Hundreds of thousands of kids are going to school unvaccinated

This year’s back-to-school season coincides with the worst measles resurgence the nation has seen since the disease was declared eliminated nearly two decades ago.

At least 1,241 people — many of them school-aged children — have contracted the viral infection across 31 states so far this year, according to the latest count by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, which called it the highest number of reported cases in nearly a generation.

The rise comes amid increased demand for vaccine exemptions as parents, some dubious of government control or worried about the now-debunked link between immunization and autism, seek to opt their children out of the mandatory shot schedule.

Some states are starting to crack down on the exemptions in response to measles outbreaks; others are considering offering parents even more ways to opt out.

About 200,000 kindergarteners across the United States entered school without their measles vaccination in 2017, according to the latest CDC data available.

In seven states, the percentage of kindergarten students who are unvaccinated for measles is almost twice the national average of 5.9%, according to state figures compiled by the CDC.

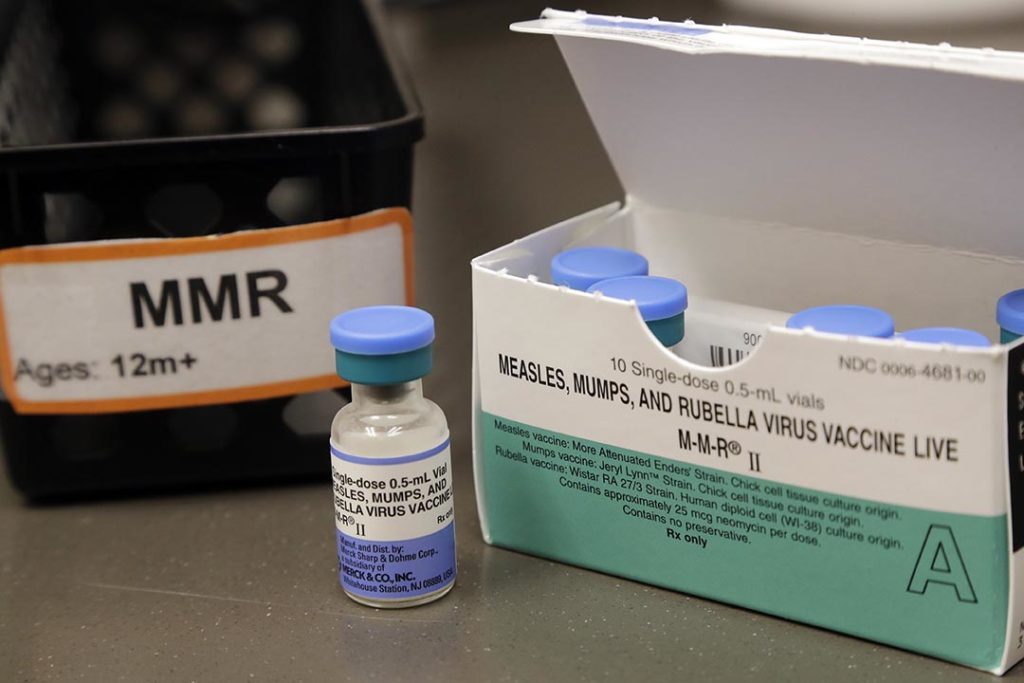

Colorado, Idaho, Washington, Alaska, Arkansas, New Hampshire and Kansas all reported that at least one in 10 kindergarten students had not received the vaccine for measles, mumps and rubella, commonly referred to as MMR.

But those broader figures can obscure pockets of low immunization rates where outbreaks can occur.

Even states with seemingly high vaccination rates may include individual schools where as many as a quarter of students are unvaccinated, according to data from states that make that information available, as well as academic research powered by public records.

“We used to always focus on making vaccines available and accessible throughout the community, so people weren’t unable to get their children vaccinated because of transportation issues or lack of insurance,” said Diane Peterson, associate director of the nonprofit Immunization Action Coalition.

“Now, a lot of that is probably equalized,” she said. “But what we find is that there are communities that are being swayed by anti-vaxxers. They are persuading parents there is possibly harm to come from vaccines” despite decades of medical research establishing their safety.

State laws vary

School vaccinations have long been a critical tool for combating infectious diseases like measles. Because most children attend a public or private school, most must be vaccinated under state laws.

That power was granted in 1905 by the U.S. Supreme Court, which ruled that states have the ability to protect the public from infectious diseases, even at the cost of personal freedom.

