NOT FORGOTTEN: The Class of 2020

MetroWest and Milford area high school seniors had the last stretch of their school year yanked from them by an invisible menace. The coronavirus pandemic separated them from their friends and teachers, and stole their rites of passage. Proms were canceled, senior trips dismantled, and at many of our schools, the graduation ceremonies took on a different look.

The Class of 2020 started school just before the Great Recession enveloped our country and studied through the Boston Marathon bombing, all-to-common school shootings and a steadily improved economy that was stifled by the pandemic. Through it all this group of young adults persevered and achieved.

The Daily News spoke with 15 seniors who represent a cross-section of the Class of 2020. They include a young man trying to figure out what it means to be a man, a young woman who arrived in America four years ago with the goal of going to college (she made it), a young man who created his own clothing line, a young woman who had a baby in her sophomore year, turned her life around and graduated as a straight-A student, a transgender young man who is a YouTube influencer and wrestler, and a young woman who designed, manufactured and distributed personal protective equipment to hospitals and stores across the region.

Congratulations Class of 2020! We cannot wait to see how you change the world.

* * * *

Mira Donaldson

Framingham High School

Mira Donaldson at her home in Framingham. She will be attending Spelman College in Atlanta. John Walker | Daily News staff

Mira Donaldson graduates high school advocating for change

Graduation is often romanticized as the moment when children step into the world. It’s a time of excitement, a time to reflect on the society young adults are entering. The class of 2020, many of whom graduate this week, are entering a different space.

Graduating seniors are entering a time of civil unrest. Following the death of George Floyd on May 25, protests have consumed cities large and small in every state of the country, including Framingham and Boston. Derek Chauvin, the police officer who allegedly killed Floyd by kneeling on his neck, is facing a charge of second-degree murder, and three other officers have been charged with aiding and abetting second-degree murder and second-degree manslaughter.

Graduates like Mira Donaldson aren’t shying away from the moment. Donaldson, a recent graduate of Framingham High School, is trying to change the society the class of 2020 is graduating into. In high school, she created the Black Student Union, participated in the youth-city council and served as a board member on the MetroWest’s Youth in Philanthropy program, which aims to create MetroWest’s next generation of philanthropists and leaders.

. . . I really do want to change the world.

In the fall, she’ll attend Spelman College in Atlanta, a historically black college, and plans to major in political science and dance. She hopes to become a congresswoman or state senator someday.

“(Activism has) more gravitated toward me than anything,” Donaldson said. “I feel like every person of color feels like they have a responsibility to represent their people … but for people who really can’t be out there just remember that your existence is resistance.”

Donaldson attributed her interest in city government and activism in general, to her own experiences as a black woman. She remembers in grade school when classmates wouldn’t befriend her because she was black. It continued with the use of the N-word, as well as countless microaggressions through high school.

“I kind of felt very isolated in elementary school just because of the color of my skin sometimes,” Donaldson said. “When you’re that little, you should never feel that way.”

During high school a friend told Donaldson about their Black Student Union, a space in which black students shared their experiences within their own communities and discussed potential policy improvements. Donaldson founded the program at Framingham High School, with help from classmates, and served as the president through the end of her senior year.

The group met on Thursdays and was paired with Framingham School Committee member Gloria Pascual. A mother of three children, Pascual joined the committee after spending time as the only person of color at her children’s youth sports games. She shared these experiences with Donaldson and the other students when teaching them how to speak in front of groups of people.

“Mira is an amazing woman,” Pascual said. “She’s really extremely compassionate for humanity and really getting to hear everyone’s voices and how we still process our own feelings.”

Mira Donaldson, a Framingham High School senior, will be attending Spelman College in Atlanta. John Walker | Daily News staff

The Black Student Union’s policy suggestions garnered a variety of responses while working with Pascual. The BSU started an initiative to change Columbus Day to Indigenous People’s Day in the Framingham community but it was denied. Their movements to eliminate the N-word in their school community were more successful.

After a social media post from a Framingham High student used the racial slur, the BSU started a campaign to end the use of the word within the school. They compiled a video that features both students and faculty denouncing the racial slur and held a community meeting to discuss the context and repercussions behind the word’s usage.

Donaldson’s focus remains on education moving forward. She believes people need to better educate themselves on systematic racism through reading and alterations in academic curricula. She recommends books like “The Hate U Give” by Angie Thomas, which details the experience of witnessing a white police officer kill a black man, and “The Bluest eye” by Toni Morrison, which explores a black girl searching for blue eyes to find a semblance of “whiteness.” Both books, Donaldson noted, help white readers shed light on injustices that impact her daily.

“There’s a lot of cases of disenfranchisement within your local town,” Donaldson said. “So I feel like once people realize that we can start from the bottom to the top and really work on a national level once you start looking at your own city and your own town.”

The Class of 2020, known as Generation Z, is different than generations past, Donaldson said. She believes her classmates are more humble. Rather than emphasizing a “power trip” in politics, she believes her class will focus on their experiences to influence their political beliefs and social activist movements.

Donaldson emphasized the change doesn’t necessarily start with national politics. It can start locally, like in the avenues she’s sought out so far. A bottom up approach is a stepping stone for something bigger, she said. With a few years at Spelman, Donaldson, too, may reach for more.

Spelman’s motto reads: “A choice to change the world.”

“I felt like that really spoke to me,” Donaldson said. “Because I really do want to change the world.”

* * * *

alexis cumminsky-mclaughlin

Marlborough High School

Marlborough High graduate Alexis Cumminsky-McLaughlin and her son, Justin, 2. John Walker | Daily News staff

‘360 turnaround’: how motherhood changed a Marlborough graduate’s life

Alexis Cumminsky-McLaughlin has a rule when she brings her 2-year-old son, Justin, to a store. She’ll only buy him a toy if he’s picked up after himself. Only if he’s used the potty right. It’s a rule she didn’t grow up with, but enforces now more than ever.

If Justin wants a toy, he has to earn it.

Growing up, Cumminsky-McLaughlin, now 18, would walk into Toys R Us and get any toy she wanted. She would run from shelf to shelf, picking out dolls and their makeshift homes. Her upbringing lacked direction, with a history of abuse within parts of her family. But as a child, she had free rein, picking out her favorite toy each time.

“Discipline,” she said of the reasoning for her rule. “I didn’t have any of that.”

On June 6, Cumminsky-McLaughlin graduated from Marlborough High School, a straight-A senior in the school she was kicked out of as a freshman. She’ll complete her EMT training from the department that knew of her differently four years ago. She completed an internship at the Marlborough Police Department, working alongside officers she said she knew from encounters at her house.

She’s raising a son who helped give her direction, the same direction she’s trying to instill in him.

“People who thought she couldn’t do it, she proved them wrong,” said her mother, Kassie McLaughlin. “She can do that really well.”

Alexis Cumminsky-McLaughlin with her mask. John Walker | Daily News staff

Marlborough’s Alexis Cumminsky-McLaughlin plays on a slide with her son, Justin, 2. John Walker | Daily News staff

Cumminsky-McLaughlin, described as boisterous, strong-willed and protective of loved ones, was never someone who would back down from other people. Along with her mentors, she agreed if someone comes after her, she’ll fight right back. She agreed that she’s all of those things. But there’s a side to her that not everyone knows, where she’ll use her strong-will to stand up for other people. If she sees a stranger crying in the hallway she’ll go up to them. After school she spent time in the special education room, giving students extra help when kids needed it.

“I want people to feel loved,” said Cumminsky-McLaughlin. “I want people to feel like they should be living.”

Her mother knows that from when she was little. Her daughter would confront older kids when a neighbor was getting bullied. Her EMT instructor, Brandy DeBarge, knows that from the way she asked early to go on ride-alongs. She wasn’t afraid of the split-second decisions EMT workers face with every call. Steven Bishop, assistant principal at Marlborough High School, knows that from their meetings together and how her mindset changed over the past four years.

“A 360 turnaround,” was how he described it, and four years ago, Bishop knew Cumminsky-McLaughlin for a different reason.

Her name first came up in a discussion he had leading into the 2016-17 school year. On the phone with another vice principal from Charles Whitcomb Middle School, he heard about a student who struggled in a school environment, he said. “Academic and disciplinary issues,” he heard, and the following school year, it wasn’t long before those kicked in.

Discipline… I didn’t have any of that.

About two weeks into the school year Cumminsky-McLaughlin had her first fist fight, she said, and in less than five months she was sent to Hildreth School, an alternative high school in Marlborough. She wouldn’t always fit in she said, and as a result she became defensive, untrusting.

“People would say the smallest thing to me,” Cumminsky-McLaughlin remembers from freshman year. “And I’d be like ‘I’m gonna f*** you up.”

A wake-up call came in March of her sophomore year at the Hildreth School, in a message from her doctor, saying she was pregnant. The following week Cumminsky-McLaughlin skipped school, not knowing if she would ever go back and afraid to tell anybody what happened. Her mother wept after hearing the news and offered advice. Cumminsky-McLaughlin soon realized that the advice wasn’t meant to insult her, but to help her. She let more people in.

Two years later, it’s not the fights – which Bishop said he isn’t authorized to speak about in detail – or the times when he pulled her into his office that stick out to him. It was a conversation two years later, days after she was admitted back to Marlborough High School, just months after Justin was born, when her wake-up call was still setting in.

