Hear an audio version of this story.

Erie's Liberty Loan parade on Sept. 29, 1918, was the "longest and greatest" parade ever held in the city.

"A solid mass of humanity" marched to inspire people to buy bonds to help bankroll World War I. Soldiers and sailors home on furlough had a place of honor in the parade.

Bands from Erie, Corry and Meadville led the parade's 10 divisions. An estimated 20,000 marchers represented every school, civic club, service and industry in the city, and many in Erie County.

American Brake Shoe and Foundry, a munitions plant at West 12th Street and Greengarden Road, alone provided 7,000 employees for the parade.

About 50,000 people lined city streets to watch the procession. Two hours after the first units, the final units passed City Hall, where Erie Mayor Miles Kitts, Meadville Mayor E.W. Lawrence and other dignitaries watched from the steps.

Corry Mayor C.L. Alexander marched in the parade at the head of a Corry band.

"Practically every resident of the city and a majority of inhabitants of the county gave over their entire (Sunday) afternoon" to the event, according to the Erie Dispatch newspaper. The Dispatch and Erie Daily Times reported extensively on the event.

The parade was awe-inspiring, according to their accounts.

It would also prove deadly.

Within a week there were 250 cases of Spanish influenza reported in Erie.

The influenza epidemic that started in spring 1918 in the western United States and Europe by fall was raging across the country and worldwide when Erie's Liberty Loan parade brought tens of thousands of people downtown, where even one person infected with the virus could pass it on to hundreds through a cough, a sneeze or spit.

By the end of October, thousands of Erie residents were ill and more than 100 were dead, according to reports to the city Board of Health. By Christmas Day, the death toll topped 500.

The contagion, "once given a start, spreads like wildfire," said Dr. John W. Wright, chief of the Erie Board of Health in 1918.

'And in flew Enza'

The 1918-19 flu pandemic killed between 50 million and 100 million people worldwide, more than the Bubonic Plague and World War I combined, according to the Centers for Disease Control.

The war gave the virus wings. Soldiers on crowded military bases and troop ships were hit especially hard and helped spread the contagion. Young adults in the prime of life were prime targets.

Deaths from what became known as Spanish flu and complications including pneumonia weren't easy. Victims struggled for air and suffocated on fluids that built up in their lungs.

No one was safe from the virus, as a children's rhyme of the time made clear:

"I had a little bird, its name was Enza. I opened the window, and in flew Enza."

Why the 'Spanish' flu?

The "Spanish" influenza is believed to have gotten its name because Spain was the only major western nation whose newspapers widely reported on the flu and flu deaths beginning in spring 1918.

European and North American nations fighting World War I were reluctant to share details of the illness for fear of tipping off the enemy to depleted troop strengths.

-- Valerie Myers

The fight: Bans and arrests

On Oct. 3, Erie newspapers reported that the virus had reached Erie. Two people were sick.

One recently had returned from Massachusetts, the other from the Navy's Great Lakes Training Center in Illinois, both areas where influenza was raging.

It was raging, too, in Philadelphia, and Pennsylvania Health Commissioner Benjamin Franklin Royer ordered theaters, dance halls, saloons and other "public amusements" statewide to close Oct. 5.

"People went to bed last night as usual and woke up this morning to find that their amusements were entirely taken away from them," the Erie Daily Times reported that day.

Royer left it up to local health boards to decide if schools and churches also would close. In Erie, Wright signed the order.

He also ordered streetcars in the city of nearly 110,000 residents to be cleaned daily and directed the fire department to hose down State Street daily "in the hope of washing some of the germs away."

Retailers were warned against bargain sales and window displays that might attract crowds.

The public was warned against congregating on street corners. Police were directed to cite or arrest "corner loafers" and anyone spitting on the streets or sidewalks.

"It is known that one person in a crowded place can infect hundreds of others," Wright said.

Wright also ordered police to crack down on saloons that ignored the gathering ban and were doing "land office business" through side doors. Proprietors who were caught were subject to a $100 fine, 30 days in jail or both.

In spite of the precautions and penalties, the flu spread, reaching epidemic proportions by Oct. 13 when 500 new cases were reported in "the 16th District Epidemic Zone" including Erie, Crawford and Venango counties.

Wright, chief of the city Board of Health, had been appointed by the state days earlier to oversee the fight against influenza in all three counties and suspected that far more people were sick. He ordered the arrest of any physician who failed to report new cases.

