Airlines give themselves more buffer time, GateHouse Media analysis shows.

The next time your pilot announces that you’ve landed early, check again.

Schedule padding — a common strategy among airlines trying to avoid unhappy customers — has grown over the past 10 years, according to a GateHouse Media analysis of U.S. Department of Transportation data.

That means airlines have been giving themselves more time to complete a flight and say that a plane landed early.

For decades, the U.S. Department of Transportation has tracked how long airlines say a flight will last — something called the “computer reservation system” time — and how long the flight actually lasts.

Take Delta’s flight from Lexington, Kentucky, to Atlanta. Twenty years ago, Delta typically scheduled this flight for 1 hour and 14 minutes from gate to gate and was usually about 2 minutes late.

These days, passengers sit on the plane about a dozen minutes longer. Yet the fight typically lands early. That’s because Delta increased the scheduled time to 1 hour and 29 minutes — 15 minutes longer than in 2003.

Or take a look at Alaska Airlines’ flight from Anchorage, Alaska, to Seattle, which 20 years ago was scheduled at about 3 hours and 18 minutes gate to gate. Statistics show the passengers usually landed about 1 minute late.

These days, the route takes roughly the same time — a minute longer on average. But passengers are arriving on average 6 minutes earlier than scheduled. That’s because last year Alaska Airlines increased the posted time to 3 hours and 27 minutes.

Experts disagree on whether the practice is clever manipulation or prudent planning.

Tufts University economics professor Silke Forbes researched the phenomenon last year after a flight from Cleveland to Washington D.C. landed 30 minutes early.

Forbes, who previously conducted research on flight delays, was skeptical that airlines were padding their schedules because of the associated costs. Doing so not only reduces the number of flights airlines can pack into a day, Forbes said, but it boosts personnel costs.

Yet when she and her colleagues dug in, they found that the gap between scheduled flight times and actual flight times was indeed growing.

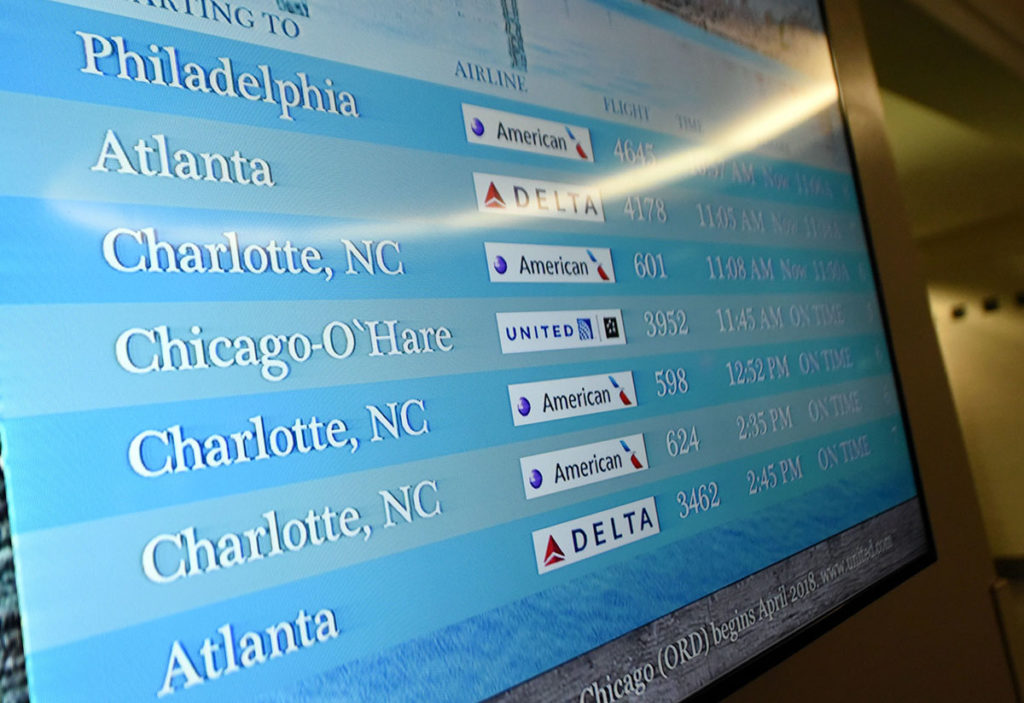

Check your flight:

Flights are taking longer overall because taxiing times have increased and pilots are flying slower to save fuel. But airlines are making sure to schedule even more additional time than they need, Forbes said. And over the past 10 to 15 years, the discrepancy has grown.

In addition, the researchers found that when smaller airlines like JetBlue padded their schedules, legacy carriers like American Airlines responded by adding more buffer time to their schedules to remain competitive.

“Over the last decade,” Forbes said, “airlines seem to care more about being on time.”

Pros and cons

How a consumer feels about the trend depends on what they value more — timeliness or time spent in the air. Someone trying to make a tight connection, for example, might appreciate arriving a few minutes early. But flyers who want to spend less time in the air might find schedule padding annoying, Forbes said.

That’s where Seattle resident Jega Vigneshwaran finds himself. A self-proclaimed aviation geek who logs each of his flights in a personal spreadsheet, Vigneshwaran noticed his trips to the Bay Area to visit family usually landed a half hour earlier than scheduled.

“If I’m flying for fun and I have someone picking me up on the other end, it’s a little frustrating because if I arrive 45 minutes early, I’m just waiting at the airport,” said Vigneshwaran, who is an engineer at Boeing.

“On the flip side, I would rather the airlines pad the time a little bit and get me there earlier or on time rather than trying to be aggressive and get me there late,” he added.

John Grant, a senior analyst with air travel intelligence company OAG, said airlines are doing their best to adapt to rising uncertainty from external factors affecting scheduling, including increased air traffic and more inclement weather due to climate change.

“The word ‘padding’ implies airlines are doing it to ensure they are operating punctually and to schedule,” Grant said. “To a degree that is absolutely true, but they’re having to do this because of the constraints that make it increasingly harder for them to maintain those schedules that they’ve previously had.”

The amount of padding is not a lot — airlines are giving themselves an extra 4 minutes of cushion compared with two decades ago, GateHouse Media’s analysis revealed. The measure is from gate to gate, taking into account time spent taxiing to and from the runway, as well as in the air.

Still, the effects can be dramatic.

Fifteen years ago, about 31% of routes took longer than their scheduled time. Now, fewer than 10% do.

But if you were to compare today’s flight times with the posted schedules from 15 years ago, 58% of routes would be considered late.

Among major airlines, Delta and Southwest build in the most buffer time, adding an average of more than 6 minutes across all their routes last year, according to GateHouse Media’s analysis.

Delta in particular began aggressively padding in the late ‘00s. Their on-time performance is also a key part of their public relations, according to Grant.

“It’s a clear marketing message,” he said.

Forbes said the practice means consumers should take any airline’s on-time performance proclamations with a grain of salt, comparing the situation to test takers who write their own questions and make them easier over time.

“We cannot fault (airlines) for wanting to look good,” Forbes said. “But what’s a bit misleading is this question of what does it mean to be ‘on time.’”