“She was like ‘I’ve gotta figure it out now. I have to get an education and move on with my life. And I’m not getting wrapped up in all the drama that was holding me down,’” Bishop remembers from the conversation. “So she really realized the things that were holding her back, and that’s’ the biggest tell-tale sign.

There are other moments that stick out to Bishop, too. Regular conversations in his office just to check in. Seeing a new sense of maturity in her junior year, nearly two years after she was sent away. Cumminsky-McLaughlin caring about her role as a mother, a student, an EMT trainee, and balancing them all.

There she was, in a rigorous EMT training course, asking for extra assignments and to ride along in an ambulance. There she was in C-period, getting support on math assignments so she could finish them before school ended. There she was in the evening, raising Justin with her boyfriend, making him earn his toys.

“You go to a classroom and a teacher says ‘does anyone have any questions?’ And really nobody really understands what’s going on,” said Bishop. “She’s going to be the first one to say ‘hey, I have no idea what we’re talking about right now.’ So she’s learned some of those leadership skills, which I really think is to serve her, but I don’t think she realizes she’s serving other students as well. Because she spoke up when others wouldn’t.”

Marlborough High graduate Alexis Cumminsky-McLaughlin will be studying at Quinsigamond Community College in the fall.

Cumminsky-McLaughlin wants to be a special education teacher, an EMT and a police officer. She’ll attend Quinsigamond Community College and plans to earn an associate degree by 2022 in special education and criminology. Then she’ll study at Boston College, where she has already been accepted, and plans to graduate by 2026.

Still, she’s the same person she was four years ago. She has the same boisterous voice. She sticks up for the people she cares about, her mother, her son and her boyfriend. She has the same strong-will, but more motivation.

On May 30, she sat outside in the sun with her mother and reflected on the past four years. Her graduation was in eight days, now online. Kassie McLaughlin wanted to buy a plywood stage outside, and cover it with a red rug for her daughter,

“It’s like a four-year journey for her, how she got to this place,” said Bishop. “This kid’s a dark horse. In Vegas she’s a-million-to-one odds. And she beat the odds.”

* * * *

Angelo Venuto

Lincoln-Sudbury Regional High School

Lincoln-Sudbury graduate Angelo Venuto will be attending Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute in Troy, NY. John Walker | Daily News staff

Injury gives Lincoln-Sudbury senior new perspective on life

Angelo Venuto is trying to keep his mind busy, so instead of waking up at 8:30 a.m, he rises four hours earlier, walks to Tippling Rock in Sudbury and starts hiking. He climbs to the top where it’s often just him and a 28-year-old man he’s taken a liking to.

He doesn’t know the man’s full name – just knows him as Patrick, the friendly stranger who sees the more contemplative Angelo Venuto. The 17-year-old who arrives at 5 a.m., watches the sky switch shades and tries to clear his mind of what’s happened these past few months.

Venuto is better known as the faceoff specialist on the lacrosse team. The “bullish” left winger on the hockey team who can take a hit then give one. The Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute lacrosse commit who sometimes “speaks before he thinks,” asks questions in class that “makes for good content,” and owns that reputation.

“People probably say I’m a clown,” he said.

And then there’s the kid that Patrick knows, who takes a picture of the sky each morning because “every cloud formation is different.” The one who watched “The Longest Ride” and related not to Luke Collins, the young bull-riding protagonist, but to Ira Levinson, a 91-year-old man reminiscing about a past relationship. The one who can talk about alternate universes for hours and writes in his journal about high school, how the culture he thrived in has got adulthood and masculinity all wrong.

“It bothers me that I can’t bring these two worlds together,” said Venuto.

In his junior year, an illegal hit in a hockey game tore Venuto’s ACL, ending the season early and his lacrosse season before it started. Last year, for the first time, Venuto didn’t have what had shaped who he was to that point, what everybody else knew him for, his athletic ability, and the confidence that came with it.

“I was very nervous my life wasn’t going to be what it was again,” he said. “I was also very hopeful.”

Lincoln-Sudbury’s Angelo Venuto gets between Westford Academy defenders during a game in Westford in 2018. John Walker | Daily News staff

Lincoln-Sudbury senior Angelo Venuto controls the puck during the Division 2 North championship game against Triton at Tsongas Arena in Lowell, March 9, 2020. The just days later, the coronavirus pandemic would end the Warriors playoff run. John Walker | Daily News staff

Venuto felt a sense of deja vu in March, when Gov. Charlie Baker announced students would leave physical classrooms and go online, putting him in a familiar situation – a hockey season shortened, a lacrosse season lost.

The announcement came less than a week before the state championship hockey game between Lincoln-Sudbury and Canton. The disappointment returned him to last year, he said, because much of it felt – and still feels – the same.

The scars from Angelo Venuto’s anterior cruciate ligament repair surgery are still visible on his left knee. He’s a lacrosse commit to Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute in Troy, NY. John Walker | Daily News staff

In the weeks after he tore his ACL he came home angry, he said, arguing with his parents and asking the same series of questions. “Why me?” He would come home from physical therapy, frustrated from the slow progress, frustrated as he watched the lacrosse team from the sidelines.

Soon, though, with rehab as his only form of physical activity, Venuto submitted to his parents’ advice: “Let it go.” He soon found passion away from the ice — church every week — even if he went alone. He found it in the journal in which he wrote, even if nobody else read it. He discovered a sense of masculinity that centered around relationships rather than athletic ability, even though not everyone his age saw it that way.

“I think if it’s two identities – which is a little strong to say – I think he’s very much aware of those two,” said Kevin Fowler, a friend and mentor Venuto met at a church retreat. “And he’s trying to intertwine the both of them.”

But in other ways, the past few months have been much worse. There’s no senior spring, prom or in-person graduation. His mother contracted coronavirus and was bed-ridden for parts of March and April. His grandmother later contracted it and died in a Framingham nursing home. She was 91.

All he has now is time and his new mindset, so up the hill he goes, looking for the small victories over the past few months. More time with his family, more time to reflect, and more time to think about more pressing questions. “What worked for me in high school?” he’ll ask himself. “What didn’t work in high school?”

“Now you’re sitting, no one’s judging you,” said Venuto who, months later, still hikes on occasion. “And you really can do some pros and cons of your life.”

* * * *

Instead of players choosing their numbers, Lincoln-Sudbury Lacrosse Coach Brian Vona has a different method for assigning jerseys. Players wear the numbers of alumni whom they’re reminiscent of. In his sophomore year, Venuto got number 25, along with a hand-written note from the player who had worn that number 14 years earlier – Jeremy Kolb, a veteran in his early 30s who lives in Greensboro, North Carolina.

The two started to text frequently, a quick introduction that soon turned into the two sending motivational quotes, similarities about their lives and later, Bible verses.

“He hadn’t been jaded by the world yet,” said Kolb of their first interactions. “And I think he just brought this energy and excitement.”

Later that year, Kolb traveled from Greensboro to watch Venuto play, the then-15-year-old had one goal for the trip: impress Kolb with his athletic ability. When Venuto scored a goal against Wayland, he scanned the crowd for the other number 25.

I think at first he wasn’t confident in the other side of himself.

During his junior year, though, when Venuto couldn’t play, Kolb again made the trip to Sudbury. But what was there to prove? That goal against Wayland would end up being the last of his high school career.

“I think at first he wasn’t confident in the other side of himself,” said Kolb. “Because he was kind of afraid of it, because he didn’t want to be – I don’t know, it’s hard. (So) I tried to show him how I’m vulnerable.”

Kolb played lacrosse briefly in college, he said, but he also played dungeons and dragons. He was a veteran, but also developed an interest in accounting.

Soon, Kolb saw who Venuto was becoming. The injured lacrosse player who wrote “beautiful journal entries.” The former top scorer on the hockey team who also found solace in church retreats.

One of those church retreats was in July, a few months after Venuto said frustration from the injury turned to self-reflection. Venuto saw a man in his late 40s sitting in a room full of hundreds of people. He knew him as the chaperone for the boys on the trip, that he seemed “down-to-earth.” He walked up to Kevin Fowler, a salesman in his late 40s. “Can we meet?” he asked.

Venuto calls it a mentorship, Fowler calls it a friendship, but either way, one year later, they sit at Emma’s Cafe in Stow every Sunday morning (before the pandemic). They’ll talk about “day-to-day” happenings and sometimes discuss his relationships, the ones that Venuto says now define “manhood.”

How Venuto was hungry to get back on the field but how the time away opened his attitude up more. How he was beginning to learn what love is – how it feels awkward for high school boys to talk about that – and how he had trouble expressing that in all of his settings.

“I think in a way he struggles with that, but I don’t mean that as a bad thing,” said Fowler. “He’s just learning.”

Lincoln-Sudbury graduate Angelo Venuto wears his 2020 State champion cap. John Walker | Daily News staff

* * * *

In late March, a worried Venuto had trouble sleeping. His mom could hardly move out of bed and had trouble breathing a few weeks after her symptoms for coronavirus started.

Venuto thought back to how his mother was there for him when he was injured, and how her guidance slowly turned his mindset around.

Let it go.

Venuto picked up his phone and sent out a request to over 40 different friends.

And soon, he made a nine-minute video of friends and family telling her that they’re thinking of her. That was the “discerning leader” that Kolb saw and the kid that Patrick sees every now and then at Tippling Rock.

“Seventeen-year-old boys don’t do that,” said Fowler. “And he did it. He thought about doing it and he did it.”