He also ratcheted up efforts to contain the virus, prohibiting club and church "sick committees" from visiting the sick and prohibiting public funerals for flu victims.

Further, Wright said, "The body of a person who has died of epidemic influenza or pneumonia shall, under no circumstances, be taken into any church, chapel, public hall or public building."

The first two Erie flu deaths were reported Oct. 9. By the end of October, more than 3,000 Erie residents were sick with the flu.

Saint Vincent Hospital "borrowed" a nearby building from the Erie School District for overflow patients.

Hamot Hospital issued an urgent call for nurses; 16 of its staff 60 nurses were sick. Citywide, so many nurses were down with flu that "anyone who can take a pulse and read a thermometer" was urged to volunteer.

"It is as patriotic for a nurse to care for an influenza-stricken munitions worker as it is to care for a soldier in France," Hamot officials said.

Both hospitals were filled to capacity with flu patients.

Health officials raced to open an emergency hospital for flu victims on the second floor of the Elks Club at West Eighth and Peach streets. The federal government provided beds originally intended for workers at local munitions plants. City Council allocated $10,000, equivalent to almost $180,000 today, to help with costs.

The community did what it could for the patients. City housewives provided bedding. Church groups took turns providing meals. The Elks Club supplied flowers and reading materials for the stricken.

In Corry, where more than 1,000 people were ill and more than 200 died, the state armory on Washington Street was opened to patients.

Meadville Library housed 28 ill soldiers taken from troop trains.

The military school at Alliance College in Cambridge Springs was quarantined. Of the 250 soldiers and staff, as many as 70 were sick with the flu at one time. Five soldiers, a cook and an instructor died.

At the Erie County Courthouse, face masks provided free by the American Red Cross were "all the thing," according to the Dispatch. "All the girls in the (recorder's) office but one are wearing them."

General Electric set up a barracks for workers who became ill at its sprawling new plant in Lawrence Park.

Still, the virus spread.

By early November, Erie munitions plants reported that production was lagging; up to 30 percent of their workers were sick with the flu. General Electric, Erie Forge and American Brake Shoe employed an estimated 20,000 people between them at the time.

Hospitals were "jammed to the doors."

And post offices struggled to serve the public with 17 carriers down with flu at the main post office and six of 13 down in south Erie.

"It's difficult to keep the mail moving," Postmaster J.A. Hanley said.

A western official who "came East" to learn how to fight the flu was told, "When you get home, hunt up your woodworkers and set them to making coffins. Then take your street laborers and set them to digging graves."

By Nov. 10, just 41 days since the Liberty Loan parade, 181 Erie residents had died, and those who had escaped had become hardened to the daily death tolls, by then described as "only" a dozen or more a day.

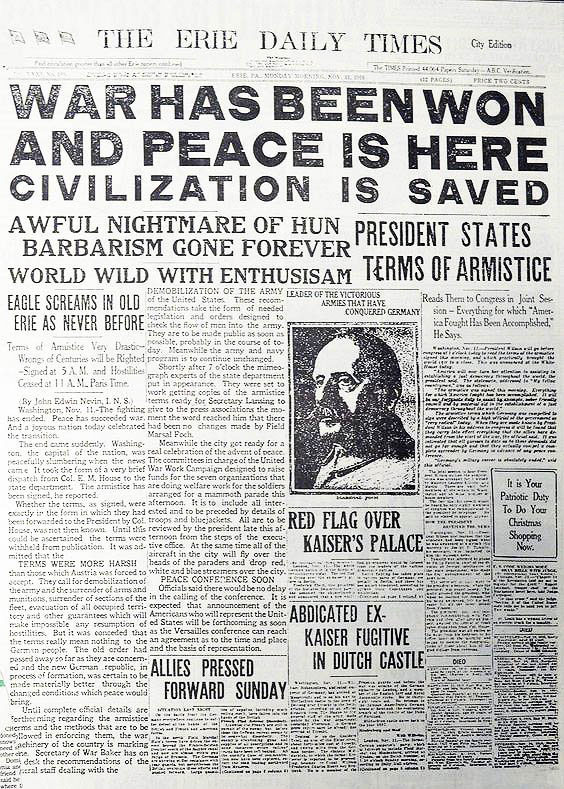

State and local health officials also might have become hardened to the numbers. When Royer informed local counterparts that they could lift the public gathering ban, Wright signed the order allowing schools, churches and most amusements to reopen Nov. 11.

