, the title “midwife” can mean something very different depending on the practitioner and the state in which she practices.

Not all states consistently regulate midwifery — some allow anyone to practice regardless of their educational background and without any oversight; others restrict the trade to nurse midwives only.

Beyond the regulatory differences, U.S. midwives lack consistent educational and practical standards. Unlike Canada, where all midwives must have bachelor’s degrees in midwifery and hospital privileges, the United States has no such uniformity.

Midwives here go by an alphabet soup of acronyms and titles. Each sounds important, even though some are essentially meaningless.

There's a difference in education, experience and clinical backgrounds required for different types of midwives — but the jargon differentiating them can be confusing.

Here's a breakdown of each type of midwife and their minimum qualifications.

Five Types of Midwives

Minimum

Qualifications

Traditional*

Certified

(Click for details)

Certified

Nurse

Certified

Professional

Licensed†

Minimum

Qualifications

Five Types of Midwives

Traditional*

Certified

(Click for details)

Certified

Nurse

Certified

Professional

Licensed†

- Pass the NCLEX-RN exam

- Get a state license

- These programs are accredited by the Accreditation Commission for Midwifery Education (ACME)

- About 40 universities offer the degree

- Options include Baylor University College of Nursing, Columbia University School of Nursing and Ohio State University College of Nursing

- Complete a Bachelor of Science in Nursing (BSN)

- Some Certified Nurse Midwife programs will accept Registered Nurses without a BSN working toward their midwifery graduate degree and provide a dual-degree

- Certified Midwife programs also require specific health and science courses

- Certified Nurse Midwives and Certified Midwives must pass the American Midwifery Certification Board (AMCB) examination

- Certified Professional Midwives must pass the North American Registry of Midwives (NARM) examination

- These programs are accredited by the Midwifery Education Accreditation Council (MEAC)

- About a dozen institutions offer the program

- Options include Bastyr University, Maternidad La Luz and Florida School of Traditional Midwifery

- Apprenticeships are approved by the North American Registry of Midwives (NARM) through a portfolio review

Sources: American College of Nurse-Midwives; National Council of State Boards of Nursing; North American Registry of Midwives; Comparison of Certified Nurse-Midwives, Certified Midwives, Certified Professional Midwives Clarifying the Distinctions Among Professional Midwifery Credentials in the U.S.

Traditional midwives might also be called community, lay or granny midwives. While these terms typically mean a midwife does not have a license, certification or a formal education sometimes a midwife with those qualifications will still use one of the terms.

Refers to state licensed, non-nurse midwives. Some states require a certification before issuing a license but others don't.

At the top of the pecking order are certified nurse midwives, or CNMs. These advanced practice registered nurses have bachelor’s degrees in science and a master’s or doctorate degree in nurse midwifery from one of several universities. They also must pass an exam by the American Midwifery Certification Board.

Some 11,825 CNMs practice in the United States, according to the American College of Nurse-Midwives. But few attend home births — of the more than 3 million babies they delivered in the past decade, 95 percent were in the hospital.

Non-nurse midwives dominate the out-of-hospital birth industry. Yet babies born under their care are nearly twice as likely to die as those delivered by nurse midwives, according to a GateHouse Media analysis of CDC data.

“There is a literal chasm between a medically trained hospital-setting nurse midwife and the other midwives who get their degrees from Google University,” said Fransen, the former South Carolina midwife. “There is a whole propaganda to make people believe we’re all the same. We’re not.”

Several kinds of non-nurse midwives exist — certified midwife, certified professional midwife, licensed midwife, traditional midwife — each varying in educational requirements and competence.

The most rigorously trained are certified midwives, who have health-related backgrounds and graduate degrees — and who must pass the same test as nurse midwives — but are not nurses. About 100 practice in the United States.

Most out-of-hospital midwives are certified professional midwives, or CPMs. They require no nursing experience, health-related background, bachelor’s or graduate degree. They can obtain certification by attending an accredited or non-accredited midwifery school — or apprenticing under another midwife — and passing a written test by the North American Registry of Midwives.

There are roughly 2,200 active CPMs in the United States, according to NARM. Many also hold state licenses, but hundreds live D where non-nurse midwifery is unregulated or banned.

In some states, like Oregon, it’s legal to practice with no formal training at all. Traditional midwives — also called granny midwives or community midwives — generally learn the craft through informal apprenticeship without requirements for education or credentials.

“One of the great burdens for our profession is that different people use the same word to describe themselves,” said Kate McHugh, a certified nurse midwife and director of global outreach for the American College of Nurse-Midwives. “We don’t have standardization for what it means to be called a midwife in the United States.”

There are also doulas. But they are not midwives, as they do not deliver babies and cannot oversee out-of-hospital births. They serve as assistants and provide emotional support. They are not referenced in the laws nor are they included in the statistics.

Many mothers told GateHouse Media they did not understand the distinction among the different types of midwives and assumed all were alike.

“We honestly thought she was a certified nurse midwife,” said Ohio mother Bambi Chapman, whose daughter died hours after a 2008 home birth. “We didn’t realize she was just a CPM. Knowing what I know now, I think that would have made a difference.”