Those are the things Venuto has found he can control, not what happens but how he responds. Not the circumstances he’s given but how he processes it.

And there are other things he can’t control, one of which happened about a month later. His grandmother contracted coronavirus, and he got a call in the early morning of April 25 that she had died. With no games to prepare for and nothing but time on his hands, he wanted to put his thoughts down in his journal.

“I got the call at 3 a.m,” said Venuto. “And I went up to Tippling Rock at 4 a.m. and saw the best sunrise ever.”

* * * *

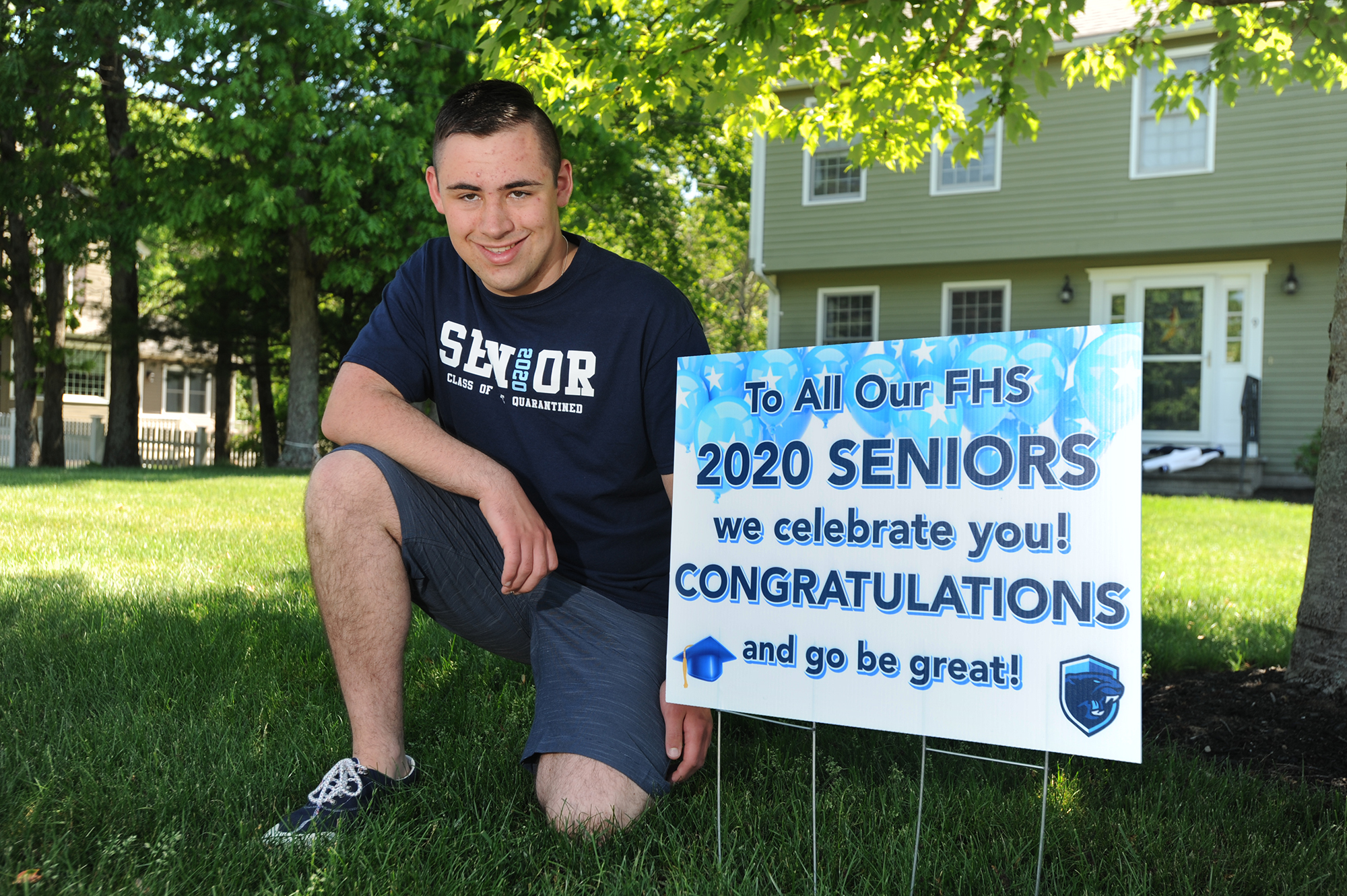

Declan lynch

Franklin High School

Declan Lynch with his scholarship to Dean College. Art Illman | Daily News staff

Franklin’s Declan Lynch has the ‘grit’ to surmount obstacles

Beth Raffin always meets with her eighth-grade students to discuss their plans. Some talk about high school or college. Some express their interests in driving or applying for their first job. For many eighth graders, this is an exciting concept, a discussion about the array of opportunities awaiting them.

The world of the unknown didn’t have the same appeal for Declan Lynch. He was scared of driving and not confident in his abilities. He feared reading street signs and traffic signals. He wasn’t sure about high school, let alone applying for college.

Lynch expressed all this during his meeting with Raffin, a special education teacher, to discuss his individualized educational program, otherwise known as an IEP. Throughout his life Lynch, 18, has struggled with communication, leading to a challenging educational experience. His IEP lists his primary disability as communication and secondary disability as emotional, which led to lash-outs in the classroom and erratic erase marks on papers. But it never prevented a learning experience and resumé that matches his classmates: a high school diploma, several scholarships and plans to attend Dean College in the fall.

“There couldn’t be a better success story,” Raffin said. “Somebody that, because of a disability, the odds are sometimes not in your favor and the fact he’s been able to progress and get to where he is…it’s just an honor to be a small part of his journey.”

After moving to Jefferson elementary school, Lynch’s learning experience changed in fourth and fifth grade. He benefited from smaller classes but still struggled at times. His frustration mounted. He would act out. During fifth grade, he was suspended for misbehavior in the classroom and spent school time at home.

“I had a very hard time in that sort of setting because I didn’t know what was going on and I was just developing as a kid,” Lynch said.

In sixth grade, Lynch met a principal who would change the course of his academic career and joined a program that would do the same for his social life. Paul Peri, then the principal at Franklin’s middle school, accommodated Lynch’s needs. When Lynch disrupted a classroom, he wasn’t suspended. His parents were notified and Lynch took a step back to think about his behavior.

Franklin High graduate Declan Lynch will be heading right down the road to Dean College in the fall. Art Illman | Daily News staff

Lynch kneels next to a congratulatory sign honoring Franklin High graduates. Art Illman | Daily News staff

That same year, he joined Best Buddies, a nonprofit program that pairs disabled children with one-on-one friends. Lynch said, the program brought him out of his comfort zone. At Best Buddies, Lynch let loose with kids his age. They danced around the gym during their warmup sessions organized to not only incite movement among the group but also uplift their moods with music. Together, they laughed.

Through Best Buddies, Lynch made long-lasting relationships – friends he would hang out with long after their partnership in the program ended. They attended movies, grabbed a meal at Panera Bread and eventually reunited after his various buddies went away for college.

This was all part of Lynch becoming comfortable with himself, understanding that he had different needs and being nervous was OK. He could fight through those things. That’s what Raffin taught him in eighth grade, when the pair discussed the term “grit” at length.

It’s a word commonly explored among students and teachers who combat learning disabilities, Raffin said. A TED Talk presented by Angela Lee Duckworth, which Raffin’s students watched, defines grit as, “passion and perseverance for very long-term goals.”

“The definition is hardworking and determined,” Lynch said. “I can definitely say that I’m hardworking when it comes to work in general. I’m also determined to get my goals done.”

Lynch’s emotional outbursts were a product of him wanting to succeed so badly, Raffin said, not an incapability. He learned with Raffin that he could succeed in academics, it just required different methods. When Lynch reads a book, he also listens to an audio book. The same goes for editing an essay, which he prefers to do alongside an electronic reader. The double sensory input helps him better retain information.

The fears Lynch had about succeeding in the classroom, translated to social anxiety as well. He feared situations such as joining a lunch table full of students, even if asked. He wasn’t sure about playing Unified Sports, an inclusive sports program for Special Olympics athletes. Lynch expected things to be far worse than they ever actually were.

His freshman year, he left a school dance because the number of students in the gym overwhelmed him. While other high school staff who weren’t familiar with Lynch assumed he had left the gym to drink alcohol or cause some other sort of trouble, Peri, then the principal at Franklin High School, knew what was happening. He found Lynch outside distraught. His mother, Katie Lynch came to pick him up.

“”Mom why’d you have to make me this way?” he asked her.

Just like the accommodations for academics, Katie Lynch knew there were ways her son could still enjoy a dance. With the help of Peri, they created a breakout room for students who are overwhelmed by a crowded gym. Students could hang out in the breakout room with a monitor, play a game, then return to the dance when ready. Lynch asked to go to the next dance after that.

When Lynch joined Unified Sports, there were only a few athletes from Franklin. He participated in track and field. After throwing the javelin six feet on his first throw, he won the unified track and field championship with a 36-foot throw by the end of the season. His 28-foot improvement was the best of any athlete participating in the event.

Unified Sports gave Lynch confidence. Girls who had helped support him during Unified Sports, joined his lunch table. He became a board member for Best Buddies, representing students with disabilities at meetings. In March 2018, he represented disabled athletes in Unified Sports at a meeting with the Massachusetts Interscholastic Athletic Association, the state’s high school sports association, to discuss integrating Unified Sports with standard MIAA athletics.