Peace and resurgence

Nov. 11 also was the day that the armistice ending World War I was signed. Thousands of people celebrated downtown.

"State Street is full of excited throngs," the Erie Dispatch reported.

The number of flu deaths and infections in the city had slowly declined. Most people, including health officials, thought that the worst was over. Wright closed the emergency hospital Nov. 14.

That same day, flu numbers spiked again, to 214 new cases and five deaths in Erie in 24 hours.

"This big increase can be directly traced to exposure in the peace celebration early Monday morning and to overcrowding in the streets, in stores and in amusement houses," said Wright, who would later admit that he had closed the emergency hospital too soon.

The armistice celebration had rekindled the wildfire.

Saint Vincent and Hamot hospitals again filled to capacity within days. By Nov. 22, 259 Erie residents had died of influenza since early October.

Pushback: Dollars vs. lives

The death toll continued to rise. As it did, members of the public clamored for a new gathering ban.

Henri Chatain, of General Electric, asked the health board "if they could not do something to stop the influenza, which he believed to be far worse now than when the ban was on," according to the Erie Dispatch.

About a dozen General Electric workers were getting sick every day, Chatain said.

But health officials this time refused to impose a gathering ban, saying that it would only drag out the epidemic, which now "needed to run its course."

Local businessmen strongly opposed a new ban. It was the Christmas shopping season, "our season for making hay," J. Ross Teeter, manager of the downtown Palace Hardware, was quoted saying.

Led by downtown saloonkeeper R.P. Dailey, 200 local businessmen took matters into their own hands. They went to Erie County Court and on the day before Thanksgiving were granted an injunction against a gathering ban. Their filing claimed that a ban would be "unlawful, illegal and unnecessary" and would deprive them of the use of their property.

Retailers advertised Christmas and "peace" sales in both local newspapers.

Their actions fired up clergy, manufacturers and civic leaders who pushed back during a heated 2-hour Erie City Council meeting at the Commerce Building in early December. And though they put the businessmen on defense, City Council took no action to oppose the court injunction. Members instead endorsed a campaign to educate the public about influenza.

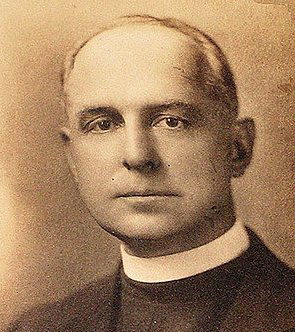

The Rev. A.R. Van Meter, dean of the Episcopal Cathedral of St. Paul, from the pulpit the next Sunday continued to press the city for action. In a blistering sermon, he called out Teeter and others by name for doing business as usual, epidemic or not.

"This is a contest between dollars and human lives," Van Meter said. "We are making laws a farce for the benefit of the saloons and the Christmas sales."

Influenza still was taking lives in the city.

Van Meter buried a 15-year-old member of his congregation the next day.

Also the day after his sermon, on Dec. 9, community women opened the General Pershing Emergency Orphanage in government-built housing for American Brake Shoe employees at West Fourth and Cascade streets. By Christmas, the orphanage housed 154 children whose parents had died.

In all, more than 500 Erie residents had succumbed to the plague since early October, Royer, of the state health board, said.

Over and 'impossibly' forgotten

Then finally, just before Christmas, the epidemic began to wane. Deaths here and there in the city continued into early 1919, but the worst was over — just as the city belatedly sent its solicitor to court Dec. 23 to try to overturn the businessmen's injunction.

By Christmas Day, the city was looking forward.

There were no more daily reports on flu cases and flu deaths in the newspapers, no more calls for nurses, no more orders from Dr. Wright.

News stories instead focused on when "the boys" would come home from the war, whether their jobs would be waiting for them and a seemingly never-ending series of "victory balls" and "victory sings" in Erie clubs and parks.

The Spanish flu was all but over and all but forgotten by everyone but those who lost loved ones.

"For me, that's the most mysterious thing about it," Alfred Crosby, author of the 1976 "America's Forgotten Pandemic: The Influenza of 1918," said in a 2008 interview with the Toronto Star.

"The vagaries of the virus, we'll understand them eventually. And we'll understand how flu epidemics work. But we're never going to understand: How the hell did we have something that killed millions and millions of people and then we said, 'Oh, well' and went on to the World Series or something?

"It's impossible. And yet it's true."

Valerie Myers can be reached at 878-1913 or by email. Follow her on Twitter at www.twitter.com/ETNmyers.