Across the country, midwives keep practicing after fatal out-of-hospital outcomes while mothers take the blame.

Regulatory bodies can’t discipline midwives without knowledge of wrongdoing. But not all families complain. Some stand by their midwives. Some blame themselves. Some don’t know they can file a grievance.

Other women remain silent for fear of betraying the “sisterhood.” Mothers who opt for a home birth become a part of a community some describe as cultlike. Together they shun the patriarchal system of hospital births at all costs, even death.

“For some women, the experience of death is not the worst thing that can happen,” said Karen Baker, the California midwife. “It’s part of the natural process.”

When they do speak out, families risk the backlash of these midwives and their advocates. It’s a strategy employed across the country and detailed in an online survival guide for accused midwives called “From Calling to Courtroom.” The guide encourages midwives to turn clients into allies who rally at the first whiff of legal woes.

Women have lost friends, been harassed and received cease-and-desist letters after complaining about poor care and bad outcomes. Two women declined to be interviewed for this story, fearing further harassment from the midwifery community.

“There is a sisterhood,” said Linda Johnson, the former Michigan certified nurse midwife. “You just don’t criticize other midwives.”

Florida mother Stephanie Cudnik was attacked online after complaining about her licensed midwife, Amy Reynolds. Reynolds paralyzed her son’s arm by yanking and twisting his head to deliver him during a 2015 water birth at a freestanding birth center, according to a lawsuit D the family filed.

Cudnik said people were fiercely defensive of the midwife; some even blamed her for her baby’s injury W.

Reynolds, who is also a CPM, declined to discuss the case, citing patient privacy. The lawsuit was dropped in August after Reynolds admitted in an affadavit D she lacked state-required liability insurance at the time of the delivery.

“People are afraid to speak up,” Cudnik said, “because they know the backlash is so bad.”

New York mother Morgan Dunbar also was blamed for her baby’s death after an attempted home birth in August 2016 when she was nearly two weeks past her due date.

The first-time mom actively labored for six hours before begging her midwife, Eileen Stewart, to go the hospital. She was running a fever, her cervix was inflamed and the contractions were unbearable. She wanted a C-section, according to a complaint Dunbar filed afterward with the state.

But when they got to the hospital, a midwife-friendly obstetrician, Katharine Morrison, did not immediately perform a C-section despite bloodwork showing Dunbar’s white blood cell count was nearly three times the normal range, medical records show. High white blood cell counts are an indication of infection.

Morrison let Dunbar labor 12 more hours until the baby’s heart rate dropped and she ordered an emergency C-section.

It was too late. Baby Kali Ra Iman suffered catastrophic brain damage. The family removed him from life support four days later and held a transition ceremony to facilitate his journey to the next world.

Click image to hear Morgan Dunbar's own words

“We sang and prayed as we held his fading body until his breath was no more,” Dunbar said. “I anointed his tiny lips with raw honey. We then placed charged crystals and black-eyed Susans all around his perfect little vessel.”

Morrison declined to comment. But Stewart blamed Dunbar for the deadly outcome, saying Dunbar ignored her warnings about laboring in a hot tub. Stewart said she believes bacteria from the tub caused Dunbar’s infection, which compromised the baby.

“I was only involved with Morgan in what she asked me to do, which was to facilitate a home water birth for her,” said Stewart, who is both a CNM and CPM. “I feel very loving and healing thoughts around Morgan. But she will not accept responsibility for what she chose to do around the labor of her baby.”

Dunbar disputes any warnings about the hot tub and said Stewart personally approved it for labor.

“It’s total victim blaming,” Dunbar said. “And that’s almost worse than the death of my precious son.”

Dunbar filed a complaint with the state in 2017. The case is still open, she said. The state would neither confirm nor deny this. She also tried to sue, but no one would take her case, because New York’s laws make it difficult to seek justice after certain types of childbirth-related negligence.

Another family did sue the pair after a different infant died in 2014. Morrison and Stewart denied liability and settled, court records show D.

Midwives are trained to deflect responsibility, said Leigh Fransen, the former South Carolina midwife who took a class on the subject in midwifery school.

“Part of the Loss and Grieving course was coaching us on how to counsel the parents in such a way that they would understand it wasn’t our fault,” Fransen said in a Facebook post. “This was considered a necessity to be sure we were not sued.”

But it leaves women feeling helpless, Dunbar said. One of her friends committed suicide this year after failing to get justice for the death of her home-birthed son. The woman’s family declined to comment. GateHouse Media is not naming her.

“People throughout history have had terrible things happen having babies,” said Martha Reilly, chief of women’s and children’s services at McKenzie-Willamette Medical Center near Eugene, Oregon.

“Midwives peddle this idea that thoughts and feelings can lead to a better delivery,” Reilly said. “But when things go wrong, they go spectacularly wrong, and you have a lifetime of misery to follow.”

Up next: The Midwife

How she crossed statelines after a plea deal and kept practicing

© Gannett Co., Inc. 2018. All Rights Reserved.