Declan Lynch has his eyes on the ball during a Unified basketball game. Courtesy of Lynch family |

“I feel more comfortable at Franklin High School because of Unified Sports,” Lynch said at the MIAA meeting. “I have a sense of family that I have never had at any other school…I doubt myself a lot because things are hard for me. At the beginning, I didn’t want to play but at the end I felt different.”

Lynch helped grow Franklin’s Unified Sports teams from about three athletes to a basketball team with 15 players and stands full of fans supporting the team, Katie Lynch said. This past winter, Franklin Unified Sports started bocce ball and continues to expand each year with more athletes and supporting students.

Because of COVID-19, the Unified Sports banquet wasn’t held in person, but Raffin still visited Lynch for a social distance gathering in Lynch’s front yard. Her former eighth-grade self-doubter, soon to be a college freshman, had recently received the Mary Doherty Award. The award, granted to any student in the entire high school, is named after a teacher who inspired her students to achieve more than they thought they could.

Five years after their meeting in the eighth grade, Raffin and Lynch laughed over the difference between his aspirations then and what became his high school achievements. They looked over at the driveway where a silver Ford F-150 sat.

Lynch passed his driver’s test during high school and sometimes drove the pickup truck to school. He’s picked up his sister from work and traveled to his own job as well. Next year, he could drive it to Dean. In four more years, who knows where he’ll bring it. He believes he can go anywhere now.

* * * *

Maggie allen

Hopkinton High School

Hopkinton High graduate Maggie Allen ran track at Hopkinton High School. Natham Klima | For MetroWest Daily News

Hopkinton grad Maggie Allen helped foster school spirit

Sarah Ellam wasn’t sure why Maggie Allen was so interested in the school’s pep rally. Sure, it was an exciting event for Hopkinton High School but Allen seemed to have a purpose. Just as she displayed an ability to articulate herself and spark conversation in Ellam’s English class, Allen had stirred up interest for the school event.

“I thought she was just kind of naturally doing this to encourage other people because she wasn’t doing it to be in the spotlight,” Ellam said.

Allen, unbeknownst to Ellam, was a newfound member of the student council. She joined in the fall of 2019 because, “Senior year, why not,” Allen said. She was one of those kind of high school students, one who led by example, sometimes without knowing it. In a class that Hopkinton High School staffers will remember as one of their best, Allen was the glue that helped students from various groups stick together.

A track captain for the Division III indoor state champions, Allen helped instruct online training programs this spring, coordinated music for school dances and initiated student section participation in sports other than the mainstays of football and boys basketball. She’ll attend Middlebury College next fall to study neuroscience with a minor in Spanish while also running track.

Ellam says Allen is just one of those students “I’ll never forget.

“It was clear that she was someone that sent a message to her peers that was a positive one but also unifying them as a group,” Ellam said.

Allen had long been the spark for Hopkinton’s track team. She helped initiate dance sessions with a music playlist that included songs such as Waka Flocka Flame’s “No Hands” or Cascada’s “Everytime We Touch.” She completed a comeback in hurdle relays at state meets more than once. So when COVID-19 ended Hopkinton’s spring season before it started, Allen kept things moving once more.

Maggie Allen poses for a picture with her running shoes and mask outside her Hopkinton home. Nathan Klima | For MetroWest Daily News

Maggie Allen (second from right) laughs while talking with teammates Delaney Mick, Caroline Estella and Schuyler Gooley and track coach Jean Cann during practice in February. The coronavirus pandemic ended their season just a few weeks later. Art Illman | Daily News staff

With the help of other captains and the coaching staff, the track team organized online workouts three times a week. Pre-recorded videos of upperclassmen such as Allen flashed on the screen for underclassmen to learn proper squat or lunge form. On Fridays, Allen organized yoga and Zumba classes for her teammates instructed by her mother and aunt, respectively.

She helped ensure Hopkinton didn’t lose the team atmosphere of spring track and field. The underclassmen needed their first experience of the Hillers’ team camaraderie. With assistance from others on the team, during quarantine Allen organized Sunday Zoom dinners with the team. Instead of a traditional team pasta dinner the night before a meet, Allen showed off fish tacos on the screen while others cooked up their own version of the dish before virtually sharing a meal together.

“If you have one girl who literally has no fear of putting herself out in front of the entire school, then all the other young girls, they’re just going to follow suit,” said Hopkinton track coach Brian Prescott. “I don’t think it’s an accident that we were the state relay champions and Division III champions while Maggie was a senior.”

One of Allen’s projects in the fall was redirecting school spirit, particularly student fan sections, to a more diverse group of sports. She’d played girls’ soccer throughout high school and rarely saw a crowd outside of the final state tournament games. Allen and her fellow seniors changed that by attending many home girls volleyball games. They coordinated outfits for the crowd with whiteouts or camo themes, among others, and brought a boys basketball high school-playoff style atmosphere to the girls volleyball gym.

“That’s awesome especially because it’s a girl sport,” Allen said. “And so many people showed up for a girls sport because even now you don’t see a lot of people showing up to those sporting events all the time.”

Perhaps unknowingly at times, Allen positively influenced the community at Hopkinton. She helped reinstitute school dances, which she contributed a playlist to so the school didn’t need a DJ. Teachers are hopeful her enthusiasm in student sections for all sports will carry into future years. She’s just one of those kids who brings the group along with her. For Hopkinton and Allen, that meant bringing her 2020 classmates through a ride the faculty won’t soon forget.

“I just love the high school,” Allen said. “I’ve had such a great experience with it.”

* * * *

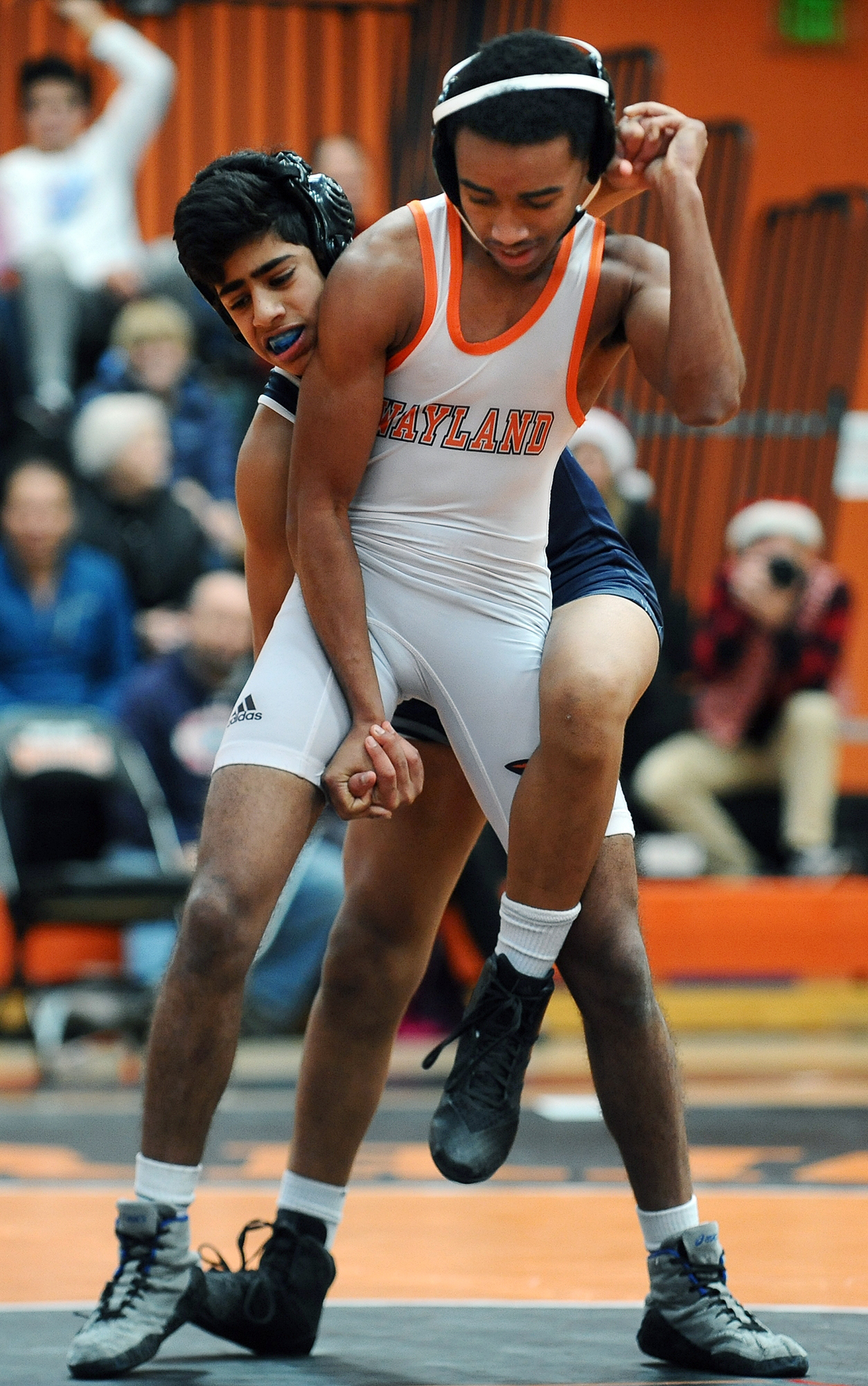

shawn bernier

Wayland High School

Wayland High graduate Shawn Bernier holds a pre-transition photo of himself in a park near his home in Boston. John Walker | Daily News staff

Through Youtube, Wayland senior documents journey to self-acceptance

He decided to try something different this time, because lately Shawn Bernier wondered if his audience should get to know him better. He reached for his notepad filled with 40 facts about himself. He read them aloud with his Panasonic camera rolling.