All states allow exemptions for children medically unable to receive vaccinations — a policy few, if any, public health official has challenged. But 45 states also allow exemptions for personal or religious beliefs, which experts believe have contributed to the rise in measles outbreaks.

Those differing state laws lead to the differences in state vaccination rates.

Take Texas, for example. Vaccine exemptions in that state grew 28-fold since a 2003 law making it easier for parents to opt out, according to a study published in August in the Journal of the American Medical Association.

The study showed how the rise in unvaccinated Texas school children heightens the risk for a major measles outbreak. Its computer simulations revealed that a single student with measles could start an outbreak infecting more than 400 people.

If more parents continue to seek the state waiver, the authors wrote, “the potential number of cases of measles outbreaks is estimated to increase exponentially.”

That’s why at least five of the nation’s largest professional groups for doctors, including the American College of Physicians, have supported eliminating or tightening exemptions.

“Allowing exemptions based on non-medical reasons poses a risk both to the unvaccinated person and to public health,” said then-ACP President Wayne J. Riley in a 2015 statement. “Intentionally unvaccinated individuals can pose a danger to the public, especially to individuals who cannot be vaccinated for medical reasons.”

Ten states this year considered bills to end non-medical exemptions for childhood vaccine requirements. Only New York and Maine approved the measures wholesale. Washington approved it just for the MMR vaccine.

California had ended its non-medical exemptions in 2015.

But several states this year considered doing the opposite. Of a combined 64 bills related to childhood vaccine requirements, 13 would have made it easier to receive an exemption and 21 would have required doctors or schools to provide parents with information about vaccine safety or perceived hazards. None passed.

The bills to loosen exemptions were introduced despite medical consensus that vaccines are safe and effective.

“The measles vaccine protects 97% of people. It’s amazing; few preventive measures work 97% of the time,” said Daniel Salmon, former vaccine safety director for the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services and current director of Johns Hopkins University’s Institute for Vaccine Safety.

Devastating effects

The spread of measles often starts among unvaccinated children, who then transmit the disease to other unvaccinated children, who then pass it on to someone else, Salmon said.

A high fever, cough, runny nose and watery eyes precede the disease’s iconic rash. Many people with measles also experience ear infections, which can cause permanent hearing loss.

Other serious complications include pneumonia and brain swelling. Some, particularly infants and people with compromised immune systems, can suffer permanent brain damage or die from lung or neurological complications.

People who contract measles do not develop symptoms until one or two weeks after they became infected, meaning they can unknowingly spread it to others before becoming ill themselves.

At risk are the 3% of the population for whom the vaccine fails, as well as those not vaccinated because they’re too young or have a compromised immune system or for some other reason. Those people, too, can spread the disease before anyone knows measles has entered the community.

If enough people are vaccinated, the disease struggles to spread beyond the initial person or family. That’s called “community immunity” or “herd immunity.”

“God forbid your child has leukemia and is going through chemotherapy,” Salmon said. “They can’t be vaccinated. If they get the disease, they are more likely than the average person to have serious complications or death. They are really dependent on everyone else to get the vaccine.

Salmon said the vaccination program’s success has, in part, fueled the disease’s return.

“People don’t fear the disease anymore because they aren’t familiar with it,” he said. “Then the vaccine is associated with something they do fear, like autism. Everybody knows someone with autism.”

Medical research has repeatedly shown the MMR vaccine does not cause autism, even though the disorder typically appears around the same time children receive that shot.

Vaccine fears are not new, but the internet has made it easier to spread misinformation and harder for parents to discern truth from fiction. As more parents forgo childhood shots, more kids join an unprotected cluster ripe to become ground zero for a broader community outbreak.

Outbreaks are defined as three or more linked cases and are most likely to start in groups with frequent contact — such as a school, family, youth sports team or church. When community immunity is compromised, measles can spread easily and rapidly.

That’s what researchers found in the Texas computer simulation study.

“Unfortunately, people who are unvaccinated tend to interact with one another more than with everybody else,” said David R. Sinclair, a University of Pittsburgh public health researcher who worked with the Texas Chapter of the American Academy of Pediatrics on the study.

But many of the people who contracted measles in the study’s simulations were not vaccine refusers.

“Looking at larger outbreaks of 25 people or more, we found that 64% of infections had been in students for whom the vaccination had been refused,” Sinclair said. “The remaining infections were happening in the rest of the population.”

“Anyone who makes a decision not to vaccinate their children based on personal or religious beliefs,” Sinclair said, “is making a decision that has implications for the wider community.”