“What’s going on beautiful people?” he said. “Today I tried to do something a little different.”

Shawn Bernier is 18 years old. He describes his favorite color as a “deep wine” or a “dusty rose.” He prefers Dunkin’ Donuts, because he’s a “proud Bostonian,” but his favorite caffeinated drink is a caramel frappuccino, which comes from Starbucks. His favorite music comes from hip hop artist Kendrick Lamar, followed by pop artists Katy Perry and Adele.

“Who is Shawn Rosiah Bernier outside these transgender walls?” he asked, stretching out each syllable of his name. It was April 26, over a month since Wayland High School closed, 10 months since he was elected student body president and 19 days since his Youtube channel broke 50,000 subscribers.

“So here I am with the delivery of a video,” he continued. “With 40 random facts about me.”

The answer to that question – who is Shawn – depends on whom you ask. He’s the middle school student in the METCO program timid about entering Wayland Public Schools, or the senior student body president who sits with underclassmen to make them feel welcome. A dedicated math student, who asks for extra help, or the dedicated math literacy teacher, who gives extra help. The potential starting running back on the football team until his gender re-affirming surgery – part of his female-to-male gender transition – sidelined his senior season. The senior who joined the wrestling team late, then placed at sectionals months later.

“Even if you don’t teach him you know who he is,” said Eric Wolven, his math teacher of three years and student council adviser. “He’s someone who stands out for the right reasons.”

There’s always gonna be a journey in life where you make decisions that are tough and hard.

It’s rare for the Youtube channel to come up in his conversations, more so for Bernier to initiate the topic. Three of his friends and a mentor said he seldom brings it up, and two mentors had never heard of it. But each video acts as a window into his life, with certain segments containing Buzzfeed quizzes and Netflix recommendations, while in others, Bernier pieces together more intimate moments: grouped in a girls cabin as a preteen, when he felt more like a boy. Coming out to his parents as a transgender male at age 14. Transitioning at 15.

The different environments Bernier traversed has shaped his beliefs, so when the camera rolls, he’s “thinking out loud,” but in a calculated way. There are some times when he’ll delete a recording. A couple times when it’s not polished enough. But in this video he was rolling, animating his life through these 40 different facts.

Fact number 9: He’s 5’3”.

“And if that’s an issue, run away now.”

Fact number 13: He’s fairly religious.

“I have a really strong connection with God and being a Christian man.”

Fact number 14: He has many personalities.

“But I’m very selective with who gets to see what side of Shawn.”

Bernier watched Youtube “religiously” when he was younger, something that helped him identify as a transgender male at 14 and start his physical transition the year after. But still, nobody completely looked like him. He couldn’t fully relate to one specific youtuber.

“I had noticed that there weren’t many transgender people of color, especially out there publicly,” said Bernier. “So I wanted to be, essentially, a trailblazer.”

He makes sure to answer most questions left in the comment section, some that seek advice and some that look to troll. When viewers privately message him looking for advice, he’ll start with a disclaimer, that he’s not a doctor. Then he answers most questions, the ones about his background or his advice, even if he’s explained it before, even if the question makes him cringe.

“Because if I’m not gonna answer it, who is?”

* * * *

Bernier often spends his roughly one-hour commute from Boston to Wayland with his headphones on, watching motivational videos that have quietly shaped his mindset.

Dr. Eric “ET” Thomas , a pastor and CEO, is one of three speakers he said has particular impact. A former high school dropout who later earned a Ph.D. in Education Administration, he makes Bernier think of where he’ll be when he finishes his commute, in a school system he was once timid about entering.

Dr. Adrian Mims, Bernier’s mentor and founder of The Calculus Project, a math program for Boston students, detailed some of the struggles that black students from Boston face when attending suburban schools through METCO. The farther away from Boston, he said, the harder it can be for these students to fit in. Wayland Public Schools is no different, about an hour commute from Boston and a black student population of about 5%.

For Bernier this meant carrying himself differently in the halls of Wayland High School than he would in Boston. It meant switching some of his tendencies — “certain things that are more appropriate in the city to say or do,” he said. In middle school he gravitated toward other METCO students, because that’s where his comfort zone was.

“When we act like a fool on the bus, in school you have to be on your best behavior,” said Bernier. “The last thing you want is for someone to say ‘oh, that METCO student was acting up.’ It looks bad for yourself, your family and your program.”

Gone now are the insecurities of elementary school, when Bernier once told a METCO coordinator “I wish my hair was straight.” Gone is the anxiety in middle school, when he thought embracing the Wayland community meant leaving his Boston one behind.

“(I adopted) this idea of how to integrate into this society,” he said. “And not essentially assimilate to the Wayland population.”

Here’s Bernier now, the student body president, who everyone seems to know and everyone seems to have stories with. But there he was four years ago, reserved from traversing Wayland’s social cliques. He called this comfort a “weird progression” that was potent four years ago, when as a freshman, he considered joining the football team — a sport he hadn’t officially played.

Wayland High graduate Shawn Bernier is heading to Wheaton College in Norton in the fall. John Walker | Daily News staff

Adianez Cabral, a fellow METCO student and close friend since middle school, said that was Bernier’s turning point – when football teammates turned into friends. More friends turned into schoolwide connections. Connections meant higher confidence, a more vocal Bernier, including Sept. 28, 2017, just before Wayland High School’s game against the Boston Latin School.

Bernier, then a sophomore, and two other black teammates kneeled during the national anthem, the Wayland Student Press Network first reported. A poll conducted by the network found that 48.9% of the respondents did not agree with the protest.

Bernier expected that. He knew the student body was divided on the issue. But now a sophomore, in the midst of becoming more vocal, Bernier was speaking up. He was the president of POWER, a club meant to promote difficult discussions about society — discussions that often had split opinions and made people uncomfortable. Discussions like the one he helped start that night: should football players kneel?

The question reverberated through the school weeks later as POWER hosted a discussion about the topic, and promoted it in government, English and history classes throughout the school. Students flooded in during a 30-minute lunch period, and POWER cued up videos from those who agreed with the protest and those who were against it.

“I think he’s found his voice. I think he’s recognized his power, knows that he’s a leader,” said Mims, who had discussed the protest with Bernier. “I think he’s kind of developed a sense of purpose, which I think that? Check quote happens with a lot of very young people as they get older. I think that’s good. I think Shawn wants to figure out how to make his impact and promote change.”

* * * *

Bernier with his MIAA wrestling medal and sitting in a park near his Hyde Park home. John Walker | Daily News staff

During a Dec. 2019 match in the 106-pound class, Bernier takes on Lincoln-Sudbury’s Vehaan Keswani. Art Illman | Daily News staff

Change comes on different scales, and before he promised it to the school during his presidential campaign, Bernier was changing the dynamic of a smaller population, his sophomore year math class.

Emma Kiernan sat next to Bernier for much of the year. The class was small, she said, and Kiernan found herself guiding the social interactions at first. It’s not that Bernier was quiet — he was president of POWER club and spoke up when he needed to. He “was always a likeable guy,” said his teacher — but in that particular class, his day-to-day actions mirrored the rest of her classmates at first. “Stiff and awkward,” said Kiernan, but that started to change.

Wolven, the teacher, started to see a subtle shift when he had Bernier for junior precalculus, then senior statistics. He started raising his hand more.

“It’s just (more) confidence and comfort,” said Wolven. And the next year, at Wolven’s suggestion, Bernier launched a campaign for student body president with C.J. Brown, a football teammate he grew close to in AP Government class.

“He started to get more confident and understand that who he was did impact people well,” Wolven said. “And people did respond to it.”

Soon, they were hiding campaign shirts throughout the school, a scavenger hunt where the winner would be featured on their Instagram page. “Vote for the GOATs.” reads one. “Let us drive the boat,” reads another.

Bernier became known as a people person throughout the school. He grew close with Brown, then with the rest of the student body. He sat at underclassmen tables, urging them to speak up about what they wanted to see in their student government.

“Now senior year, he’ll talk to anybody,” said Kiernan, who serves on the student council alongside Bernier. “Anybody in the hallways.”

“That’s why my music selection is so diverse,” Bernier said.

* * * *

Eighty-five seconds after the whistle blew, the ref took Bernier’s arm and raised it. In a space that felt so unfamiliar, where he was just trying to “go with the flow,” Bernier, by then a senior, had mimicked the technique he learned in practice, pinned his opponent and started his varsity wrestling career at 1-0.

Bernier thought competing for the running back job would be the climax of his football career. Playing under the lights. But his top surgery, part of his gender transition, made it too dangerous to play in the football season, so he spent the fall as the team’s manager, recording statistics and mentoring younger running backs.

Top surgery is a transgender or gender reaffirming procedure that can alter the chest’s size, shape or overall appearance. The recovery time varies, according to Healthline. For some, it can be two to three weeks. For others, it means months. For Bernier, it meant that the very moments he was waiting for – summer workouts, grueling days of practice and playing week after week – could damage his long-term recovery.

In June, months before the football season, Bernier posted a video of himself sitting at the table, hours before the surgery that would end his football career.

It was June 19, 2019, and looking at the camera, Bernier offered advice.

“There’s always gonna be a journey in life where you make decisions that are tough and hard,” he said. “But whether you make those decisions or not, it’s gonna be hard. So you might as well take the harder route to obtain something in life that you want then taking the route that’s gonna be easy.”

Joining the wrestling team was never part of that plan. Neither was placing at sectionals. Neither was school getting canceled weeks later, or finishing high school through a computer screen.

Bernier outlines why he has a plan in a video titled “How to Become Your Best Self.” Your plan should have a “why,” or reason for improving. It should have a “vision,” a notion of where you want to be in five years. Those will make it easier to change your habits, what he called the “engine of your car to use your why and vision as fuel.”

In a year filled with uncertainty, Bernier’s long-term plans remain unchanged. In four years he wants to graduate from Wheaton College, where he’ll start next fall. He wants to expand his Youtube brand, and one day, start a business. Maybe he’ll write a book. Maybe he’ll do all three.

The “why,” the “vision” and the habits that Bernier adopted stem from the motivational videos he listened to each day. They come from finding comfort in uncomfortable situations – becoming more vocal in math class and finding friends because of it. Dividing the school by protesting and bringing it together through conversation. Joining a sport he hardly knew as a senior.

That particular video was made on Dec. 26, 2018, about six months before his top surgery and a year before he joined the wrestling team. Bernier looked at the camera and offered advice he learned from football, the sport he didn’t yet know he wouldn’t play again.

“When you work on any aspect, any element of yourself, by pursuing it one day, for X amount of minutes, you’re allowing yourself to be better than you were the previous day.” he said. “…By day 30, you’re already 30% better. By day 100 you’re 100% better.”

* * * *

tristan beck torres

Holliston High School

Holliston High’s Tristan Beck Torres will be studying at Western Michigan University in the fall. Nathan Klima | For MetroWest Daily News

Music to his ears: Holliston High grad Tristan Beck Torres

Four years of memories came flooding back when senior Tristan Beck Torres stood in the empty band room. Recording music with friends in the lab. Setting up microphones for the jazz band. Helping peers edit their projects.

He downloaded his project files off a lab computer, months before graduation, and packed up equipment to take home for the rest of the school year. And after setting up a makeshift recording studio at home, the Holliston High School senior hasn’t missed a beat.

“Being able to stay home and work on creative stuff has been a silver lining in this situation,” he said.

Beck Torres, 18, found himself in Sean Bilodeau’s music technology class after failing algebra freshman year. Since then, he’s spent every free minute in the music lab, honing his music technology skills that he’ll take to Western Michigan University in the fall.

His music career began in elementary school when he learned to play the clarinet. Beck Torres later learned tenor sax, which he played in the high school jazz and concert bands.

Bilodeau, the band director and music teacher at Holliston High, watched Beck Torres grow as an artist since sixth grade. He remembers when Beck Torres took over the classroom whiteboard to map out songs using musical concepts he learned. His passion for music is infectious, inspiring other students to spend time in the lab, Bilodeau said.

“Every project I assigned, (Beck Torres) was getting more and more excited,” Bilodeau said. “He wanted to learn everything I was doing so he could help, too.”

While the pandemic canceled remaining live performances for Beck Torres and other Holliston High musicians, he tried to make the most of social isolation. The recording and mixing equipment he brought home from school — including a microphone and synthesizer — allowed him to help produce a virtual concert and other passion projects.

Beck Torres has been editing a video performance of “Won’t You Be My Neighbor” featuring the high school community that is expected to be part of Holliston’s graduation ceremony. Students and staff recorded vocal and instrumental parts for a cover of the song, which Beck Torres got the idea for after seeing the trailer for the Mr. Rogers documentary. The project is a good way to bring people together even though they’re separated, he said.

Bilodeau helped Beck Torres and other students bring home instruments and equipment so they could continue their music education during online learning. Teaching and leading rehearsals virtually is tough, Bilodeau said, since the personal connection isn’t there.

“You can’t feed off the room because it’s a screen. It’s like talking to yourself almost,” he said. There are still inside jokes scribbled on the whiteboard in the empty band room, Bilodeau said, because he didn’t have the heart to erase them.

Beck Torres said Bilodeau is like family to him. The two said goodbye after Beck Torres loaded the equipment into his car.

“I started crying and I thanked him,” Beck Torres said. “It sucked that I couldn’t hug him.”

Beck Torres with his music mixing board outside his home in Holliston, June 4, 2020. Nathan Klima | For MetroWest Daily News

Beck Torres in his backyard with his CrossFit t-shirt. Nathan Klima | For MetroWest Daily News

Music plays a role in Beck Torres’s life beyond the classroom. Listening to different genres, like heavy metal and K-pop, while working out has broadened his music taste. While he’d love to work as a studio engineer after college, Beck Torres also dreams of owning his own CrossFit gym. He’s currently a level-one trainer after years of working out at Firewall Fitness, a CrossFit gym founded by two Holliston High graduates.

Beck Torres tries to stay productive however he can while at home. He’s been working on visual art, too, using Adobe Photoshop to design stickers and spray painting an old R2-D2 toy.

Freshman year, Beck Torres drew a picture for Bilodeau that’s still hanging in his office today. Bilodeau said it will stay in his office forever.

* * * *

kathleen mendoza

Milford High School

Milford High’s Kathleen Mendoza poses at her home with her replica of the Gran Jaguar temple in Guatemala. Nathan Klima | For MetroWest Daily News

Milford High’s Kathleen Mendoza pushes herself to excel

Not many students take Advanced Placement physics their sophomore year at Milford High School, but Kathleen Mendoza wanted a challenge.

“I decided to go for it and it was one of the hardest classes I’ve taken, even today through my senior year,” Mendoza said. She’s taken several AP classes throughout high school not only for the credit, but for the satisfaction of pushing herself intellectually.

This semester, Mendoza faced a new challenge: finishing her courses from home during a global pandemic. She would start her day checking assignments on Google Classroom before diving into work at the kitchen table next to her younger sister.

Wrapping up senior year from home was difficult at times, she said, because there’s less structure. While this virtual format was a big adjustment, she thinks this experience will prepare her for having to work at her own pace in college.

Mendoza, 18, plans to study biology on the pre-med track at Boston University in the fall. The challenges facing medical professionals amid the pandemic has motivated Mendoza even more to pursue that career.

“I know it’s a career that will have results and I know that I’ll always be helping someone or working to help someone,” she said.

Mendoza will be continuing her studies in the fall at Boston University. Nathan Klima | For MetroWest Daily

Mendoza at her Milford home. Nathan Klima | For MetroWest Daily

Although she’s excelled across subjects throughout high school, Mendoza enjoyed science and math courses the most. She first wanted to work in the medical field after volunteering at Milford Regional Medical Center. She’d help bring materials back and forth from the lab to the pharmacy, and loved seeing people working in that environment.

For Mendoza, remote learning has shuttered the extracurriculars in which she’s involved. She’s the treasurer of Community Action Requires Everyone, a member of the National Honor Society and French National Honor Society, and an editor for the school newspaper. She also volunteers to teach third- and fourth-graders during Sunday service at church.

“I like the idea of being able to give back, even if it’s in a small way like volunteering once a week at the hospital,” she said. “It’s nice to know how even me, just being one person, I can help my entire community.”

Mendoza balanced school work with extracurriculars throughout high school by setting goals for herself, such as getting a good grade on her next test and getting accepted into her dream college.

Timothy Walsh, a science teacher at Milford High School, said he wishes all of his students were like Mendoza. He’s taught her every year since her sophomore year, including AP Biology and principles of biomedical science.

“She just thinks differently than most kids her age,” Walsh said. “The way she kind of attacks problems.”

Mendoza is eager to understand the material she’s learning beyond just to get a good grade, said Mary Casello, one of Mendoza’s math teachers. When she struggled with a problem in AP statistics, Casello said she never got discouraged. She didn’t let up until she solved it, and then she’d move right on to the next one.

Playing sports throughout high school helped get her mind off schoolwork, Mendoza said. She was on Milford’s soccer and tennis teams, and hopes to continue playing sports for fun after high school.

In her free time at home, Mendoza has been watching “Grey’s Anatomy” and playing video games with her siblings. She was originally set to travel to Iceland for a mission trip this summer, which was postponed to next year because of the pandemic.

One of her favorite places she’s visited during her travels is Guatemala, where her parents are from. Mendoza loved learning more about the culture and getting to know the area where her parents grew up.

Her dad is one of Mendoza’s biggest role models, she said. When her father first came to the United States, he earned multiple degrees to pursue a career in family psychology. Mendoza has striven to work hard and further her education like he has in order to work in a field she loves.

“He worked so hard to pursue what he wanted in life,” Mendoza said. “It really is a big influence (on) me because I want to do the same thing.”

* * * *

molly andrews

Millis High School

Millis High School graduate Molly Andrews. Ken McGagh | MetroWest Daily News staff

Millis High grad Molly Andrews opens a new dimension in the classroom

As the coronavirus pandemic spread in early April, nurses and other health care workers were forced to work long hours wearing protective masks to keep them safe. The practice turned their skin red from irritation and abrasions.

Mary-Ellen D’Espinosa, an eighth-grade teacher at Millis Middle School, knew all about that problem from her sister who works at Tuft Medical Center. D’Espinosa wanted to help and found instructions on how to make a tension relief strap, a small accessory that attaches to the back of protective masks and makes them fit better. But the task required 3D printing technology D’Espinosa wasn’t able to use on her own.

The staff at the Millis public schools hadn’t quite grasped the technology either, but one of D’Espinosa‘s former students had. Molly Andrews, 18, had taught herself the software through online tutorials and trial-and-error. She became Millis High School’s de facto expert on the trend.

She took the ball and ran with it.

Andrews would create the tension straps, hundreds of them, from 3D printers she had spent years teaching herself how to use.

“Here’s the thing,” said D’Espinosa, who is now teaming up with Andrews to distribute the tension straps. “If you make it they will come … Everybody knows a person who’s a doctor, and when (I) contact them they said ‘we’ll take them.’’”

Now, more than a month later, Andrews has made hundreds of tension straps which have been sent across New England. In hospitals across Massachusetts, the straps help frontline workers manage their overextended shifts. When D’Espinosa was contacted by a New Hampshire hospital, she sent them dozens of straps. Five straps went to an employee at Roche Brothers supermarket, who Andrews heard was struggling.

“I just like to think that it’s no trouble, that it helps other people,” said Andrews in late April. “It’s something that I can do while spending minimal time doing because it’s not really that difficult. So why not do it?”

Two 3D printers from Millis High School sit side-by-side in Andrews’ garage, the same ones on which she learned two years ago. Once every hour Andrews walks there from her room, scrolls through the dozens of design files embedded in the printer’s memory and refills the print bed. It’s a routine, taking less than 10 minutes, that’s become easy.

What she leaves at Millis High School is a push to adapt to the new technology in slideshows and tutorials, in the curriculum she helped coordinate, and in a batch of sophomores that now have their interest peaked by the machines — just like Molly did during her sophomore year.

“She took the ball and ran with it,” said David Digiammerino, her former teacher.

Two years ago Andrews had an unusual assignment in her computer science class: using Google Sketch to design her dream house, which to her, was a house in the video game “Super Mario Bros.” By the end of that assignment, she asked her teacher what else she could design.

That year and the next, she searched Youtube for instructions on how to design simple objects, such as how to make a chess piece or how to make a loft between a circular space and a square space. That turned into six-piece, three-dimensional puzzles, and became the precursor to the tension straps.

Digiammerino, a technology teacher at Millis High school, watched as Andrews’ interest grew. He encouraged her to sit in the corner of his classroom near the 3D printers and tweak the machines until she became more comfortable using them. He watched as she taught herself, then taught others and soon, spearheaded a new curriculum that Digiammerino has since adopted.

Millis High School has a new class: 3D CAD Design which Digiammerino said wouldn’t exist without Andrews. Thanks to her work, he said, there’s a growing interest to enroll.

“She’s very self-directed and it was very personalized for her,” Digiammerino said. “It’s funny. I think one of the things that stands out this year (is) she was in a class where there were two or three other students who were interested in 3D printing. She really took over the mentoring of those kids.”

Millis High School senior Molly Andrews.

Earlier this month, Andrews was supposed to return to D’Espinosa’s eighth-grade class to present her senior project. She taught herself Python, a programming software, to build a robot from scratch. She had made a slideshow for the students and documented her programming process. The eighth-graders would have taken turns driving the robot down the halls of Millis Middle School.

But those plans were derailed on April 21, when Andrews’ phone screen flashed with a text from a group chat: Gov. Charlie Baker canceled in-person classes. No prom, no graduation, no senior project reveal. Instead, she made her own video, which D’Espinosa sent to the class.

“Hi everyone, my name is Molly Andrews, I’m a senior at Millis High School, and for my senior project I decided to design, code and build my own Robot, named Razzy,” she said in the video. “And use him as a teaching tool to educate students on robots and robotics.”

Questions flashed on some of her slides. What is a robot? What is robotics? Answers flashed on others, pictures of her design sketches and coding on a few more, and finally, a picture of every item that she 3D printed and didn’t use. Along with it, she posted pictures of Python modules that she initially couldn’t get to work, parts of the project that weren’t visible in the end. She offered students a cautionary message: “Be ready to fail.”

“The students, knowing what Molly did and what Molly accomplished, understand that it’s really ok to fail when you’re learning 3D printing.” said Digiammerino. “I think that’s her biggest legacy, as a model. The student who took the initiative and then jumped in the pool, and did what she wanted to do.”

* * * *

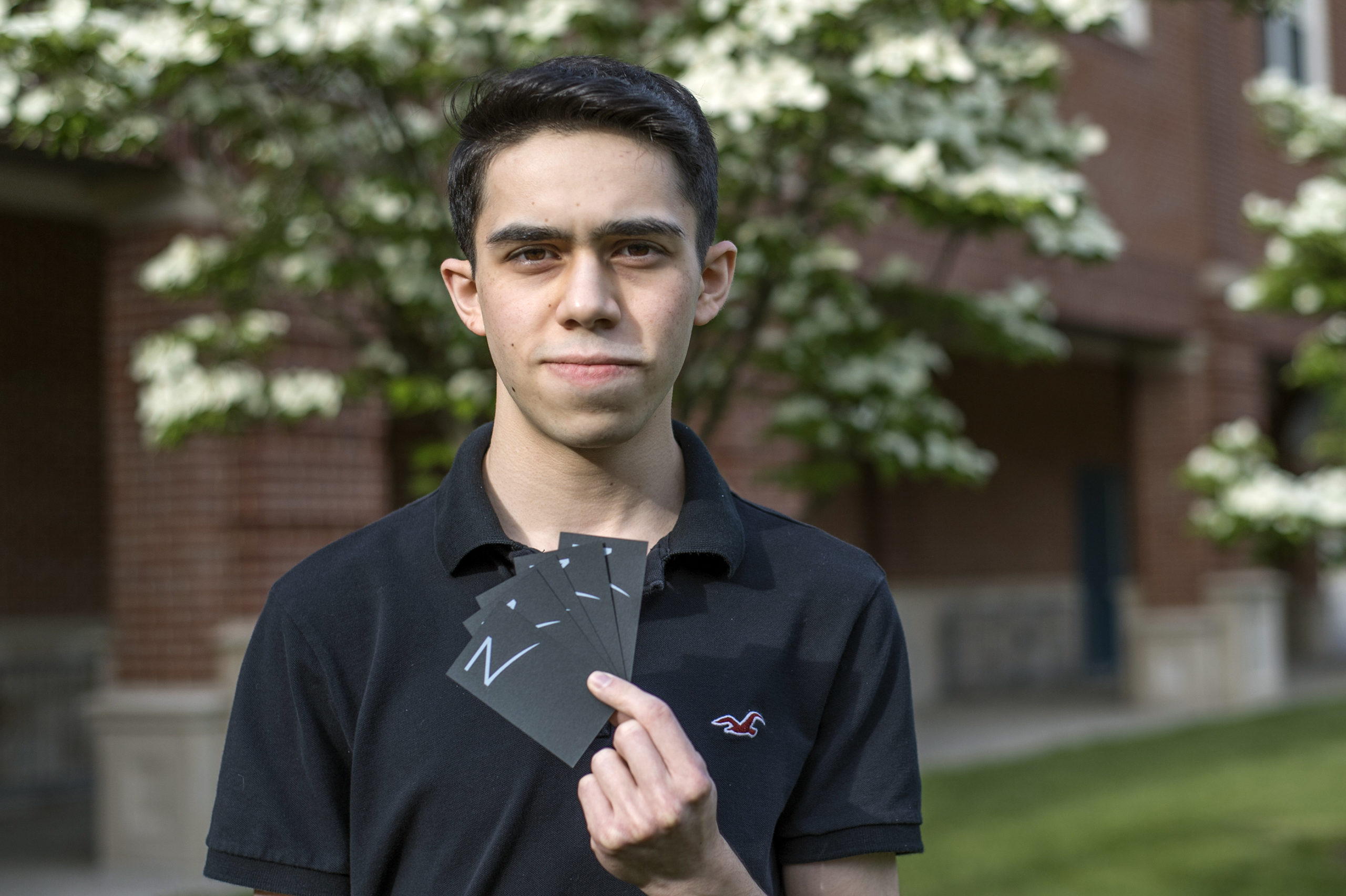

Ethan cardillo

Algonquin Regional High School

Algonquin Regional graduate Ethan Cardillo, of Northborough, with a skateboard he designed. John Walker | MetroWest Daily News Staff

Algonquin Regional’s Ethan Cardillo, the 18-year-old entrepreneur

Ethan Cardillo’s favorite part of the day comes just after 9 a.m. during his four-mile walk on his treadmill. He’ll put on his headphones and let his mind wander, typing ideas into his phone that run through his mind: lyrics from Kanye West or Frank Ocean, a color scheme from a movie he’s drawn to, inspiration for upcoming photoshoots.

“Perfectly comfortable. Pic in bed with flower Crewneck,” he typed one day.

“SUN DONT (sic) SHINE IN THE SHADE,” he typed later.

Some ideas stay on his phone, while others contribute to the projects that fill the rest of his day: a “mockumentary” written by Cardillo and his friends, seniors from Algonquin Regional High School who’ve had their year cut short and a music studio that he hopes to one day create. Or his marquee project, a streetwear-style clothing brand that over the past three years has been built from a start-up project to a brand worn around the world.

“CAPTURE EVERYTHING,” read another note.

A soon-to-be graduate of Algonquin Regional High School, that’s exactly what Cardillo, 18, is aspiring to create: a moment, an idea, something original that conveys who he is. It’s driven his four years at Algonquin and helped pull him out of depression. It’s what he’ll attempt to create in college, as he expands his brand.

“Everybody’s turning to music or shows, any form of entertainment (during quarantine),” Cardillo said. “I think it’s what makes us all human and what differentiates people from everybody else.”

When I needed it most, there was music for me.

An aspiring entertainer and brand designer, Cardillo, of Northborough, started expressing himself through creative works shortly after he learned how to walk. He learned the guitar at age five. He was glued to his computer screen, watching digital Lego animations at age six. He developed an eye for fashion at age 12. He started painting at age 15.

In school he gravitated away from traditional classes and toward projects where he could create something. In his sophomore year geometry class, what snapped his attention wasn’t the area of a polygon or similar triangles, but a phrase that his teacher kept saying to engage the class. A phrase that caught Cardillo’s ear, one that encapsulated what he wanted his brand to be, casual but concise.

“Take note,” his math teacher would say while pointing to the board.

Take Note, now the name of his streetwear-style clothing brand, reflects the skateboarding culture that his cousin exposed him to at age 13, on a below-freezing day at Melican Middle School in Northborough. It was about 18 degrees, Cardillo, who was making photos, remembers, but his cousin, Tyler Nguyen, then 20, was sweating.

“He wanted an action shot, so I had to start trying to flip some tricks around, trying to do a kickflip. It was freezing, and I’m sweating, and he’s like all up in my face trying to get a good shot,” Nguyen said of that day. “So I was in a heat-sweat. I’m cold, but I’m also drenched in sweat. And he’s showing me all the pictures and we’re just trying to get the perfect one.”

Cardillo would head to a skate park where he learned simple tricks like ollies (jumping with the skateboard). The sport itself didn’t stick with him; five years later, he said he hardly skates anymore.

But even after giving up skateboarding, he would watch old skate movies. He was still entranced by what he described as the culture surrounding the sport. The same pull that had his cousin sweating and posing for pictures in sub-freezing temperatures.

“(Skating is) its own form of creativity in my opinion. Because you have to get from point A to point B as creatively as possible,” he said. “You have to be creative on doing tricks, you have to be creative on picking your spot to do your tricks.”

Cardillo’s streetwear-style clothing brand, Take Note, reflects the skateboarding culture that his cousin exposed him to at age 13. John Walker | Daily News staff

In 2017, his sophomore year of high school, Cardillo walked into Algonquin Regional with two tote bags filled with 40 hoodies. He thinks back to those first designs now and scoffs – “I don’t want to look at them,” he said – but back then, like today, those designs were meant to mimic those he found through skating culture, a “casual elegance”.

He went home that day with $1,000, all in $20 bills. He often ran back and forth from a local embroidery company, he said, but soon his network started to expand. He started using online platforms, taking credit cards and doing photoshoots to promote Take Note. Shipments went out to New York, California, and soon Australia, Germany, and Japan, he said.

To make a website, Cardillo became a web designer. To design the clothes he became a graphic designer. To import his product he’s often on the phone with manufacturers in China into the early morning, sometimes until 5 a.m., and oftentimes, that burns him out.

“The more I made, the more I sold, and the more I sold the more people pay attention to it,” he said. “And the more I’ve been able to grow with it.”

Cardillo falls back on the artists he looks up to – Frank Ocean, Kanye West and Wes Anderson, to name a few – to refuel himself when his motivation lacks. Throughout his childhood Cardillo was diagnosed with depression, and in those times, he turned to music and movies to “help put my emotions into tangible things.”

“Self Control” by Frank Ocean helped get him through his first breakup. “MILK” by BROCKHAMPTON, an alternative hip hop group, helped him in “times when I feel like I should be doing better for myself.” The movie “Her” helps Cardillo when he misses old friends and relationships. He takes lyrics from music, or characters from movies, and puts them in the context of his own life. The walls of his house are lined with paintings from his mother, who came to the U.S. from Vietnam, and survived breast cancer while pregnant with his older brother.

Cardillo in the back yard of his Northborough home. John Walker | Daily News staff

Some of the merchandise from Take Note, Cardillo’s company.

Resting in his laptop is Cardillo’s inspiration folder, filled with still frames that caught his eye. The painting of a green ball with the word “motivation” written on it. A picture of a man on fire in an otherwise ordinary living room, a scene from the movie “Hereditary,” “one of the first movies that made me feel super super anxious and uncomfortable while watching it.”

These are scenes, moments and lyrics that Cardillo hopes to one day create, the reason why his cousin posed for photos in sub-freezing weather. The reason why Cardillo walked into school with 40 hoodies sophomore year. The reason why he finds solace in his quiet morning walks, looking for the next creative idea.

“When I needed it most, there was music for me,” he said. “Or there were movies to watch,” he said. ”There was always something, and I think my end goal is to really give that back to people.”

* * * *

blake dresser

Bellingham High School

Blake Dresser, a graduating senior at Bellingham High School, poses for a portrait with his French horn outside his home in Bellingham, June 4, 2020. Nathan Klima | For MetroWest Daily News

Amid uncertainty, Bellingham senior approaches pandemic with resilience

Blake Dresser was in kindergarten when he first heard the French horn. He was in the restroom during an annual senior citizen Christmas concert when a member of the band started playing the instrument.

The sound was unfamiliar to him so on his way back to the concert he asked his teacher what it was.

“She told me it sounded like the horn. So I went back into the cafeteria and I just watched that person play the French horn,” Dresser said. “Ever since, I wanted to play it.”

His first lesson was in sixth grade and six years later, Dresser, 18, planned to perform with the school’s concert band at his graduation from Bellingham High School. But as the coronavirus pandemic swept across the country, large gatherings and ceremonies were canceled, giving high school seniors an anticlimactic end of the school year – and an uncertain future.

Despite the disappointment, Dresser’s resilience gives him the skills he needs to endure constant change. Through family ups and downs and transitioning gender, he is no stranger to adversity.

When he was 6 years old, Dresser’s parents divorced. For a long time, he felt their split was his fault. He coped with this feeling of guilt by keeping a journal.

“I was like, ‘Oh, I’m clearly doing something wrong,’” he said. “But as I got older, I realized too late that they just weren’t working out and I had nothing to do with it.”

When Dresser was 14, his mother moved to Florida, letting him decide where he wanted to live. He chose to stay with his dad in Massachusetts. A few years later, as he realized what a huge decision it was to choose between his parents at such a young age, he felt angry.

To calm his anger, Dresser turned to self reflection. He would write, use silly putty and do deep breathing exercises to work through his hostile feelings.

“I would just sit there and I would reflect on what was happening, what I could do about it, and what I should try,” he said.

I really want to help kids turn their lives around before they’re stuck in the system forever.

In middle school, Dresser was diagnosed with depression. Though he struggled, this is when he first developed an interest in psychology and grew passionate about helping others. That point in his life influenced his academic study, he said. Dresser plans to major in psychology at Bridgewater State University in the fall.

Though Dresser originally wanted to be a counselor for students, he became interested in the criminal justice system at age 12 and now hopes to become a juvenile corrections counselor. His interest stems from his stepfather, a corrections officer at the Suffolk County Jail before moving to Florida, who would tell him stories about his work and bring home prison Bibles.

“I got really interested in the prison system and how things run there, and I knew I wanted to work with kids,” Dresser said. “I really want to help kids turn their lives around before they’re stuck in the system forever.”

Another point of adversity Dresser has faced is his gender transition. As a transgender man and gives himself testosterone shots. But recently he has had trouble getting the specific needle he needs to inject it. Because of the pandemic, he must communicate with this doctor through an online portal, which has been a struggle because he received no guidance in how to use it.

He worries he will not be able to communicate with his doctor to find out if he should change his testosterone dose.

When he first came out as transgender, he received negative reactions from friends. One of his closest friends refused to use his preferred pronouns, he said. But Dresser said he has learned to “embrace (himself) through the negativity.”

Dresser’s mortarboard pays tribute to an Avril Lavigne song. Nathan Klima | For MetroWest Daily News

Dresser is heading to Bridgewater State University in the fall. Nathan Klima | For MetroWest Daily News

He is the president of the Coexist Group at Bellingham High School, an LGBT+ interest group that promotes acceptance. Through this group, he has had the chance to meet many other LGBT+ students and advocate for the community.

“I used the negatives to help myself push through everything and be an advocate for myself and other trans kids that are going through the same thing,” he said.

Coexist Group and other LGBT+ groups have given Dresser a chance to be comfortable in environments he’s “normally not comfortable in,” he said. He cited examples of a Halloween dance at Natick High School and a breakfast at Medfield High School for LGBT+ groups.

Jamie Stacy, Dresser’s adjustment counselor at Bellingham High School, said students, teachers and administrators recognize him as a leader. Stacy has seen Dresser grow “compassionate and resilient” in the five years she has known him.

“What stands out the most about Blake is his perseverance,” Stacy said. “He has sustained many challenges, particularly during his high school experience, and yet he was still able to commit to his health and well-being.”

Though Dresser has had to miss opportunities due to the pandemic, such as performing at Fenway Park with his school’s band and finishing out the year as the Coexist president, he plans to continue his extracurriculars in college.